Did Michael Collins order the killing of Henry Wilson?

By Ronan McGreevy

The assassination of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson MP was an event that I have called Ireland’s Sarajevo. Just as the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand was the triggering event which led to the First World War, the Irish Civil War would not have happened the way it did without the Wilson shooting.

The significance of the Wilson assassination has often been underplayed in Irish histography because the assumption that the Civil War would have happened anyway. This would presume that the pro and anti-Treaty sides had made plans for war. Neither had done so.

There was much talk of war, but this very talk paralysed people against its eventuality. IRA commander Florrie O’Donoghue remembered: ‘Despite six months of the talk of the possibility of civil war no one had allowed himself to believe it to be inevitable and no plans existed on either side for conducting it.’ [1]

Henry Wilson’s assassination was ‘Ireland’s Sarajevo’

The anti-Treaty rebels, which had occupied the Four Courts from April 1922, had not even taken the precaution of digging a tunnel under the complex. Even while they were being surrounded by National Army troops, they were reluctant to make the first move. ‘The [Free] Staters were taking advantage of the fact that we did not want to open fire on them. We were like rats in a trap,’ Ernie O’Malley recalled in his posthumously published memoir The Singing Flame. [2]

Fatal Timing

Wilson was assassinated on the doorstep of his own home at 36 Eaton Place in London on June 22nd, 1922. The timing of the killing was exceptionally unfortunate. It happened just six days after the general election of June 16th, 1922 in which pro or Treaty-neutral candidates got 78 per cent of the vote.

The final results of that election had only filtered through – Michael Collins was in Cork dealing with an allegation of electoral fraud – when the Wilson shooting happened.

Had it happened before the general election it is unlikely the provisional government – which had no electoral mandate – would have taken the drastic steps to use British guns to shell the Four Courts. Had the shooting happened at a distance of some time after the election, it could have coincided with attempts by pro and anti-Treaty Sinn Féin to put together a post-electoral government though that would have been a violation of the Treaty.

The British ultimatum following Wilson’s killing triggered the onset of Civil War in Ireland

The two sides had, after all, agreed a pre-electoral pact to put forward candidates in proportion to their respective strengths in the pre-election Dáil. There was talk of an inner cabinet of Treaty-supporting ministers with an outer cabinet of those who were anti-Treaty. All of this is in the realm of counterfactual history as the Wilson shooting and the British ultimatum which followed moved the trajectory immediately away from politics and towards civil war.

There were a number within the cabinet, Arthur Griffith and Kevin O’Higgins among them, who were in favour before the Wilson shooting of a military confrontation with the anti-Treaty garrison in the Four Courts, but the unanimity that would have been needed for such a momentous decision would not have occurred without the British ultimatum.

The timing of the outbreak was fortunate from the Free State perspective as the anti-Treaty IRA had a numerical advantage, but did not have time to organise against the National Army.

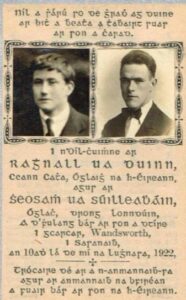

Dunne and O’Sullivan: ‘good soldiers and Catholic Irishmen’

There is no doubt as to who killed Wilson. His assassins, Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan, were two London-born injured veterans of the Great War turned radicalised Irish nationalists and members of both the IRA and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). O’Sullivan had lost a leg at Passchendaele in 1917.

Given their evident disabilities – Dunne walked with a limp from a knee injury – they had embarked effectively on a suicide mission when they shot Wilson dead on the doorstep of his own home on June 22nd 1922. They were quickly apprehended by an angry mob, tried and executed on August 10th of that year.

There has been much unnecessary speculation over the years as to why they shot Wilson. The answer is in the statement given by Dunne and O’Sullivan and published in The Irish Independent on August 12th, two days after they were hanged.

