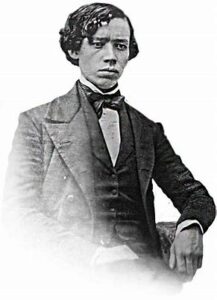

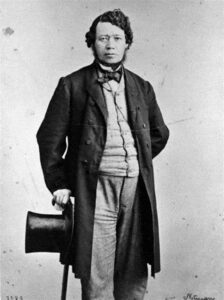

Thomas D’Arcy McGee – The Irish revolutionary who was one of the fathers of the Canadian Confederation

By John Joe McGinley

Thomas D’Arcy McGee was a journalist, author, poet, politician and Irish revolutionary, who is now recognised as one of the founding fathers of Canada. Despite his youthful radicalism, in later life, he became a staunch supporter of the British constitutional monarchy and parliamentary system. It was this dramatic shift in political views that led to his assassination in 1868 at just 43, at the hands of suspected Fenians.

The formation of a rebel heart

Thomas D’Arcy McGee was born on 13th April 1825 in Carlingford, County Louth. His mother Dorcas Catherine Morgan was the daughter of a Dublin bookseller who loved Celtic mythology and sympathised with the Irish struggle for independence from Britain. As a result, Thomas became versed in Irish culture and nationalism from a young age. His mother’s views heavily influenced his later writing and political activity.

He spent his early years at Cushendall on the north Antrim coast, where his father James worked for the Coast Guard Service.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee was born in County Louth but grew up in Antrim and Wexford, where he was schooled in the memory of the 1798 rebellion, before emigrating to America.

When he was eight years old, his father was transferred to Wexford, but tragedy was to strike when his mother was killed on 22nd August 1833, in an accident during their move to their new home.

The now motherless Thomas attended a local hedge school, where the teacher, Michael Donnelly fed his hunger for knowledge. Donnelly, whose father had been hanged at nearby New Ross after one of the bloodiest battles of the 1798 rebellion instilled in Thomas a deep nationalist spirit and a desire to oppose British rule in Ireland.

When Thomas was 14, inspired by a nationwide temperance movement, McGee published two poems in the local newspaper, both extolling the virtues of sobriety. This would be the first of many poems he would write throughout his life, most of which were not published until after his death.

In 1842 at age 17, McGee left Ireland for America with his sister due to a poor relationship with their new stepmother Margaret Dea, who had married his father in 1840.

They sailed from Wexford harbour aboard the Timber ship Leo to live with his mother’s sister in Providence, Rhode Island. After leaving his sister with his aunt, Thomas set out to find work.

The birth of an orator and writer

He eventually settled in Boston and began to make a name for himself almost immediately.

On the Fourth of July, American Independence Day, the fiery teenager gave a rousing speech to the Boston Friends of Ireland, blaming “a heartless, bigoted, despotic government” for the sufferings of the Irish. Ireland’s “people are born slaves,” he declared, “and bred in slavery from the cradle; they know not what freedom is.” (1)

In Boston, D’Arcy McGee became a firebrand orator in favour of Irish independence.

As a result of a passionate speech in Boston, the 17-year-old McGee was offered a job by Patrick Donahoe, editor of the Boston Pilot, the leading Catholic newspaper in New England.

Just two years later, he became a co-editor there. Writing for New England’s growing Irish community, McGee wrote articles on Irish literature and Irish nationalism, promoting the movement for Irish self-determination led by Daniel O’Connell, which was known as ‘Repeal of the Union’ or simply ‘Repeal’ and urging the Irish in America to support the movement in Ireland.

A passionate believer in the power of education Thomas was at the forefront of a campaign to establish evening schools for his fellow Irish immigrants.

Thomas also published his first two books: Eva MacDonald, a Tale of the United Irishmen (1844) and Historical Sketches of O’Connell and his Friends (1845).

Thomas also advocated the union of Canada with the United States, saying, “Either by purchase, conquest, or stipulation, Canada must be yielded by Great Britain to this Republic.” (2) This was a view that he would dramatically reverse in future years.

In May 1845, after a year as the sole Editor of the Pilot, McGee returned home to Dublin having been invited to work for the Freeman’s Journal, a popular daily newspaper, which supported Daniel O’Connell.

Back in Ireland

His first role for the Freeman’s Journal was as their parliamentary correspondent in London, although he became increasingly interested in literary history, publishing the Gallery of Irish Writers (1846) and A Memoir of the Life and Conquests of Art MacMurrogh (1847).

In 1847 Thomas married Mary Caffrey, and they would go on to have six children.

While covering parliamentary proceedings in London, he felt drawn to Young Ireland, a group of Irish intellectuals who were increasingly critical of O’Connell’s gradualist approach to independence and stated loyalty to the British monarch. McGee was asked to leave the Freeman’s Journal as a result of articles he wrote anonymously for the Young Ireland weekly, The Nation, and in April 1847 he officially joined The Nation.

