Al Smith, the man who wanted to be president but helped build the Empire state building instead.

By John Joe McGinley

As President Joe Biden whose ancestors hail from Ballina in Co Mayo and the Cooley Peninsula in Co Louth has just announced his visit to Ireland. This article looks at the man who was the first Roman Catholic Irish American to be nominated by a major party to run for the Presidency, Al Smith.

Al Smith was the dominant force in New York State politics for over 20 years.

He was the first politician of national stature to rise from the ranks of urban Irish American Roman Catholic immigrants, in his case, the Irish American immigrants of downtown Manhattan.

He served four terms as New York State governor and ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic candidate for president in 1928 – the first Roman Catholic candidate nominated by a major party. After his career in politics ended, he became the president of Empire State Inc., the corporation that built and operated the Empire State building.

His early life moulded his political beliefs.

Alfred Emanuel Smith was born on December 30th, 1873, to Joseph Alfred and Catherine Smith.

His father was of German and Italian descent and was a civil war veteran who had fought with the 11th New York Infantry regiment, a fighting force raised by Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, a personal friend of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln.

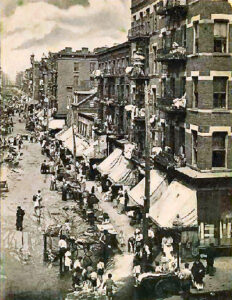

Catherine Smith’s parents were Maria Marsh and Thomas Mulvihill, who were immigrants from County Westmeath. The young Alfred (known as Al) was brought up on the lower east side of Manhattan close to the new Brooklyn bridge, an area he would live in all his life. He often said at stump speeches “The Brooklyn bridge and I grew up together”. (1)

While Al Smith was from a mixed cultural background, he identified most with the Irish American community. He would go on to be one of its most committed advocates and campaigners.

Al Smith had mixed German and Italian as well as Irish ancestry, but he was generally identified as an Irish American.

His father, who owned a small trucking firm, died when Alfred was just 13. The young boy who was then studying at St. James school dropped out to support his family. Those few years in the public school system would be his only formal educational experience.

He served as an altar boy and was strongly influenced by the Catholic priests he worked with. His faith would have a lasting impact on his political beliefs.

Smith found work at the local Fulton fish market where he worked for $12 per week, to help support his family. While he would never attend high school or college, he would later claim he learned more about life and politics by watching people at the Fulton fish market than any college course could teach him.

On May 6th, 1900, aged just 17, Al Smith married his child- hood sweetheart, Catherine Ann Dunn, with whom he would have five children, Two daughters and three sons. Smith remained deeply in love with Catherine all his life.

He developed a love of amateur dramatics and was recognised as a fine actor. He would soon put his smooth oratorical style to effective use as he entered politics.

At the outset, Smith saw himself as a defender of the working man and especially of the Irish emigrants. He became a protege of the Democratic party ward boss ‘Silent’ Charles Murphy, who was a leading figure in the infamously corrupt Tammany Hall organisation which effectively controlled Democratic politics in New York.

Murphy also known as Boss Murphy was responsible for the election of three mayors of New York and three governors of New York State.

While never personally accused of corruption, Murphy and Tammany Hall made Smith’s first political appointment, when in 1895, Smith was appointed as an investigator in the office of the commissioner of jurors.

In 1904 Smith was first elected to the New York State assembly, where he would serve for 11 years. Smith built on his working-class beginnings, identifying himself with immigrants and campaigning as the champion of the working man all his life.

Smith runs for higher office.

In November 1915, Smith again with the help of Tammany Hall was elected Sheriff of New York County. This was a role with large scope for patronage appointments, which would provide loyal followers for his future political ambitions.

Al Smith was now recognised as the leader of the ‘progressive’ movement in New York City and State. The progressive movement had a focus on cleaning up the murky aspects of politics, modernisation of all aspects of life, a focus on family and education, prohibition, and women’s suffrage. It was ironic that Smith had been propelled to power by Tammany Hall, one of the most corrupt organisations in American history and also that Smith was no fan of prohibition.

Al Smith was recognised as the leader of the ‘progressive’ movement in New York City and State

In 1917, he was elected president of the board of aldermen of the City of New York. Al Smith had served his political apprenticeship. Now a seasoned player with a solid support base and strong campaign network, it was time for him to run for governor of New York State.

