Executions during the Irish Civil War

By John Dorney

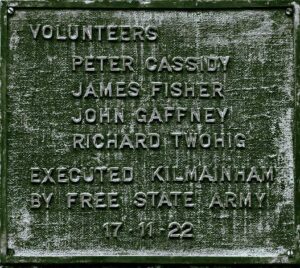

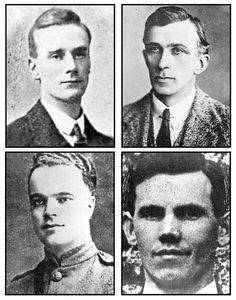

On the morning of November 17 1922, the mother of John Gaffney, an anti-Treaty IRA member and 21 year old electrician at Dublin Corporation, was preparing a food parcel for her son. He had been arrested by National Army troops three weeks earlier, carrying a revolver, and was held in Kilmainham Gaol. She had set out to post her parcel when she saw a ‘Stop Press’ newspaper notice in the streets. [1]

Her son had been executed by firing squad, along with three other young men – the first to be judicially executed in the Irish Civil War. Before the war’s end, 81 men in total would face the firing squads.

Public Safety?

The executions were made possible by legislation known as the Public Safety Bill, which was passed in the Dail on September 27, 1922. The emergency legislation gave to the National Army powers of punishment for anyone ‘taking part in or aiding and abetting attacks on the National Forces’, having possession of arms or explosives ‘without the proper authority’ or disobeying an Army General Order.

Military Courts could impose the sentence of death, imprisonment or penal servitude on those found to be guilty of such offences.

The Provisional Government, which was in place only to enact the Treaty and oversee the handover from the British administration to the Irish Free State, technically had no legal right to enact new legislation without assent of the Governor General, but this post had yet to be filled. Indeed, the Free State itself did not formally exist until December 7, 1922.

So, the Public Safety Bill was technically not a law but simply a resolution passed in the Dáil. It was not until August 1923 that the Free State would pass an Act of Indemnity for all actions committed during the Civil War and also passed new, formal legislation that it would retrospectively legalise what it had enacted in 1922. [2]

The Provisional Government in July of 1922 had closed down the Dail Courts when anti-Treaty prisoners appealed to them for release under Habeas Corpus (the right not to be detained without trial) and arrested the Courts’ Supreme Justice Dermot Crowley.

After authorising executions however, the Government also considered closing down the High Court of the Free State in November 1922, when the legal team of Erskine Childers who was under sentence of death, appealed to it. They argued that the military tribunals that had sentenced Childers to death had no authority over civilians. In the event, however, the Court ruled that suprema lex salus populi – ‘the supreme law is the safety of the public’, which amounted to saying that anything the government did to win the Civil War was legitimate. [3]

Those executed were typically only told on the morning of the execution. The families of the executed men were told afterwards and the bodies were initially not given over for burial but buried in the barracks and gaols where they were shot. [4]

Condemned prisoners were given the opportunity to see a priest or cleric of their own religion. Though most were Catholic, Erskine Childers for example was attended to in his last hours by the Protestant Archbishop of Dublin. They were also allowed to write a last letter to their relatives, the collections of which which form a heart-breaking archive of their last thoughts and wishes.

Why executions?

Why did the pro-Treaty Provisional government embark on such a radical policy? One reason was that it legalised what Government forces were doing anyway. Infuriated by ongoing guerrilla warfare, National Army troops had already been taking out ‘unofficial reprisals’ on anti-Treaty fighters or ‘Irregulars’ – 41 prisoners had already been killed by November 17 according to Republican figures.

National Army commanders Emmett Dalton and Eoin O’Duffy had already issued proclamations (albeit hurriedly rescinded by the Government) to the effect that prisoners caught carrying arms would be shot.

Indeed, Dalton had already executed one National Army soldier for handing over arms to the enemy by that time.[5]

A deeper reason, though, was that the Government thought that radical action was needed to end the war before it bankrupted the new Irish state. Anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch had by this time, explicitly switched from a tactic of large-scale military confrontation to instead concentrating on destroying the infrastructure of government by targeting income tax offices, road and rail lines and government buildings. This was very difficult for Government forces to counteract and the executions were intended as a means of terrorising the anti-Treatyites into calling off their campaign.

The first executions, of four young anti-Treaty fighters in Dublin on November 17, were followed up the shooting by firing squad of leading anti-Treatyite Erskine Childers on November 24. Another three anti-Treaty IRA prisoners were executed six days later at Dublin’s Beggar’s Bush.

