The Tunnellers of Mountjoy,1923

By Christopher Lee.

By Christopher Lee.

In 1923, after days of heavy rain the ground around the Mountjoy Prison blocks became sodden. An armoured car drove into the prison yard but suddenly its front wheels sank completely up to their axels, having caved in the roof of a tunnel that had taken Republican prisoners five months to dig.

Or, at least that’s the story told within the Brennan family.

I first became interested in the story of an escape tunnel being dug in Mountjoy Prison while I was researching the activities of Francis ‘Terry’ Brennan of Finglas during the War of Independence and Civil War. During the War of Independence, he had been a member of “B” Company, 3rd Batt., Fingal Brigade. Later, during the Civil War he had joined the 1st Brigade, 1st Eastern Division, and been part of the “Leixlip Flying Column”, under the command of Patrick Mullaney.

Capture at Leixlip

They carried out a campaign of sabotage and ambush in Kildare, as well as being part of an abortive attack on Baldonnel aerodrome and Lucan barracks. However, on 1st December, 1922, after carrying out an ambush near Pikes Bridge, Kildare, they were pursued across country by a much larger force of Free State soldiers which included an armoured car. After a long cross country running gun battle, they were eventually surrounded and forced to surrender.

Following their capture, the members of the column were taken to Kilmainham Jail and on 11th December 1922 were put on trial. The members of the Flying Column, including Francis Brennan, where found guilty of the charge of taking up arms against the state and were sentenced to death by firing squad. The flying column had also included five former Free State soldiers who were found guilty of being deserters and of committing an act of treachery. They were executed by firing squad at Beggars Bush Barracks on 8th January 1923.

However, due to a legal technicality the death sentences for the remaining members of the Flying Column were never carried out. As a result, their sentences were commuted to imprisonment and on 30th January 1923 Francis and the remaining members of the Flying Column were transferred to Mountjoy Prison. He remained there until 18th October 1923 when he was transferred to Tintown Internment Camp 2 and was released 17th November 1923.

The first mention of the Mountjoy escape tunnel that I encountered was in Francis’ obituary, which in part said:

One of the biggest escape tunnels ever undertaken was begun in Terry Brennan’s cell. It took five months to complete. In the course of these operations heavy rains flooded the cells and the prisoners had no place to sleep. This led to the hunger strike declared by Mr Sean Lemass. Mr Brennan was on this hunger strike for 22 days.

Within the Brennan family the story is that Francis was involved in digging a tunnel from his cell in Mountjoy but that it collapsed when an armoured car which was driving through the prison yard drove over it. Heavy rain had apparently softened the ground and the weight of the armoured car was enough to collapse it leading to the tunnel’s discovery.

This is the same story told within William Wyse’s family, who was another member of the Leixlip Flying column and who was in Mountjoy with Francis. But neither the obituary nor family stories gave any indication of when this happened or where they were tunnelling from or to.

As such, to check the facts behind the story and to satisfy my own curiosity I set out to see if there was any truth in it. So, in this short article I will attempt to address three aspects of the story – was there a tunnel that matched the one described in the obituary, is there any evidence that Francis Brennan was involved, and what was the likely destination of the tunnel.

Escapes from Mountjoy

The initial difficulty was that there were actually several different tunnelling attempts, both into, and within Mountjoy itself. One of the first mentions of tunnelling near Mountjoy is from 1922 when an attempt to tunnel into Mountjoy was discover.

On 14 July the house at 28 Glengarriff Parade was raided and Sean MacEntee and 12 others were arrested when a tunnel “several yards long” was discovered.[1] Glengarriff Parade runs along the eastern boundary of Mountjoy with the backs of some houses only twenty meters or so from the perimeter wall, separated from it by a ‘cordon sanitaire’, a cleared area around 30ft (10m) wide.

On 19 January 1923, another tunnel was discovered in the house at 30 Glengarriff Parade, only two doors away from the first attempt. This time the tunnel had progressed much further and was around ’70 feet long’ long or ’25 yards’. [2]

“…the point where the excavating was begun and the prison is not more than 27 yards, so that if the tunnel was 25 yards long it was within 2 yards of its objective when discovered. Probably another night’s work and it would have been possible to walk through the new thoroughfare in and out of the prison.”[3]

However, both of these were attempts to tunnel into Mountjoy from the outside whereas Francis’ tunnel was started within the prison.

On 20 October 1923 there is mention of a tunnel within an airshaft within Mountjoy to allowed access between upper and lower floors of a prison wing but it was discovered before work had progressed very far.[4]

However, on 31st October 1923 the following statement was read in the Dail Eireann by General Mulcahy:

“…steps taken to control prisoners’ movements in the prison have been such as effectively to stop work on a tunnel, upon which, it would appear, they had been engaged. This tunnel was found in an examination on the 17th October. It had been carried over a distance of 70 yards and would probably have been completed in another ten days”.