In 1918, Smith was encouraged to run for New York governor by Boss Murphy and the Democratic Tammany Hall operation. He was also helped by the support of the rising star of the Democratic Party and political strategist James Farley.

In a closely fought election, Smith defeated his Republican opponent Charles S. Whitman. His victory was down to both his personal popularity and the organisation skills of James Farley, who helped deliver the vote of upstate New York, usually a Republican stronghold.

In 1919, Smith gave the famous “A man as low and mean as I can picture” speech at the Carnegie Hall where he made a dramatic break with the publisher and fellow progressive Democrat, William Randolph Hearst the inspiration for Orson Wells film Citizen Kane . (2)

Hearst, known for his notoriously sensationalist and largely left-wing position in the state Democratic Party, was now the leader of its populist wing in New York. He had allied with Tammany Hall in electing the local administration and had attacked Smith while governor for starving children by not reducing the cost of milk.

In his speech Smith denounced William R. Hearst as an assassin of character, an enemy of the people, and an apostle of discord, and his newspapers were called ‘a pestilence that walks in the dark’. (3)

This was a brave thing to do considering the power of the press and the Tammany Hall operation. It was to prove fatal when in 1920 Al Smith lost his bid for re-election when he was defeated by Nathan L Miller as Republican candidates swept the board across the USA on the coat tails of Warren G. Harding’s landslide victory in the US presidential election, held on the same day as the race for governor.

Al Smith takes on the Ku Klux Klan

Al Smith had more work to do for New York and he and Farley immediately began planning for another run for governor.

This would prove to be more successful and in 1922 he secured the second of what would go on to be his four terms as New York governor, when he defeated his old rival Nathan Miller with over 55% of the popular vote. As governor again, Smith became known nationally as a progressive who sought to make government more efficient and more effective in meeting social needs.

He fought for adequate housing, improved factory laws, proper care of the mentally ill, child welfare, and the expansion of state parks.

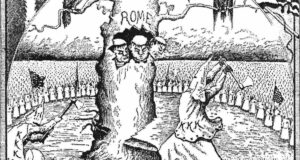

One of Smith’s most formidable opponents within the Democratic Party was the Klu Klux Klan, who were strongly anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant.

In 1924 he not only stood for re-election as governor in 1924 but decided to seek a national platform for his reforming agenda as the Democratic candidate for president at the Democratic convention held in Madison Square Gardens in New York from June 24th to July 9th, 1924.

This was to prove a legendary example in compromise politics, as delegates took 103 ballots to nominate a presidential candidate, which was sadly not to be Al smith. The newspapers called the convention a “Klanbake,” as pro-Ku Klux Klan and anti-Klan delegates fought bitterly over the Democratic party’s future platform.

The Ku Klux Klan was created in Pulaski Tennessee in 1866, in the wake of the Confederate defeat in the American civil War. Members of the Klan led by ex-Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest sought the restoration of Protestant white supremacy through intimidation and violence aimed at the newly enfranchised African Americans and Republican voters and politicians. From the 1870s onwards they saw their primary goal–the reestablishment of white supremacy–fulfilled through Democratic victories in state legislatures across the South in the 1870s.

By the 1920s the Ku Klux Klan, whilst still anti African American, was also rabidly hostile to both immigrants who they perceived as foreigners and Roman Catholics.

It was a powerful force in the Democratic party not only in the southern states but also in the Midwest and Northeast. They were now using this political strength to oppose the nomination of the son of an Irish Immigrant, Roman Catholic Al Smith.

Smith’s leading opponent was former Wilson cabinet member William G. McAdoo, who as a protestant was supported by the Ku Klux Klan. As they were a major source of power within the Democratic party, McAdoo did not repudiate its endorsement.

The convention opened on a Monday and by Thursday night, after 61 ballots, the convention was deadlocked.

Smith and his supporters failed by a slim margin to pass a platform position condemning the Klan. It should be pointed out that the convention also had no African American delegates.

To celebrate this defeat, tens of thousands of hooded Klansmen rallied in a field in New Jersey, across the river from New York City. This event, known subsequently as the “Klan- bake,” was also attended by hundreds of Klan delegates to the convention, who burned crosses, urged violence and intimidation against African Americans and Roman Catholics, and attacked effigies of Smith.

