Sir Charles McCarthy, from Wild Geese to West Africa

By John Dorney

On 21 January 1824, Charles McCarthy, a British officer and Governor of the Sierra Leone and Gold Coast colonies, breathed his last under a tree near the Bonsa river. He had been felled by musket balls and died, wearing his Governor’s cocked hat and red coat as the small force at his command was overrun by Asante warriors.

His path there had been far from straightforward. He was born in Ireland under the anti-Catholic Penal laws, served the French monarchy as a soldier but rejected the French revolution. He then served the British Empire as both soldier and administrator, before meeting his end as an anti-slavery governor in west Africa.

His story is an interesting insight into those Irish emigres to Catholic Europe known as the ‘Wild Geese’ and how they coped with the turmoil of revolution, war and social change in Europe and further afield at the end of the eighteen and beginning of the nineteenth centuries.

The Wild Geese and the French revolution

At the end of the Jacobite-Williamite War, after the surrender of Limerick by Patrick Sarsfield to Williamite forces in 1691, the Irish Jacobite army sailed off into exile in France, to become known, famously, as ‘the Wild Geese’.

They were continuing a tradition that went back to the late sixteenth century, of Irish Catholic military service among the Catholic powers of continental Europe of Spain, France and Austria. The 1690s marked a decisive shift into primarily French service and long after Sarsfield’s death, the French monarchy maintained an Irish Brigade. It is estimated that well over 50,000 Irishmen served in this unit over the following century. Though the rank and file of the Brigade grew progressively less Irish towards the end of the eighteenth century, the officer cadre continued to be composed of Irishmen or those Irish descent.

Most of the officer class came from Catholic gentry and landowning families who had been dispossessed in Ireland but who could rise into prominent positions in French society through military service and subsequently through business. A notable example being Richard Hennessy, who founded the famous Cognac brandy dynasty after being discharged from the military.

However, the Irish Brigade was disbanded two years after the onset of the French revolution, in 1791. Foreign regiments such as the Swiss Guard who had protected the King, were deemed politically unreliable to the new Republic, founded in 1792 after the execution of the King Louis XVI. The Irish Brigade was indeed steeped in aristocratic, Catholic and Royalist sentiment, all of which were hostile to ‘atheistic republicanism’ of the revolution. They had, after all taken an oath to the kings of France, not to the French nation which the Republic claimed to embody.

A wholly different formation, the Irish Legion, was founded by Napoleon in 1803, composed in part of refugee United Irish rebels from the rebellion of 1798, and served the French Empire until 1815.

What became of the coterie of Royalist Irish-French officers after the revolution? Some certainly served in the armies of the French Republic and subsequently those of Napoleon Bonaparte and the French Empire. Etienne MacDonald, who was of Scottish Jacobite origin but who had served in the Irish Brigade, ended up a one of Bonaparte’s most senior Field Marshals.

Most did not, however, serve the post-revolutionary regimes, where they were often suspected of anti-revolutionary politics. Those who did often came to bad ends. General James O’Moran, for instance, originally from County Roscommon, was executed by guillotine in 1794 on suspicion of conspiracy with the British during his command of French forces in Flanders. Another officer of the Brigade, Arthur Dillon, also died under the guillotine in that year for his royalist sympathies and another, Theobald Dillon, was lynched by his own troops for suspected ‘treachery’ in 1792.

Finding their dislike of the revolution to be greater than antipathy to their hereditary enemy, the British, some Irish-French officers enlisted in a short lived ‘Irish Catholic Brigade’ in British service from 1794 to 1798. Its commander was Count Daniel O’Connell of Kerry, previously the commander of the French Irish Brigade and the uncle of the better-known Daniel O’Connell, the famed Irish Catholic politician of the nineteenth century.

Some of the Franco-Irish Royalist officers, including Count O’Connell himself, eventually returned to France after the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814-5 and resumed their service in the French military. The most famous descendant of these was Patrice McMahon, a Marshal of France, who commanded the French armies that were defeated by the Prussians in 1870 and subsequently crushed the revolutionary Paris Commune in 1871. He was elected President, ironically, given his family’s Royalist politics, of the French Third Republic in 1875.

