‘They killed idealism in my soul’ – the end of the Irish Civil War

John Dorney

If the Irish revolution began arguably with the Home Rule crisis of 1912-13, or perhaps with the Easter Rising of 1916, it ended unequivocally with the end of the civil war in the Irish Free State in May 1923.

State power, contested since at least the formation of the republican ‘counter state’ after 1918, was now indisputably concentrated in the Free State government in Dublin the Northern Ireland administration in Belfast. If by no means all of the island’s population was reconciled to either of the new regimes in Ireland, their military and governmental authority was by now immovable.

On May 24 1923, Frank Aiken, the IRA Chief of Staff issued the Dump Arms order, instructing anti-Treaty IRA guerrillas to dump their arms and go home. Famously his order was backed up by Eamon de Valera’s tract to the ‘Legion of Rearguard’ saying ‘the Republic can no longer be successfully defended by your arms’.

Up to twelve thousand prisoners were interned in camps and prisons in the Free State and another 750 or so in jails and prison boats in Northern Ireland. Most were not released until the end of 1923 and some not until 1924. But the anti-Treaty republicans’ military challenge to the post-Treaty order was over.

In Northern Ireland, the most intense period of violence after the Anglo-Irish Treaty had come in the first six months of 1922, when Belfast in particular was convulsed with communal violence and an on-gain-off-again conflict raged along the new border. Pro and anti-Treaty units of the IRA had cooperated in raids over the border into the North.

This initiative collapsed, however, when the southern republican movement tore itself apart over which was the legitimate authority, the Free State’s Provisional Government or the Irish Republic unilaterally declared in 1919, a conflict that formally broke out on June 28, 1922 with the bombardment of the Four Courts.

Though the anti-Treatyites had been driven from the towns and cities of the prospective Free State by August of 1922, the guerrilla war which followed dragged on interminably into the winter of 1922 and the following year.

‘A particular form of warfare’

Liam Lynch, the anti-Treaty IRA’s Chief of Staff, was astute enough to realise that conventional military victory for the dispersed guerrillas under his command was not possible. He wrote to Eamon de Valera, the notional President of the underground republican government that ‘We cannot hope to overthrow the enemy unless there is a big desertion or complete change of the people to our side’ … ‘what I hope for is to bring the enemy to bankruptcy and make it impossible for a single Government Department to function.’[1]

To this end, the IRA, though they did also sometimes mount ambushes, lay mines and assault Free State garrisons, by early 1923, concentrated on attempting to rip away the sinews of the state by destroying its economy and infrastructure.

National Army Intelligence divided the country into two types of area; ‘Districts in which active service conditions prevail in the sternest sense.’ (‘happily scarce’, they wrote) and ‘Areas in which the enemy have been disorganised but not entirely broken. Here we will have zones of sporadic activity…occasional ambushes, sniping… also include railway destruction, assassination, incendiarism, kidnapping, common robbery.’[2]

To the members of the Free State government (formally inaugurated a year after the signing of the treaty in December 1922), notably Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins, ‘It is not a war properly so called’, but ‘organised sabotage and disintegration of the social fabric’.[3]

To him, as important as defeating the remaining ‘active irregulars’ or anti-Treaty IRA columns, was cowing the ‘passive irregulars’ as he called them, who used the disordered conditions to avoid paying taxes, or rates, to seize land or to stage illegal strikes and boycotts.

Similarly, many National Army officers dismissively reported that anti-Treaty support could be found among rural people who benefited from ‘loot’ taken by the guerrillas or from not paying taxes. As one military intelligence officer put it, republican or ‘irregular’ support came from, ‘those who have evaded their lawful obligations such as payments of rates, taxes and have a more or less selfish interest in promoting a state of lawlessness.’[4]

It was a melancholy reversal of a movement (or at least one part of it) that had idealised ‘the people’ and their support for guerrilla war in 1919-21.