The convention was also notable for the return to the political stage of Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR), who nominated Al Smith. His excellent speech in which he dubbed Smith the ‘Happy Warrior” and praised his socially progressive platform and history, was his first major political appearance since contracting polio in 1921. (4)

As a two-thirds vote was needed to win the nomination, McAdoo and Smith cancelled each other out. There were also scores of vanity candidates each wanting a moment of fame, but with no chance of success. This crowded field prevented either man from collecting even a simple majority of votes and the nomination.

The famous reporter and political columnist H.L. Mencken, who covered the rowdy, sweltering, never-ending convention for the Baltimore Evening Sun, wrote:

“There may not be enough kluxers in the convention to nominate McAdoo, but there are probably enough to beat any anti- Klan candidate so far heard of, and they are all on their tiptoes today, their hands clutching their artillery nervously and their eyes a pop for dynamite bombs and Jesuit spies.” (5)

The conference descended at times into chaos, with numerous rowdy floor demonstrations between ballots, with the chants for “Mac! Mac! McAdoo!” countered by Smith’s forces who cried out, “Ku, Ku, McAdoo.”

McAdoo had come to the convention fully expecting to be the nominee and led through the 77th ballot. Smith now knew he could not prevail and that his sole purpose, was primarily to block McAdoo.

On the 103rd ballot McAdoo finally faced reality and withdrew along with Smith. The nomination was then finally awarded to corporate lawyer and the US ambassador to the United Kingdom, John W. Davis. He would go on to lose the general election to the Republican candidate Calvin Coolidge.

Disappointed but buoyed by his blocking of McAdoo and by extension the KKK, Al Smith concentrated on securing his fourth term as governor of New York. Again, aided by James Farley’s wise council and strategic skills he went on to narrowly defeat Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. the eldest son of former President, Theodore Roosevelt.

Smith runs for the White House

Smith was now recognised as the foremost urban leader of what became to be known as the ‘Efficiency Movement’ in the United States which was noted for achieving a wide range of social and business reforms.

In 1926, Al Smith stood for and won his fourth and final term as New York State governor easily beating his Republican challenger. Ogden Livingston Mills.

Mills would later be a great asset to the Democrats as his incompetent handling of the US economy as Secretary of the Treasury in President Herbert Hoover’s cabinet deepened the economic crisis in the early 30s and helped FDR win the White House.

Four years after his withdrawal from the 1924 convention and with four terms as New York State governor, Smith was now viewed as the front runner for the nomination and the most credible candidate the Democrats could field in the general election.

His old rival William McAdoo decided not to run against Smith. He concluded that Smiths nomination was a foregone conclusion, and his standing would be a futile gesture. The Democratic convention was held in the Sam Houston Hall in Houston Texas over 3 days June 26th to the 28th The convention was broadcast via radio, allowing Smith to follow it from Albany New York.

Smith ran for US President in 1928.

Despite the inevitability of Smiths nomination, his rivals who disliked his Roman Catholicism and ‘Wet’ views on prohibition, made a final attempt to encourage delegates to reject him.

The leader of the Texas delegation, Governor Dan Moody spoke out against his anti-prohibition sentiment by fighting for a “dry”, prohibitionist platform. A compromise pro prohibition Roman Catholic candidate was even suggested, Thomas J. Walsh. However, this attempt was quickly snuffed out. The Smith campaign countered by pledging that despite Smiths own personal views, he would always ensure “honest enforcement of the constitution”.

In marked contrast to the chaotic scenes of 4 years earlier, which took 103 ballots to secure a winner Al Smith was selected as the Democratic candidate for the Election after the first ballot. The boy from Brooklyn had now become the man who was the first Roman Catholic candidate for any major political party in American history. The choice for vice president was also straight forward. At the convention, the party leadership selected Senator Joseph Robinson from Arkansas to balance the tickets regional profile.

Was Smith doomed before he started his campaign?

As Smith basked in the glory of his nomination, storm clouds were already on the horizon.

Firstly, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had acted as Smith floor manager at the convention, delivered his nomination speech. This was received with rapturous applause and even as Smith had secured his lifelong dream of the Democratic nomination, many delegates wondered if they had done the right thing nominating a Roman Catholic.

