Shunned. Ostracised. Excommunicated … Boycotted. The tribulations of Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott

By Myles Dungan

‘Mayo people do not steal, and if they shot a stranger, it would only be by mistake for a Scotch farmer or an English agent.’[1]

(Bernard Becker, Disturbed Ireland, 1881 )

Since the depredations of the Whiteboys in the 1760s, followed by their ideological successors the Rightboys and the the Rockites, parlous times were nothing new to Irish landlords and their representatives. They had grown accustomed to occasional outbursts of tenant recalcitrance, often expressed in a resort to the pistol or blunderbuss.

The Land War of the 1880s was characterized more by passive resistance and less by overt violence than previous agrarian agitation in Irleand.

But the Land League era was entirely different. While there was no shortage of weaponry in evidence, the First Land War (1879-81) was characterised by tenant strategies that were more subtle but just as unsettling as a fusillade from behind a stone wall. Passive resistance, in the form of what became known as the ‘boycott’, while it did not (until coercion legislation dictated otherwise) expose the tenant to the legal ramifications of indulging in physical violence, could be just as disconcerting as bullets for the landlord or agent.

There is a vivid term in Hiberno-English which acknowledges the ‘sneaking regard’ (usually pronounced as ‘snakin’ regard’) that certain people entertain for individuals or movements which should be, in the words of that other colourful Hiberno-English coinage ‘beyond the Pale’. In the 1880s, despite the acrimony induced by the First Land War, it applied just as unerringly to a particular class of otherwise discontented tenant who still harboured a ‘sneaking regard’ for his landlord.

This did not necessarily mean that he was prepared to man the barricades for ‘his Lordship’. He would withhold his rent like a dutiful League member. He would, more than likely, keep the knowledge to himself should he ever become aware of a plot to kill the local landowner. He would maintain the silence of the dead in the subsequent police investigation should the attempted assassination go according to plan. His sycophancy probably extended only as far as a polite refusal to pull the trigger himself, although that might just as easily have been an unerring instinct for self-protection.

This obsequiousness did not, however, generally extend as far as his lordship’s land agent.

A mythology exists of the vengeful members of secret societies lying in wait for landlords and dispatching them repeatedly to the ‘Big House’ in the sky. In reality, these enforcers were far more likely to lie in wait for fellow tenants, bailiffs, process-servers or land agents. Throughout the nineteenth century around of quarter of the tiny Irish land-owning population rarely if ever set foot in Ireland, thus benefiting from the protection of the daunting barrier of the Irish sea.

Those who did live on their own estates for some part of the year, thus theoretically sacrificing the security blanket of inaccessibility, were generally well protected by the Royal Irish Constabulary, or by the loftiness of their demesne walls. It was well-nigh impossible for even the most indomitable moonlighter to get close enough to a landlord to take a pot shot at him. Agents, however, were a different matter.

Landlords were often absentees or well protected. Land agents took the brunt of agrarian violence.

Agents were obliged to do the bidding of their masters. This, among other duties, involved frequent reports on the management of the estate which, in turn, required regular interaction with tenants. Tours of estates were generally conducted on horseback, but visits on foot to the tenantry, defaulting or in good standing, left the agent vulnerable to attack. In the early post-Famine period W.S. Trench succeeded an agent who had been murdered.

He was himself savagely beaten by the tenants on the Shirley estate in County Monaghan, recounted in his memoir Realities of Irish Life, the assassination of two other agents, Mauleverer and Bateson, and he survived two attempts on his own life.[2] There were times when it seemed as if lethal assaults on agents were a form of primitive rural self-expression, the more subtle literary variant being the writing of threatening letters, with which the most unpopular agents could have papered their walls.

That agents should have inspired such animosity is not altogether surprising. As the executors of the wishes of the landlord, and the guarantors of his or her income, they were a far more visible embodiment of landlordism than were their employers. In some instances their very wealth depended on their ability to extract payment from tenants since their own income was derived from commission on the rents raised.

Oddly, one of the less obviously abhorrent land agents of the nineteenth century has become, by some distance, the most celebrated. He should have lived his life and practised his profession in relative obscurity. Instead, he has been immortalised.

