Book Review: The Irish Defence Forces, 1922-2022

By Eoin Kinsella,

By Eoin Kinsella,

Published by: Four Courts Press, (2023),

360 pp.

ISBN: 9781801510363

Reviewer: Jack Kavanagh

Eoin Kinsella’s study of the Irish Defence Forces provides a much-needed official history that spans the first century of the Defence Forces. As this book is essentially an institutional history and was the subject to a public contract with the Department of Defence, it should not be judged the same as an academic study based upon a masters or doctoral thesis.

It is unusual that this is only the third history of the Defence Forces that spans the full history of the Irish Defence Forces and it remains the only history to cover the period post-2000. Similar histories of the Irish Defence Forces include J.P. Duggan’s A history of the Irish Army (1991) and Eunan O’Halpin’s Defending Ireland: the Irish state and its enemies since 1922 (1999).

The book is divided into eight chapters and a series of brief timeline notes on Commanders in Chief and Chiefs of Staff for the Defence Forces, Ministers for Defence and Secretaries-General of the Department of Defence.

The text of each chapter is interspersed with reproduced photographs, memoranda, maps and other military ephemera such as posters. This highlights the rich material culture available on the Defence Forces from the 1920s onwards.

Each chapter is also supplemented by subsections focusing upon a specific theme or area within the Defence Forces. For example, the specialist corps during the Irish civil war, cartoons in An t-Óglách and the creation of the Defence Forces School of Music.

The Army saw the height of its political influence at its foundation in 1923-24, but thereafter it was kept small and relatively starved of funds.

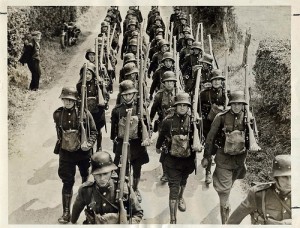

The first three chapters examine the period 1922-39, with the significant focus upon the first decade of the Irish Free State. During this period, the nascent Irish Free State underwent a series of significant military, political, societal and constitutional changes which Kinsella addresses from the perspective of the Defence Forces. The military, having grown to a strength of nearly 60,000 in order to fight the Civil War, reached an apex of power in 1923-4 and was thereafter to play a subordinate role within the superstructure of the new Irish state.

The reductions in defence budgets, an abortive army ‘mutiny’ and a general parsimonious towards public funding from the Department of Finance all led to an increasingly dysfunctional defence establishment that reached a nadir of approximately 6,000 men in strength during the 1930s.

Kinsella rightly points out that despite being called the Defence ‘Forces’, the military remained largely centred around a land army. The initial development of a naval arm was quickly defunded post-civil war and the Army Air Service, later Air Corps remained under the threat of disbandment throughout the 1920s.

The subordinate role envisioned for the military was a bipartisan affair and Kinsella’s analysis of the continuity between Cumann na nGaedheal and Fianna Fáil ministers of defence such as Desmond Fitzgerald and Frank Aiken regarding military budgets shows there was little difference in how each party viewed the issue of defence.

The supremacy of the civilian side of the Department of Defence is obliquely referenced by Kinsella and is best expressed by O’Halpin’s observation that when Peadar MacMahon transitioned from Chief of Staff to Secretary/Secretary-General of the Department of Defence, it was a classic example of ‘poacher turned gamekeeper’ and MacMahon’s extended tenure of thirty-one years from 1927-58 only exacerbated this trend towards an all-powerful civilian Department of Defence second-guessing and meddling with professional military advice.[1]

The fourth chapter focuses on the Second World War, which was known colloquially as the ‘Emergency’ in Ireland. Although this period is rightly noted by Kinsella as the largest expansion of the Defence Forces during the twentieth century, this iteration of the military never reached the power and influence of the early 1920s.

The expansion was to prove temporary and many of the new concepts and ideas that were gestated during the war, such as the highly ambitious but ill-funded Construction Corps, were swiftly abandoned post-war. The only major addition to be retained was the Irish Naval Service which remained in situ, albeit with limited resources and viewed as an adjunct to the land army similar to the Air Corps.

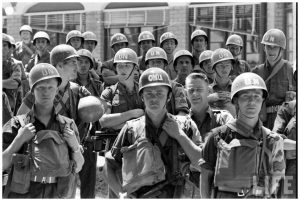

The fifth and sixth chapters chart the development of the Defence Forces post-World War II and the new roles that emerged for the Irish Defence Forces; overseas service as part of United Nations peacekeeping initiatives from 1958, and internal security along the Border from 1969 in response to the ‘Troubles’.