Was it possible Roosevelt was the better candidate? After all he was a Protestant and a bearer of the Roosevelt name. Theodore Roosevelt was still immensely popular; would FDR fare better than Smith in the general election?

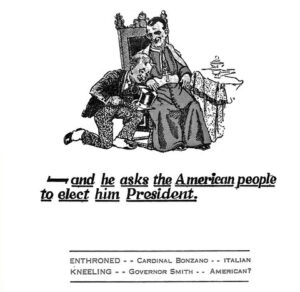

Anti-Catholic prejudice was nothing new in America, it had been common among the early English settlers, reflecting popular anti-Catholicism in 17th century England. Protestant domination of the political and economic system in America allowed myths and superstitions regarding Catholicism to be nurtured and become embedded in large parts of American society.

What was more, descendants of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ Protestant settlers now viewed the influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland, Italy and Eastern Europe since the mid-19th century with suspicion and feared the progress in American society of their descendants of whom Al Smith was now the personification and standard bearer.

Many Protestants carried old fears, and others believed that Smith would answer to the Pope rather than the United States Constitution and the American people.

Another key element in the campaign was Prohibition which was strongly supported by the Southern states. Smith was a renowned ‘Wet’ which meant he was against the prohibition legislation. He had even allowed alcohol to be served at the New York Governor mansion as he celebrated his nomination to run for the presidency. (6)

Smiths ‘Wet’ sympathies were discussed by both Republican and Democratic rivals and many in his own party especially in the ‘dry’ south therefore feared whether a man like Smith would be electable outside of his urban, east coast base.

Finally, under New York election laws, no individual could be on the ballot for both President and Governor in the same election cycle, so Smith could not run for re-election as governor of New York.

Smith knew that to secure the presidency he would have to win his home state of New York, which had the most electoral college votes of any state. He believed that Roosevelt was the only individual capable of defeating Albert Ottinger, the popular Republican Party nominee for governor.

Smith believed that Roosevelt would be capable of drawing 200,000 more votes than any other prospective Democrat. Smith also thought that Roosevelt running for governor would boost voter turnout among Protestant Democrats in upstate New York, without which Smith might lose his home state (and its crucial 45 electoral votes).

Since at least the early 1920s, Roosevelt had planned to seek the governorship, viewing it as a stepping-stone to the presidency. Roosevelt’s long term strategic plan was focused on a gubernatorial campaign in 1932 as a springboard for a presidential candidacy in 1936.

Smith eventually convinced FDR to run but this came at a high price. His trusted advisor James Farley now left his campaign and went to work for FDR. Farley would go on to help Roosevelt secure the governorship and his strategic guidance and political expertise would be sorely missed by Smith in the presidential election.

The campaign

While governor of New York planning his bid to securing the Democratic nomination Smith thought he would be running against the incumbent Republican President Calvin Coolidge, but in 1927 Coolidge announced he would not stand for re-election. The physical strain of the job, as well as the death of his father and his youngest son, had depleted his energy and interest in another term.

Smith would now be up against the Republican candidate Herbert Hoover the US Commerce Secretary.

Smith threw himself into the campaign, but he was not a particularly good campaigner. His campaign theme song, “The Sidewalks of New York”, had little appeal among rural voters, and they found that his ‘city’ accent, when heard on radio, seemed slightly foreign, and his Irish Catholic roots too apparent.

Smith threw himself into the campaign, but he was not a particularly good campaigner and as a Catholic a ‘wet’ and a son of immigrants he had little appear in rural America.

Smith was always up against it in the election campaign, the Republican Party was still benefiting from an economic boom, as well as a failure to reapportion Congress and the electoral college following the 1920 census, which had registered a 15 percent increase in the urban population. This favoured Hoover, whose Republican party was biased toward small-town and rural areas.

The election was the first-time electors had the choice of as Roman Catholic with a chance of the Presidency. It led to the mobilisation of both Catholic and anti-Catholic forces.

The Ku Klux Klan held cross burnings across the country in protest to his nomination and this was a major factor in Smith losing five southern states which were traditionally Democratic strongholds. He also became the first Democratic candidate since Reconstruction to lose more than one southern state.

Smith failed to develop a successful strategy to combat arguments that targeted his faith, once again highlighting how much he missed the support and sage advice of James Farley who ironically helped FDR win the New York governor’s race, while Smith lost his home state and with it the chance of the presidency.