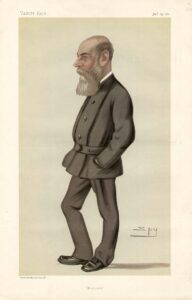

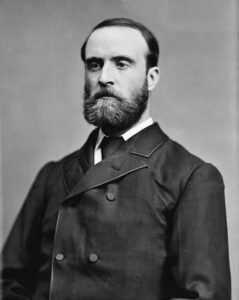

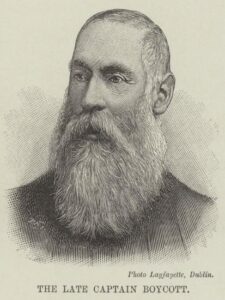

Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott was not someone whom you would have wagered a week’s wages, or part thereof, would be remembered more than a century after his death. Nor does he still adhere to the collective unconscious for any monumental achievement.

Captain Boycott

Originally from Norfolk, he was a retired military man (his army career had been unexceptional) who settled on a 2,000-acre holding on Achill Island and established a reputation there as a truculent and litigious individual.[3] After receiving a small inheritance he abandoned Achill, leased just over 600 acres of farmland on the shores of Lough Mask, near Ballinrobe in south Mayo, and took on the duties of land agent on Lord Erne’s 2,000-acre estate in The Neale, Co. Mayo in 1873.

The 3rd Earl of Erne, John Crichton, also owned another 38,000 acres outside of Mayo—when he resided in Ireland, it was in Crom Castle, Co. Fermanagh— so his holdings in the county were of relatively minor importance in his land portfolio. That was about to change.

Boycott also became a local magistrate and acquired a reputation for asperity and authoritarianism based on his appearances on the bench. The move to better land in south Mayo enabled Boycott to increase his income appreciably and indulge himself in his love of horses. His was not an especially harsh regime, although he was known for being both patronising and aloof. Neither were Boycott’s duties particularly onerous because he was required to deal with only 35 tenants.

Charles Cunningham Boycott was the agent for Lord Erne, who owned a vast estate in south Mayo.

Rents on the Erne estate, however, were inconsistent. Some were a mere 3 per cent above Griffith’s Valuation, others were closer to 50 per cent higher. One of those whose holding was in the latter category was Connaught Telegraph proprietor and Land League co-founder James Daly. Daly, in effect, was penalised for being a successful grazier while other tenants of Lord Erne—farmers of longer standing than ‘ranchers’ like Daly—were charged relatively moderate rents. Accordingly, we should never entirely mistake the campaign against Boycott for a rebellion of immiserated peasants.

One of Boycott’s cardinal errors, in addition to being in possession of a somewhat repellent personality, was to be a resident of the fons et origo of the Land War, County Mayo. His predicament flowed almost directly from Parnell’s famous Ennis, Co. Clare speech of 19 September 1880, in which the Irish party leader pointed out to his audience the ‘more Christian and charitable way’ of dealing with obnoxious individuals than that loudly suggested by some members of the crowd (‘Kill him’ ‘Shoot him’).

Instead, Parnell famously suggested:

‘You must shun him on the roadside when you meet him, you must shun him in the streets of the town, you must shun him in the shop, you must shun him on the fair green and in the market place, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of the country, as if he were the leper of old’.[4]

‘Sent to a moral Coventry’

Captain Charles Boycott was one of hundreds of victims of the practice of sending ‘obnoxious’ individuals to dwell in Parnell’s ‘moral Coventry’. But he became by far the most celebrated resident by dint of his bequeathing a new name to a very old stratagem.

In The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland Davitt traced the origins of the politics of social ostracisation back to the American revolutionary war where ‘it was remorselessly put in place by the people of Massachusetts in the early stages of the movement for American independence’.[5]

The American rebels have probably no more right to claim ownership of the practice than do the tenant farmers of Mayo.

Boycott’s problems actually predated Parnell’s enunciation in Ennis of a return to the well-tried policy of ostracisation. Boycott was one of the first authority figures to witness at first hand the decline of obsequiousness in landlord-tenant relations, for which the Land League was a catalyst.

