‘A modification of the Treaty’: W.B. Yeats, W.T. Cosgrave, and secret peace talks in London during the Civil War

By Karl O’Hanlon

In February 1923, as the Civil War raged in Ireland, W.T. Cosgrave secretly met Irish peer Lord Granard and senior British official Baron Southborough in London to discuss how the British might facilitate peace negotiations with anti-Treaty forces. The meeting was arranged by the poet and Free State Senator, W.B. Yeats. This article examines the meeting, and the possibility that a British willingness to modify the Treaty was rejected by Cosgrave.

‘An alleged mission’: W.B. Yeats and the secret peace talks

The year 1926 was a crucial one for the twenty-six counties. Four years after the establishment of the Free State, in an attempt to republicanise the state from within (and chart a route out of the political wilderness) Éamon de Valera and group of deputies split from Sinn Féin to found Fianna Fáil. Abolition of the oath of allegiance to the British Crown was a central plank of the party’s strategy.[1] The atmosphere was febrile.

At a performance of Sean O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars on 11 February, a co-ordinated protest led by republican women including Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington broke out in response to the play’s perceived insult to the nation and the dead of the Rising. Stink bombs were thrown, and an actress assaulted, while the police were called in as they had been during the Playboy riots nearly two decades earlier.

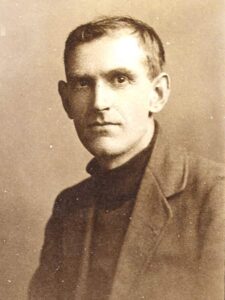

Relishing the opportunity to resume an old role, W.B. Yeats, who had been nominated to the Senate in December 1922, took to the stage: ‘I thought you had got tired of this. It commenced fifteen years ago. You have disgraced yourselves again. Is this to be an ever-recurring celebration of the arrival of Irish genius?’[2]

In February, Yeats was also implicated in a minor political brouhaha that concerned events during the Civil War. As The Irish Times reported, during a by-election rally in Dundrum for independent Patrick Belton, in the context of insisting that the oath of allegiance to the Crown was not the immoveable object that the Free State government insisted it was, republican Dr Patrick McCartan made a startling revelation:

In 1923, when it looked as if the struggle between the Free State and the Republican forces would continue indefinitely, President Cosgrave sent Senator W.B. Yeats to London to confer with the British Government regarding the abolition of the oath of allegiance. On his return Senator Yeats reported that the British Government would be quite agreeable if it meant peace for the country. “In other words,” said Dr. MacCartan [sic], “they could have the abolition of the oath tomorrow, and they could have a healthy Opposition in the Dáil if the oath were removed. It is being kept because the party in power wants to keep it in power.”[3]

Denials from Yeats and Cosgrave appeared the next day in the same newspaper. The President’s secretary quoted the reported speech verbatim, adding, ‘I am directed by the President to say that the reported statement is untrue.’

Yeats wrote from Merrion Square to contradict the allegation: ‘President Cosgrave did not send me to London, nor did I see any member of the British Government on the subject, nor did I make any such report to the Irish Government.’[4]

The wording was obviously legalistic, and on 11 February, McCartan challenged Yeats in The Irish Times: ‘Senator Yeats, I am confident, will not state a lie. Will he, therefore, deny that he saw prominent Englishmen on the subject, and that he reported the result to President Cosgrave?’[5] In a letter to William J. Maloney, McCartan mentions a further denial by Cosgrave, while Yeats remained silent.[6]

In 1926 republican Patrick McCartan alleged that W.B. Yeats had almost mediated a revision of the Treaty to end the Civil War in 1923.

