War along the Border: Ireland 1922

The second in a two-part article on the Irish War of Independence in the border counties. Part one here. By John Dorney

At the time of the truce of July 1921, a fitful peace descended on the counties that the 1920 Government of Ireland Act had designated as the border between Northern and Southern Ireland.

The Truce July -December 1921

While negotiations played out in London between the Irish delegation and the British government, the border began to take shape on the ground.

The Northern Ireland parliament opened in June 1921 and in November of that year, executive powers, including control over policing and security, were extended to the Northern government. Its much-feared armed auxiliary police, the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) were remobilised once the Northern government received executive powers, and patrolled the Northern side of the border.

Nationalists on the southern rim of the new border zone were scornful of the new Northern Ireland state and most thought it would not last. The local nationalist newspaper, the Anglo Celt, opined that the Northern Parliament was, ‘A discredit to a third rate creamery’. With ‘overpaid ministers’, and a ‘huge police force, one policeman for every ten inhabitants’[1].

Meanwhile the IRA, free under the Truce, from persecution and arrest, organised training camps throughout the region. Most of its pre-Truce leaders in the region rose further in the organisation during the period of ceasefire.

Sean MacEoin of Longford and Paul Galligan of Cavan were released under the terms of the Truce and resumed their commands. Eoin O’Duffy of Monaghan had been seconded to the IRA GHQ staff and his deputy Dan Hogan had taken over as head of the Fifth Northern Division in Cavan, Monaghan and Leitrim. Frank Aiken of South Armagh commanded perhaps the most formidable guerrilla formation in the region, the Fourth Northern Division, based in counties Armagh, Down and Louth.

During the Truce period, the IRA were mostly engaged in organising training camps for existing and newly recruited Volunteers. There was an air of celebration about many such events; as the young IRA members basked in the popularity conferred on them by having apparently brought the British to the bargaining table.

At Killeshandra County Cavan for instance in November 1921, Sean MacEoin, commander of the IRA 1st Midland Division, recently released from prison, told the Volunteers, that he was ‘Proud to be in the field with the soldiers of Cavan… The young men have been called, “brainless, irresponsible, a murder gang”, but not anymore. Now they are recognised as men willing to sacrifice their all even life that their country might live.’[2]

The IRA used the truce period to reorganise and hold training camps

While the larger training camps were mostly located south of the prospective border,they were also set up in Northern territory. During the Truce a divisional training camp was organised at Killeavey near Newry, later there was also a company training camp at Ballymower in south Armagh.

Republican Courts were ordered to be set up around the country and the Irish Republican Police attempted to supplant the Royal Irish Constabulary as keepers of order. This was difficult even in the southern zone, where IRP officers attempting to carry out arrests were sometimes arrested by the RIC for false imprisonment and the Republican Courts broken up.[3]

But in the six counties of Northern Ireland, the enforcement of the republican ‘counter state’ was rarely possible. In Newtownhamilton, County Armagh, for instance, according to Edward Boyle, ‘due to our area being predominantly unionist, it was not feasible to set up properly constituted Republican Courts.’[4]

In some of the north, particularly in Belfast, the truce was more of a fiction than a reality. December 1921, for instance saw an outbreak of violence in Belfast, which the local nationalist press reported as, ‘an outbreak on the Catholics’, in which 18 were killed and 87 wounded. [5]

As a result, many IRA members along both sides of the border thought the truce was the prelude, not to a settlement, but to a further round of conflict, or Patrick Casey, an IRA officer from Newry, put it, ‘for the resumption of hostilities’ that would unify the country.[6]

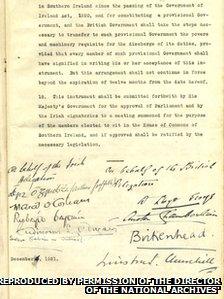

The Treaty

When the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed on 6 December 1921, most nationalists in border region supported it, but many of the IRA, particularly on the Northern side of the border, were less pleased. The Treaty not only disestablished the Irish Republic declared in 1919, in favour in the 26 counties, of the Irish Free State, a Dominion of the British Empire, but also all-but confirmed the partition of Ireland.

Northern Ireland was to be given the option of opting in or out of the Free State a year after the Treaty’s signing and Article Twelve stated that a Boundary Commission was to determine the shape of the border in Ireland, ‘in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants’.

For some republicans on the Northern side of the border there was anger at what appeared to be a meek acceptance of partition. Patrick Casey of Newry recalled ‘When we awoke the [Irish] ‘Independent’ [newspaper] had arrived and contained all details of the terms and signing of the Treaty. I remember well McKevitt, senior, saying that the terms were not a settlement and would lead to bloodshed. How true, in fact, were his words to become in the matter of a few months!’[7]

Most IRA leaders in the border region were persuaded to support the Treaty on the grounds that partition could be ended under its terms.

