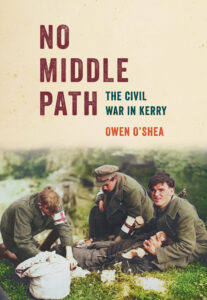

Book Review: No Middle Path: The Civil War in Kerry

by Owen O’Shea

by Owen O’Shea

Merrion Press, Newbridge 2022.

ISBN97817835374333

Reviewer: Thomas Earls Fitzgerald

In the summer of 1922 Free State army commanders Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy devised a sea borne offensive operation to effectively re-conquer the vast swathes of the country still under anti-Treaty control. Troops were landed at Cork city, ports on the Connacht seaboard and at Fenit the port of Tralee.

The troops charged with the reconquest of Kerry were spearheaded by the Dublin Guard, largely officered by pro-Treaty elements of the Dublin IRA, under the command of Paddy O’Daly the leader of Michael Collins’s deadly assassination Squad between 1919-21. O’Daly later was joined by David Nelligan who had acted as Collins’ inside man in Dublin Castle.

O’Daly and Nelligan, were men without formal military training, but ingrained with the knowledge that survival was crucial in guerrilla conflict and that this survival depended on the effective use of terror. O’Daly and Nelligan knew that it was necessary to terrorise the crown forces into fearing the consequences of any retaliatory action, and thus allowing the IRA to continue to operate. The officers of the Dublin Guard operated in Kerry in the Civil War with the mentality that it was kill or be killed: an attitude formed on the streets of Dublin between 1919-21.

Accordingly, when a party of Free State troops were lured to their violent deaths by a trap mine at Knocknagoshel, Nelligan and O’Daly’s response had a chilling and frightening logic rooted in this survival instinct.

The Civil War in Kerry will always be associated with the atrocities of March 1923.

The policy of strapping republican prisoners to mines that were then detonated at Ballyseedy, Countess Bridge and Cahercivieen was effectively intended as a deterrent message to the anti-Treaty IRA of the cost that would incur if they continued to use mines against Free State troops. Despite the subsequent denials and cover ups Nelligan and O’Daly were well aware that the anti-Treaty IRA knew exactly what happened at Ballyseedy – they wanted them to know but remember too.

Indeed, many acts of escalatory violence between 1918-1923, whether by the crown forces, the IRA or Free State army, were inspired by this desire to demoralise and frighten opponents into not taking retaliatory action. Often this policy failed.

In 1920-21 the IRA became more aggressive and willing to take lethal action in direct response to the Black and Tans policy of unofficial reprisals – in effect the Black and Tans had achieved the opposite of what they had sought to achieve by fermenting rather than crippling armed insurrection. In 1923, it arguably worked as the anti-Treaty IRA in the county did not again lure their opponents to hidden trap mines.

In 1922-23 the policy of executions by the Free State and atrocities like at Ballyseedy may have crippled the anti-Treaty’s IRA desire to continue fighting but their insidious legacy proved more damaging in the long run. Richard Mulcahy, by convincing his cabinet colleagues, in the Autumn of 1922 to implement an execution policy of republican prisoners, was also demonstrating that ‘kill or be killed’ and survival instinct, like that of his field commanders, which he learned as Chief of Staff of the IRA between 1919-21.

However, Mulcahy, like O’Daly and Neligan, was blind to the larger consequences of these acts. In Kerry, the good will felt towards the Free State evaporated as people with no sympathy for the anti-Treaty side were repulsed to hear of men blown up mines, prisoners brutally tortured and the drunken machismo and trigger-happy culture that came to define the officers of the Free State army in Kerry. Indeed, as O’Shea notes in No Middle Path a number of Free State soldiers resigned from the army in disgust at the actions of their compatriots. But more importantly Kerry’s experience of Civil War became synonymous with Free State brutality, leaving a particularly lasting legacy.

Kerry: A County Apart

In most histories that deal with Ireland’s civil war of 1922-23, at a certain point after the seemingly crucial summer months of 1922 are addressed , it seems customary for the author to write some variant of the following: the war settled down into something that was not really a war, in the traditional sense, but rather made up of acts sabotage, low-level violence and retaliatory executions.

This was the rule across the country with the exceptions of Kerry, which proved to be a hotbed of violence, and to a lesser extent, counties such as Cork, Tipperary, Mayo, Wexford and Sligo. The latter two, like Kerry saw far more bloodshed in the Civil War than before the Truce of 1921.

Kerry accordingly, casts a long shadow in any analysis or understanding of the Civil War.

Owen O’Shea’s new volume is the first expertly researched and written history of Kerry’s experience of southern Ireland’s fratricidal conflict.

Nonetheless, for all the recent research on the Civil War Owen O’Shea’s new volume is the first expertly researched and written history of Kerry’s experience of southern Ireland’s fratricidal conflict. Historians such as Gavin Foster and Gemma Clark have respectively looked at factors such as social issues and arson that helped inform the conflict, but O’Shea’s volume is the first micro study of the one county most badly affected by the violence of Civil War, Indeed, Kerry’s whole revolutionary experience is largely defined and sadly made notorious by its experience of Civil War.