As early as August 1879 threatening notices had been posted against Boycott, warning him not to force Lord Erne’s tenants to pay their rent without an abatement. That, however, was a mere straw in the wind since all but three of the Erne Mayo estate tenants paid up that November. In 1880, however, emboldened by the looming presence of the League, a 25 per cent reduction was demanded. Lord Erne made a counter offer of a 10 per cent cut and this was rejected.

The tenants on the Erne estate demanded a 25 per cent reduction in rents. Boycott refused.

Processes were issued against eleven tenants, but only three were successfully served. When the process-server, accompanied by seventeen RIC constables, attempted to serve a fourth notice, against a Mrs. Fitzmorris, she impolitely declined the notice and began to alert her neighbours to the presence of the server and the policemen.

Within minutes, stones, mud and manure were flying and the process-server and constabulary members were forced to retreat to Boycott’s house for their own safety. At around that time a mob also ‘chased off’ the agent’s servants and staff. Boycott was particularly vulnerable to ‘moral Coventry’ because he rented 600 acres of his own from Lord Erne. He was not unique in that respect, but many of his peers were not farming such an extensive stretch of their own land, in addition to representing the interests of their employers.

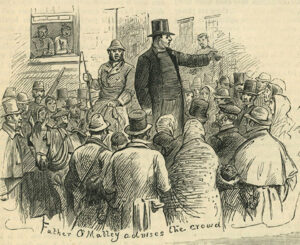

The campaign against Boycott was led by the parish priest of The Neale—a village between Ballinrobe and Cong—Father John O’Malley, president of the local Land League branch. It is to O’Malley that we can attribute the coinage of the verb and noun ‘boycott’ after one too many attempts at persuading his parishioners to adopt the word ‘ostracise’. Davitt described O’Malley as having a ‘kindly nature [and] jovial disposition’.

Boycott probably did not concur since there was bad blood between them going back to an abortive request by O’Malley for land on which to build a school.

It is to Fr. John O’Malley that we can attribute the coinage of the verb and noun ‘boycott’ after one too many attempts at persuading his parishioners to adopt the word ‘ostracise’.

With the assistance of O’Malley’s friend, the American journalist James Redpath, it took only a matter of weeks before the neologism had spread well beyond the confines of the rugged Mayo-Galway border. Davitt, in The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland describes Redpath as the ‘virtual’ and O’Malley as the ‘actual inventor of the word’. According to Davitt the epiphany came when O’Malley agreed with the American journalist that ‘ostracism wouldn’t do.’ He looked down, tapped his big forehead, and said: ‘How would it do to call it “Boycott him”?[6]

No sooner was the expression newly minted than Redpath pledged to distribute the coinage. He promised O’Malley that ‘between us we will make it as famous as the word “Lynching” in the United States’, which was a somewhat unfortunate analogy. Within a short time, the word had passed into translation, spreading at least as far east as Russia where it became ‘boikottirovat’.

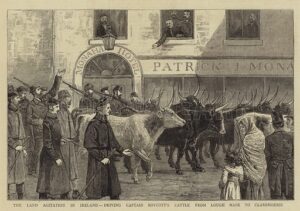

By depriving Boycott of his domestic and field staff (either by moral suasion or intimidation) and obliging or persuading local retailers to refuse to supply him with goods and services, the Land League forced the agent to carry on farm work unaided.

When, on 1 November, a few weeks after the campaign of ostracisation started, Boycott travelled to Ballinrobe to secure provisions, he recalled to the Times / Parnell Commission how ‘I was mobbed and hooted and hustled by a mob of about 500, and the police protected me’. For his own safety, he had to be confined to the local police barracks for four hours. Later in the campaign, ‘when I met people on the road they would hoot and boo at me, and spit across my feet on to the road and other annoyance of that sort’.[7]

The pro-Boycott campaign

Like most such narratives of the Land War, the travails of Captain Boycott would have been of local interest only had he not brought the world to his door by penning a letter about his plight to The Times on 14 October 1880.

In this he complained of the death threats to his herdsmen and blacksmith and the violence visited on a twelve-year old boy who was collecting his mail: ‘I can get no workmen to do anything, and my ruin is openly avowed as the object of the Land League unless I throw up everything and leave the country’.[8]

The letter evinced a considerable degree of outraged sympathy for Boycott in England, and rather less in Ireland. One of the journalists motivated to cover the story was Bernard Becker of the London Daily News. He decided to make the trip to Lough Mask to see for himself what was going on. His initial attempts to make contact with Boycott had a somewhat risible quality about them, albeit with a sinister subtext.