Most local IRA leaders, however, in the border area, notably Sean MacEoin of north Longford, Eoin O’Duffy of Monaghan and Paul Galligan of Cavan publicly came out in favour of the Treaty. Many, like O’Duffy expressed serious reservations in private about whether the Treaty would solidify the new border, but loyalty to IRA GHQ in Dublin and in particular to Michael Collins ensured their assent for the Treaty. [8]

In Dan Hogan’s IRA Fifth Northern Division in counties Cavan and Monaghan, there were some defections to the anti-Treatyites, but he, like his erstwhile chief Eoin O’Duffy, remained wedded to the leadership of Michael Collins and his promise that the Treaty would lead to an independent all-Ireland Republic.

Frank Aiken, the commander of the IRA Fourth Northern Division, which spanned both sides of the border, was against the acceptance of partition but was persuaded not to oppose the Treaty in public by Collins, who assured him that not only was partition temporary but the new Dublin government would support IRA military actions across the border.[9]

Part of Aiken’s command under Patrick McKenna did go along with the anti-Treaty IRA Executive which disavowed the authority of the Dail, the Provisional government and IRA GHQ in March 1922. Aiken, however, tried to remain aloof from the dispute and kept McKenna’s group within the Fourth Northern Division.

Collins told Northern IRA leaders in private that ‘partition would never be recognised even in meant the smashing of the Treaty’.[10] Many of his pro-Treaty officers such as Eoin O’Duffy continued to hold hardline stances against partition.

But more broadly, especially on the southern side, the initial reaction to the Treaty seems to have been one of relief. There would be a sovereign Irish state, with an Irish army and police. British forces would evacuate the territory of the Free State. All 3,600 Irish republican internees would be freed and a general amnesty was announced for all acts committed prior to the Truce.

The release of local prisoners (most of whom had been held in an internment camp at Ballykinlar, County Down) seems to have been a powerful local selling point for the Treaty. They were given heroes’ welcomes on their return to their home towns and villages in the next two weeks.

Civilian Pro-Treaty nationalists generally presented the Treaty merely as common sense, its defects only temporary. Joe McCarthy a Louth farmer, thought, ‘It gives us everything except Ulster and wise government and gentle economic pressures will induce Ulster to come in’. Most argued for the Treaty’s practical benefits; the end of hostilities and the departure of British forces As Sean Milroy in Cavan put it at a Pro-Treaty rally at Cootehill, ‘If you want the Black and Tans back again, smash up the Treaty’.[11]

Most local representative bodies therefore approved of the settlement and welcomed the Dail’s approval of the Treaty on January 14 1922. [12]

Unionist reaction to the Treaty was mostly negative, Unionist leader Edward Carson for one, denounced it as a surrender to ‘terrorism’, stating, ‘I never thought I would live to see a day of such abject humiliation for Great Britain.’[13]

But Northern unionists were particularly concerned with Article Twelve of the Treaty which allowed for a Boundary Commission which might redraw the border in the Free State’s favour. James Craig the new Northern Ireland premier, would write to Winston Churchill in May 1922 that the Boundary Commission was a destabilising factor, or as he put it, the ‘root of all evil’. ‘If you picture loyalists on the borderland being asked by us to hang on by the skin of their teeth for the safety of their province… [but] you may by the stroke of the pen take away the very area you now ask us to defend’.[14]

The Crown Forces depart the Free State

One of the first major results of the Treaty was the evacuation of the British Army and the disbandment of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) south of the border in the prospective Free State.

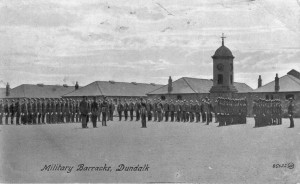

Military garrisons left Ballybay, Clones, Monaghan and Castleblayney early in February 1922 to be replaced by IRA garrisons. On February 11, the local press reported that the ‘Free State Army’ had taken over the barracks on Monaghan with ‘five Officers in uniform. ‘All bore arms’. It was ‘very imposing’ they reported and caused ‘great interest in the town’. On February 18 it was reported that 105 local IRA Volunteers had left for training and equipping at Beggar’s Bush Barracks in Dublin, central depot of the Free State’s new Army.[15]

As Crown forces departed in the spring of 1922, the IRA took over their posts and barracks on the southern side of the border