McCartan’s information about Yeats’s secret mission had come from Senator James G. Douglas, who had also been involved in later peace negotiations during the civil war.[7] In McCartan’s recounted version of Douglas’s information, Yeats had ‘interviewed prominent English statesman’ on the possible modification of the oath, reporting this to a ‘delighted’ Cosgrave. Yeats allegedly told Douglas, ‘[Cosgrave] did not seem so enthusiastic after he had spoken to Mr. O’Higgins and Mr. Hogan’.[8]

The Minister for Home Affairs and the Minister for Agriculture respectively, Kevin O’Higgins and Patrick Hogan, along with Desmond FitzGerald, formed ‘a formidable troika’ in Cosgrave’s Treatyite government.[9]

In a letter to McCartan, Douglas lamented the breach of good faith in publicly divulging a private conversation, indulging in verbal quibbling without denying the allegations.[10] McCartan replied in an angry (possibly sectarian) letter:

A poor memory is a political asset but mine is exceptionally good […] Let me assure you therefore that the statements in my letter to the Independent may be accurate or otherwise but they are exactly as told by you and on Yeats’s reference to O’Higgins and Hogan I quoted you verbatim.[11]

‘I had to play a dirty game,’ McCartan wrote to Maloney, quoting John O’Leary: ‘“Not by men who love ease, money, health, or even reputation more than country can it be hoped freedom will be won.”’[12] Although some of the details in his account are impossible to verify, McCartan’s allegations were substantially correct, as Bernard G. Krimm and Roy Foster conclude in their treatment of the episode.[13]

Though later denied by both Yeats and W.T. Cosgrave, McCartan’s allegations were substantial correct.

In fact, Yeats’s mission resulted in a significant meeting between Cosgrave and British statesmen that has not previously come to light. In January, Yeats was in London to canvass British authorities about the return of the Hugh Lane pictures. Lady Gregory’s nephew Hugh Lane had died in the sinking of the Lusitania, with Yeats and Gregory taking up a decades-long battle to return from London his collection of modern French masterpieces as the foundation of a modern art gallery in Dublin.[14]

Their wrangles hinged on Lane’s change of mind in the run up to his death, and a February 1915 codicil to his will. The war hampered any chance of success: ‘People are very despondent about Ireland and that is against us,’ Yeats wrote to Lady Gregory on 29 January.[15] He would be forced to try another tack.

On 3 February, he wrote to his wife George from London:

I am busy writing & dictating system. I am also through Lord Granard asking questions of the Government to try & find a way to peace—or rather to bring it a little nearer… Certain things seem to me necessary to make the Irish situation correspond to facts as those facts are altered by opinion here. I feel in this I keep within my province for every search for reality is kin to every other.[16]

In characteristically Yeatsian terms, the letter touches on the convergence of poetry and politics in his life. Still working on his ‘system’—the elaborate occult cosmology A Vision first published in 1925—Yeats was concerned that the increasingly bitter civil war scuppered any likelihood of British concessions on the Lane pictures, hence the necessity to ‘make the Irish situation correspond to facts as those facts are altered by opinion here’.

For Yeats, there was no abdication of his poetic responsibility in this secret mission: at root, it was the same ‘search for reality’. A bit too on the nose, then, rather than the immediate threat to his and his family’s life and property, it would appear that the impetus for Yeats to initiate peace plans to end civil war—a ‘vendetta on a national scale’[17] which would determine the shape of politics on the island for the next century—was his desire to repatriate the Lane paintings. The fact that such a quixotic mission brought the Irish Government into private conversations with senior British statesmen is quintessential Yeats: the scheming dreamer somehow conniving to be in the midst of it all.

On 5 February, he wrote again to George:

I am trying to get a modification of the treaty, a slight modification that might have a great effect & bring peace much nearer. I have just been with Grannard [for Granard] & Southborough; & Grannard is trying to make an appointment for me with one (of too [sic] or three possible men) who might negociate [sic] with the Irish Government and the Republicans & the English Cabinet. Southborough was hostile at first but I talked him over completely.[18]

Bernard Forbes, 8th Earl of Granard was an Anglo-Irish peer who sat alongside Yeats in the Senate. Francis Hopwood, 1st Baron Southborough had longstanding interests in Irish affairs: as a civil servant, he had served as Permanent Under-Secretary of State to the Colonies, and in 1917 was appointed Secretary to the Irish Convention, the body tasked with examining Home Rule in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising.