He returned to Ireland in 1845 to work for the Freeman’s Journal, the leading nationalist newspaper but was sacked for his association with the radical paper, The Nation.

Meanwhile, increasingly alarmed about the worsening famine in Ireland, McGee opposed mass emigration to Canada, arguing instead that the government should ban grain exports and spend money on improving the economy. He denounced wholesale emigration as a “swindling speculation” concocted by the landlords, who to save their own skins were ready to see “2,000,000 Irishmen…banished into the Canadian backwoods.” (3)

At one point, McGee declared that the towns of Ireland had “become one universal poorhouse and fever-shed, the country one great graveyard.” The survivors of famine and pestilence had “fled to the sea-coast and embarked for America . . . and the ships that bore them have become sailing coffins, and carried them to a new world, indeed; not to America, but to eternity.” His allusion to “sailing coffins” gave rise to the term “coffin ships.” (4)

In Dublin, McGee became secretary of the Irish Confederation, a group of Young Irelanders who had split from Daniel O’Connell’s Repeal Association. By early 1848 divisions formed within this group also, with militants such as John Mitchel, and James Fintan Lalor, advocating a national insurrection, but McGee stood by the conservative leadership of William Smith O’Brien and Charles Gavan Duffy.

In February 1848, after the overthrow of the monarchy in France, the Irish Confederation began advocating armed rebellion. In highly this charged climate McGee was arrested for sedition in July, but soon released due to a lack of any concrete evidence against him.

The Irish Confederation was now on an unstoppable course towards insurrection, and in late July McGee was sent to Scotland, and later Sligo, to rouse sympathisers.

While in Edinburgh, a local newspaper proclaimed that authorities considered him one of “the two most dangerous men now abroad.” (5)

D’Arcy McGee had to flee Ireland after the failure of the 1848 rebellion, back to America

He returned to Ireland for the Young Ireland rebellion, which was quickly crushed at Ballingarry, Co. Tipperary, on 29th July.

The government was rounding up Young Irelanders, most of whom would soon be transported in chains to Van Diemen’s Land (today Tasmania). Dejected and now wanted by the authorities for treason, McGee made his way to the northern Irish coast, where he was protected by Dr Edward Maginn, the Catholic bishop of Derry. On September 1, 1848, disguised as a priest – and after arranging for his wife to follow –he boarded the Shamrock, a ship bound for Philadelphia.

In America once again

Thomas took time to visit his sister and aunt and then moved to New York City where he launched a new newspaper, The New York Nation. However, his editorials soon drew fire from the Roman Catholic hierarchy whom he denounced for refusing to support rebellion back in Ireland.

The Bishops in New York and many priests from the pulpit encouraged their parishioners to boycott the Nation. The New York Nation closed in early 1850 and Thomas Moved once again settling in Boston where he quickly set to work on launching another Newspaper the American Celt. He had learned his lesson in New York and moderated his criticism of the Church.

Thomas was a prolific writer. In the six years beginning in 1851, He published five books. covering the history of Irish settlers, revolutionary liberalism, the Protestant Reformation in Ireland, Catholics in North America, and the biography of the priest who had helped him escape to America, Bishop Edward Maginn.

In the summer of 1852, he moved his newspaper to Buffalo, New York and then into the city itself in 1853.

His newspaper sought to improve the lives of Irish emigrants by promoting schools for children, adult education and encouraging migration to rural areas.

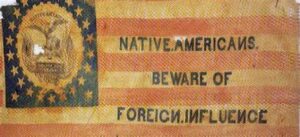

In New York a political force had arisen driven by hostility to the dramatic rise of Irish emigrants, this was known as the Know Nothings. The party was officially known as the “Native American Party” prior to 1855; thereafter, it was simply known as the “American Party”. Members of the movement were required to say “I know nothing” whenever they were asked about its specifics by outsiders, providing the group with its colloquial name. (6)

As he voiced opposition to what he perceived as racism from the Know Nothings against his fellow Irish, Thomas began to become increasingly disillusioned with the plight of the Irish diaspora in the Eastern seaboard of America.

In the US, D’Arcy McGee gradually grew disillusioned wit the growing anti-Catholic sentiment there and grew to advocate Irish settlement in Canada instead..

McGee and his paper became advocates for the creation of an Irish colony on the western frontier of America or Canada. This campaign earned him the nickname ‘Moses McGee’. (7)

He also began to become disillusioned with democracy, republicanism and the United States itself. Feeling it had failed him and his fellow Irish.

in 1856 he organised a conference in Buffalo New York with the aim of raising money to fund his idea.