Charles McCarthy

Perhaps the strangest career path, however of French Irish Brigade officers, is that of Sir Charles McCarthy. Born in 1764 in Cork, to an Irish mother (whose surname he kept) and a French father, in 1785 he joined the French Irish Brigade. In this he was following family tradition, his maternal uncle, Thaddeus McCarthy was also a French military officer and his great grandfather Michael had been one of the original ‘Wild Geese’ in the 1690s.

He and his uncle defected after the revolution, first to a French Royalist army in exile in Germany and then to the Dutch, where he was wounded in action against French forces and then the British, who stationed him in the West Indies. After the British Irish Catholic Brigade was disbanded in 1798, he was given a commission in the West Indies regiment.

This reflected a loophole for the advancement of Catholics in British service. Whereas the ban on Catholics serving in the British military was lifted in the 1790s, Catholics could not hold commissions as officers until after Catholic emancipation in 1829. They could, however, serve as officers in colonial units such as those of the East India Company which governed British India, or in McCarthy’s case, command of back troops in the West Indies. He served in the West Indies for a number of years and subsequently in command of a militia or ‘fencibles’ in New Brunswick in Canada.

To gain a full commission however as civil or military official, one had to pledge allegiance to the British monarch as head of the Church and to renounce ‘popery’. And this McCarthy, though a practising Catholic throughout his life, did in 1811. One summary of his life comments, ‘A Catholic and devout believer… he was no bigot and he now signed the declaration against popery and transubstantiation required by office holders under the Crown’.

In 1811 he was appointed to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in Royal African Corps, a unit of black soldiers largely recruited in the Caribbean islands but stationed in the small British outpost in west Africa. In 1812 he was made governor of former French colonies of Senegal and Goree and after they were returned to France in 1814, he was made Governor of Sierra Leone and from 1822 of the Gold Coast colony (today’s Ghana) as well. He was also knighted, becoming ‘Sir’ Charles McCarthy in 1820.

The British presence in West Africa

The British presence in Sierra Leone and the Gold Coast had a most unusual history. They had established an outpost at Sierra Leone in 1787 to re-settle black loyalists who had fled the American revolution and, after they had banned trafficking in slaves in 1807, they also used it to re-settle liberated slaves from the Americas and from intercepted slave ships.

The Gold Coast, which had been used by the British, Portuguese, Dutch and Danes for the slave trade since the sixteenth century, was gradually seized by the British and formally made a colony in 1821, when it was taken off the private enterprise, the African Company of Merchants and put under Crown control.

The British had been as enthusiastic slave traders as other powers in eighteenth century. Now though, due to a complex cultural process, in which the abolition of slavery had become first a popular crusade in Britain and then national policy (though it took until 1833 for all slavery in the British Empire to be abolished), the British were an anti-slavery power. The western African British outposts were taken out the hands of the African Company of Merchants in part because they had not been enthusiastic in applying anti-slavery laws. The new governor in west Africa, Charles McCarthy, was noted to be a ‘fervent abolitionist’.

This may seem in one way contradictory, given his rejection of the French Revolution and its theoretical promise of universal equality, but the revolution’s relationship with the abolition of slavery was, to say the least, complicated. The Republic did abolish slavery in 1794, but this was unevenly applied across France’s slave holding possessions.

The black population of St Dominique (now Haiti) had to go into bloody revolt to implement it and in 1802 slavery was re-imposed in France’s Caribbean colonies under Napoleon, who also attempted to crush the Haitian revolt. By 1812 then, for McCarthy to be an active abolitionist was not in any way contradictory for a British officer and may even have been a way of demonstrating some distance from his French heritage.

As governor in West Africa, McCarthy energetically prosecuted slave trading. This was not all idealism, in part it was to hinder French influence remerging on the coast. Nevertheless, McCarthy appears to have been a genuine abolitionist and founded villages and schools for freed slaves under the Anglican Church Missionary Society. He also ran a ‘Liberated African Department’ that helped to settle over 16,000 freed slaves in Sierra Leone. McCarthy advocated ‘raising men of colour to situations of importance’ and filled his administrative posts half by white and half by black men. During his station in west Africa, he fathered children with two different mixed-race women, one inside and two others outside, of marriage.