While many were dismissive of the anti-Treaty war effort, others noted that though no longer militarily formidable by the close of 1922, the ‘irregulars’ (anti-Treaty) campaign was sapping the authority of and threatening to bankrupt, the new Free State. Patrick Hogan, the Minister for Agriculture, wrote in January 1923, ‘In my opinion the civilian population will surrender definitely before too long if the Irregulars are able to continue their particular form of warfare … Two more months like the last two months will see the end of us and of the Free state’.[5]

To bring it to an end they had embarked on a policy of executions in late 1922, an initiative was greatly expanded in early 1923 – a backhanded acknowledgement that Liam Lynch’s strategy of economic attrition was indeed biting.

Executions, surrenders and reprisals

In January 1923, alone thirty-four republican prisoners were shot by firing squad, compared to eighteen in November and December 1922. A total of 81 would be shot by the of the war and another 400 sentenced to death and effectively held as hostages.

While far more republicans were imprisoned unharmed than executed, the threat of death by firing squad hung over everyone who was captured bearing arms ‘without the proper authority’ or ‘aiding and abetting’ attacks on state forces.

But the policy of executions included a carrot as well as a stick. Any republican guerrilla who surrendered, handed in his or her arms and ‘signed the form’ pledging not to bear arms against the government was spared further legal consequences of any kind. When executions were suspended in February 1923, and an amnesty offered, many did indeed come in to surrender.

The most famous example was senior republican leader Liam Deasy, who after capture called on the men under him to surrender.

Around the country many rank and file republicans came in either alone or in units to give up their arms and ‘sign the form’ in February 1923. In Cork on February 26 it was reported that pro-Treaty troops had taken the surrender at Clonakilty of Cornelius O’Leary, with .45 Webley 17 rds. Felix Connelly with 2 shotguns, John Cronin with large number of mills bombs. ‘All signed the form’.

In Kerry, on 28 February it was reported that Intelligence officer David Neligan took the surrender of ‘Kilmoyley column of Irregulars’ led by Tom O’Driscoll. He and all 12 men under him reportedly ‘signed the form’ and were released, but were ‘Rather delicate about having their surrender published’. On the same day, Dan O’Sullivan Kerry ‘Irregular Brigade Quartermaster’ and Pat Sheehan, Brigade Adjutant reportedly surrendered at the Castleisland post without their arms. And these are merely representative examples[6]

This was not a pattern that had been seen in the war against the British and the Free State government hoped that it marked the beginning of the end of the guerrilla war.

By the spring of 1923, anti-Treaty morale was low. In the republican heartland of south Munster it was reported to IRA command that the population was unfriendly, and ‘plenty of information is supplied to the enemy’, ‘discipline is bad’ with men questioning orders and ‘we are constantly harassed by the enemy’.[7] The end was coming and most anti-Treatyites knew it.

This did not spare some areas of the Free State, most notably County Kerry, from a final bloody spasm of violence in March of 1923. There, National Army troops responded to the deaths of five of their men by a trap mine at Knocknagoshel with a series of notorious reprisals beginning at Ballyseedy near Tralee in which eight prisoners were blown up, followed by four more near Killarney and another five at Cahirciveen.

While unique in their intensity, events in Kerry conformed to a pattern in which National Army troops, frustrated and resentful of the continuing deaths of their men, increasingly carried out ‘roadside executions’ of captured anti-Treatyites. Areas such as Dublin, Wexford and Mayo all saw a flurry of such killings in March-April 1923.

The anti-Treaty campaign, for its part, expanded in 1923 to include a sustained campaign of house-burning of Free State supporters, which included, though was not confined to, the ‘Big Houses’ of the former mostly Protestant, landed elite. From March they also put a ban on public entertainments and placed bombs at theatres and cinemas which defied it.

All of which brings us to the question of why a political settlement was not found earlier to end the bloodshed and destruction.

Peace moves

What divided the warring factions in the south of Ireland was not so much ideology – both were Irish nationalists and in many cases former comrades. Nor can the bloodshed really be explained, necessarily, in attitudes to the Treaty settlement.

Pro-Treaty leader Michael Collins had famously described it simply as a ‘stepping stone’ to full independence and his successor (after Collins’ violent death in August 1922) as National Army commander, Richard Mulcahy had once said that he ‘did not like a single article’ of the Treaty.[8] Rather it was fundamentally about state power and legitimacy.