Yeats wrote at the time, ‘I am trying to get a modification of the treaty, a slight modification that might have a great effect & bring peace much nearer’.

A former privy councillor, Southborough had connections with prominent members of Andrew Bonar Law’s government, as well as considerable experience as a negotiator; he had sat on the Ridgeway Committee into South African affairs after the Boer War, and as early as November 1919, he had urged a peace conference between the British and representatives of Sinn Féin.[19]

On 6 February, Granard wrote to Yeats enclosing Southborough’s suggestions for possible go-betweens, a list that included Lord Shaughnessy; John French, the Earl of Ypres (latterly Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland); Hamilton Cuffe, the 5th Earl of Desart; and the Archbishop of Canterbury. Granard considered most of these unsuitable, but ‘if it thought essential to have an Irishman,’ leaned towards Desart, adding Richard Hely-Hutchinson, 6th Earl of Donoughmore as another possibility.

Ultimately, however, Granard believed Southborough himself ‘much the best man to undertake the negotiations’.[20] ‘It is true that the negotiations will really be with Englishmen (the Cabinet, not Irishman)’, Southborough conceded to Granard, not ruling himself out. In the letter to Yeats, Granard urged the poet to ‘find out the views of the Irish Government’.

Events moved quickly. On 10 February, Yeats was back in London, arranging a séance at the College of Psychic Studies. He wrote cryptically to George: ‘Grannard [sic] will have seen C last night. I lunch there today to hear result. Had some talk with Hogan on journey over. He is full of warlike spirit, & represents the obstacle.’[21] On the same day—presumably after the lunch mentioned—he wrote again:

I have just wired “Negociations [sic] going as well as possible.” G. saw C last night and says C enthusiastic about idea. S. is now to see authorities. I am too excited to work at system as I intended, & will probably stray through the British Museum or the National Gallery. If it succeeds I shall be able to do much for the national gallery in Dublin & for the theatre. C. brought another with him—K—which gives as I think weight to his decision [sic].[22]

On 9 February, the day before Yeats’s letter, Granard had met privately with W.T. Cosgrave (‘C’) and Hugh Kennedy (‘K’), the Attorney General and one of the architects of the Constitution of the Irish Free State.

De Valera ‘must be captured and executed’: the Southborough talks

The pair were part of an Irish delegation to London that included Patrick Hogan, the Minister for Agriculture, whom Yeats had encountered on the ferry and saw as the belligerent wing of the Treatyite establishment.

The primary purpose of their visit was to negotiate detailed transfer of powers and financial matters, resulting in the Hills-Cosgrave British Irish Financial Agreement of 1923.[23]

As Ronan Fanning describes, no record of the talks has survived. They concerned land purchases, resolved by the Irish government undertaking to collect and pay annuities, as well as the finance for the 1923 Land Act, guaranteed by the British Government.

A senior Free State delegation met the British government in February 1923 ostensibly to discuss a new land and financial matters.

The Executive Council met on 13 February and approved the agreement, but the minutes give no detail as to the negotiations or the provisions of the settlement, or even that an agreement had been signed. These secret talks later provided political capital in Fianna Fáil’s Economic War: both the lack of transparency involved, and the fact the agreement had not been ratified in the Dáil.[24]

In 1937, De Valera’s paper The Irish Press alleged that the February 1923 negotiations were responsible for the arrest, deportation and interment of London-based republicans such as Art O’Brien.[25]

Even at the time, rumours swirled that the talks in London were in some way related to recent appeals by captured IRA deputy chief of staff Liam Deasy for a ceasefire, with The Cork Examiner insisting that ‘any connection with overtures of peace is unfounded,’ that the civil war was ‘a domestic matter’, and that ‘the intervention of the British Government has been neither tendered nor sought.’[26] As Fanning writes, ‘the 1923 agreement is the most obscure and controversial of the Anglo-Irish financial agreements of the nineteen-twenties’, but a sidebar to the talks, which concerned the fratricidal war and possible ways out of it, have remained until now even more mysterious.