One the many ironies of the reversal of British values and policy towards slavery in the early nineteenth century was that it brought the British into conflict with the Asante nation (traditionally written ‘Ashanti’ in English). The Asante, an African kingdom in the interior, had hitherto raided and traded in captured slaves with the Europeans, which they exchanged for European goods, including, above all, muskets and gunpowder. The British prohibition on the slave trade thus hurt their economic well being and McCarthy found himself allying with a coast people, the Fante, upon whom the Asante often preyed and who now looked to the British for protection.

Previous British administrators of the African Company of Merchants, as well as the Dutch and Danes, had felt the need to stand aside from Asante attacks on the coastal peoples. Now however, under McCarthy and direct British government control, the British took a more robust attitude towards the Asante and their king, Osei Bonsu.

War and death

When the Asante abducted a mixed-race British sergeant after a dispute between him and an Asante trader, and later beheaded him, it meant war.

McCarthy commented that he could not allow ‘chiefs who behave like that to go unpunished’. He took the Royal African Corps units from Sierra Leone and also raised a local militia and friendly tribes for a punitive expedition towards the Asante capital, Kumasi, in the dense jungle interior. He exhorted his troops to ‘support the honour and character of their country not by bravery alone but by a strict adherence to justice and humanity’.

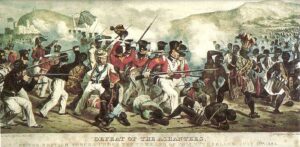

McCarthy led a force of about 2,500 men into the interior in late 1823, but disease and division of forces had reduced this force to less than 500 when, in January 1824, he was attacked by an Asante force over 10,000 strong on the banks of the Bonsa river.

At the action known as the battle of Nsamanko, his small force, composed mostly of African allies, was overwhelmed by well-armed and disciplined Asantes, predominantly armed with muskets. McCarthy himself was hit in the chest and arm by a musket ball while he was attempting to retreat over the river Bonsa. When the Asante found his body, they cut off his head and brought it as a trophy to their capital at Kumasi. The skull was afterwards paraded annually through the streets of Kumasi as part of a ritual known as the Festival of Yams. According to some accounts, Asante kings later used it as drinking cup.

An Asante attack on the coastal towns was driven back in 1826 but the war ended in a negotiated peace and it was not until the 1890s, after three more wars, that the British finally conquered the Asante nation.

In the wake of McCarthy’s death, the government of the Gold Coast was given back to the African Company of Merchants, who lacked McCarthy’s zeal in tackling slavery, sometimes replacing it by ‘apprenticeship’ of children. Crown government was not reinstated until 1843.

Charles McCarthy’s life bridged the end of the era of the ‘Wild Geese’, of loyalty to dynasties and monarchs and the beginning of the age of modern imperialism and revolution. Little known in Ireland today, his career, though highly unusual, nevertheless shows also how Irish Catholics, previously excluded from the British Empire, could begin to advance themselves within it as the nineteenth century went on.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

Sources

Stephen Manning, Britain at War with the Asante nation 1823-1900, The White Man’s Grave, p.45-55, Pen and Sword books, Yorkshire, 2021.

P. Kup, , Sir Charles McCarthy, Soldier and Administrator by The John Rylands University Library, https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/api/datastream?publicationPid=uk-ac-man-scw:1m1792&datastreamId=POST-PEER-REVIEW-PUBLISHERS-DOCUMENT.PDF

David Murphy, Sir Charles McCarthy entry, Dictionary of Irish Biography https://www.dib.ie/biography/maccarthy-sir-charles-a5122#:~:text=When%20his%20troops%20ran%20out,they%20had%20one%20son%2C%20Charles.

Joe Gannon, ‘For Faith and Fame and Honour’: The Irish Brigade in the Service of France Part 5 of 5: Semper et Ubique Fidelis

Bridget Houricane, https://www.dib.ie/biography/oconnell-count-daniel-charles-a6557

Adam Zamoyski, Napoleon the Man behind the Myth, p.328-331, Willaim Collins, London, 2018