The departure of the RIC was somewhat more gradual. They were to initially set to stay in Swanlibar until disbanded in August 1922. In Ballyconnell, County Cavan the RIC reportedly handed hand back guns to unionists in the town, which had been collected in April of the previous year, before departing. The wartime ‘Black and Tan’ recruits were seen in civilian clothes, waiting for evacuation. For a period the RIC conducted joint patrols with the Irish Republican police. It was March before the RIC departed Cavan town. [16]

The largest military barracks in the region was at Dundalk. Early in April 1922, Frank Aiken’s IRA Fourth Northern Division occupied Dundalk barracks, moving their headquarters which had been in Newry, south of the border as the British forces evacuated the 26 counties. One of his men remembered, ‘In April 1922, Dundalk Military Barracks was occupied, mostly by men from [northern] Newry and Camlough Battalions and, in addition, armed camps were established at Ravensdale, Co. Louth, and in a few other areas in Co. Louth.’ [17]

The IRA garrison at Dundalk, in other words was largely composed of Northern Volunteers and, supplied by Michael Collins’ Provisional Government in Dublin, began furtively arming the IRA units in the North. Edward Boyle of Armagh, recorded a truck of arms arriving from Dundalk for the Ballymower company at Cooney’s farm and McLogans’ house. The latter dump was later, however captured by the Ulster Special Constabulary.

One of Aiken’s men outlined his political stance: ‘He [Aiken] preached the doctrine of complete disagreement [with the Treaty] on the one hand and justified (to himself) the taking over of the barracks [at Dundalk] as a base from which to launch attacks on the Six County area. Apparently, Aiken had received promises of almost unlimited supplies of arms to fully equip the Volunteers in the Northern area.’[18]

In the course of early 1922, significant numbers of southern IRA units, mostly anti-Treaty in sympathy, were also drafted into the border area, notably a contingent from Cork and Kerry. Southern IRA men, led by Cork officer Sean Lehane, were based in County Donegal, but there were also southern contingents along the border in County Cavan.[19]

Together, the Northern Divisions of the IRA and other IRA units in the border region numbered perhaps 4,000 men by 1922.[20]

It is unlikely that the pro-Treaty authorities, even Collins, the most hawkish of them, were thinking in terms of an overt military invasion of the North, especially given his government’s dependence on the British for arms and funds at this date. However, in the context of the still uncertain final shape of Northern Ireland, it seems likely that armed action was part of a range of measures contemplated, including also paying of Northern nationalist schoolteachers and county councils who refused to recognise the Northern government, to destabilise the Northern state and encourage the departure of much of its southern and western area to the Free State.

The Ulster Special Constabulary were tasked with defending the northern side of the border.

On the other side, the unionist government, led by James Craig, was determined to lose ‘not one inch’ of their territory and so they too mobilised their military resources along the border in early 1922.

This principally meant the 30,000 plus men of the Ulster Special Constabulary, recruited, in the main from Ulster Protestants but armed and uniformed by the British government. There were also the remnants of the RIC and the nascent Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), about 3,000 strong by March 1922. Up to thirteen battalions of regular British troops were also in Northern Ireland on stand-by if necessary, but under the command of the London government rather than the Northern Ireland authorities. Together, this amounted to up to 40,000 armed men in the uniform of the Crown on the Northern side of the border.[21]

It was the Special Constabulary that were given responsibility for securing the frontier. In County Leitrim, for example, when the IRA took over Ballinamore barracks, the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) occupied and fortified Drumshannuck House on other side of border.[22]

The Specials were from the start accused of heavy-handed treatment of nationalists and Catholics on the Northern side of the border. IRA member form Armagh, Edward Boyle, for instance, remembered the Specials raiding a Sinn Fein dance, shooting an IRA messenger outside and then beating the men there and forcing them to ‘go down on their knees and curse the Pope’. The Specials established a permanent base in that area at Synott’s Castle at Whitecross. [23]

Escalation

In these circumstances an outbreak of conflict along the border in early 1922 may have been inevitable. However, the actual escalation was occasioned by a series of mostly unplanned events.

