Nixie Boran and Communism in interwar Ireland

By John Dorney

Nicholas ‘Nixie’ Boran was born in coal mining area of rural County Kilkenny in the early twentieth century, and became an Irish republican, communist and trade union activist.

His story, though very unusual, reveals an interesting window into radical politics in the early years of the independent Irish state.

Nicholas ‘Nixie’ Boran, early life

Nicholas Boran was born in Muneenroe, Castlecomer in 1904, the son of a farmer and coal carter, George Boran and Mary Boran (nee Maher) who died in 1908. Nicholas was educated at the local National School in Castlecomer and subsequently by the Presentation Brothers in Castletown County Laois.

The 1911 census shows him at age 7, living in the family farm on Moneenroe, with his father, two grandparents in their 80s, three siblings and another relative. [1]

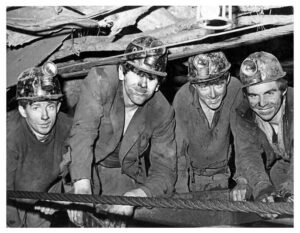

In 1918, aged 15, ‘Nixie’ returned to Castlecomer and began working in the coal mines, gunning a tram in the mine at Modubeagh Colliery – in other words hauling coal by tram from the coal face to collection points. [2]

There are numerous accounts that tell of Boran’s participation in the Irish independence struggle from 1919-1923, but few archival records. For instance he is not listed as having been a member of the local IRA companies in Kilkenny, nor does he have a state Military Pension file or a prison record.

However, he did participate in the Civil War of 1922-1923 on the side of the anti-Treaty IRA. According to Anne Boran, his daughter, he joined the Free State or Nationals Army’s 25th infantry battalion, stationed in Clonmel, but later deserted to the anti-Treaty IRA. He was apparently captured in the Glen of Aherlow County Tipperary and imprisoned at Clonmel jail. [3]

His arrest is recorded in National Army records. The Limerick Command reported on 10 May 1923, that troops had swept the Glen of Aherlow, a common guerrilla refuge both in the War of Independence and Civil War. Many arrests were made, including ‘Nicholas Boran of Castlcomer Co Kilkenny’. ‘Boran was in possession of one rifle and 55 rds .303 [ammunition]. The Army reported. ‘He is believed to be a deserter from the Army.’[4]

Nicholas Boran, a coal miner from Kilkenny, narrowly escaped execution during the Irish Civil War.

One version has it that he was imprisoned at Limerick, but gave a false name, only to be rescued by legendary south Tipperary men IRA men Dan Breen and Dinny Lacey. However a more plausible account, is that he was captured and sentenced to death for desertion, in a court martial in July 1923 but escaped from Emmet Barracks in Clonmel. He was on the run until the general amnesty of December 1924.

After the Civil War, ‘Nixie’ travelled back and forth between Dublin, the UK and also at some stage found work at the Skehana mines in Castlecomer. In 1927 Boran returned again to Castlecomer for good and got work in the Deerpark colliery – the most modern of the pits around Castlecomer, which opened in 1924.

Life would not have been easy for a young miner, who was also politically persona non grata, having been on the losing side of the Civil War and who was still active in the illegal IRA.

Nixie Boran appears to have been on the left wing of the post-Civil War IRA, close to republican socialist Peadar O’Donnell, and in 1931, Boran was elected onto the executive of Saor Eire, an IRA front group, intended to form the basis of political party, which espoused socialism as well as united, independent Ireland.[5]

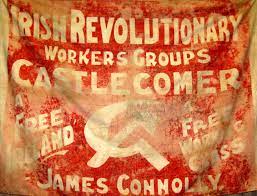

Saor Eire was both condemned by the Catholic Church and quickly banned by the Free State government. In the early 1930s Boran drew close to a new far left group, the Revolutionary Workers Group and tried to agitate in the County Kilkenny coal mines for better conditions as well as to politicise the miners.

To put this in context this requires a short digression into the small communist movement in Ireland in the 1920s and 1930s.