Granard wrote to Southborough on 9 February, presumably just after his private meeting with Cosgrave and Kennedy in his London residence, Forbes House:

My dear Southborough,

Will you please arrange to dine here tomorrow to meet the President. He is quite taken with the idea we discussed the other night. The President lost his evening suit when his house was burnt down, so will you come in Morning dress. We propose dining at 8 p.m.[27]

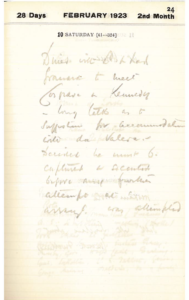

The following day, 10 February, Cosgrave and Kennedy met privately with Granard and Southborough. In a scrawled note, Southborough committed to his diary:

Dined with D. and Lord Granard to meet Cosgrave & Kennedy—long talk as to suggestion for accommodation with De Valera. Decided he must be captured and executed before any further attempt at an arrangt. was attempted.[28]

Southborough’s diary entry is possibly the only record of this extraordinary meeting in which, if Yeats is to be believed, the possibility of modifying the Treaty appears to have been discussed by the head of the Free State government and a senior British official.

The nature of the discussion is shrouded in mystery. Did it centre on the oath? If so, given that McCartan’s allegation of its rumoured abolition is improbable, what form was the proposed modification to take? Were the talks a personal initiative of Yeats, Granard, and Southborough, or did they have the tacit approval of the British and Irish governments?

It is unknown the extent to which Southborough undertook enquiries with members of the British government, or whether such overtures would have been acceptable to the die-hards in Law’s Cabinet, or for that matter either De Valera or the IRA Executive, but what is clear in any case is that the proposal was rejected from the Free State side before it could wither elsewhere.

It is unclear who ‘D.’ is. The most likely contender is Lord Donoughmore: on 19 February, De Valera reported to the IRA Executive that the anti-Treaty position was boosted by rumours concerning the Earl of Midleton, Lord Donoughmore and Bonar Law’s interest in instigating negotiations with De Valera.[29]

Baron Southborough recorded: ‘long talk as to suggestion for accommodation with De Valera. Decided he must be captured and executed before any further attempt at an arrangt. was attempted’

Equally, ‘D.’ could be the Duke of Devonshire, Victor Cavendish, Secretary of State for the Colonies and a Cabinet minister in Bonar Law’s Conservative Government. While we only have Southborough’s terse account of the meeting, and we must be cognisant of that fact, prejudicial reference to “execution” in the case of De Valera exacerbates the questionable legality of military courts and scant regard for due process that Seán Enright attributes to the Civil War executions.[30]

The following day, Yeats wrote to George:

To day a check to plans. G. has seen K & C again & after a “long talk” thinks it “quite plain” “that it would be highly dangerous to attempt anything at present”. His note has just come. I won’t know what value to put on this until I hear what was said. I do not know of course what measure of time is covered by “at present”. From all of which you will see what a tangle Hugh Lane left his affairs in. You will notice that G.’s experience has been exactly mine, first comes agreement then comes the hesitation.[31]

The reference to the Lane pictures—rather than a cessation of violence as an end in itself—shows something of Yeats’s obsessiveness, his political bloody-mindedness. A few days later, he had forgotten about his mission, writing to his sister Lily about a message received in a séance regarding a putative ‘Spot the dog, & also… a black cat when I was fourteen. Was there such a cat.’[32]

A month later, however, he returned to the missed opportunity in a letter to Olivia Shakespear: ‘my plans are still government policy but are postponed till peace has come by other means. They will not be used to bring peace but to lay war’s ghost. At least so I am told officially. Unofficially I hear the war party carried the day (this is all very private).’[33] Such a rumour would tally with McCartan’s assertion three years later that Patrick Hogan and Kevin O’Higgins dissuaded Cosgrave from any revisitation of the Treaty, however slight.

The implication that Cosgrave might have been open to modification of the Treaty, including Granard’s assertion that he was ‘taken with the idea’ in his 9 February letter to Southborough and Yeats mention of ‘agreement… then… hesitation’, is surprising. It is certainly at odds with Cosgrave’s public refusal to countenance peace negotiations on that basis throughout the course of the civil war.