The first was an attempted IRA raid to free prisoners in jail in Derry in late 1921. The raid failed, but resulted, inadvertently, in the death of two police warders, poisoned by chloroform, which had been intended merely to immobilise them. Three of the IRA party were sentenced to death by the Northern government. This in turn led to an attempt by Monaghan Volunteers under Dan Hogan, to break them out, travelling to Derry under cover of the Monaghan Gaelic football team. Hogan and ten of his men were arrested by the Northern authorities having been found armed in Derry city on January 14 1922. [24]

Inevitably this led to an IRA response, in which a secret Ulster Council, headed by Michael Collins himself, was set up to coordinate republican actions along the border. Their first major action in response to the arrest of Hogan was to authorise a large-scale incursion across the border on February 7-8 1922, in counties Tyrone and Fermanagh in which around 40 prominent unionists were seized and taken to southern territory to be held hostage for the reprieve of the Derry prisoners and the release of Dan Hogan.[25]

While some, such as historian Peter Hart, have argued that this was done on the initiative of local IRA commanders, Eoin O’Duffy, Sean MacEoin and others, this seems entirely unconvincing, given Collins close ties with and control over, these pro-Treaty commanders.[26]

On the level of high politics, these exchanges led to two ‘Pacts’ between Collins and Craig, brokered by the British in January and March 1922, which were supposed to, but failed, to keep the peace.

A series of unplanned events provoked an outbreak of hostilities along the border in February to March 1922.

At a more local level along the border though, the events of early 1922 led to an explosion of violence. Special Constables were flooded into the border area following the IRA hostage-taking and a party from the Belfast area, crossing by train into southern territory at Clones on February 11, came under fire in disputed circumstances from the local IRA unit.

According to the IRA, the twenty strong group of Special Constables ignored an order by a unit of eleven IRA men to surrender and opened fire themselves. The IRA returned fire with, among other weapons, a Thompson sub machine gun, raking the train. By the time the firing had stopped, five men were dead, including the IRA commander Matt Fitzpatrick, and four USC members, Sgt Doherty, Constables McMahon, Lewis and Abraham. Two were ‘critically wounded’ and thirteen more were wounded and captured by IRA. [27]

The so-called ‘Clones affray’ temporarily halted the British military evacuation from Ireland and local IRA commanders O’Duffy and MacEoin visited Clones and stated they ‘cannot guarantee peace until IRA Divisional Staff [including Dan Hogan] arrested in Derry is released’.[28]

Hogan and the Derry men were indeed reprieved by the British government and released by mid March. The unionists taken hostage in February were also mostly exchanged in March for republican prisoners, though some remained imprisoned for longer.

Looking only at the set-piece and relatively well known events such as the Clones incident, however, obscures a more localised pattern of low level violence along the border that did much to solidify the new frontier in 1922.

A low level war

For instance, an IRA party at Butlersbridge Cavan, while looking for arms, shot dead a blacksmith named Thomas Sadlier. In Monaghan, the IRA stopped the fox hunt (traditionally associated with the mostly Protestant landed gentry) at Carrickmacross in protest at threatened executions of IRA men in Derry. [29]

On the Northern side, two Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) patrols fired at each other accidentally at Kinawley Co. Fermanagh, killing one. In early March, it was reported that the USC had fired on workers crossing the border near Clones, wounding a civilian. The Specials also blocked and trenched roads leading over the border.[30] In other areas, for instance in Ballyconnell in Co. Cavan, barricades were erected at night on the northern side

‘Men who lived with each other in perfect harmony and ridiculed the idea of the border now see what partition has brought about’

By March 18 1922, the local paper, the Anglo-Celt, reported a veritable state of war. In a report titled ‘border tension’, they cited nightly firing across the border; ‘Armed men face each other rifle in hand.’ ‘Farmers will not till the land’. There is no trade across the border’. ‘Men who lived with each other in perfect harmony and ridiculed the idea of the border now see what partition has brought about’. [31]

Similarly it was reported that ‘Farm work is at a standstill’ at Emyvale Co Monaghan due to firing across the border.[32] Similar reports were received from Roslea, just over the border from Clones, where, the local paper reported, ‘people are in extreme dread of the Specials’.[33]

By March 25 they were reporting that bridges had been blown up along the Northern side of the border and there were ‘20 casualties in clashes’ between the IRA and USC. The IRA managed to assault and take a post at Belcoo on the northern side, taking its garrison of sixteen men prisoner and a clash on the border at Culloville in late March saw two Special constables killed and more wounded. [34]

The local press reported that ‘Threatening notices have been posted’ on both sides. Catholic families were crossing for safety from Tyrone and Fermanagh into County Monaghan, while Protestants from Glaslough, Monaghan, sought refuge inside Northern Ireland.[35]

Similarly, in County Donegal, on the western edge of the border, there were consistent raids across the border into Northern territory by both pro-Treaty troops – predominantly local Donegal men, and anti-Treaty elements largely composed of Munster IRA men and units from south Derry and Tyrone.

It is not entirely clear how much of the IRA activity was directed by local and national leaders, particularly as the organisation was at this time splintering over the Treaty. However, it does seem that much depended on local initiative and actions by one IRA unit may not always have been welcomed by another.