Communism in Ireland 1921-1939

The first Communist Party of Ireland was founded by executed 1916 Rising leader James Connolly’s son, Roddy. Roddy Connolly visited the young Soviet Union in July 1920, attended the second congress of the Communist International (or ‘Comintern’) and met Soviet leader V.I. Lenin personally. The instructions he was given for the small Socialist Party of Ireland (founded 1917) was to ally with Irish Republicans in their fight against British rule.[6]

Just over a year later, Roddy Connolly was given permission by Moscow to found the first Communist Party of Ireland (CPI) in October 1921. They had about 50 activists. During the Irish Civil War 1922-23, the Irish communists allied with the anti-Treaty IRA and 12 were imprisoned for fighting against the Free State.

Despite their small numbers they had some influence on republican IRA prisoners, including, famously Liam Mellows, later executed, whose notes out of Mountjoy prison argued for the republicans adopting the goal of a Workers’ Republic. [7]

Another such was Nixie Boran, whose left-wing politics seem to date from this time.

The Communist International attempted twice to establish a Moscow affiliated party in interwar Ireland.

The following year however, Roddy Connolly’s Communist Party was ordered by the Comintern in Moscow to dissolve. They hoped instead that James Larkin, the famous Irish labour leader, who had voiced his support for the Russian revolution and wanted to affiliate to the Comintern, would be their representative in Ireland through his own organisation the Irish Workers’ League. [8]

However Larkin proved disappointing to the communists, his Irish Workers’ League never really developing into a large movement and Larkin proving altogether too independent minded for Moscow. By the late 1920s Larkin had drifted back towards the Labour Party and the Comintern began to look for other avenues to exploit in Ireland. For a time, they appear to have hoped to move the IRA in socialist direction.

The IRA had, for purely pragmatic reasons, accepted covert funding from the Soviet Union in the early 1920s, in return for gathering intelligence for them, but towards the end of that decade the left wing of the organisation also began to make some political headway. The Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy warned in 1931 that there was a ‘concrete link’ between the IRA and communism, via the front group Saor Eire and ‘if the Soviet comrades are not dealt with, the state will perish’.[9]

Boran was attracted to communism via the left wing of the IRA, of which he was member until the early 1930s.

Saor Eire advocated nationalising the banks and the ‘means of production’. [10] Dan Bryan of the military intelligence section G2, commented that it was ‘interesting that the communist section are permeating other groups’. While in the Civil War period a ‘small communist party existed … [but] yet it was hardly able to hold together and exist… [but now] ‘at least in Dublin seems to be fairly successful in getting all extremist sections to accept its views… [whereas] formerly they were purely “national”.[11] But in truth the left wing faction in the IRA were a minority and they dropped the Saor Eire project almost immediately after it was condemned by the Catholic clergy in 1931. In 1933 the organisation formally disavowed communism.[12]

Parallel, however, a purely communist party was reemerging in Ireland. In 1927, the Comintern invited Irish socialists to study in Moscow at the International Lenin School. In 1929, James Larkin cut his ties with Moscow and the following year at the instigation of the Communist Party of Great Britain, a new group was formed in Ireland; the Revolutionary Workers’ Group, of which Nixie Boran became a member, alongside about 340 others. At least 30 were, like him, former IRA men. The RWG would later develop into a second Communist Party of Ireland, formally adopting that name in 1933. Its newspaper was the Workers’ Voice. [13]

Though there were also other tendencies in it – the RWG also made some headway in 1930s Belfast among Protestant workers – the fusion of Irish republicanism and socialism, borne out of the post Civil War environment was to prove an enduring feature of the Irish far left.

Boran’s visit to Moscow 1930 and return to Castlecomer

It was against this background in which the international communist moment was attempting to get an affiliate in Ireland back up and running, that Nixie Boran visited Moscow in August 1930.

Despite being denied a passport, he was smuggled to Russia aboard a cement ship and in August 1930, attended the Profintern or International of Red (i.e. communist) Trade Unions.

Boran visited the USSR in 1930 and came back a convinced communist.

In all he spent three months in the Soviet Union and visited the coal mines in the Donbass region (today in Ukraine but partly under Russian control since early 2014) and collective farms in Samara. This was during Stalin’s policy of forced collectivisation of agriculture – in which all peasant land holdings were confiscated by the state – though Boran was likely shown only model collective farms and not any of collectivisation’s destructive effects. [14]

Collectivisation and the ensuing famine, mostly in Ukraine, but also in Kazahkstan and elsewhere, in fact cost up to five million lives throughout the Soviet Union. But at the time, communist activists elsewhere in the world largely perceived it as a great success.