Childers, the erstwhile head of Republican propaganda, who had acted also as Secretary in the negotiations with the British in 1921 which led to the Treaty, was unusual in being a senior republican who was singled out for execution. Others, with a ‘record’ in the independence struggle were often spared due, perhaps, to their connections with former comrades on the other side. Ernie O’Malley, for instance, was captured just five days before Childers on November 5 1922 and unlike Childers had actually shot several soldiers, killing one, in the gun battle that surrounded his capture. Yet, despite rumours to the contrary, he was never selected for execution.

Most of those shot by firing squad were young, low ranking anti-Treaty IRA volunteers, though seven were deserters from the National Army and several were apparently not members of any armed organisation. Anti-Treaty women in Cumman na mBan were a central part of the guerrilla campaign and were imprisoned in considerable numbers, but none were sentenced to death. For all of the invective against anti-Treaty women on the government side, judicially shooting a woman would have been breaking too strong a taboo for Irish society at that time.

Reprisals

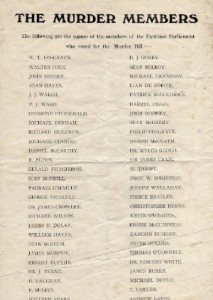

The IRA Chief of Staff, Liam Lynch responded to the execution policy with a chilling series of orders to IRA units to kill in reprisal any TDs who had voted for the ‘Murder Bill’. National Army officers were also to be killed if they served on military courts, he ordered and the houses of TDs, Senators and pro-Treaty supporters were to be burned down.

On December 7 1922, Lynch’s orders were acted upon. Members of the anti-Treaty IRA Dublin Active Service Unit ambushed TDs Sean Hales and Padraig O Maille on Dublin’s Ormonde Quay, shooting both but killing Hales.

Targeting TDs could conceivably have caused a collapse in pro-Treaty morale and triggered a flood of resignations of pro-Treaty TDs. The Government needed to swing the balance of terror again its favour. The following day they resolved that four leading anti-Treatyites – Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Joe McKelvey and Dick Barret would be shot in reprisal for Hales’ killing.

The first three had been leaders of the IRA Executive whose seizure of the Four Courts in April 1922 ultimately triggered Civil War. Barret, from Cork, was probably selected for his role in prison riot at Mountjoy Gaol in which three soldiers were killed.

There was no attempt at legality on the Government’s part. The four were never charged with any offence nor brought before a military court. It was a reprisal pure and simple.

The four prisoners in Mountjoy were simply given a blunt statement:

“You ________ are hereby notified that, being a person taken in arms against the government, you will be executed as a reprisal for the assassination of Brigadier Sean Hales TD in Dublin on December 7th, on his way to a meeting of Dail Eireann and as a solemn warning to those associated with you who are engaged in a conspiracy of assassination against the representatives of the Irish people”.[6]

‘Local Executions’ and Military Committees

Minister Kevin O’Higgins, whose friend Rory O’Connor was among those executed on December 8, was nevertheless one of the most hawkish advocates of execution. He subsequently argued that executions should be extended from Dublin to every county in order to increase the psychological pressure on the ‘Irregulars’ to surrender.

To ‘vindicate the idea of ordered government’, he argued, there ‘should be executions in every county. The psychological effect of executions in Dublin are very slight in places like Wexford, Galway and Waterford…I believe local executions will considerably shorten the struggle’. The object, according to O’Higgins, was not only to intimidate the ‘active Irregular’ or anti-Treaty guerrilla, but also the ‘passive Irregular’ who was not paying taxes, rates or debts.[7]

Accordingly, 69 more official executions were carried out in 1923, with 34 in January alone, in locations from Kildare to Dundalk to Roscrea, Carlow, Birr and Portlaoise, Limerick, Tralee, and Athlone. Only one execution took place in February, in which month an amnesty was temporarily called during which republicans could come in and surrender. But before the end of the war, the firing squads would also be active in Mullingar, Cork, Kerry, Tuam and Ennis.

Additionally, in early 1923, even military trials were, for the most part, dispensed with. Now death sentences could be handed down by ‘military committees’ consisting of National Army officers in the localities, where the ‘factual basis’ of the case was ‘not in doubt’. This judgement was at the discretion of army lawyers. Moreover, possession of weapons could now be inferred if arms were found near where the suspect was arrested.[8]

This essentially eliminated due process for prisoners.

For instance, in County Kerry on 19 January 1923, National Army commander there, Paddy O’Daly, radioed Dublin asking for permission to try and execute three ‘exceptionally bad cases’ after a train line was blown up near Tralee, killing two railway workers.