Boycott’s cause was taken up within Conservative circles in both Britain and Ireland as a victim of terror and intimidation.

Becker wrote largely from the perspective of the tenant and his work was an antidote to the coverage of the likes of the Times journalist Finlay Dun. Dun appears to have visited only the estates of ‘good’ landlords where all was conviviality itself, where no one was ever evicted (‘except where the tenant had become notoriously dissipated or vicious’),[9] estate land was ‘improved’ with landlord capital, compensation for ‘disturbance’ was forthcoming in the rare event of an ejectment, labourers were well paid and the tenants hadn’t a bad word to say about ‘his honour’.

While Dun’s ‘take’ on the Irish aristocracy was not an absolute misrepresentation, he was, essentially, missing the point. The First Land War was not simply about the issues he was highlighting. It was as much about the continued presence of landlords in a rapidly changing Ireland.

Becker’s coverage of the Land War was clearly at odds with that of Dun. Dun’s Land League was the ‘Irish Frankenstein’ of Punch’s John Tenniel; it was a quasi-terrorist organisation with no support other than a few limp ‘hurrahs’ raised by intimidation.

After 250 pages of his love letter to Irish property, Dun concluded that ‘Irish landlords generally secure poor and precarious returns for their land investments’ thanks largely to the ‘indolence and improvidence’ of their surly tenants.[10]

Becker, on the other hand, was more likely to go in search of the kind of landlord that Dun insisted was in short supply. He was not quite as enamoured of the Irish aristocracy as his professional colleague. Becker’s Land League was a popular organisation with secure peasant backing, though he had few illusions about the more repulsive side of its activities. Both journalistic approaches were reflective of the editorial positions of their respective newspapers. Becker’s Daily News was a liberal periodical that often found itself to the left of Liberal administrations. The Times was almost invariably supportive of the British establishment.

Alerted by Boycott’s letter to ‘a daily contemporary’ (he couldn’t bring himself to acknowledge that it was The Times) Becker wanted to find out more. However, when he enquired in Claremorris about how he might make his way to the agent’s farm, he was met with a wall of mistrustful silence:

‘nobody knew anything at all about him. He might be at the Curragh, or he might be in Dublin, and then would, one informant thought, slip over to England and get out of the trouble, if he were wise. In one of the larger stores I saw that the mention of his name drew every eye upon me, and that the bystanders were greatly exercised as to my identity and my business’.

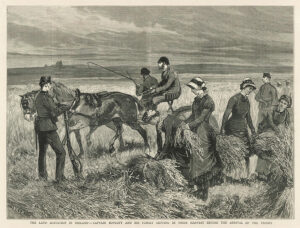

Undeterred, though fearing that he might himself be mistaken for the agent as he journeyed towards Lough Mask, Becker travelled the forty-mile journey from Claremorris in late October 1880. Arriving at Lough Mask House he was surprised to be greeted by a shepherd and shepherdess who ‘were obviously amateurs at sheep-driving’. This proved to be the case. Accompanied by a bull terrier, Boycott and his wife, accompanied by an armed RIC guard, were tending to their own flock.

Becker was sympathetic to Boycott’s predicament, describing the agent as being in a ‘state of siege’ with a permanent garrison of ten RIC constables housed on his property.

Farm labourers, workmen, herdsmen, stablemen, all went long ago, leaving the corn standing, the horses in the stable, the sheep in the field, the turnips, swedes, carrots, and potatoes in the ground, where I saw them yesterday. Last Tuesday the laundress refused to wash for the family any longer; the baker at Ballinrobe is afraid to supply them with bread, and the butcher fears to send them meat. The state of siege is perfect.