Despite over 100 delegates attending, 43 of them from Canada, Thomas failed to raise enough money to fund a colony. Worse still, the Catholic Bishops began to mock his belief that perhaps Canada would be more tolerant to Irish Roman Catholics than America, arguing that political life there was dominated by the Orange Order – the all-Protestant (and frequently anti-Catholic) society founded in Ireland in the 1790s.

McGee however, in his writings was far more optimistic than the clergy, believing that the Orange Order in Canada was far more moderate and tolerant than its militant counterpart in Ireland. He wrote that it “is far more political than religious and I am assured by the most respectable Catholics in Canada West that they have no better neighbours than these same Orangemen.” (8)

It is debatable who was right; it is true that certain areas of Canada did have a strong and at times oppressive Orange Order planted from Ireland, spurned on by fear of rising Roman Catholic emigration. However, it has to be said that to ensure social cohesion and to avoid riots, the British administration was actively working to establish a framework for the accommodation of Catholics, especially in the Canadian east which was heavily populated with French and Irish Roman Catholics.

With this dream of a new Irish colony unfulfilled, Thomas now looked away from America to Canada and especially Quebec where Roman Catholics constituted a majority and had enjoyed legal protection since 1774. He also recanted his earlier suggestions that America should annex Canada.

After a series of visits to Canada, he concluded that minorities like the Irish would enjoy far more liberty and tolerance there than in America.

Canadian friends implored Thomas to move to Canada permanently telling him that the Irish there now needed bold political leaders.

A New life creatively and politically in Canada

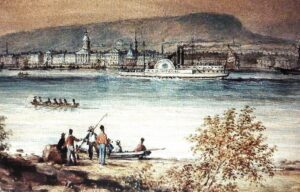

In 1857, McGee settled in Montreal where he set up a new publication called the New Era, which was a champion of creating a Canadian confederation.

In his editorials, McGee also attacked the Orange Order and defended Irish Catholic rights to political representation. He became an advocate for the federal union of British North America, westward expansion, and for the creation of national literature for Canada.

His vision was for a North American alternative to the United States but in stark contrast to his republican roots, one which would retain a close connection with Great Britain and the system of a constitutional monarchy.

In December 1857, just months after arriving in Montreal, Thomas was elected to the province of Canada’s assembly as a representative from Montreal. This meteoric political rise was due in large to the backing of the St Patrick’s Society of Montreal who threw their significant weight behind his campaign.

In 1857 D’Arcy McGee moved to Montreal where he was quickly elected as a representative and became a staunch supporter of Canadian nationhood

The Young Irelander now became a staunch supporter of Canadian nationhood and over the next decade his political views turned increasingly conservative, and he also became a firm believer in the virtues of parliamentary democracy.

Now at the centre of Canadian politics, he served in the moderate reform government but defected to the Conservatives in 1861 to campaign for and secure a bill for separate Catholic education. He also gained a law degree that year from McGill University in Montreal.

In 1863 McGee was appointed the minister for Agriculture, immigration and statistics. He also advocated that the planned intercontinental railway should extend not just from Central Canada to the pacific ocean but also to the Atlantic, winning friends in the West and East.

In time he served as a minister in Quebec and grew into a strong supporter of constitutional monarchy, both in Canada and Ireland.

He also wrote a series of letters and articles which promoted his belief in what he termed ‘new nationality’, a political association of British North America embodying many of the ideas of the more conservative Young Irelanders, which envisioned a political state presided over by one of Queen Victoria’s sons. He concluded Canadians had achieved a better balance between freedom and order than that which existed in the United States.

In September 1864, Thomas led a delegation to the Charlottetown Conference which gave birth to the idea of a confederation of Canadian provinces. Delegates from Prince Edward Island, the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick established basic principles for a political union of British North America.

Thomas used all his oratorical skills to promote the case for union and one delegate Charles Tupper who would go on to become the premier of Nova Scotia said of Thomas that:

“Mr. McGee has done more to promote the social, commercial, and political union of British North America than any other public man in these provinces.” (9)

As the momentum for union grew, politicians from the five British North American colonies gathered in Quebec City in October 1864 to continue discussing their unification into a single country. The most prominent issues decided in Quebec City were the structure of Parliament and the distribution of powers between the federal and provincial governments.

McGee’s most important contribution in Quebec was to successfully lobby to protect minority rights in education, moving an amendment to guarantee “the rights and privileges which the Protestant or Catholic minority in both Canadas may profess as to their denominational schools.” (10)

In 1865 Thomas was now free to visit Ireland as he had been pardoned for his part in the earlier rebellion. It was here that his political transformation from a radical young Irelander to a staunch supporter of parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy was completed.