Who was Sir Henry Wilson? What was his policy, and what did he stand for? “You have all read in the newspapers lately, and been told, that he was a great British Field Marshal; but his activities in other fields are unknown to the bulk of the British public. The nation to which we have the honour to belong, the Irish nation, knows him, not so much as the great British Field Marshal, but as the man behind what is known in Ireland as the Orange Terror. He was at the time of his death the military advisor to what is colloquially called the Ulster Government, and as military advisor he raised and organised a body of men known as the Ulster Special Constabulary, who are the principal agents in his campaign of terrorism.” [3]

This statement contradicts the often repeated theory that Wilson was shot as a result of an order delivered by Michael Collins before the Truce of July 1921 to assassinate him, but not acted upon. Wilson only became military adviser to the Northern Government in March 1922.

Who, therefore, ordered Wilson to be assassinated? This question has been one of the enduring mysteries of Irish history for the last 100 years.

The most commonly advanced theory is that Dunne and O’Sullivan acted of their own accord. This was the conclusion of Rex Taylor’s flawed account, Assassination, published in 1961. [4]

He based his theory on a letter allegedly sent to Denis Kelleher by Dunne from jail. Kelleher was a Cork-born IRA volunteer who lived in London and was supposed to have been the getaway driver on the day of the Wilson assassination, but did not turn up.

IRA members Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan said they killed Wilson because ‘he was the man behind what is known in Ireland as the Orange Terror’

In a letter from prison Dunne allegedly told Kelleher that they had gone to Eaton Place just to barrack and insult Wilson, not to kill him. For all they knew he might not turn up. As Wilson got out of the car, O’Sullivan, inexplicably to Dunne and without orders from his more senior officer, shot Wilson, and so the disaster for the pair began. The absence of an able-bodied accomplice or a getaway driver demonstrated that murder had not been on the mind of the pair when they killed Wilson. Taylor’s claim, which suggested that Dunne had sought to blame O’Sullivan for the shooting, enraged O’Sullivan’s family.

More seriously still, Taylor did not produce the letter that Dunne had allegedly sent to Kelleher. In a letter to the Irish Press in 1968 Frank Lee commented: “The individual concerned [Rex Taylor] has been challenged several times by Joe O’Sullivan’s brother, Pat, to produce this remarkable document, but has failed to do so.”[5]

In his 1992 analysis of the shooting, the late historian Peter Hart concluded there was “no solid evidence” to suggest that anybody else had ordered the shooting and therefore:

“We must accept the assertions of the murderers that they acted alone, in the (grossly mistaken) belief that Wilson was responsible for Catholic murders in Belfast. My own hypothesis as to Dunne and O’Sullivan’s motives cannot be definitely proved, but it fits not only with what we know of them and the London IRA and IRB but also with the general anarchy and proliferation of revenge killings in Ireland at the time”[6]

Yet Dunne in his statement, which was published in the Irish Independent two days after his death, never stated that he and O’Sullivan had acted of their own accord in killing Wilson. Hart was implying from Dunne’s statement that they acted on their own, but Dunne remained silent on the issue. Dunne wrote the letter to whomever was going to be his successor in the London IRA, and it was smuggled out by Pat O’Sullivan. He was not going to commit to paper who had ordered him to carry out such a high-profile assassination.

Dunne and O’Sullivan were British soldiers before they joined the IRA. They understood the importance of the chain of command and of military discipline. In his extant correspondence, Dunne makes reference to discipline in his last letter to his father. “You and I must not grouse when it comes to enduring discipline because we are good soldiers and Catholic Irishmen.” He does so again in his letter to Rory O’Connor, when he praises the virtues of “strict discipline, secrecy, cheerful obedience to orders and punctuality”.

There is no evidence of either Dunne or O’Sullivan having been involved in maverick operations as IRA operatives. Everything they did in their IRA careers followed instructions from GHQ. This was particularly the case in relation to the assassination plans which were mooted during the conscription crisis of 1918 and during the hunger strike of Terence MacSwiney in the autumn of 1920. Dunne and O’Sullivan were privy to the moves to assassinate high-ranking British personages and knew that these orders were issued from GHQ. They were intelligent men who knew the gravity of what they had been asked to do.