The travails of the Ballymower company from south Armagh for instance, gives us a window into the sometimes-chaotic conflict. On April 29, three prominent members of the IRA Ballymower Company were arrested by the Special Constabulary at Newtownhamilton fair. In retaliation their comrades raided and smashed up a local Orange Hall, shooting and wounding a local man, after which they decamped over the border to Co. Monaghan at Mullaghduff. From there, they had a three or four hour fire fight with the Specials, firing from a hill in Free State territory. There were no human casualties but both the IRA and the Specials took to shooting cattle on the other side of the border.

The following day there was more shooting and the IRA thought there were number of casualties among the Specials. The local pro-Treaty IRA commander, Peter Woods told the South Armagh men to ‘clear off out of Monaghan’ as they were ‘only causing trouble’. They raided a number of unionist owned businesses before leaving for an IRA camp at Bridge-a-Crine, Kilcurry, Co Louth, affiliated to Frank Aiken’s Fourth Northern Division. [36]

There was something of a lull in fighting along the border in April 1922 and even local truces were reported, for instance ‘at Belcoo/Blacklion, where ‘Both sides agree to punish unauthorized acts’.[37]

‘Belfast butchery’ and community relations

While the situation along the border in early 1922 was volatile and extremely disruptive, it was not terribly bloody. A rough count yields around 100 fatalities in the border region in the first six months of 1922.

According to Paddy Mulroe, about 90% of fatal casualties in the province of Ulster in the years 1920-23 took place in the city of Belfast, which according to Kieran Glennon’s figures included just short of 300 deaths in 1922.[38] According to Glennon, Catholics ‘accounted for 24% of the Belfast population in the 1911 Census, but 57% of those killed during the pogrom period – more than double their share of the city population’.[39]

Certainly, the nationalist perception of events in that city was of ‘a pogrom’ of innocent Catholics. The local press along the southern side of the border reacted to events such as the murder of the McMahon family in Belfast, reportedly by uniformed policemen, as ‘Belfast butchery’. ’Civilisation aghast’. [40]

Killings in Belfast greatly escalated tensions in border areas.

These and similar events embittered community relations along the border as much as those actually taking place there, and it put Protestants in southern territory, many of whom were former (or even current) unionists in a most difficult position. Many appeared to hold them responsible for the treatment of Catholics in Belfast.

At a meeting of Monaghan County Council in Clones in April, a Protestant member asked Catholics if they would be compelled to leave the county. They also discussed the fatal shooting of thirteen Protestants in West Cork (today known as the ‘Dunmanway massacre’ or ‘Bandon Valley murders’), the ‘use of revolvers’ in general and the ongoing killings in Belfast.

The Chairman Toal said he ‘Condemns both murders in Belfast and Cork’. ‘Everyone has the right to express their views according to their conscience’. Samuel Nixon (a unionist), stated that found Mr Toal’s ‘remarks very timely’ and that he ‘abhor[ed] all murders no matter by whom committed.’ However, another councillor, Ward, said that while events in Cork were ‘regrettable’, they were ‘down to the Belfast events’. ‘People will get out of hand’, he warned if local unionist did not disassociate themselves from events in Belfast he concluded: ‘Unionists must condemn the Belfast murders’.

Mr Knight, another unionist, responded ’I condemn all murder including the horrid system of reprisals in Belfast’ but pointed out that Drumully Parish School [Protestant] had been ‘burned to the ground’ near Clones. [41]

There seems to have been particular pressure felt by local Protestants to vocally condemn events in Belfast. On April 8, Protestant clergymen met in Carrickmacross and resolved to ‘condemn all murders and assassinations but especially the McMahon murders in Belfast’.[42]

Nevertheless, later that month, warnings were posted in in Clones; ‘To every Orangeman of the district. For every Catholic murdered in Belfast, two Orangemen will be killed in Monaghan’. Both pro and anti-Treaty IRA factions condemned the posters.[43]

Nationalists maintained, not always convincingly, that sectarianism in the conflict was all on the other side. According to the Anglo Celt, ‘On the Free State side, not one unionist family has been interfered with, Protestants enjoy peace and freedom’ But in Tyrone, they argued on the Northern side, ‘eight Catholic families have been expelled from their homes by the Specials’. Catholics had, they reported, been beaten, had their furniture thrown out in the street and been told to leave.[44]

The Northern Offensive

By April 1922, Michael Collins’ patience with Northern Ireland premier Craig, particularly with regard to the treatment of Catholics in Belfast, was at low ebb. He also attempted to reforge unity in the IRA by offering co-operation with the anti-Treatyites in actions in the North. And he probably also hoped that by taking physical control, in whole or in part, of areas of Northern Ireland, the Free State’s claim to them would be strengthened.