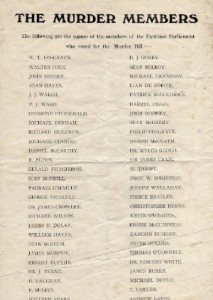

The Free State government’s position was that the Treaty had been approved by a vote of the Second Dail in January 1922, a decision subsequently endorsed by the electorate in the general election of June 1922. The Government led by W.T. Cosgrave in 1923 therefore represented the ‘will of the people’ and no compromise was possible, no negotiations necessary, with those who were conducting an illegal armed rebellion against it.

The anti-Treatyites’ position was that, yes, they stood for the Irish Republic declared in 1919 against voluntary entry, as they saw it, into the British Empire by means of the Treaty and the Free State. But they, not the Free State, were the aggrieved party in the Civil War, attacked without warning by the pro-Treaty government on the orders of the British, while they were still earnestly striving for compromise.

Anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch wrote ‘Since the attack on GHQ Four Courts and the splendid rush to arms of [the] IRA in defence of the Republic against domestic enemies we are finished with a policy of compromise and negotiation unless based on recognition of the Republic.’[9]

And Eamon de Valera, doubtful though he was of the utility of continuing military resistance by 1923 would regularly reiterate the same point; The pro-Treaty government was merely a British installed military junta, he insisted and war had been declared on the ‘soldiers of the Republic’ before the Third Dáil – elected in June 1922 – ever got a chance to meet.[10]

The crux of this was that for the pro-Treaty government, all there was to talk about was on what terms the ‘irregulars’ would hand in their arms and surrender, whereas for anti-Treaty republicans, ‘peace’ meant a political settlement in which the Treaty was revised. The latter, the Government would not countenance. For this reason, various peace moves in 1923 failed to achieve anything.

Interestingly, it was in Free State’s Upper House, the Seanad or Senate, an institution hated by anti-Treaty republicans due to its strong representation of ‘Anglo-Irish’ grandees and former unionists, that many peace initiatives originated. Various Senators, including Andrew Jameson, James Douglas and the celebrated poet W.B. Yeats, attempted to mediate between the two sides in the spring of 1923.

These came to nothing however. Karl O’Hanlon has shown that the Cosgrave government (and indeed the British) were uninterested in a proposed compromise that would remove the Oath of fidelity to the British monarch from the Free State’s constitution in February 1923. ‘Lawful authority’ as they saw it, as well as the fulling workings of the state – in working courts and police, property rights and tax collection had to established unequivocally and by force if necessary.

Nor was unity to found in the shared religion of most of those on either side. Whereas the Papacy, via its envoy to Ireland, Archbishop Luzio, wanted to mediate a peaceful compromise to the Civil War, the Catholic Church in Ireland itself was firmly committed to the pro-Treaty line that the ‘irregulars’ were simply engaged in unlawful rebellion against a legitimate, elected Irish government.

Similarly, an initiative by the ‘neutral IRA’ a body led by former Cork IRA officers Florence O’Donoghue and Sean O’Hegarty to persuade the anti-Treaty IRA to call off their armed campaign in early 1923 come to nothing. Liam Lynch dismissively remarked that ‘they may be discarded as of little consequence’. [11]

Dump Arms

By the spring of 1923, senior IRA figures such as Tom Barry as well as anti-Treaty political leader Eamon de Valera were arguing that it was time to call off their campaign. Lynch however maintained to the last that ultimately the Free State would collapse, if only the guerrillas persisted long enough, which would lead ultimately to a renegotiation of the Treaty on republican terms.

Only the death of Lynch, in April 1923 – shot as he was fleeing a round up in the Knockmealdown mountains – made it possible for the republicans to call off their campaign.

The anti-Treaty IRA Executive met again on 26–7 April, in the wake of Lynch’s death, elected Frank Aiken as the new Chief of Staff and agreed to issue a ceasefire order or ‘Suspension of all offensive Operations’, to come into effect on April 30.

De Valera attempted to open peace negotiations with the Government via Senators Jameson and Douglas, but the government replied that ‘all political issues shall be decided by the majority vote of the elected representatives of the people’ and ‘the people are entitled to have all illegal weapons taken into the custody of the Executive Government’; a formula de Valera rejected as ‘submission pure and simple.’[12]

Needing to end the war, but not willing to surrender openly, de Valera and Aiken came upon another formula, ‘Dump Arms’. The IRA would not surrender, but they would bury their weapons and go home. The order was issued on 24 May 1923.