He also met some of the 20 Irish students at the Lenin School in Moscow.

There are many accounts of his return home to Castlecomer. He was arrested by the Gardai and taken for questioning but was also given a hero’s welcome by the miners, who gathered outside the Garda barracks until he was released. [15]

Founds the miners’ union and the 1932 strike

Back in Ireland, Boran was determined to found a militant union in the mines in and around Castlecomer. There was some presence of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) in the mines at the time but not much activity since a failed strike in 1926.

In late 1930 Boran invited the Scottish communist miner’s leader Bob Stewart to Castlecomer to advise the setting up of a new union and in December of that year founded the Irish Mines and Quarries Union, which was openly affiliated to the international communist movement. In February 1931, he also founded a branch of the Revolutionary Workers Group in Castlecomer.

He stated that his policy was ‘class against class, workers versus capitalism with its ultimate ambition the overthrow of the capitalist system’.[16]

Boran founded his own miners’ union that split with the Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union in 1931.

The first branch of the new union was founded in January 1931, when Boran led 30 miners out of the ITGWU and a second branch of 13 members was founded in Ballyragget pit in February. [17]

Outside of his own members however, Boran clearly had a following among the 450 or so miners at Castlecomer as he was elected ‘chuckweighman’ shortly afterwards. The chuckweighman had to verify the company’s figures of the amount of coal produced each month as it was on this basis that miners were paid. The Wandesfordes, the landed family who had own the mines since the 17th century as well as much of the land around Castlecomer, were alarmed, as was the local Catholic Church. [18]

In 1932, tensions further heightened in the mine as a recession hit and some miners were put on a two day week. Another grievance was that the miners had to buy low quality coal to keep warm, while tonnes of unsold ‘A grade’ coal lay stored in the coal yards in Castlecomer. [19]

In October 1932, Boran called a strike, calling for a pay rise, and calling the Wandesforde family (whose presence dated back to the 17th century Cromwellian plantation) ‘the enemy’ in both class and nationalistic terms, testament to the republican influence on communist rhetoric in Ireland.

He wrote in the Workers Voice ‘The enemy is an imperialist mine owner, a planter for whom Castlecomer is but an economic pocket borough, he owns every sod of it’. [20]

During the strike, the Dublin Trades Council refused to support the strikers as their union was not affiliated to the Trade Union Congress, but the miners did receive some support from left wing republican leader Peadar O’Donnell, who arranged for bread from some Dublin bakeries to be delivered to the miners and their families and wrote in their support in the IRA newspaper an Phoblacht. Eventually, the miners secured a small pay increase, brokered with the company by local Labour and Fianna Fail TDs. After a strike of about a month, the miners went back to work in November 1932. [21]

However, in the longer term Boran was forced into retreat from his ideal of an openly communist union.

Red Scare

As mentioned above, clerical denunciation had put paid to the Saor Eire initiative in 1931.

The Catholic clergy repeatedly denounced Boran’s union. On his return from Russia in 1930 the local priest Fr. Cavanagh alleged that he was paid with ‘red gold’ and that the Workers Voice was the ‘voice of the devil’. In 1932 Boran was accused of ‘trying to instil in the workers the teachings of Lenin and Trotsky’.[22]

There followed a long running war of words between Boran and the Catholic clergy in the local and national press. In Kilkenny city, a Dominican, Fr Ambrose, organised a series of talks on the evils of communism, including its suppression of Catholicism in Russia.

Among the guests he invited were a Russian princess who had been exiled by the revolution. Boran denied that there were any prison camps in the USSR and that he had not seen any on his trip there in 1930. He also brought to Kilkenny British Communist Party MP Shapuri Saklatvala to speak about anti-imperialism. [23]

Fr. Coleman retorted that Boran and his colleagues were given a false impression of the USSR on their three month visit and this was cleverly done by the Soviets to ‘make communists of these practically illiterate or semi-literate men who have little knowledge and no real power of judgement’. [24]

The Revolutionry Workers’ Group and Boran in particular were bitterly denounced by the Catholic clergy.