‘Will you’, he asked, ‘sanction the death sentence… ‘feeling [sic] very strong here for immediate action’. He received a message back almost directly authorising execution the following morning at 8 a.m. There seems to have been no real judicial process at all for those condemned to death, who were duly shot.[9]

An effective policy?

Did the executions help to end the Civil War? Perhaps, but arguably the anti-Treaty campaign fell apart more from the constant attrition of arrests than the effects of the executions.

Certainly however, with another 400 men among the 12,000 prisoners sentenced to death, the anti-Treaty IRA knew that prolonging their campaign further would inevitably result in dozens or even hundreds more executions of their imprisoned fighters.

In Donegal, four anti-Treatyites including a commandant, Charlie Daly, were held at Drumboe Castle, effectively as hostages to prevent future guerrilla attacks on pro-Treaty troops. When on March 11, 1923, a National Army captain Bernard Cannon was killed in an attack in Creeslough Post, the four were executed by firing squad on March 14.

Subsequently a leading Donegal republican Peadar O’Donnell was moved from imprisonment in Dublin to his native county, with a death sentence hanging over his head should the National Army take further casualties there.[10]

The most notable of those who surrendered was IRA Divisional commander Liam Deasy, who after having been captured in February 1923 avoided execution by calling on the men under his command to surrender.

Similarly, in south Dublin, after the capture of an anti-Treaty column in Dalkey in March 1923, the column leader Paddy Darcy reported that, ‘in order to try to save the lives of Meaghan, Neary and Thomas, from execution, Paddy Darcy, OC 1 and 2 Battalions Dublin 2 Brigade IRA surrendered 3 men of G Company with arms’.[11]

A spiral into vendetta

If the efficacy of the executions can be debated, what is certainly true is that the executions helped deepen the spiral of the Civil War into a bitter personal vendetta. Although no more TDs were killed after Sean Hales, a number of pro-Treaty politicians – such as Seamus Dwyer in Dublin – were assassinated as were a number of unarmed National Army officers.

There was also a concerted campaign of house-burning directed against pro-Treaty supporters, politicians, soldiers, former unionists and the landed gentry.

The executions could also lead to vicious local reprisals. In County Wexford, for example, on March 13 1923, three IRA prisoners, erstwhile members of Bob Lambert’s IRA column, were executed by firing squad in Wexford town.

Eleven days afterwards on March 24 1923 at Adamstown, four Free State soldiers happened upon the IRA at McCabe’s pub. One soldier was shot and wounded when he raised his gun. The three others were taken away by the IRA and executed in revenge for the executions in Wexford town.[12]

Pro-Treaty forces in the field continued carrying out ‘unofficial’ reprisals, until the end of the war notably in Kerry where in March 1923 at least 20 prisoners were killed, many, including eight at Ballyseedy, blown up with landmines in reprisal for the deaths of five National Army soldiers in a booby trap bomb. These were only the most infamous of the summary or roadside executions. Various estimates put the total at between 133 and 153 such killings of anti-Treatyites. [13]

Historians of the National Army found a maximum of 53, pro-Treaty soldiers killed when unarmed or prisoners.[14] However, it is worth noting National Army casualties in combat were significantly higher than those of the IRA guerrillas. Executions, both official and ‘unofficial’, were seen on their side as ‘evening the score’.

This bitterness contributed to a particularly hard-hearted character to some of the last executions, in which prisoners who indicated a preparedness to cooperate with the military after capture were executed anyway.

For instance, in County Meath in early March 1923, IRA column leaders, Grealey and Burke (who gave a false name of Keegan) were captured after an armed robbery at Oldcastle, signed an amnesty offer calling on all thirty men under their command to surrender and hand in their arms.

They were, they said ‘sick of this terrible campaign’ and ‘wanted to return to civil life unmolested’.[15] They were nevertheless shot by firing squad in Mullingar.[16]

Similarly, in County Kerry, there was the case of an Englishman named Reginald Hathaway, who had deserted both the British Army and the National Army before joining the IRA. He was captured in April 1923 after an anti-Treaty column was trapped and destroyed (either killed or captured) at Clashmeacon caves; an action in which two pro-Treaty soldiers were also killed. Hathaway was recorded by the Army to have agreed to cooperate, pointing out to them three hidden republican arms dumps.[17] He was nevertheless executed with two other prisoners at Tralee Gaol on April 25.[18]

The miserable cycle of outrage, execution and reprisal was only brought to an end after the death of anti-Treaty IRA leader Liam Lynch on April 10 1923 and the orders of his successor Frank Aiken to first cease fire on April 30 and ‘dump arms’ on May 24.