The crops still in Boycott’s fields in late October were estimated to be worth £500, except, of course, that even if they had been harvested, no one could have been found, locally at least, to purchase them. Becker described Boycott as a ‘brave and resolute man’ but doubted his ability to resist the campaign of ostracisation, ‘without his garrison and escort his life would not be worth an hour’s purchase’.[11]

When Becker asked Boycott why he did not simply leave Mayo (where he had lived for more than twenty years), the agent responded that he could not bring himself to abandon Lord Erne. Because of Becker’s obvious sympathy for Boycott’s difficulties, his account of their meeting was reprinted in unionist journals like the Belfast Newsletter and the Dublin Express. Funds began to arrive at the offices of unionist newspapers which, according to the donors, should be used the ‘raise the siege’ of Lough Mask House and harvest the crops in Boycott’s fields.

Two weeks later, when Becker returned to Lough Mask House, it was to an armed camp. Neither was he the only journalist present. The plight of Boycott had become an international cause célèbre with reporters coming from as far afield as Russia to cover his story. In the interim, the ‘Boycott Relief Fund’ of the Belfast Newsletter had raised hundreds of pounds, and supporters of the agent in Belfast proposed to send an armed force of hundreds of willing workers to harvest Boycott’s crops.[12]

The Orange Order mobilised volunteers from south Ulster to bring in Boycott’s harvest.

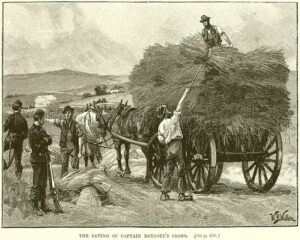

Bearing in mind that Boycott had already managed to save his own grain crops—so the work detail was coming to bring in the potatoes and turnips only— there was scepticism and alarm in Mayo as what its precise intentions were. Becker facetiously referred to the motives of the voluntary Orange labourers as ‘Ulsterior’. The chief secretary William E. Forster, intervened amid fears of a loyalist ‘invasion’ of south Mayo, and banned the incursion of an armed force of indeterminate size. Fifty unarmed volunteers would be allowed to harvest Boycott’s crops.

These came mainly from the south Ulster counties of Cavan and Monaghan and included Norris Goddard—later ‘emergencyman-in-chief’ of the Property Defence Association—engaged in the first iteration of his feud with the Land League. Boycott himself was reportedly aghast at the prospect of a detachment of fifty doughty Cavan and Monaghan Orangemen arriving on his doorstep to perform a task that, by his own reckoning, could easily have been carried out by a third of that number. He feared a sectarian bloodbath when the Mayo peasantry got to grips with the Ulstermen.

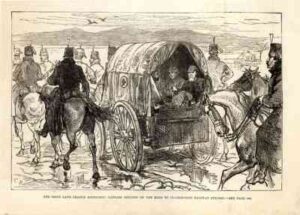

That thought also crossed the minds in Dublin Castle. The administration was now faced with the problem of guarding this highly politicised meitheal (an Irish word describing neighbours who assist each other in saving crops), which actually numbered 57 volunteer labourers, on its journey to Lough Mask, and then while it was in situ snagging turnips.

This required a force of around a thousand troops—the size of a full infantry battalion—housed under canvas in miserable Mayo November weather. The armaments on display also included 123 19th Hussar sabres and sixty additional swords of the Royal Dragoons. Had Boycott not already brought in his grain crops, the cutlasses might have usefully been pressed into service for harvesting.

The 50 Ulster ’emergency men’ were escorted to Mayo by over 1,000 troops.

With some difficulty Bernard Becker made his way back to Lough Mask House to cover the arrival of the work detail for the Daily News. He was forced to drive there himself in a private carriage, ‘hired cars being … quite unattainable. “Did your honour wish to set the country on me?” is the only reply vouchsafed by car-drivers since one of their body was cruelly beaten, presumably for the unpardonable sin of driving a policeman to the house under taboo’. Becker found Boycott to be defiant but approaching the end of his tether. ‘The combative land-agent and farmer’, he wrote, ‘himself maintains a belligerent attitude, the grey head and slight spare figure bowed, but by no means in submission.’

The progress of the Orange ‘workmen’ from Ballinrobe to Lough Mask (many of whom, as professional men—Goddard, for example was a Monaghan solicitor—would have been unaccustomed to manual labour or creature discomforts) was treated by the local population in much the same manner as its progenitor. It was, by and large, boycotted. According to Becker the large force of volunteer labourers and their armed escort (‘a huge red serpent with black head and tail’) was accompanied on the journey by ‘a dozen bare-legged girls, whose scoffs and jeers never went beyond the inquiry, “Wad ye dig auld Boycott’s pitaties, thin?”