As Bill Kissane has examined, Cosgrave denounced the republicans as unlawful ‘freebooters’ without a shred of legitimacy, insisted on decommissioning of arms, suspected De Valera of holding no authority over the anti-Treaty military leadership from as early as October 1922, and believed in the Treaty as an end, rather than a means for Irish political development, negotiated in good faith.[34]

In March 1923, he defended the execution policy as producing the goods: ‘a real peace can only come from good military results.’[35] In May, he replied to De Valera’s terms for peace, including suspension of the oath of allegiance, by describing them as ‘a long and wordy document inviting debate when none is possible’.[36]

Cosgrave had personally suffered as a result of anti-Treaty actions, with his family home at Beechpark destroyed by arson in January 1923, and his relatives coming under attack.[37] Furthermore, as John Dorney argues, the civil war accentuated ideological distinctions between the two sides, with the Free State elite becoming increasingly reactionary.[38]

Southborough’s note regarding prejudicial references to De Valera’s execution upon his capture appear to complicate Kissane’s assertion that Cosgrave was an ‘eminently civilian politician’, and that the Free State side of the Split comprised ‘a largely “constitutionalist” mentality, which emphasised the need for a state to provide for social order, to uphold the rule of law, and to protect individuals from the assaults of others’.[39]

If Cosgrave believed that De Valera was incapable of bringing the anti-Treaty leadership with him—De Valera’s famous description of viewing ‘the tragedy…as through a wall of glass’—why insist to Baron Southborough on his predetermined execution: sentence first, verdict afterward?[40] As a reprisal for his sanguinary rhetoric in the war’s opening salvos? Or, perhaps, an intimation that De Valera’s political star was not yet entirely extinguished?

The intent seems to reflect Treatyite Government thinking: in autumn 1922, General Richard Mulcahy claimed that De Valera would be shot on capture, while Cosgrave forwarded rumours of a plot to assassinate De Valera to Michael Collins with the tart postscript, ‘Is this the Will of the People?’[41]

‘The war party carried the day’: from failed peace talks to ceasefire

Whatever the motives, the possibility, however remote, that the British might revisit the Treaty appears to have been rejected by Cosgrave. He had a particular loathing for De Valera, and the suggestion that De Valera must be captured and executed before any progress could be made resonates with later Free State mythologies of Fianna Fáil’s Chief as uniquely culpable for the civil war, a wrecker fuelled by narcissism and personal ambition.[42]

From Cosgrave’s perspective, re-opening the Treaty would have been an admission that republicans had legitimacy in the dispute. With particular vehemence, he insisted in peace negotiations with the Neutral IRA later in February, ‘I am not going to hesitate if this country is to live and if we have to exterminate ten thousand republicans, the three millions of our people is bigger than this ten thousand.’ As Diarmaid Ferriter remarks, he saw neutrality ‘as moral cowardice’.[43]

Whatever the motives, the possibility, however remote, that the British might revisit the Treaty appears to have been rejected by Cosgrave.

If there was any truth to the fact that Hogan and O’Higgins—the ‘war party’—prevailed over Cosgrave’s moment of hesitation, he evidently required little persuasion: as John Regan writes, ‘O’Higgins and Hogan appear to have represented the consensual view among civilian ministers [in their advocacy of ruthlessness] rather than a sectional approach to the way the war would have to be ended’.[44]

The war rumbled on, although the anti-Treatyite forces were effectively defeated by early 1923. Peace initiatives continued, but the death of Liam Lynch on 10 April hastened the republican acceptance of the need to order a ceasefire on 24 May.[45]

For all that he vented frustration about the failure of imagination represented by the conclusion of the Southborough peace talks, Senator Yeats’s identification with the Treatyite regime was unshakeable. Since the Truce, he had witnessed remarkable sea-changes in old antagonists, including Arthur Griffith: ‘hitherto he has fired at the coconuts but now that he is a coca nut himself he may become milky’.[46] While he would butt heads with the Free State government throughout the next decade, the civil war proved a crucible for fundamental allegiances:

In spite of all that has happened, I find constant evidence of ability or intensity which makes one hopeful… when the news came in of Michael Collins death [sic], one of the ministers recited to the cabinet—or to seven ministers of it—the entire Adonais of Shelley. One strange thing is the absence of personal bitterness. Senators whose houses have burned down (one man has lost archives going back to, I think, the 15th century) speak, as if it were some impersonal tradedy [sic], some event caused by storm or earthquake.[47]

Notwithstanding the relatively high-level nature of the Southborough discussion, hopes for a revisitation of the Treaty and a negotiated end to the civil war proved in vain. De Valera would successfully remove the oath of allegiance in 1933, with Lord Granard providing clandestine intelligence on its progress for Cosgrave, then in opposition.[48]

If the Southborough peace talks reveal anything, it is that no single party had a monopoly on “Impossibilism”. Still, if anyone could be counted on to test the bounds of the politically credible, it was Yeats: ‘If the Pope as a neutral Authority, would agree to store all republican arms in the Vatican, to keep or deliver up again at his discretion, all would be settled. It does not seem to have occurred to him & aparently [sic] no one else likes to suggest it.’[49]

Karl O’Hanlon is Lecturer in English at Maynooth University. His first book, Official Voices: Poets and the Irish State, is forthcoming.

References

[1] See Ronan Fanning, A Will To Power (London: Faber and Faber, 2015), pp. 143-158.

[2] In Robert G. Lowery, A Whirlwind in Dublin: The Plough and the Stars Riots (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1984), p. 31.

[3] ‘Lively Exchanges,’ The Irish Times, 8 February 1926, p. 6.

[4] ‘An Alleged Mission,’ The Irish Times, 9 February 1926, p. 5.

[5] ‘An Alleged Mission,’ The Irish Times, 11 February 1926, p. 6.

[6] Patrick McCartan to William J. Maloney, 4 March 1926, MS 17,675/3/2, Patrick McCartan papers, the National Library of Ireland.

[7] See The Memoirs of James G. Douglas (1887-1954): Concerned Citizen, ed. J.A. Gaughan (Dublin, 1998), p. 102.

[8] ‘Abolition of Oath: Dr McCartan’s Challenge’, The Irish Independent, 11 February 1926, p. 9.

[9] John M. Regan, The Irish Counter-Revolution, 1921-1936: Treatyite Politics and Settlement in Independent Ireland (London: Gill & Macmillan, 1999), p. 89.

[10] James G. Douglas to Patrick McCartan, 18 February 1926, MS 49,581/38/2, Senator James Green Douglas papers, the National Library of Ireland.

[11] Patrick McCartan to James G. Douglas, 22 February 1926, MS 49,581/38/5, Senator James Green Douglas papers, the National Library of Ireland.

[12] McCartan to Maloney, 4 March 1926, MS 17,675/3/2, Patrick McCartan papers, the National Library of Ireland.

[13] See Bernard G. Krimm, W.B. Yeats and the Emergence of the Irish Free State, 1918-1939: Living in the Explosion (Troy, New York: The Whitston Publishing Company, 1981), 66-71, and R.F. Foster, W.B. Yeats: A Life, Vol. II: The Arch-Poet (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), pp. 230-231.

[14] Incidentally, Cosgrave had been involved in the Lane controversy from his time on the Dublin Corporation; see Michael Laffan, Judging W.T. Cosgrave: The Foundation of the Irish State (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 2014), pp. 36-37.

[15] W.B. Yeats to Lady Gregory, 29 January 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats. Electronic Edition, vol. 4: Unpublished Letters (1905-1939), ed. John Kelly et al. (Charlottesville, VA: InteLex, 2002), no. 4272.

[16] W.B. Yeats to George Yeats, 3 February 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4281.

[17] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green: The Irish Civil War (Dublin: Gill Macmillan, 2004 [1988]), p. 140.

[18] W.B. Yeats to George Yeats, 5 February 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4282.

[19] ‘A Bold Suggestion’, The Freeman’s Journal, 1 November 1919, p. 6.

