The Plantation of Ulster: A Brief Overview

By John Dorney

The Plantation of Ulster was the project by the English monarchy to colonise the northern province of Ireland with Protestant settlers from England and from Scotland.

This came in the wake of the Nine Years War (1595-1603), in which the Gaelic Irish Ulster lords resisted the expansion of the English state in Ireland. The English victory in this war paved the way for a transformation of the province.

Land in Ulster was confiscated from the native Irish lords, some of whom were compensated with land elsewhere. But some, especially those who had fled the country, were dispossessed entirely.

The Ulster Plantation was the largest and most successful of the ‘plantations’ or projects at colonisation, in early modern Ireland

It was the largest and most successful of the ‘plantations’ or projects at colonisation, in early modern Ireland. Compared to plantations in Laois and Offaly, Munster and elsewhere, the Ulster Plantation resulted in the greatest number of settlers imported, as well as the extensive construction of fortified towns to defend them. This combination meant that the settlement could not easily be destroyed even during the havoc of the Catholic rebellion of 1641.

Along with the state-sponsored plantation in the centre, west and south of Ulster, the east of the province was also ‘planted’ by private lords, mostly from Scotland, who successfully imported a large number of settlers.

The Plantation of Ulster did much to transform the social, economic, political, linguistic and religious geography of the north of Ireland. It created a solid block of Protestant settlement there that persisted into the modern era. However, the impact of the Plantation of the early 1600s can be overstated. English and Scottish Protestant migration to Ulster was not limited to the Plantation itself. Scottish Presbyterians in particular, arrived in Ulster in several subsequent waves, most notably in the 1690s.

Background – War, Flight and Rebellion

In the late 1500s, Ulster was the last province in Ireland that was mostly outside the hands of the advancing English Kingdom of Ireland. It was almost exclusively Gaelic in langauge and culture and Catholic in religion.

It was also the poorest and least developed province in Ireland, with much of the interior being covered in dense forest, mountains and bogs.

The attempt by the English to enforce their authority there led to a long and bloody conflict with the Ulster lords, led by Hugh O’Neill, who also enlisted help from restive lords all over Ireland and from Catholic Spain.

The Nine Years War, begun in 1595, ended only in 1603 with O’Neill’s final surrender to Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, at Mellifont. Much of the province of Ulster had, in the intervening years, been devasted by warfare, scorched earth tactics and famine. But the surrender of O’Neill in 1603 was not immediately followed by the plantation.

The mass confiscation of land in Ulster was made possible by the defeat of the Ulster lords in the Nine Years War, their subsequent flight to Catholic Europe and Cahir O’Doherty’s failed rebellion of 1608.

At Mellifont, O’Neill and his subordinates received very generous terms from Mountjoy, allowing them to keep their lands as long as they accepted English titles, law and English military garrisons inside their territory. There was no widespread seizure of land, punishment of former rebels or introduction of English settlers.

This conciliatory outcome infuriated many English military officers in Ireland, who felt it was a surrender to the Irish and Catholic rebels and a betrayal of thsoe who had fought them. The most prominent of this faction was Arthur Chichester, who succeeded Mountjoy as Lord Deputy (or Governor of Ireland) and the Solicitor General John Davies. Once in power they attempted to destroy O’Neill’s standing within the kingdom by legal means.

To this end they implicated O’Neill in several alleged conspiracies, supposedly aimed at restarting the war against the English presence in Ireland.

On the occasion of the last of these accusations in 1607, O’Neill was summoned to the court of King James I in London to explain himself. Fearing that he would either be arrested or assassinated, O’Neill made the hasty decision to join his fellow Ulster lords Rory O’Donnell and Hugh Maguire in their flight to continental Europe to try to secure Spanish military aid. They were never to return to Ireland. This incident – dubbed the Flight of the Earls – removed the backbone of Ulster Irish landowners. Their land was confiscated by Chichester and the Dublin Castle administration.

This still left a signficant portion of Gaelic landowners in Ulster. The remainder of the native lords there, the ‘loyal Irish’ who had sided with the English during the Nine Years War, were however, also largely removed from the scene after another rebellion in 1608 led by Cahir O’Doherty.

O’Doherty, with lands in modern counties Donegal and Derry, was provoked into rebellion by the aggressive actions of the English officer George Paulet, the Governor of Derry, who publicly punched O’Doherty during an altercation between the two men in Derry city. O’Doherty in retaliation raised his followers and in a surprise attack, burned the nascent city of Derry, killing Paulet and his garrison.