In the immediate aftermath of the Wilson shooting, the British government blamed the anti-Treaty side, hence the ultimatum, but there is no evidence whatsoever that they were involved.

Who gave the order?

Who therefore gave them the order to shoot Wilson? It could not have been the Provisional Government who knew nothing about the shooting and had enough problems of their own. Neither could it have been the IRA though, somewhat confusingly, Dunne was the officer commanding the IRA in London. That order would have had to come from the chief-of-staff Richard Mulcahy who was horrified by the shooting and offered to resign.

There was only one figure in Irish nationalism at the time capable of giving an order to shoot dead a serving MP and a man, until February 1922, had been the professional head of the British army. That figure was Michael Collins.

Why would Michael Collins want Wilson dead? Why, having famously said that he had ‘signed his own death warrant’ in signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty, would he risk everything by having Wilson assassinated?

I did not know the answers to these questions before I started my book, ‘Great Hatred’ but in retrospect Collins’ motivations were hiding in plain sight.

Michael Collins was the only figure capable of ordering such an assassination and his motivations become apparent in the context of events in Northern Ireland at that time.

Wilson was a despised figure in Irish nationalism. He played a significant role behind the scenes in the Curragh crisis of March 1914 earning the enmity of the British prime minister Herbert Asquith in the process. He was the chief of the imperial general staff (CIGS) during the War of Independence and was publicly blamed for the execution of Kevin Barry though he had actually advised against it. Though born in Longford, he hated Irish nationalism. He was described by Florrie O’Donoghue as the “most fanatically anti-Irish Irishman”. [7].

As Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Wilson was critical of aspects of British counter-insurgency policy in Ireland in 1919-21, but advocated military defeat of the ‘rebels’ and was adamantly opposed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty which he characterised as a surrender to ‘terrorism’.

He was blamed, as the Northern military adviser, unfairly, as it turns out, for the anti-Catholic ‘pogroms’ in the North carried out by loyalists, often with the aid of the security forces of the new Northern state. Privately, Wilson despaired of the sectarian nature of the violence in the North and believed that the Catholic population had to be brought into the security apparatus if the new state was going to survive, but his public pronouncements were at odds with his nuanced private position on security matters.

Shortly after his election, unopposed, as Ulster Unionist MP for North Down, Wilson embarked on a series of furious speeches across Great Britain decrying the Treaty settlement and exhorting the British government to reconquer the South. Collins and Arthur Griffith were in the Distinguished Visitors Gallery in the House of Commons on May 31st, 1922 when they heard Wilson say:

“I do not think it wise in the face of the enemy to disclose these facts, but if serious trouble arises on the frontier between the six counties and the twenty-six counties, I hope that the Government will not restrain the military from crossing the frontier in their own self-defence.” [8]

In a speech in Wexford in April 1922 Collins said: “We all know only too well the hopes and aims of the Orange North-East Ulster. They are well expressed to the world with a lightly veiled brutality in the language of Sir Henry Wilson. They want their ascendancy restored. They want the British back. British diehards and the mischief makers of the Sir Henry Wilson breed are leaving no stone unturned to restore British domination in Ireland.” [9]

At the time, little attention was paid to this speech. It was part of the inflammatory rhetoric on all sides occasioned by the disturbances in Ulster. Collins made other comments about Wilson in public, describing him as a “violent Orange partisan”.[10] The actions of the British army at Belleek and Pettigo in early June 1922 may have been the event which finally convinced Collins that Wilson was a dangerous enemy who should be killed.

A mixed force of National Army and anti-Treaty IRA volunteers occupied all of Pettigo on the Donegal/Fermanagh border and the village of Belleek in Co Fermanagh in contravention of the Treaty, after a firefight with the Ulster Special Constabulary in which the latter were beaten off.