That is not to say that Kerry’s Civil War experience has not been addressed elsewhere by historians such as Tom Doyle and Tim Horgan. However, O’Shea’s study is the first to fully utilise the newly made available Military Service Pensions files from the Military Archives, together with the often-overlooked appeals from compensation civilians made to the Free State government available in the National Archives.

O’Shea’s scope is also broad, as this is no mere military history or chronology of violent events but rather a broader look at the social impact of the conflict on communities across Kerry, the brutal and callous treatment of women, and the messy and often sad legacy of the conflict on Kerry’s political scene. It also addresses the seemingly never-ending tragic saga of veterans and their relatives attempting to seek some type of financial compensation from both Cumann na nGaedheal and then Fianna Fail governments. O’Shea interestingly notes that some politicians were still dealing with appeals for compensation up until the 1980s.

The great strength of this book is in the tone of impartiality it adopts. Historians, and other commentators, of a pro-Treaty approach will talk of the Free State army being tasked with having to put down an illegitimate, anti-majoritarian militarist revolt in 1922-23.

But such historians and commentators may find it difficult to defend or rationalise the brutal atrocities committed by Free State troops at Ballyseedy, Countes Bridge, Caherciveen and the Clashmealcon caves in the final stages of the conflict in 1923.

Owen O’Shea notes that such acts cannot attributed to a few bad apples in the Free State army’s Kerry Command. Instead O’Shea calmly and dispassionately documents a brutal culture existing within the Free State army in Kerry of drunkenness, vicious and sadistic torture conducted by trigger happy thugs who considered themselves above the law. This conduct, was O’Shea notes, driven more by the officers of the Kerry Command, rather than by enlisted men.

The brutality of the Free State army (or officer class) in Kerry acts a delicious and intoxicating sustenance for historians and commentators of an anti-Treaty position who use these acts as unimpeachable evidence of the neo-colonial, brutal and illegitimate nature of the Free State. But again, here we return to the excellent tone of O’Shea’s writing. The book is often a harrowing journey through the brutality of the Free State forces in Kerry but at no point does O’Shea let the anti-Treaty side off the hook or bestow them with a unique and benevolent patriotism or as somehow being more virtuous than their Free State opponents.

O’Shea expertly documents the intimidation, brutal violence, destruction and looting of property civilians constantly faced in Kerry at the hands of the anti-Treaty (and as my own study, Combatants and Civilians in Revolutionary Ireland has highlighted, this was an endemic element of IRA’s campaign in Kerry from 1918 up until 1923). This intimidation persisted beyond the closure of the Civil War as in some cases individuals and their families continued to be harassed and boycotted by republicans up until 1926.

Not only this but he also addresses the militarist and dangerous rhetoric of anti-Treaty leaders which gloried in death and destruction, thus adeptly showing that neither side in Kerry had a monopoly of virtue, and how the defenders of both sides 100 years on need to recognise the validity of criticism of both the pro and anti – Treaty positions.

A democratic deficit?

O’Shea interestingly notes that it was in 1910 that Kerry last had a truly democratic contest as in the 1918, 1921 and in the 1922 elections Kerry Sinn Fein candidates were elected unopposed – with Labour, the Farmers party and other independents stepping aside in favour of national unity. Kerry arguably never had a say on the treaty as an equal number of pro and anti-Treaty candidates were elected in 1922 unopposed.

Nonetheless, elsewhere the labour movement, had organised successful strikes in opposition to the growing militarism espoused by the anti-Treaty and pro-Treaty factions, thus highlighting the need to address the crippling poverty facing Ireland rather than squabble over the exact nature of southern independence. Indeed, the success of the Labour Party, and other pro-Treaty groups such as the Farmers’ Party in the 1922 election, in constituencies outside of Kerry, is testament to the desire of many people to restore stability and peace to the country, and move beyond the national question.

It also highlighted a desire for parliamentarians to represent their constituents and the issues they faced (whether the need for a parliamentary voice for unionised workers in the form of the Labour Party or voice for agricultural issues in the form of the farmers party) rather than a politics defined largely by bickering over national and constitutional issues.

The past two years of violence by the Crown forces had left much of the country, particularly in hard hit areas like Kerry, on its knees economically with businesses, homes, creameries and farms left in ruins. In the early days of 1922, the IRA in much of the country took over barracks and other large buildings and became the only force seemingly in a position to dispense law and order.

However, unlike in 1920 when the IRA did act as the benevolent, if somewhat priggish, guardians of law of and order, in response to the breakdown of the R.I.C, this was not to be repeated in 1922. In 1922, the anti-Treaty IRA did little to maintain law and order or attempt to revive normal economic conditions and instead engaged in acts of violence and intimidation against perceived civilian opponents. Looting and other acts of violence against civilians conducted by volunteers were largely overlooked, and often even covertly approved off by local IRA leaders.

Goodwill squandered

O’Shea notes that it should not be forgotten that when Free State troops entered Kerry towns in the summer of 1922, and indeed other towns across the south and west where the Free State army had dislodged their anti-Treaty opponents, they were greeted by locals as liberators.