An untidy ending

Historians naturally use this date to mark the end of the Irish Civil War and certainly this was the end of active guerrilla warfare on the part of the anti-Treatyites. As far as the government was concerned though, military law would have to continue for the better part of the rest of 1923 before state security was assured. It began releasing prisoners in the second half of the year, but it was not until after a mass hunger strike in November and December 1923 that the majority were freed.

Even then, the highest-ranking republican leaders, including Eamon de Valera himself (arrested in August 1923), were not freed until mid-1924 and it was at the end of that year that an amnesty was issued for all politically motivated acts committed in 1922 and 1923 up to the Dump Arms Order.

Until this point there were still several residual columns of anti-Treaty IRA men on the run in several districts, notably parts of counties Cork, Kerry and Leitrim.

Before law and order could be fully handed over to the unarmed Civic Guard, moreover, the National Army was used to put down land seizures and a major strike by agricultural labourers in east Waterford in the summer of 1923. It was only after this point the Free State’s military, bloated to nearly 60,000 personnel at its height (technically an army of such a size as this was a breach of the Anglo-Irish Treaty), began to be demobilised.

At the same time, the pro-Treaty government quietly nudged the anti-Treatyites into electoral politics, allowing them, including many imprisoned candidates, to run in the General election of August 1923.

‘Scarred by bitterness’

The end of the Civil War cemented the existence of the Irish Free State, established under the Treaty. It also all effectively guaranteed the continued existence of Northern Ireland. Indeed it was the Free State, not Northern Ireland, which first erected a customs barrier along the new border in April 1923 in order to raise much needed revenue.

While the final shape of the Northern state was not settled until the collapse of the Boundary commission in late 1924, by this point the Dublin government had long given up on any idea of shifting the border by force.

But alongside just short of 2,000 graves, the violence of 1922-23 also saw the death of idealism and the end of what we now refer to as the Irish revolution.

Anti-Treatyite Todd Andrews recalled that after the Civil War he was ‘unimpaired in health but with a mind ineffaceably scarred by bitterness. I believed the Free Staters had reduced the status of the nation to that of a materialistic province of Britain, still occupied in part by British troops, governed by what appeared to us Republicans to be a clique of Castle Catholics.’[13]

On the other side of the Treaty divide, pro-Treatyite Laim de Roiste would write, ‘it was the actions of the Irregular-republicans that killed idealism in my own soul…in connection with this country and its people and I know they killed it in many others as well.’[14]

It was a bitter and destructive legacy.

Notes

[1] De Valera-Lynch correspondence 14 December 1922 and 28 December 1922. De Valera Papers, UCD p.150/1749.

[2] Military Intelligence Command Department Reports 1922-1923 (Military Archives) MIPR-02-01 No:55

[3] O’Higgins memo 11/1/1923 cited in Army Inquiry 1924, Mulcahy Papers, UCD P7/C/21.

[4] Irish Military Archies (IMA) IE/MA-CREC-01 General Military reports 1923-1924

[5] Cited in Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish Civil War, (Dublin 2004) p. 222.

[6] All taken from Reports to Executive Council 1923 IE/MA-CREC-02

[7] OC 1 Southern Division report March 1923, Moss Twomey papers, UCD, P69/25

[8]Quote in John Regan, the Irish Counter Revolution, (Dublin 2001) p.41

[9] Lynch to O’Malley, 25/7/22, in O’Malley and Dolan, No Surrender Here!, The Civil War Papers of Ernie O’Malley, (Dublin 2007) p. 68.

[10] De Valera to P Gaffney TD, 23/10/22 De Valera Papers P150/1647.

[11] IRA Intelligence January 1924, Twomey Papers UCD P69/81.

[12] For IRA Executive meeting De Valera Papers UCD P150/1740, for government response, Cabinet Minutes. 8/5/1923, Mulcahy Papers UCD P7/B/247.

[13] C.S Andrews, Dublin Made Me, (Dublin 2008) p. 326.

[14] Quoted in Fearghal McGarry, Eoin Duffy A Self Made Hero, Oxford 2007, p.170.