[20] Lord Granard to W.B. Yeats, 6 February 1923, with an enclosure from Southborough (5 February), William Butler Yeats Microfilmed Manuscripts Collection, SC 294, Box 44, Stony Brook.

[21] W.B. Yeats to George Yeats, 10 February 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4283.

[22] W.B. Yeats to George Yeats, 10 February 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4284.

[23] See DIFP, NAI DFA P646, No. 36.

[24] Ronan Fanning, The Irish Department of Finance 1922-58 (Dublin: Institute of Public Administration, 1978), pp. 136-138.

[25] ‘An Infamous Bargain’, The Irish Press, 30 June 1937, p. 10. There was some truth to this allegation: see Mary MacDiarmada, Art O’Brien and Irish Nationalism in London, 1900-25 (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2020), p. 172.

[26] ‘Pres. Cosgrave: Purpose of Visit: No British Interference Sought,’ The Cork Examiner, 10 February 1923.

[27] Granard to Southborough, 9 February 1923, Archive of Francis John Stephens Hopwood, Baron Southborough, Mss. Eng. 7351/5/1-2/57, Bodleian Libraries.

[28] Diary entry, 10 February 1923, Archive of Francis John Stephens Hopwood, Baron Southborough, MS. Eng. e. 3621, Bodleian Libraries.

[29] De Valera to IRA Executive, 19 February 1923, De Valera Papers, UCDA, P150/1647.

[30] Seán Enright, The Irish Civil War: Law, Execution, and Atrocity (Newbridge, Kildare: Merrion Press, 2019).

[31] W.B. Yeats to George Yeats, 11 February 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4285. The Collected Letters give ‘K & G’; editor John Kelly (Oxford) has kindly sent me scans of originals, and I have verified that the second letter is ‘C’ for Cosgrave. I’m very grateful to Professor Kelly for his generosity.

[32] W.B. Yeats to Lily Yeats, 16 February 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4287.

[33] W.B. Yeats to Olivia Shakespear, 22 March 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4304.

[34] See Bill Kissane, The Politics of the Irish Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), pp. 99-125.

[35] Cited in Michael Laffan, Judging W.T. Cosgrave, p. 123.

[36] Cited in Bill Kissane, The Politics of the Irish Civil War, p. 119.

[37] Laffan, Judging W.T. Cosgrave, p.177. Granard’s home in Castle Forbes, Longford, was extensively damaged by a land mine a few weeks after the meeting in London.

[38] John Dorney, The Civil War in Dublin: The Fight for the Irish Capital 1922-1924 (Dublin: Merrion Press, 2017), p. 143. John Regan’s The Irish-Counter Revolution provides an authoritative history of the ideological contours of the Treatyite elite.

[39] Bill Kissane, The Politics of the Irish Civil War, pp. 123, 125.

[40] De Valera, cited in Ronan Fanning, A Will to Power: Éamon De Valera (Faber and Faber, 2015), p. 130.

[41] See John Regan, The Irish Counter-Revolution, pp. 113-114. Cosgrave objected in the Dáil to low-ranking republican lives being taken while prominent Republicans were spared, a barely-veiled threat to the anti-Treaty political leadership; see Laffan, Judging W.T. Cosgrave, p. 121.

[42] On Cosgrave’s antipathy, see Laffan, Judging W.T. Cosgrave, p. 124.

[43] Diarmaid Ferriter, Between Two Hells: The Irish Civil War (London: Profile Books, 2021), p. 95.

[44] John Regan, The Irish Counter-Revolution, p. 122.

[45] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, pp. 228-258.

[46] W.B. Yeats to George Russell [‘Æ’], 12 January 1922, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4047.

[47] W.B. Yeats to Olivia Shakespear, 22 March 1923, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4304.

[48] Granard to W.T. Cosgrave, 23 November [1932?], The Granard Papers, T3765/K/15/2/9, PRONI.

[49] W.B. Yeats to Lady Gregory, 26 December 1922, The Collected Letters of W.B. Yeats, InteLex, no. 4239.