The return to the status quo ante of limited budgets, reductions in available personnel and inability to perform large training manoeuvres in the post-war 1940s and 1950s are intricately chronicled by Kinsella, the attention to detail vis-à-vis force readiness and the internal deliberations by the General Staff are very useful additions and is a pointed reminder that the current status quo within the Defence Forces circa 2023 has been the norm for the majority of the twentieth century.

From the 1960s onwards the Defence forces acquired a new role in UN peacekeeping.

The expansion of the military during the 1960s and 1970s reflected the need for additional internal security under the principal of Aid to Civil Power in the context of renewed conflict in Northern Ireland from 1969 and the increased role of Irish Defence Forces personnel on UN-mandated peacekeeping missions, notably in Congo from 1960 to 1964.

This dual purpose led to a mini-revival of fortunes and Kinsella neatly contextualises the differing needs of the Irish state and how the Defence Forces responded. Kinsella draws upon the rich tradition of UN peacekeeping via photographs and document extracts to illustrate the breadth of missions that Ireland took part in and continues to participate in such as UNIFIL in Lebanon.

New developments such as the opening of military recruitment to include women in the 1980s is an important aspect of the Defence Forces that Kinsella highlights, particularly the struggles and discrimination faced by women within the military generally. Kinsella also notes some of the attempts to alleviate this situation such as the creation of the Defence Forces Ombudsman, which has had mixed results.

There is also the creation of Permanent Defence Forces Other Ranks Representative Association (PDFORRA) and Representative Association of Commissioned Officers (RACO), representative bodies of the Defence Forces, which were formally authorised in 1991. These representative groups play an important role in highlighting issues of pay and conditions for serving soldiers, which often remain unaddressed, with a predictable drop in morale.

The Irish Army was expanded during the Northern Ireland conflict but military spending has been radially cut since its ending.

The seventh chapter details the most recent period of the Defence Forces history, from 2000-22. Kinsella observed that the 1990s ushered in a new era of uncertainly for the Defence Forces, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 meant that the previous external and internal roles played by the Defence Forces began to change. The end of the Cold War meant that UN peacekeeping was facing greater challenges in a multipolar world of asymmetric warfare and after the failure of the UN in Rwanda in 1994, it became clear that new procedures were required.

With the passage of the Good Friday Agreement, ending the conflict in Northern ireland and the demilitarisation of the Border, the military and police presence was reduced in border counties. This included in hindsight unusual decisions such as the sale of relatively new barracks such as Monaghan which was constructed in the 1970s.

The large reductions in the size of the Defence Forces, followed by the sale of barracks and the issuing of a White Paper on Defence all meant that the late 1990s and 2000s began to resemble the 1930s and 1950s paradigm of decreasing personnel and constrained budgets. After the crash in 2008, the Defence Forces were radically cut, facing a twenty-two percent budget reduction which has left the current military establishment with the lowest numbers since the 1960s.

The eighth and final chapter of the book which focuses upon recollections of serving and retired members of the Defence Forces in their own words is the most enjoyable and enlightening aspect of this book.

A longer and perhaps more detailed expansion of these recollections is something that is needed for future research. The ongoing Oral History project within the Military Archives is a laudable initiative and adds much needed context to an institution that can be too often caricatured through the prism of officialdom, pageantry and bureaucracy.

Overall this is a beautifully designed book, the illustrations are tasteful and often in full colour, the descriptions are helpful and the images rarely distract from the prose

As the Irish Defence Forces waxed and waned in size throughout it’s hundred-year history, the chapters on its period of largest growth, 1922-4 and 1939-45 contain the most information that would be perused by historians of both periods. However, the later chapters on the development of overseas missions and the final chapter which focuses exclusively on the voices of those serving within the military provide new and useful insights into the development of the military in more ‘lean’ years.

Overall this is a beautifully designed book, the illustrations are tasteful and often in full colour, the descriptions are helpful and the images rarely distract from the prose. An overdue update to the historiography on the Defence Forces, this book will be a key source for scholars of the Irish Defence Forces, military enthusiasts and those interested in civil-military relations in Ireland.

[1] Eunan O’Halpin, Defending Ireland: the Irish state and its enemies since 1922 (Oxford, 1999), p. 88.