A tunnel of 70 yards (64m) is a substantial undertaking and would be consistent with the scale and duration of the tunnel mentioned in Francis’ obituary. A tunnel of 210ft or 64m is possibly still the longest escape tunnel in Ireland, significantly longer than any of the escape tunnels in the Maze Prison during the 1970s, the longest of which was about 41m or 44 yards[5].

So, the statement by General Mulcahy allows us to be sure that a large escape tunnel existed within Mountjoy at a time when Francis was imprisoned there.

The next question to consider is the matter of Francis’ involvement, if any, in its construction. Based upon circumstantial evidence I think there is a good chance we can say that Francis was integrally involved in working on the tunnel. His obituary states that the tunnel started from his cell, suggesting he likely had a basement level cell.

Through a stroke of luck, we have Francis Brennan’s inscription in the autograph book of Thomas McCann, another member of the Leixlip Flying Column, in which he notes that he is in ‘C’ Wing. William Wyse also signed Thomas McCann’s autograph book, also indicating he was in the same wing. The prison records held by the Military Archives, though incomplete, also indicate that at least one other member of the column was also in ‘C’ Wing. Interestingly, in Ernie O’Malley’s interview with Paddy Mullaney, the former commander of the flying column mentioned the following regarding John Gaynor, yet another member of the flying column:

“He was in charge of the Lewis gun which we had got from Baldonnel the day we were captured. Gaynor is in Clonsilla and O’Neill knows where he lives. He was a pupil of mine in school. He was always in the tunnels in the Joy, always trying to get out.”[6]

So, between Brennan, Wyse and Gaynor we have at least three members of the flying column involved in tunnelling.

But I think the strongest piece of circumstantial evidence that Francis was involved is the fact that he was transferred from Mountjoy to Tintown 2 the day after the tunnel was discovered. This could indicate that not only did the tunnel start in his cell but that he was identified as one of the ringleaders of the attempt. Interestingly, William Wyse and at least two other members of the Flying Column were also transferred on the same day. Perhaps the tunnel was an initiative of the members of the flying column, a tight knit group who had been members of one of the last operational Republican units in Kildare and Co. Dublin.

The final question to consider is what the objective of the tunnel may have been. To address this, we should first familiarise ourselves with the layout of Mountjoy Prison.

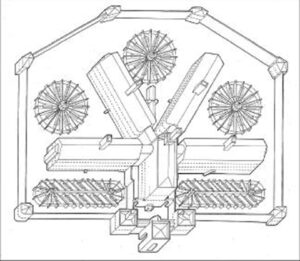

Constructed in 1850 it was built on a radial plan with four wings. Facing the prison gate, the left-hand wing is “A” wing, lettered clockwise, with “D” Wing the closest to Glengarriff Parade. It was built on a very similar layout to that of Pentonville Prison in London, both having been designed by the same man. In 1923, there were significantly fewer buildings currently crowd into the perimeter of the prison and the four cell blocks would have been surrounded by open space and fenced exercise yards.

Measuring roughly 70 yards (64m) from the North East corner of “C” Wing would place the tunnel head outside the perimeter wall on Glengarriff Parade but within the thirty-foot wide ‘cordon sanitaire’ that separated the backs of the houses from the prison wall. The statement by General Mulcahy indicated the tunnel was still ten days away from completion suggesting that merely getting outside the perimeter wall wasn’t the main objective.

Francis’s obituary says the tunnel took five months to excavate allowing us to make a rough calculation that they were progressing at around 40cm per day. If tunnelling continued at the same rate, ten more days would have placed the tunnel head within the backyards of the houses on Glengarriff Parade, potentially providing cover for an escape attempt.

It would seem highly unlikely the tunnel would have been directed North, towards the perimeter wall along the Royal Canal, a distance of around 82 yards or 90m. At a rate of around 40cm per day there is no way the tunnellers could have covered the remaining 23 yards (26m) in ten days.

Unfortunately, I have been unable to verify the part of the story about the tunnel being discovered when it was caved in by an armoured car. However, it is not implausible that, while the tunnel may have started out sufficiently deep, it might have crept closer to the surface over its length rendering it more vulnerable to being caved in.

However, despite that, we can say with some degree of certainty that the tunnel described in Francis’ obituary did exist and that he was in the right place at the right time to have been involved in its construction.

Perhaps, in the end, some of the details aren’t as important as the fact that it’s just a good story.

References

[1] The Evening Herald, 14 Jul. 1922, p.2

[2] The Irish Independent, 22 Jan. 1923, p.5

[3] Sunday Independent, 21 Jan., 1923, p.1

[4] Belfast Newsletter, 20 Oct. 1923, p.7

[5] Murtagh, T., The Maze Prison, Waterside Press, 2018, p.180

[6] Ernie O’Malley Notebooks, P17b