Winston Churchill, the Colonial Secretary, then in charge of British government policy in Ireland, was incensed and ordered the British army into the area with heavy artillery and a thousand men. It was overkill, but intentionally so. Churchill wanted to teach Collins the lesson that no Free State adventurism across the border would be tolerated and to placate the Northern premier Sir James Craig

On 4 June the British took Pettigo using howitzers to shell the Irish garrison guarding the bridge, which marked the boundary between the two jurisdictions. Three IRA volunteers manning a machine-gun nest were killed. The British occupied Pettigo until January 1923.

The battle, the last time British and Irish armies faced off against each other, is largely forgotten now, but it caused profound angst on both sides of the border at the time. Although Wilson had nothing to do with the use of British forces, he was blamed for it. The actions of the British army in invading and holding Free State territory was regarded as a provocation resulting from Wilson’s talk of re-invasion.

Collins thought as much and concluded, as a result of the Belleek/Pettigo incident that Wilson had a “Morning Post attitude to Ireland” referring to a newspaper notorious for its reactionary imperialism. [11]

Collins believed the Pettigo incident was intended to “deflect world attention from the worse than Armenian atrocities that are a daily occurrence in Belfast . . . in this design they were largely assisted by certain powerful British influencers and unconsciously by some of our own people.” [12]

Those searching for Collins’s motivation for ordering the shooting may need look no further than these statements. Seen from Collins’s perspective, Wilson provided the impetus for the Craig government’s ferocious crackdown on the IRA. If Wilson’s words were not in themselves enough to damn him as a formidable enemy, those of Sir James Craig were.

At his speech in the Northern parliament announcing Wilson’s role as a military advisor, Craig said he had put aside £2 million to justify their pledge to Wilson to do everything he asked in his advice to them as to how to respond to the security threat. “There was no better man to deal with the IRA. I would say if any man can devise means to meet these hordes of IRA and promoters of rebellion, that man is Sir Henry Wilson.”[13]

In order to understand Collins’ possible culpability in the shooting of Wilson, one has to understand that he was not just the chairman of the Provisional Government and therefore a public figure. He was also the president of the secretive Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

As Tim Pat Coogan said:

“There is a tendency on the part of some contemporary historians to ascribe Collins’s Northern policy merely to his desire to keep the South’s Republicans in line. But it went deeper than that. Collins was not only the head of the newly formed twenty-six-county Irish State. He was the head of the IRB, committed by conviction and by the oath administered to him by Sam Maguire to continue what was begun in 1916.”[14]

There were many in the Provisional Government who thought a secret society like the IRB had no place in a democratic state, but the statesman Collins found it hard to shake off the secret-society leader Collins.

There is no “smoking gun” proving that Collins ordered the assassination of Wilson, but there is a compelling case based on a multiplicity of accounts that he was ultimately responsible for that deed.

Collins had ample reason to want Wilson dead, but you will search in vain for any paper trail of the assassinations that he ordered. Given the frequent raids on IRA premises, leaving any such evidence would have been foolhardy. Instructions to the men who shot fourteen British agents on Bloody Sunday 1920 were given orally to members of the Squad and the Dublin Brigade. Such a modus operandi would be understandable in the context of a guerrilla campaign with a better resourced enemy, but Collins was the chair of the Provisional Government set up under the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Collins delegated the details to people he trusted to carry out assassinations in an efficient manner. In the case of the Wilson shooting, if he did order it, he may have trusted too much. Had he been aware of the details of what was planned for the shooting, he would certainly have objected to one of the assassins being a man with one leg and the pair being without a getaway car.

Collins might have believed he could get away with it. He did get away with it in the sense that the British government blamed the anti-Treaty rebels, but he did not get away with in the way that he anticipated.

Collins might have calculated that a well-planned ‘job’, the favourite euphemism of the IRA, would have seen the assassins escape. The Provisional Government could issue a plausible and honest denial, along with a resounding denunciation of this wicked crime. After all, most of the cabinet would have had nothing to do with it. Publicly, the British government would share the indignation of the public about the shooting of so distinguished a soldier. Privately, Collins might have believed they would not have been displeased that so vocal a critic was gone, along with his increasingly outdated views on Ireland and the Empire.