Visiting his old home in Wexford he gave a speech where he first urged anyone thinking of emigration to consider Canada rather than the United States. He then began to attack the Fenian Brotherhood which advocated an invasion of Canada from the United States. He also urged nationalists in Ireland to follow the Canadian model of self-government within the British Empire. He even denounced his own revolutionary activities as being “the follies of one and twenty”. (11)

The speech was reported widely back in Canada, and he was denounced by many of his previous supporters. Many of his fellow Irish even labelled him a traitor and he was expelled from the St Patrick’s Society.

McGee’s support amongst the Irish community that he had so long sought to protect was now ebbing away just as his long-held dream of a Canadian Confederation became a reality in July 1867.

Despite this McGee still had sufficient support to be elected to the first Canadian national parliament as a liberal-conservative representing Montreal West. Having lost most of his Irish Roman Catholic support, a disillusioned McGee made it known he would quit politics at the next election to devote time to his family and writing. Canadian Prime Minister John MacDonald informed him he would receive a civil service position as a reward for his support and work in helping achieve Canadian Union.

Assassination

However, McGee would not enjoy a peaceful retirement. on the 7th of April 1868, Thomas spoke in a debate that dragged on past midnight. When he left the Ottawa Parliament building, he walked to his boarding house. As he opened the door to his room, he was killed by a shot to the head from an assailant who was waiting inside.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee’s popularity had certainly declined by the time of his assassination. However, his funeral brought an unprecedented crowd into the streets of Montreal.

Held on what would have been his 43rd birthday on April 13th, 1868, the funeral attracted tens of thousands of people and he was remembered all across the new Canadian Confederation that he had done so much to nurture and establish.

The Aftermath

The authorities suspected a Fenian conspiracy and acting on information supplied by an informer swiftly arrested Patrick James Whelan an Irish immigrant from Galway.

Whelan was arrested at his boarding house and during a search the police discovered membership cards of Irish Canadian Fenian organizations and a Smith & Wesson revolver that they believed had been fired the previous day.

In custody, Whelan continued to plead his innocence but the evidence against him grew.

Several witnesses came forward that testified Whelan had bragged about assassinating McGee on a number of occasions. Others claimed he had made threatening gestures to McGee from the visitor’s gallery in the Canadian House of Commons.

A detective with the Grand Trunk Railway, Reuben Wade, claimed that he had overheard Whelan and a group of conspirators plotting to kill McGee. Meanwhile, a policeman and a fellow prisoner who were eavesdropping near his prison cell reported that Whelan bragged about what a “great fellow” he was for shooting McGee. (12)

D’Arcy McGee was shot dead by s Fenian sympathiser in 1868

However, the most damning evidence was the claim by a Mr Jean-Baptiste Lacroix that he had seen Whelan shoot McGee.

Despite still vehemently claiming his innocence, by the time Whelan’s trial date was set the prosecution was certain of a guilty verdict.

Whelan maintained his innocence throughout his trial and was never proven to be a Fenian. Nonetheless, he was convicted of murder and hanged before more than 5,000 onlookers in Ottawa on 11th February 1869.

Many have argued Whelan’s innocence, but forensic tests conducted in 1973 indicated that the fatal bullet was compatible with both the gun and the bullets that Whelan owned. (The bullet that killed McGee was found lodged in the door frame of his room) (13)

Although Whelan denied that he was the hit man, he said just before his death that he knew the identity of the killer and that he was present when McGee was assassinated. This of course would have made him guilty as an accessory to the murder of the man who had done so much to help create the Canadian nation.

Sources:

- Gerber, David A. (1989). The making of an American pluralism: Buffalo, New York, 1825–60. University of Illinois Press. p. 157

- Demeter, Richard (1997). Irish America: The Historical Travel Guide. Vol. I: United States, Northern Atlantic States, District of Columbia, Great Lakes Region and Canada. Cranford Press. p. 535

- Thomas D’Arcy McGee | The Canadian Encyclopaedia

- Thomas D’Arcy McGee | The Canadian Encyclopaedia

- Boylan, Henry (1998). A Dictionary of Irish Biography (3rd ed.). Gill and MacMillan. p. 246

- Boissoneault, Lorraine. “How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics”. Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- Thomas D’Arcy McGee | The Canadian Encyclopaedia

- Thomas D’Arcy McGee | The Canadian Encyclopaedia

- Thomas D’Arcy McGee – Irish Biography (libraryireland.com)

- Wilson, David A. (2011). Thomas D’Arcy McGee: Volume 2: The Extreme Moderate, 1857–1868. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Wilson, David A. (2011). Thomas D’Arcy McGee: Volume 2: The Extreme Moderate, 1857–1868. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Wilson, David A. (2015). “The assassination of Thomas Darcy McGee

- Wilson, David A. (2015). “The assassination of Thomas Darcy McGee