Despite Smiths efforts and even those of Roosevelt in the latter stages of the campaign, it was not yet time for religious prejudice to be set aside and Smith lost to his Republican opponent Herbert Hoover.

Why did Smith lose?

Reporter Frederick William Wile made the oft-repeated observation that Smith was defeated by “the three P’s: Prohibition, Prejudice and Prosperity”. (7)

The buoyant US economy and no American involvement in a war combined with a distrust of a Roman Catholic candidate who many Protestants believed would be dictated to by the Pope in Rome, led to a Republican landslide.

The fatal blow was that Smith narrowly lost New York State.

Smith carried the ten most populous cities in the United States, an indication of the rising power of the urban areas and their changing demographics.

Herbert Hoover benefited hugely from the perception of Republican-led economic prosperity, which, less than a year later, would be proven to have been an illusion with the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression.

Smith was decisively defeated in the 1928 US Presidential election by Republican Candidate Herbert Hoover

As president, Hoover dealt with the financial crisis of 1929 by reversing the low-tax policies of Calvin Coolidge, which turned a short, sharp fiscal crisis into a long, painful depression for the first time in U.S. history.

Some political scientists believe that the election started a voter realignment that helped develop Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition. One political scientist said, “…not until , with the nomination of Al Smith, a north-eastern reformer, did Democrats make gains among the urban, blue-collar and Catholic voters who were later to become core components of the New Deal coalition and break the pattern of minimal class polarization that had characterized the Fourth Party System.” (7)

However, despite the anti-Catholic prejudice every presidential candidate since 1960 has honoured Smith by going to the Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner and in 1960 John F. Kennedy the first Catholic president said “When this happens then the bitter memory of will begin to fade, and all that will remain will be the figure of Al Smith, large against the horizon, true, courageous, and honest, who in the words of the cardinal, served his country well, and having served his country well, nobly served his God”.

Smith and the Empire state building

A defeated Al Smith had seen his presidential hopes crushed and with FDR now in the governor’s mansion with his eyes firmly set on the presidency in 1932 it was time for Smith to reflect on his future.

After the election, Smith moved into business becoming the president of the Empire State corporation. He even arranged for construction to begin on St Patricks day 1930. Just 13 months later, the world’s tallest skyscraper at the time opened on May 1st, 1931, which was a record for such a large project.

Smith sought the 1932 Democratic nomination but was defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt, his close friend and successor as governor of New York. This led to a rift that some say was never healed.

Smith saw the evil of Hitler and was an early opponent of the Nazi regime in Germany. He spoke at a mass rally against Nazism in Madison Square Gardens in March 1933. In 1934 Smith became the Honorary night zookeeper of the newly renovated Central Park Zoo. Despite this being a purely ceremonial title, Smith was given the keys to the Zoo and often took his grandchildren and other guest to see the animals at night.

In 1939 Smith was appointed a Papal Chamberlain of the Sword and Cape, one of the highest honours which the Papacy can award a layman.

Al Smith died on October 4, 1944, of a heart attack, at the age of 70.

Al Smith who FDR referred to as the ‘Happy warrior’ was the trail brazier for future Irish American presidential candidates, including John Fitzgerald Kennedy and more recently, President Joseph Biden.

You can read about more Irish American politicians in my book The Irish in Power.

Sources:

- Slayton, Robert A. (2001). Empire Statesman: The Rise and Redemption of Al Smith. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 13.

- MacArthur, Brian (May 1, 2000). The Penguin Book of 20th-Century Speeches. Penguin (Non-Classics).

- MacArthur, Brian (May 1, 2000). The Penguin Book of 20th-Century Speeches. Penguin (Non-Classics).

- Slayton, Robert A. (2001). Empire Statesman: The Rise and Redemption of Al Smith. New York: Simon and Schuster. ch 1–4

- Boston Evening Sun 8th July 1928

- The New Yorker February 25, 2001

- John A. Ryan, “Religion in the Election of 1928,” Current History, December 1928; reprinted in Ryan, Questions of the Day(Ayer Publishing, 1977) p.91

- Lawrence, David G. (1996). The Collapse of the Democratic Presidential Majority: Realignment, Dealignment, and Electoral Change from Franklin Roosevelt to Bill Clinton. Westview Press. Page 34

John Joe McGinley March 2023