The Irish Defence Forces in the 1930s – Holding Pattern

By Eoin Kinsella

By the time Fianna Fáil took office in March 1932 (supported by the Labour Party), the storm clouds of another European war were gathering. The strength of the Defence Forces was, however, at the lowest ebb in its brief history.

Despite regular and vociferous criticism of Cumann na nGaedheal’s defence policy, once in power Fianna Fáil adopted largely the same approach – maintenance of the Defence Forces in the smallest form possible. As a result the 1930s were largely years of stasis, with few developments of note before the sudden rush in 1938 and 1939 to expand the Defence Forces and prepare for war in Europe.

Irish governments of the 1930s tried to keep the Defence Forces as small and as cheap as possible.

Fianna Fáil’s peaceful accession to power in 1932 was a pivotal moment in the history of Irish democracy, and Frank Aiken’s appointment as Minister for Defence was an important step in defusing any potential tension between the Defence Forces and the Fianna Fáil administration. Though he had succeeded Liam Lynch as leader of the anti-Treaty IRA in 1923, that appointment came in the final weeks of the Civil War and Aiken had been prominent in efforts to avoid conflict in April and May 1922.

The military forces he now inherited were in poor condition; under strength, ill-equipped and dispersed across nearly thirty barracks and posts. Rationalization of personnel in a more suitable, smaller number of barracks was desirable and a long-standing military request. Yet the local economic cost of barracks closures was a political landmine that Aiken was unwilling to approach; indeed, it remains a sensitive topic.

‘The primary purpose … is a political one’[1]

Aiken’s main innovation was to reform the reserve forces. Government policy since 1925 had ostensibly been to develop the regular Army as a small cadre of well-equipped troops, around which a large, trained reserve could coalesce in a time of crisis. The main problem with this policy – in addition to the ongoing failure to properly fund the Defence Forces – was that no coherent scheme for raising a reserve force had yet been implemented.

Aiken announced the creation of a new Volunteer Force in April 1934, alongside a new tactical and territorial organization for the Defence Forces, which came into effect in July 1934. Named in a deliberate homage to the Irish Volunteers of 1913, the new Volunteer Force was expected to attract 20,000 recruits by 1936, complementing or absorbing existing reserve detachments.

Fianna Fail established a new Volunteer Reserve force, intended to draw in republican elements previously hostile to the army.

Taken at face value, the creation of the Volunteer Force was a welcome attempt to bolster the regular force. In truth, Aiken’s motivations were political rather than military, and he pressed ahead with the formation of the Volunteer Force despite the objections of the General Staff. Twenty-one Fianna Fáil supporters were commissioned into the Defence Forces as Area Administrative Officers to help administer the force, while local committees (known as ‘Sluagh’, from which the nickname ‘Aiken’s slugs’ was derived) were created to assist Volunteer units. The Volunteer Reserve, established by Cumann na nGaedheal in 1929 and regarded by Fianna Fáil with suspicion, was disbanded without ceremony in March 1935.

An initial rush of enthusiasm saw 11,594 men enlist in the first twelve months, allowing Aiken to continue to insist that the regular army would be maintained as a small highly trained force, ‘which would serve as a pivot around which might, if necessary, be organized, developed, and trained, the entire man-power of the State.’[2] However, that early flush of success soon proved to be a false dawn.

Recruitment after the initial wave was hampered by problems equipping, training, and administering the force. Removal of unemployment benefits to Volunteers attending training camps and mobilizations affected morale and quickly dampened enthusiasm. More than half of those who enlisted between 1934 and 1939 were discharged for failure to attend training.

The Volunteer Force stood at less than 10,000 men in April 1938, with attendance at local training dropping to just 29 per cent. When the Volunteer Force was reorganized in March 1939, all 7,278 then left were discharged with the option of re-enlisting – just 3,731 chose to do so. Strength had risen to just under 7,000 by September 1939, half of whom were not yet fully trained.

Perhaps the central problem to Aiken’s vision of the regular Army as a highly trained nucleus, around which an enlarged force could quickly coalesce, was that the regular Army itself was poorly equipped and poorly trained. The Volunteer Force merely exacerbated existing problems.

‘The Saorstát can hardly be said to have a Defence Force at all’[3]

After no less than five chiefs of staff between 1924 and 1931, some stability in the General Staff was finally achieved with Lt Gen Michael Brennan’s appointment in October 1931; he held the position until January 1940.