When the procession arrived at Lough Mask House, the dispirited Orangemen exhibited an odd lack of solidarity. When it came to occupying the improvised tented accommodation provided for them, the Cavan and Monaghan men refused to be parted from their kith and kin. None of the former would agree to be housed with any of the latter. A mechanism was devised whereby ‘the edifying spectacle of Cavan and Monaghan fighting it out then and there, while Mayo looked on, was averted’.

The Orange volunteers were mocked by ‘a dozen bare-legged girls, whose scoffs and jeers never went beyond the inquiry, “Wad ye dig auld Boycott’s pitaties, thin?”

It wasn’t long before there was trouble in paradise of a different nature. No merchant within a radius of fifty miles would, or could, supply food to the force gathered in and around Lough Mask House. Neither had the military logisticians been as alert in the dispatch of provisions for the troops as their civilian commanders had been in dispatching the force in the first place. Fortunately, there was a food source available.

Unfortunately for Boycott, it was the produce of his farm. According to Becker: ‘He [Boycott] exhibits no profuse gratitude towards the officious persons who have come to help him, thinking probably that he would have been nearly as well without them …. There will be a fearful bill for somebody to pay when the whole business is over, whenever that may be’.[13]

As it transpired, the root crop rescue operation was something of an anti-climax. Apart from lining the route to Lough Mask House and offering frequent verbal demonstrations of their antipathy (‘hooting and groaning’),[14] the Mayo Land Leaguers took no further action. They may have been conscious, observing the operation from a distance, of the cost of maintaining 57 volunteer labourers and a Roman legion of support troops, and decided to accept this as a victory.

The potatoes and turnips were duly liberated from the soil at an estimated cost of £10,000, or as Bernard Becker put it, Boycott’s ‘turnips and potatoes will probably cost the country and the county at least a guinea apiece’. The entire operation, at a conservative estimate, cost in the region of thirty times the commercial value of the crop. But at least it ‘had ministered to the sense of amusement of the Irish people’.[15]

The liberation of the 17 acres of root crops also took place in often horrendous meteorological conditions—Becker’s account includes at least one near-hurricane. Davitt recounted with considerable glee that: ‘never in all the climatic records of that province did the Celtic Pluvius indulge more copiously in a pitiless downpour than during “the famous diggin’ of Boycott’s prayties” as the delighted peasantry named the costly and ridiculous procedure’.[16]

In the Connaught Telegraph, James Daly gave extensive coverage to the Boycott relief effort under the heading ‘Our Invaders’ and cheerfully echoed Davitt’s tales of wet and miserable Orange ‘tattie-hokers’. He also advised his readers against taking any precipitate action against the ‘invaders’, making it clear from his narratives that they should be left to wallow in their own misery.

Boycott’s defeat

On 27 November Boycott and his family were escorted from their farm by members of a cavalry regiment, the 19th Hussars. Because no one could be found to drive the family carriage the Boycotts were obliged to depart Lough Mask House in an army ambulance. After a hostile reception at Claremorris railway station, the family made its way to Dublin and the safety of the Hamman Hotel in Sackville Street (O’Connell Street today).

The hazards, however, continued even in Dublin. Threatening letters arrived at the Hamman and the proprietor was obliged to ask Boycott to curtail his stay. On 1 December the Boycotts took the mail boat for Wales. In March 1881 Boycott and his wife travelled to the United States under the names of Mr and Mrs Charles Cunningham. Unlike Lord Leitrim, Lord Mountmorres and dozens of agents and bailiffs, Boycott did not lose his life during the Land War, but he did, on the double, lose ownership of his name.

Boycott was forced to abandon the Erne estate, and his name became synonymous with campaigns of social ostracisation.

On 26 November 1881 United Ireland reported, erroneously (or merely malevolently), that Boycott had been relieved of his position as agent to Lord Erne and that he had been succeeded by someone with the intriguingly unpunctual name of ‘Mr. Tardy of Balla’. However, Boycott had actually returned to Ireland in September 1881 and attended a stock auction in Westport where, once again, the RIC had to step in and protect him from a hostile mob. The police, however, could not protect his facsimile and he was burned in effigy after the auction.