In 1932, during the strike at the colliery, the clergy forbade Boran’s union to use the parish hall, though it had been built partly due to donations from the miners, prompting Boran to build his own hall. The Catholic Church grew increasingly alarmed by Boran’s militancy and in 1932, the Bishop of Ossory, Collier, denounced the Revolutionary Workers Group as ‘agents of the devil’.

In January of the following year, this was followed up with a pastoral letter from the Bishop forbidding Catholics from joining either the Revolutionary Workers Group or the Miners’ Union;

‘Wherefore it is my duty to tell my people plainly that the Revolutionary Workers Group and also all and every union, cell or “contact” which is communistic in its object has come under the ban and censure of the Church. No Catholic may be or remain a member of such unions, no matter what name they may adopt. Also, no Catholic may buy, sell, read, receive or support any communistic literature journal or newspaper such as the Workers’ Voice.’[25]

He urged the miners at Castlecomer to re-join the ITGWU, ‘‘Enrol then in your lawful trade unions, strengthen your organisation, by every lawful means, work for your betterment within the law of God and the law of the State.’ He encouraged workers to work ‘slowly but surely’ towards the Catholic goal of ‘a living wage’… ‘My condemnation has no reference whatever to the main body of labour in this county … which carry on their good work within the laws of God and of the state. These have always had and will continue to have, the support, blessing and sympathy of the Church’.[26]

Bishop Collier also visited Moneenroe (Boran’s home townland) and preached of the evils of communism. After mass he held a ceremony in which the congregation was asked to renew their baptismal vows, with him asking ‘Do you renounce Satan and all his works’ and the congregation assenting. It was, by implication, also a renouncing of the Revolutionary Workers Group and the Miners Union. [27]

At a series of local meetings in the parish of Clogh, the locals also passed resolutions condemning ‘communistic teachings’, which was approvingly reported in the Kilkenny Journal.

In its time the Church had also denounced the ITGWU, notably in the Lockout of 1913, but it had learned since then, that it could accommodate even militant trade unionism within its flock, provided that it lacked a political, particularly communist or anti-clerical element. In 1933, the Bishop of Ossory opened a path to reconciliation with Boran and his colleagues, as long as they abandoned communism, by stating that his goal was ‘not to hurt, but to heal’ and appealed to ‘communist leaders’ ‘who are Catholics and Irishmen’ to ‘abandon such dangerous organisations which can only lead to the utter ruin of soul and body.’ [28]

As a result of social and Church pressure, by 1933, Boran had to backtrack. His union re-affiliated to the ITGWU as a miners’ branch of the wider union and renounced its affiliation with the international communist movement. Boran became chairman of the ITGWU miners’ branch in 1935.

As for the RWG, which was renamed the Communist Party of Ireland in 1933, it fared no better following the transition from the government of pro-Treaty Cumman na nGaedheal to Eamon de Valera’s Fianna Fail in 1932. De Valera’s government, for example, had Jimmy Gralton, like Boran a former IRA man turned left-winger, deported to America in 1933, where had been born, despite the fact that he was an Irish citizen.[29] In Dublin after the Party was denounced by the Archbishop at the Catholic pro-Cathedral, a mob marched to its headquarters at Connolly House and attempted to sack it. [30]

Against this background, neither communism nor left republicanism could gain a foothold in interwar Ireland.

While this was effectively the end of Boran’s political ambitions, he was able to secure some material improvements for the workers a chairman of the ITGWU miners’ branch. Baths, for instance were introduced to colliery at Castlecomer for this first time in 1949, as were facilities for drying clothes. [31]

The Strike of 1949

During the Second World War in Ireland, coal imports were greatly reduced and production at the collieries in Castlecomer had to be stepped up. This gave the workers some bargaining power and short strikes in 1940 and 1943 resulted in some pay increases.

Nixie Boran abandoned communism but not trade unionism.

However, this was only a preview of the longest and most bitter strike at the Kilkenny mines, which took place in 1949. The cause of the strike was the nature of pay for miners. Previously, pay had been linked to the market price for coal, but after the war, the Wandesfordes attempted to freeze pay at a standard rate, despite the fact that the price of coal was going up.

In March 1949, the 411 miners at the Deerpark colliery went on strike for better wages and a return to the pre-war system of pay.