For much of the 1930s the Defence Forces were placed in a holding pattern, and the new government’s treatment of the Defence Forces was virtually indistinguishable from its predecessor, an irony that can hardly have been lost on those who recalled the fears regarding the handover of power to Fianna Fáil in 1932. Financial investment remained static up to 1938, fluctuating between £1m and £1.5m per annum, a sum even less significant than it appears, as the lion’s share was eaten up by wages. Up to 10 per cent of the defence budget also went unspent every year.

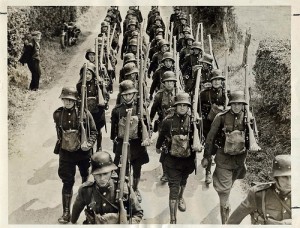

The government’s hands were, of course, somewhat tied by a difficult economic climate. The aftershocks of the 1929 Wall Street Crash were still reverberating around the globe, and in 1932 the Irish government became embroiled in an ‘Economic War’ with Britain, which lasted for six years and further constrained public finances. Investment in military equipment and other matériel, most of which ultimately came from Britain, remained at negligible levels. Personnel numbers reached a nadir in 1931 when less than 5,000 men were in uniform, and hovered just below 6,000 for most of the decade.

In 1935, Aiken informed the Dáil that Ireland was spending less on military equipment than any other European nation, with the possible exceptions of Albania and Bulgaria. The Army’s continued reliance on obsolete or outdated equipment is obvious from its transport budget for 1935/6: 25 per cent of the allocated £62,000 was earmarked for horse transport. Familiarization of troops with mechanised transport and armour remained at an experimental stage, despite longstanding requests from the General Staff for the funding necessary to integrate tanks, armoured fighting vehicles and mechanized artillery. Attempts to establish factories for manufacturing tanks and ammunition were shut down by the Department of Finance.

Nonetheless, in 1934 two Swedish -made Landsverk L60 light tanks were acquired for the Cavalry Corps (formed in 1934), followed by eight Landsverk L180 armoured cars in 1938 and early 1939. Though far from sufficient to adequately defend the state, these purchases did provide opportunities to train personnel using modern equipment. Mechanization of the entire Artillery Corps was finally completed by 1940.

Two of the central elements of the defence policy adopted in the 1920s remained in place under Éamon de Valera’s government: a commitment to neutrality and a guarantee that Ireland would not allow itself to be used as a base for attacking Britain. Tentative defence plans were nonetheless drawn up by G2 (Intelligence) Branch in 1934, recommending the adoption of a guerrilla-style defence, predicated on the assumption that Britain was the power most likely to invade Ireland in order to protect its western flank: ‘There is a constant feeling that having fought the British on this basis before, with a certain measure of success, that it forms the obvious basis on which we should fight them again.’[4]

That plan was quickly dismissed in favour of the recommendations contained in ‘Fundamental factors affecting Saorstát defence problem’, a detailed memoranda examining Ireland’s defensive capabilities and a stark warning of their inadequacy. Drafted in early 1936 by Comdt Dan Bryan of G2 and intended as an internal document, ‘Fundamental factors’ became an unofficial memorandum on the status of the Defence Forces, forwarded by Brennan to Aiken in September 1936. It remains one of the most important statements of Irish defence policy.

The simple truth it outlined was that the state’s ability to mount a credible defence of its territory was non-existent. In September 1936 Brennan referred to ‘Fundamental factors’ in support of his request for an additional investment of at least £1.5m per annum for three years. That was the minimum sum required by the Defence Forces to enable mobilization of its existing ‘paper strength’ of four reinforced brigades (18,800 men, including all reserves):

The existing units are, with few exceptions, far from complete in either personnel, material or equipment. With few exceptions none of the Volunteer Units have even half their establishments of personnel; in addition many units would if mobilized have practically no armament or equipment. For example only 9 out of the 24 Batteries of Artillery required are available. Military units without the necessary personnel and armament are of course useless.[5]

De Valera’s public pronouncements on defence policy frequently caused some concern within GHQ, such as when he declared in June 1937 that ‘we can have no real plan of defence for this country so long as there are parts of our territory which are capable of being occupied by the British at Britain’s will … the proper foundation for national defence is the exclusive control of our own country’.[6]

Head of military intelligence Dan Bryan was deeply critical of underinvestment in defence against the background of a looming European war in the late 1930s.