Boycott unsuccessfully sought compensation from a government that had clearly decided it had already invested enough in the ‘Captain’ (a title he rarely used himself). He remained as agent to Lord Erne until 1886 when he secured a more congenial appointment with Sir Hugh Adair, an English Catholic landowner based in Suffolk. However, Boycott returned to Ireland most summers and spent time on a sizeable parcel of land (Kildarra—95 acres) that he had acquired between Claremorris and Ballinlough. He bought the property in 1879 for £1,215.[17]

On 12 December 1888 Boycott appeared in public to give evidence before The Times/Parnell Special Commission. There he gave a brief outline of his travails, insisted that he had got on well with his neighbours—he didn’t specify whether he was referring to his fellow magistrates or to Lord Erne’s tenants—and read a threatening letter from ‘Rory of the Hills’ into the record which pointed out exultantly that ‘you will not have protection at hand at all times to call on’.

He then returned to the obscurity from which he had stepped unwillingly in 1880, but he was not accompanied by his name. This had long since become public property. Boycott died at the age of sixty-five in 1897, his demise inconveniently coinciding with the diamond jubilee celebrations of Queen Victoria. By the time of his death, little about him but his name was remembered by history.

However, for all his haplessness, Charles Cunningham Boycott is the only veteran/victim of the Land War, other than Parnell himself, to have been portrayed on film. He would not, however, have been greatly enamoured of his portrayal. The eponymous 1947 British-produced movie starred matinee idol Stewart Granger as the entirely fictional Hugh Davin, one of the adversaries of the unfortunate agent. Boycott himself is portrayed by the professionally pompous Cecil Parker, while Parnell is played, in a cameo appearance, by the stellar Robert Donat.

In February 1881 Monaghan Orangemen struck medals to commemorate the attempted rescue of Boycott’s turnips and potatoes. Seventy-one silvers medals in all were struck, with 57 going to the intrepid workmen who had salvaged the agent’s £350 worth of root crops.

Not all the recipients, however, were able to accept their medals in person as some had found their true calling in life. They had joined the ranks of the ‘Emergency Men’.

[Myles Dungan is the author of Land Is All That Matters: The Struggle That Shaped Irish History (Head of Zeus, London, 2024) ]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bernard Becker, Disturbed Ireland (London, 1881).

Isaac Butt, The Irish Land and the Irish People (London, 1867).

Michael Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland (London, 1904).

Dictionary of Irish Biography, (Cambridge, 2009)

Finlay Dun, Landlords and Tenants in Ireland (London, 1881).

Evidence of the Special Commission to inquire into and report upon the charges and allegations made against certain members of Parliament and other persons in the course of the proceedings in an action entitled O’Donnell versus Walter and another.

Joyce Marlow, Captain Boycott and the Irish (London, 1973).

William Steuart Trench, Realities of Irish Life (London, 1869).

References

[1] Bernard Becker, Disturbed Ireland (London, 1881), 19.

[2] William Steuart Trench, Realities of Irish Life (London, 1869), 63-64, 73-81, 185-190, 201-210.

[3] Dictionary of Irish Biography, (Cambridge, 2009) Vol.1, 702-04.

[4] Clare Independent, 25 September 1880.

[5] Michael Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland (London, 1904).278.

[6] Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland, 274.

[7]Evidence of the Special Commission to inquire into and report upon the charges and allegations made against certain members of Parliament and other persons in the course of the proceedings in an action entitled O’Donnell versus Walter and another, Book 3, 313-4.

[8] The Times, 18 October, 1880.

[9] Finlay Dun, Landlords and Tenants in Ireland (London, 1881), 15.

[10] Dun, Landlords and Tenants in Ireland, 243.

[11] Becker, Disturbed Ireland, 10, 13, 15, 16.

[12] Joyce Marlow, Captain Boycott and the Irish (London, 1973), 133-173.

[13] Becker, Disturbed Ireland, 125, 133, 136, 139.

[14]Evidence of the Special Commission, Book 3, 315.

[15] Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland, 278.

[16] Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland, 277.

[17] Dictionary of Irish Biography, (Cambridge, 2009) Vol.1, 703.