A compelling case

There is no incriminating document, no “smoking gun” that would prove beyond all reasonable doubt that Collins ordered the assassination of Wilson, but a book is not a court of law and I believe I have made a compelling case based on a multiplicity of accounts that he was ultimately responsible for that deed.

There is no incriminating document, no “smoking gun” that would prove beyond all reasonable doubt that Collins ordered the assassination of Wilson, but a book is not a court of law and I believe I have made a compelling case based on a multiplicity of accounts that he was ultimately responsible for that deed.

Certainly many of his contemporaries had no doubt. Joe Dolan, one of Collins’s Squad attached to the intelligence department of the pro-Treaty IRA GHQ and also his aide-de-camp, wrote to the Sunday Press in 1953 during a ferocious debate on whether or not Dunne and O’Sullivan had acted alone. Dolan wrote matter-of-factly: “This execution was ordered by Michael Collins because Sir Henry Wilson was the originator of the pogroms in the North in 1922.” [15]

Reflecting on the shooting almost thirty years later, Patrick Sarsfield (P. S.) O’Hegarty, a former member of the IRB Supreme Council, said Collins had given Sam Maguire the go-ahead for the shooting albeit at a time when Collins was under the utmost strain. [16]

In November 1966 the Irish Ministry of Foreign Affairs turned down an opportunity to stage military funerals for Dunne and O’Sullivan when their remains were to be returned to Ireland with one official stating that the “assassination of Wilson was carried out at the behest of Michael Collins at a time when his mind was virtually unhinged”. [17]

However, if this was the case, Collins made a tragically fatal mistake both for himself and for Ireland. The Wilson shooting laid bare the exasperation of the British government with the Provisional Government’s reluctance to deal with the anti-Treaty rebels occupying the Four Courts. The Wilson shooting gave the British a casus belli to demand the removal of the Four Courts garrison thus precipitating the Civil War.

Sadly the shots that killed Wilson would lead on two months to the day to the tragic death of Collins at Beal na Bláth.

Ronan McGreevy is a journalist with The Irish Times. The paperback version of Great Hatred: The Assassination of Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, published by Faber & Faber, is out now priced €11.99. His book, The Kidnapping, which he co-authored with Tommy Conlon, about the kidnapping of Don Tidey will be published by Sandycove in October priced €15.99

References

[1] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish Civil War, (Dublin, 2004), p.182

[2] Ernie OMalley, The Singing Flame, Anvil Press, Dublin 1992, p.93

[3] Irish Independent, August 12th, 1922

[4] Rex Taylor, Assassination: The Death of Sir Henry Wilson and the Tragedy of Ireland, (Michigan, 1961), p.132

[5] Irish Press, 25 June 1968.

[6] Peter Hart, ‘Michael Collins and the Assassination of Sir Henry Wilson’, Irish Historical Studies, vol. 28, no. 110 (Nov. 1992), p. 170

[7] Florence O’Donoghue, No Other Law, (Dublin, 1954), p.255

[8] Hansard, House of Commons debates, 31 May 1922, vol 50 cc884-908

[9] Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins: The Man Who Made Ireland (Dublin 2002), p.334

[10] The Times, 24 March 1922

[11] Belfast Newsletter, 10 June, 1922.

[12] Belfast Newsletter, 12 June, 1922

[13] Cork Examiner, 15 March 1922

[14] Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins: The Man Who Made Ireland (Dublin 2002), p.341

[15] Rex Taylor, Assassination: The Death of Sir Henry Wilson and the Tragedy of Ireland, (Michigan, 1961), p.211

[16] Irish Military Archives/Bureau of Military History, WS897, Patrick Sarsfield (P. S.) O’Hegarty, 1953

[17] Irish National Archives (DFA/10/2/484)