Boran and his colleagues accused the Wandesfordes of being ‘an English company, which does not take into account the dignity and independence of Irishmen.’ A company initiative to bus in ‘scab worker’ to break the strike seems to have caused much acrimony locally.

Finally in February 1950, the miners returned to work, with a small pay increase. [32]

Closure of the mines and becoming a director

One of the great paradoxes of Nixie Boran’s life is that he finished his career, which had largely been spent fighting the Wandesfordes, by sitting alongside them as a director of the mining company.

Relations between the miners and management at the Castlecomer mines seem to have improved in the 1950s and 1960s. Nixie Boran devoted his energies to securing compensation for miners who had suffered from lung diseases as a result of working in the pits.

However, by the mid 1960s, the Irish coal mines were losing money and surveys taken showed that the amount of coal remaining was uneconomic to mine. In July 1965, the Deerpark Colliery closed, at a cost of 340 jobs.

Boran campaigned for the mine to re-open and had a report commissioned by the ITGWU, arguing that more reserves of coal had yet to be found there. In November 1965, the Irish government the Wandesfordes and the union put together a new company which re-opened the pit with a reduced workforce. Boran sat on the board of directors as the workers’ representative.

However, despite his efforts the mine finally closed for good in January 1969.

Nixie Boran died in 1972. Today one of the only physical reminders of the mine is a plaque at a statue of the Virgin Mary, erected by the miners, near the entrance to the pit which is also inscribed ‘to the memory of their deceased leader, Nicholas Boran, RIP.’[33]

Nicholas Boran was a singular individual and is still today something of a folk hero in the old coal mining country around Castlecomer. His story is not in any way representative either of the young men of his generation who fought in the Irish revolutionary period or of the Irish left. He navigated his own path. But his story is nevertheless testament to wider themes in twentieth century Irish history, the fusion of national and social discontent in Irish republicanism, the extraordinary moral power of the Catholic Church in independent Ireland and failure of the far left to strike deep roots.

References

[1] 1911 Census http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1911/Kilkenny/Moneenroe/Moneenroe/566282/

[2] Dictionary of Irish Biography p661-663, by William Nolan

[3] Nolan in Dictionary of Irish biography).

[4] Reports to Exec Council 4 IE/MA-CREC-04

[5] See Tim Pat Coogan, the IRA, p.59

[6] Charlie McGuire, Roddy Connolly and the Struggle for Socialism in Ireland, p.34.

[7] McGuire, Roddy Connolly, p72-88

[8] McGuire, Roddy Connolly, p.100

[9] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, p.182

[10] Adrian Hoare, In Green and red, the lives of Frank Ryan, 2004 p.68

[11] John Regan, the Irish Counter Revolution, p.288

[12] Emmet O’Connor, Reds and the Green, Ireland Russia and the Communist International 1919-1943 P.3

[13] Emmet O’Connor, Reds and the Green, Ireland Russia and the Communist International 1919-1943, p.3.

[14] O’Connor, Reds and Green p.156

[15] Source http://www.sip.ie/sip019B/history/boran.htm

[16] Nolan, Boran entry in Dictionary of Irish Biography

[17] O’Connor, Reds and the Green, p.162

[18] Nolan, Boran entry in Dictionary of Irish Biography.

[19] Joe and Seamus Walsh, In the Shadow of the Mines, p.14-16

[20] Nolan, Boran entry in Dictionary of Irish Biography.

[21] Walsh, in the Shadow of the Mines, p14-16.

[22] Kilkenny Journal, Nov 12 1932

[23] Matt Treacy, The Communist Party of Ireland 1921-2011, p.37.

[24] Anna Brennan and William Nolan, Nixie Boran and the Colliery Community of North Kilkenny

[25] Kilkenny Journal, January 7, 1933

[26] Ibid.

[27] Walsh, In the Shadow of the Mines, p.19

[28] Kilkenny Journal Jan 7 1933

[29] Hoare, Frank Ryan, p103.

[30] Ibid. p.105-106

[31] Nolan, Boran entry in Dictionary of Irish Biography.

[32] Anna Brennan and William Nolan, Nixie Boran and the Colliery Community of North Kilkenny.

[33] Anna Brennan and William Nolan, Nixie Boran and the Colliery Community of North Kilkenny