The manifestation of this was the ‘joint Northern offensive’ which Collins agreed with anti-Treaty forces on the north in May 1922, whereby both pro and anti-Treaty IRA units were to launch a concerted offensive on Northern Ireland in that month.

In order not to alert the British to Provisional Government involvement, a plan was devised to swap the weapons held by the anti-Treaty Four Courts garrison and some other Southern and Western IRA units, with British weapons given to the National Army and sending the former to the Northern units.

Both pro and anti-Treaty IRA units were involved in an abortive northern offensive in May 1922

The result was that British arms were delivered by the truckload to the Provisional Government’s anti-Treaty opponents in the Four Courts in Dublin and the latter’s weapons were sent to the north. Todd Andrews wrote, ‘I knew that lorry loads of arms were coming in from [pro-Treaty army headquarters] Beggars Bush to the Four Courts and that we were in return sending arms to Beggar’s Bush…It transpired that these were intended for an ‘Army of the North’.[45]

Anti-Treaty IRA units going to the border, for instance a contingent of Cork and Kerry men on their way to Donegal, were first briefed and armed in the Four Courts in Dublin. Mossy Donegan of Cork recalled, ‘We had plenty of rifles to spare… mines were also available. As a matter of fact, later on a lorry of mines parked in the Four Courts and ready to go north was blown up during the attack on the Courts.’[46]

The ‘northern offensive’, remains shrouded in some mystery. The plans for it have not survived in any detail, but recollections of them vary from a reasonably realistic plan of stepped up guerrilla warfare to an entirely unrealistic notion of IRA columns converging on Belfast in a conventional offensive. While the IRA could conceivably have taken and held nationalist majority areas along the border from the Special Constabulary, they had little hope in securing a hold over unionist majority districts and none at all of defeating the regular British Army in battle and marching on Belfast. [47]

In the event the proposed offensive was something of a fiasco. As Patrick Concannon has written, ‘none of the [pro-Treaty] IRA Northern Divisions based in the prospective Free State, the 1st, 4th and the 5th Northern Divisions, took an active part in the offensive.’ While the Northern based ones, mostly in Belfast and Derry ‘went ahead and took the brunt of the Northern state’s response’.[48]

Collins appears to have called off the offensive at the last minute, as far as the pro-Treaty units reporting to him were concerned. Numerous accounts particularly from Aiken’s Fourth Northern Division attest to this. Why this was so remains a matter for speculation, with some arguing that Collins was merely using the Northern issue to attempt re-unify the IRA in the south, or even that he hoped to deplete the anti-Treaty elements involved so that they could no longer challenge his government.

Another, perhaps more plausible theory, is that Collins was made aware that the British were aware of his plans and would not tolerate them. He also faced hostility from senior members of the Provisional Government including Arthur Griffith, who thought armed action in the North would collapse the Treaty settlement.[49]

But speculation on what did not happen along the border in May 1922 has to some extent obscured what did.

There were significant clashes along the Derry- Donegal border and in the south Armagh area between the IRA and the Special Constabulary at Jonesboro and Mullabawn. [50] On 3 June 1922, the IRA shot dead a Newry-based resident magistrate, James Woulfe Flanagan.[51]

The tail end of the offensive saw the largest military encounter along the border, at Pettigo along the Donegal-Tyone border. On May 27 the Special Constabulary attempted to oust the IRA (both pro and anti-Treaty units) from Maghermeena Castle but were forced to withdraw after clashes in which they took some losses of men and armoured vehicles. This left the IRA units in possession of the towns of Belleek and Pettigo, including parts on the Northern side of the border. Winston Churchill, under pressure from James Craig, who characterised the affair as an ’invasion’ of Northern territory, sent in the British military, supported by artillery and in a two day fight the IRA forces were driven back across the border with four killed and more wounded or captured.[52]

‘Nothing could justify it’

The period of the Northern offensive also saw some of the worst of the sectarian violence along the border.

Many Catholics and Nationalists fled Northern Ireland as the violence there worsened in May and June 1922. According to Michael O’Hanlon, of the Fourth Northern Division, ‘Dundalk and the whole countryside was full of refugees; houses were being burned in our area and across the border fellows were being shot dead. They [the Special Constabulary] took up the old men and shot them when we laid mines [in Northern Ireland]…so we were up against terror in Dundalk’.[53]

Occasionally Belfast refugees took revenge on unionists south of the border. On June 3 1922 it was reported that three men including Pat McGovern, a ‘refugee from Belfast’ were charged at Ballyconnell, County Cavan, with intimidation of Protestant Robert Crawford of Slieve Russell, whom they reportedly told to ‘go to the six counties’. [54]

May-June 1922 saw the worst of sectarian killing on both sides.