Aftermath

The bodies of the executed were not handed back to families until mid–1924. Ugly scenes accompanied the handover of the remains of the executed to their families, as military displays and discharges of weapons at the re-interments were banned. The re-burials of the bodies were heavily policed, and in Dundalk shots were exchanged in the graveyard.[19]

The pro-Treaty government remained unapologetic about their executions policy during the Civil War, maintaining that they had simply done what was necessary to save the new Irish state.

Minister Ernest Blythe for instance told an election rally in 1923:

The people in a manner blame the government for the executions but it must be remembered that they were up against guerrilla warfare… It became absolutely necessary for the government to show the fellow with the gun that he could not go out to shoot and burn with only the risk of being taken to prison… Any fellow who went out with the gun and petrol tin deserved the firing squad and none got it except who deserved it.[20]

Kevin O’Higgins responded to heckling at later election of the ‘77’ who were executed by asserting that he would execute ‘777 more if necessary’.[21]

The latter figure of 77 was popularised by republican historian Dorothy Macardle and indeed a later book published as a tribute to those executed is titled ‘Seventy Seven of My Own said Ireland’. In fact, though, this underestimates the total shot by firing squad by the Free State in 1922-23. The true total was 81, rising to 83 if one includes who were shot before the Dail resolution of September 1922.[22] Oddly, the IRA refused to claim some of its members who had been executed for armed robbery while endorsing as its martyrs others similarly executed, even two who had been expelled from the organisation.

In any case, the total of 81 executions was more than twice as many republicans as the British had executed between 1916 and 1921.

Our understanding of the executions in the Civil War period will forever be limited by the ‘Destruction Order’ of 1932. The Cumann na nGaedheal Minister for Defence Desmond Fitzgerald ordered Army Intelligence to ‘destroy by fire’, all Intelligence reports, Secret Service Vouchers and Military Court Records which ‘contain information that may lead to loss of life’, before the Department of Defence was handed over to their Civil War foes of Fianna Fáil. [23]

Even 100 years on, the executions of 1922-23, along with the Civil War itself, remain a scar on Irish political memory. The highly debatable legal processes used complicates the idea that the pro-Treaty government defended democracy and the rule of law. For this reason, it remains, perhaps, the most fraught event to be commemorated during the centenary of the Irish revolution.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please consider contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] MA/ie/CW/Capt Nat Army Captured documents Lott 128, ‘Irregular Publicity’.

[2] Breen, Timothy Murphy, PhD Thesis, The Government’s Execution Policy during the Irish Civil War, 1922-23, Maynooth, 2010

[3] Sean Enright, The Irish Civil War, Law, Execution and Atrocity, p.36-41

[4] Cabinet Minutes November 18-22 1922 Mulcahy Papers P7/B/245.

[5] He was Pte John Winsley of Cork, executed in early September 1922, James Langton, Forgotten Fallen, National Army soldiers killed in action during the Irish Civil War. P346

[6] Maryann Gialanella Valiulis, Portrait of a Revolutionary, General Richard Mulcahy and the founding of the Irish Free State, p.181

[7] Included in O’Higgins testimony to Army Inquiry 1924, Mulcahy Papers P7/C/21.

[8] Enright Irish Civil War Execution, p.57-58

[9] Military Archives, Radio Reports to GHW CW/OPS/01/02/06

[10] See Kieran Glennon’s Article on the ‘Drumboe martyrs’ on the Irish Story.

[11] See John Dorney, ‘The Dalkey Column’ The Irish Story.

[12] Seamus MacSuain, County Wexford’s Civil War p. 88. They were Lt Thomas Jones, Sgt O’Gorman, Sgt Patrick Horan

[13] Andrews, Todd, Dublin Made Me, p.269, The 133 figures comes from a recent count by the Trasna na Tire group.

[14] James Langton, Forgotten Fallen, p.9

[15] National Army Prisoner files MA CW/P/02/02/02.

[16] Sean Enright, The Irish Civil War, Law, Execution and Atrocity, p.94

[17] National Army Operations Reports, Kerry, Military Archives CW/OPS/08/13.

[18] Ibid. CW/OPS/08/08

[19] Dundalk Democrat, October 18 1924

[20] Anglo Celt, August 4, 1923

[21] Cited for instance in Martin Breathnach, (2002), 70 years of Fianna Fail, p.20

[22] Enright, Irish Civil War, Executions, p.120

[23] Military Archives, CD 334 Destruction Order 7 March 1932.