Noting the comments, Dan Bryan offered a subtle rebuke and a reminder that time was a luxury the Defence Forces could ill afford: ‘A European war may start while the undesirable conditions mentioned by the President continue’.[7] That was a chance the government were willing to take, on the assumption that, for its own safety, Britain would be obliged to come to Ireland’s aid. Such reasoning formed the basis for the consistently trenchant opposition raised by the Minister for Finance, Seán MacEntee, to any proposed increase in defence spending.

Further analysis by the General Staff, presented to the government in late 1937, suggested that an adequate defence of the state would in fact require three divisions, alongside a wide array of specialist units including a coast guard, coastal defence units, a twelve squadron Air Corps (100+ aircraft) and a new naval force – more than 100,000 men in total. The outlay required was at least £4.5m. Military expenditure did in fact increase from 1937 onwards, though at a rate far below what was required to fulfil even the minimalist ambition to complete and equip four reinforced brigades.

Supplies of military equipment began to dry up, as Britain focused on strengthening its own forces. A military mission to America in 1939 had no success in procuring weapons or equipment. One positive element of the concessions gained by de Valera in ending the ‘Economic War’ with Britain in early 1938 was the return of the Treaty Ports, a crucial factor in allowing Ireland to maintain its neutrality when war broke out in September 1939.

As the outbreak of a major war grew increasingly inevitable following the Munich Conference of September 1938, it was abundantly clear to the General Staff that their forces were woefully ill-equipped, capable only of token resistance to any invasion. Repeated warnings to the government had failed to elicit an adequate response. Fianna Fáil had proved itself as unwilling as Cumann na nGaedheal to address glaring weaknesses in the state’s defences.

It had also failed to adequately prepare the public for the enormous national effort that would be required in the event of another major war. As observed by Dan Bryan in 1936, ‘the Saorstát people are … not prepared or educated to the stage at which they are prepared in practice to provide sufficient forces to guarantee even a relative freedom from outside interference.’[8]

When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, Ireland found itself with the barest outline of an air force, no navy, and an infantry hopelessly understrength and undertrained. The Artillery Corps possessed just eight anti-aircraft guns (four 3-inch guns acquired in 1928, and four Bofors L60 acquired in 1939).

The Treaty Ports were well protected with BL 9.2-inch and 6-inch naval guns, while twenty 12-pounder naval guns were stationed at strategic points around the coast. Small quantities of modern infantry weapons had been purchased in the later 1930s, including Bren light machine guns and further quantities of .303 Lee Enfield rifles, but overall the weaponry and equipment necessary for a competent defence of the state on land, at sea, or in the air, were not in place.

Even with the reserve and Volunteer Force, personnel numbers in September 1939 were just shy of 14,000, far short of what was required. A resource-poor organization for much of its existence, the Defence Forces were now starved of perhaps the most important resource of all: time. For the second time in less than two decades, it was about to be called upon to undertake a large scale, rapid expansion to meet what another existential threat to the state it had been tasked to defend.

The Irish Defence Forces, 1922–2022 is published by Four Courts Press and available now in all good bookshops. Dr Eoin Kinsella is managing editor of the Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of Irish Biography.

The Irish Defence Forces, 1922–2022 is published by Four Courts Press and available now in all good bookshops. Dr Eoin Kinsella is managing editor of the Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of Irish Biography.

References

[1] Dept. of Industry and Commerce, memorandum for government on the establishment of the Volunteer Force, 23 October 1933 (NAI. S6327).

[2] Dáil Debates, vol. 55, col. 1795 (3 Apr. 1935).

[3] Dan Bryan, ‘Fundamental factors affecting Saorstát defence problem’, May 1936 (IE/MA/ACS/189/11).

[4] Memo, ‘Estimate of the situation that would arise in the eventuality of a war between Ireland and Great Britain’, Oct. 1934 (IE/MA/EDP/0020).

[5] Michael Brennan to Frank Aiken, 22 Sept. 1936 (UCDA, P67/191. Brigades are subcomponents of divisions. In the Defence Forces, brigades typically consist of three battalions.

[6] Dáil Debates, vol. 67, col. 720 (19 May 1937).

[7] Memo, ‘Present commitments, future policy and programme’, c.June 1937 (UCDA, P71/27).

[8] Bryan, ‘Fundamental factors affecting Saorstát defence problem’.