But the dynamic of sectarian reprisal also produced far bloodier results than this. In Desertmartin County Derry for instance, in revenge for the IRA killing of several local policemen, some of them in their beds, the Special Constables killed seven Catholic men in the locality.[55]

In the south Armagh/south Down area the Specials assassinated two Catholics near Camlough and sexually assaulted a woman, Una McGuill who was a Cumman na mBan member and the the wife of a Sinn Fein councillor.[56] It appears that Frank Aiken ordered, in retaliation, as well as an ambush of armed Specials at Dromintee, a savage assault on Protestant civilians in the Altnaveigh area of south Down, killing six civilians, one of them a woman, as well as burning over a dozen houses.[57]

Even some republicans were dismayed by the ferocity of the reprisal. One of Aiken’s men recalled, ‘I remember that my feeling at this reprisal was one of horror when I heard the details. Nothing could justify this holocaust of unfortunate Protestants. Neither youth nor age was spared and some of the killings took place in the presence of their families’[58].

Civil War

The Northern IRA Divisions were gravely weakened by the events of May 1922, with many hundreds fleeing south to avoid internment in its aftermath.

Nevertheless there would perhaps have been renewed hostilities along the border had not Civil War in the south intervened. On June 28 1922, the Provisional Government bombarded the anti-Treaty headquarters at the Four Courts in Dublin, bringing pro and anti-Treaty factions to blows around the country.

Within a month the IRA units along the border were fighting each other. In Donegal this had already happened to an extent where a shootout in Newtowncunningham in May had left four pro-Treaty solders dead. It was the Four Courts attack however, that prompted the final parting of the ways. Pro-Treaty units, which pre-dominated in counties Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan, rapidly secured those counties for the Dublin government.

The advent of Civil War in the south effectively ended the undeclared border war.

In July 1922 Frank Aiken, head of the Fourth Northern Division, who had tried to stay neutral, and many of his men were arrested by Dan Hogan, head of the pro-Treaty Fifth Northern Division and imprisoned in Dundalk. While Aiken himself escaped and a counter-attack by him and his men took the town of Dundalk and freed hundreds of republican prisoners in August 1922, it was the effective end of raids over the border.

Aiken himself later stated that as a result of the Civil War in the south, all action north of the border had to be called off. Anti-Treaty elements were now effectively outlaws on both sides of the border, compelled to fight not only the Northern government but the southern one too. [59]

The Provisional Government in Dublin, preoccupied by its own survival, diverted its attention from the North. Once Michael Collins, always the most outspoken member of government on the North, was killed at Beal na Blath in Cork on 22 August 1922 it also dropped many of his aggressive policies towards the six county area. In September 1922 the Government agreed that National Army soldiers should not cross the border under any circumstances when they were armed or in uniform.[60]

On the Northern side, the southern Civil War prompted a certain amount of relief. Northern Ireland Chief Secretary Wilfred Spender noted that ‘hold ups and looting have nearly ceased’. The conflict in Southern Ireland has drawn away many of the most active politicals from Ulster’.[61]

While Northern IRA Volunteers fought in the southern Civil War on both sides, many simply fell into bewildered inactivity. Edward Boyle, of the Armagh Ballymower company, stated that after participating in Aiken’s attack on Dundalk, they, went with a few others into the south Louth district and we remained there for some time. Later we went to Omeath and spent some time there. In or about October 1922, we got orders to move into Co. Cavan.[62]

Boyle for one tried to visit his home in South Armagh, now firmly across the new border and was arrested by the Special Constabulary. He was imprisoned in Belfast until 1924.

The border conflict of 1922 thus failed to resolve anything beyond hardening the frontier both physically and in the hearts and minds of the inhabitants of the region. While Northern unionists could perhaps claim some sort of victory, they also had ‘abandoned’ numbers of ‘their’ people in southern territory.

It was the summer of 1923 before most of the main cross-border routes were reopened to traffic. In the wake of the ceasefires north and south, the first July 12 Orange parade was held in Clones since 1920. At the Monaghan Orange rally, a leading Orangeman, Michael Knight, struck a conciliatory note stating that, ‘we are under a constitution which is not of our choice’, he stated but, ‘we form a considerable minority and a substantial interest.’ The Free State government’, he noted has promised to respects liberties and rights of minorities’.[63]

For Northern nationalists, however there was not even this comfort. If the ‘border war’ of 1922 had no clear winners, it certainly had a clear loser in the Northern Catholic minority.