The ordinary people who greeted Free State troops in market towns across Ireland generally felt that the Free State was effectively bringing about stability after years of violence, lawlessness and uncertainty.

A key point of O’Shea’s volume is that this sentiment was not to last. Rather than capitalise on the goodwill felt towards them the Kerry Command of the Free State army squandered this goodwill through their callous brutality, which alienated the people they purported to both represent and protect. While most people in Kerry wanted peace and the anti-Treaty to give up the fight, few could approve of the torture, maiming and at its worst blowing up of men, and women, who were also friends, neighbours and relatives.

The Free State side made little effort to hid their worst actions. In fact, it was only after the Civil War, that O’Shea interestingly, notes that Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy, himself a Free State commander in the Civil War, brought the excesses of the Free State officers in Kerry to heel, and even brought some to justice.

A long political shadow

Richard Mulcahy, National Army Chief of Staff and Free State Minister for Defence, was dogged until his final days by reminders of his decision to implement the execution policy, but in Kerry, so too did resentment towards the Free State fester post 1923.

A resentment which also helped propagate different hues of republicanism in the county in the post-Civil War years. Clare and Kerry saw the highest votes in favour of Sinn Fein in the 1923 election, and Kerry was up until fairly recently an unassailable Fianna Fail redoubt. Anti-Treaty IRA leader John Joe Rice won a seat as an abstentionist TD for Kerry South in 1957, and Martin Ferris in 2002 was the first Sinn Fein TD to actually take his seat in the Dail from outside Sinn Fein’s strongholds in the border counties.

When Free State troops entered Kerry towns in the summer of 1922, they were greeted by locals as liberators. A key point of O’Shea’s volume is that this sentiment was not to last.

Of course Sinn Fein electoral success at these times was also rooted in protest against current governments rather than specifically because of Civil War atrocities. Nonetheless, the persistence of anti-system republicanism in Kerry has also been described as being the product of vivid memories of Free state brutality. Indeed, leading figures in the anti-Treaty IRA in the Civil War would prove to be staunch backers of the Provisional IRA in later years.

In the immediate post Civil War period the new Fianna Fail party were able to capitalise on the Civil War and humiliate their Cuman na nGaedhael/Fine Gael opponents, by having Stephen Fuller the sole survivor of the Ballyseedy atrocity, as a TD for north Kerry – in effect to remind the Fine Gael side constantly of Ballyseedy, and their lack of credibility in the eyes of Fianna Fail.

Fianna Fail was in many ways the great success story of the Civil War.

De Valera in the years just after the Civil War feared that for as long as his side stayed out of the Dail that Free State politics would come to be defined by a clearer left -right divide between Cumann na nGaedhael and the Labour Party – leaving him and his supporters isolated. DeValera’s legacy or success was his ability in fashioning a party that appealed to nearly all sections of early 20th century Irish society, indeed to many people who cared little for Civil War divisions.

Nonetheless, despite appealing to sections of society who cared little for civil war politics, Fianna Fail made the Civil War intrinsic to its identity. In a convoluted irony, majority opinion now gave a type of post endorsement to the anti-Treaty side, despite being having been previously opposed to it in the Civil War. Indeed, the great success of Fianna Fail was in understanding the need for a broadness of appeal and to have a malleable nature.

Longstanding support for militant republicanism in Kerry, up to the present day is in large part a legacy of the brutality of the Civil War.

This rather convoluted sense of self identification with the battle against the Free State in 1922-23, carried on despite Fianna Fail in 1932 taking over and administering the state it had effectively tried to destroy ten years previously.

And Fianna Fail’s self-proclaimed republicanism also survived their subsequently imprisoning and then executing IRA members during the Emergency or Second World War, whilst still paying sentimental lip service to their anti-establishment roots of 1922.

In a striking analogy with 1922 Kerry republicans found themselves imprisoned in the 1940s by the people with whom they had previously fought with side by side against the Free State.

Perhaps had Richard Mulcahy introduced a less brutal policy, which alienated many supporters and potential supporters, the anti-Treaty side may not have been subsequently so successful. But equally had DeValera not been such an astute politician who ensured that Fianna Fail was able to emerge from the conflict as a malleable force, things may also have been different.

Perhaps there might have emerged a relatively straight forward left – right divide between Labour and Cumann na nGaedhael while the remnants of the anti-Treaty position, if they had been treated more leniently but also if they lacked political leadership, would have been relegated to a position of irrelevancy or extremism.

But to return to O’Shea’s volume, these questions of legacy, the complicated and non-straight-forward nature of Civil War and its aftermath are considered by O’Shea, with sensitivity and respect together with an obvious expertise in the available secondary and newly released primary source material. All of this is presented in an engaging and clear prose style.

O’Shea with this volume hopes to present an unbiased and straightforward account of some of easily the most tragic events in his county’s recent history. He has achieved his set task admirably in what amounts to one of the best publications on Kerry’s Civil War experience, but also one of the best volumes produced in this decade of centenaries.