References

[1] Anglo Celt, December 10, 1921

[2] Anglo Celt November 12, 1921

[3] See Anglo Celt November 17, 1921 IRP arrest youths for drunkenness at Carrickmacross fair. RIC arrest them Francis Keenan, Peter Corrigan.

3 IRA arrested in Court in Armagh for false imprisonment and holding illegal court at Castleblayney. Refused to recognise court. Cite breach of the truce.

[4] Edward Boyle BMH

[5] Anglo Celt December 10, 1921

[6] BMH WS 1148 Patrick J Casey IRA Newry

[7] BMH WS 1148 Patrick J Casey IRA Newry

[8] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy a Self-Made Hero, p88

[9] Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, the Irish Revolution 1916-1923, p115

[10] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish Civil War, p.79

[11] Anglo Celt February 25, 1922

[12] Anglo Celt December 1921, for the local Treaty debates, see John Dorney, The Treaty debates in the border counties.

[13] Anglo Celt Dec 10 1922

[14] Cited in Cormac Moore, Birth of the Border (2019), p.66

[15] Anglo Celt Feb 11, 18 1922

[16] Ibid.

[17] Edward Fullerton WS 890 Bureau of Military History (BMH)

[18] Patrick J Casey BMH WS 1148

[19] Kieran Glennon, From Pogrom to Civil War, Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA, (2012) p.145-146

[20] Moore, Birth of the Border, p.85

[21] Figures are from Winston Churchull in House of Commons, 21/3/1922, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1922-03-21/debates/979eefe4-b38b-40d7-b40d-509700d58ec1/Ireland My thanks to Paddy Mulroe for pointing this out.

[22] Anglo Celt Feb 18 1922

[23] Edward Boyle BMH

[24] Moore Birth of the Border, p.87-88

[25] Ibid. p88-89

[26] For Hart’s Argument see Peter Hart, Mich the Real Michael Collins, p.380-381. For the opposite view see Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, The Irish Revolution 1916-1923, p.119-120

[27] Anglo Celt February 18, 1922

[28] Anglo Celt February 18, 1922

[29] Anglo Celt Feb 9 1922

[30] Ibid March 9 1922

[31] Ibid March 18

[32] Ibid, April 1 1922

[33] Ibid March 18

[34] Ibid, March 28-29, the dead constables were Sgt Earley of Roscommon (presumably an ‘old RIC’ constable), Constable Harpar of Derry and Constable Dougald of Dungannon.

[35] Ibid.

[36] All above information on Ballymower company from Edward Boyle BMH

[37] Anglo Celt April 15, 1922

[38] Patrick Mulroe, Moving away from the Bandit Country Myth, published in Ireland and Partition, Context and Consequences, James Murphy, N.C. Flemming eds, (Clemson, 2021), for Belfast, Kieran Glennon, the Dead of the Belfast Pogrom Addendum, https://www.theirishstory.com/2022/01/20/the-dead-of-the-belfast-pogrom-addendum/

[39] Glennon Ibid.

[40] Anglo Celt April 1 1922

[41] Anglo Celt May 6 1922

[42] Anglo Celt April 8 1922

[43] Anglo Celt April 29 1922

[44] Anglo celt April 15 1922

[45] Andrews, Dublin Made Me, p238

[46] Glennon, Pogrom to Civil War, p 174

[47] For a discussion of the plans for the Northern offensive see Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War, p137-138

[48] Patrick Concannon, Michael Collins, Northern Ireland and the Northern Offensive, The Irish Story, https://www.theirishstory.com/2019/08/12/michael-collins-northern-ireland-and-the-northern-offensive-may-1922/

[49] Lewis, Frank Aiken’s War p. 140

[50] Ernie O’Malley interview John McCoy, ‘The Men Will Talk to Me’ Northern Divisions, Cormac O’Malley, Siobhra Aiken ed.s, p.163.

[51] Mulroe Myth of Bandit Country

[52] See Glennon From Pogrom to Civil War p180-181

[53] Michael O’Hanlon, ‘The Men Will Talk to Me’, p. 137.

[54] Anglo Celt 3 June 1922

[55] Moore, Birth of the Border, p. 100

[56] For discussion of this case see Linda Connolly, ‘To Remember the Civil War we must recall violence against women’ Irish Times, Jan 11 1922.

[57] Lewis, frank Aiken’s War, p. 150-154

[58] Patrick Casey BMH

[59] Submission in John McCoy’s Military Pension. MSPP34REF16473

[60] Cabinet Meeting 15 September 1922, Mulcahy Papers p7/B/245

[61] Cited in Moore, Birth of the Border, p.100

[62] Edward Boyle BMH

[63] Anglo Celt July 17 1923