O’Doherty though, was swiftly defeated by reinforcements from England and Scotland. He was killed and other ‘loyal Irish’ lords such Niall Garbh O’Donnell and Donal O’Cahan were arrested on precaution and both died in the Tower of London. Their lands too were confiscated.

English officials Chichester and Davies had been planning a plantation or colonisation of Ulster after the flight of O’Neill and the other lords, but the circumstances of 1607-8 gave them to opportunity to implement a much more radical project than had initially been anticipated. Had it not been for the 1608 rebellion, the plantation would have been limited to the lands of those who had fled the country.

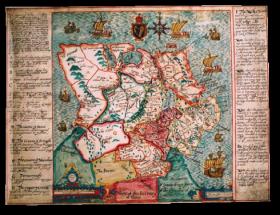

By 1610, however Chichester adn Davies were envisaging a scheme whereby all the native Irish would be removed from lands in Ulster set aside for settlers, who would all be English speaking and Protestant. To this end, they mapped and surveyed the province in 1608.

The plantation was to be both English and Scottish in character. In 1603 Queen Elizabeth I of England had died and been succeeded by James Stuart, King James VI of Scotland, who now also became King James I of England. James welcomed the plantation scheme as a joint English-Scottish venture and as a means of ‘civilising’ and pacifying Ulster, which had up to this point been the most rebellious province in Ireland. Scots would provide half of the settlers, alleviating land hunger in the lowlands and borders of Scotland.

The Plantation was also consistent with James’ previous policies in Scotland where he had tried to bring under control the independent Gaelic lordships in his kingdom and to introduce there the English langauge and Protestant religion. He had previously sponsored plantations of lowland Scots in the Gaelic-speaking Highlands and Isles of western Scotland.

Planning the plantation

The Ulster Plantation took about two years to plan and went through several drafts. Arthur Chichester, the Lord Deputy, initially favoured allocating most land to the ‘loyal Irish’, who would be resettled around military garrisons and clusters of English and Scottish settlers.

John Davies, the Solicitor General, on the other hand, favoured a more radical approach whereby the native Irish landowners would be removed entirely and replaced with three classes of English and Scottish landholders.

The first, ‘Undertakers’ would be major aristocrats from England and from Scotland who would be able to import large numbers of settlers from among their tenants and dependents. All of their tenants would have to take the Oath of Supremacy, recognising that the monarch was the head of the Church; ensuring that they would be Protestants.

The Undertakers were forbidden from taking tenants ‘of the ancient Irish race’; meaning that they were not to be either Irish or Gaelic speaking Scots. This category of Planter, about 120 men, were to import 24 families for every 1000 acres granted to them and were also obliged to built defensible towns and Protestant churches on their new estates.

The bulk of the settlers from England and Scotland were to be imported by large landowners termed Undertakers.

The second category would be ‘Servitors’; English military veterans such as Chichester himself, who would be granted lands around military garrisons. These men, numbering about 60, were permitted to take Irish tenants, presumably because they, as former soldiers, were best placed to police them.

Thirdly, there were what might be described as institutional grantees. These included the Protestant Church of Ireland and Trinity College Dublin, both of which were granted confiscated land, mostly in western Ulster.

More important, however, were the merchant companies of the City of London, whose available capital meant they were best placed to take on the expense of constructing new fortified cities at Derry (now to be known as Londonderry) and Coleraine. This turned out to be a loss-making venture, but in return they were granted monopolies on fishing and timber extraction in the region.

Finally, about twenty per cent of the land available was set aside for the remaining ‘loyal Irish’ lords. The numbers of these was culled further in 1615, when Chichester, alleging a new conspiracy, hanged several Ulster lords, including members of the O’Neill and O’Cahan families. There was to be little organised Irish resistance to the plantation, though banditry – by what the English termed ‘wood-kernes’ – remained widespread during the early years of Plantation.

The plan outlined above was broadly how the Plantation was enacted, but the number of settlers attracted proved to be considerably less than what was hoped for by the English authorities, particualrly in the west of Ulster.

In fact the largest settlement occurred in eastern Ulster, outside of the lands seized for the state-run scheme. Independent of the official Planation, in eastern Ulster, Scottish landowners, notably James Hamilton and Hugh Montgomery on their own initiative, acquired large amounts of land in Antrim and Down and settled it with Scots, largely drawn from their estates in Scotland.

The English conquest of Ireland involved creating counties as administrative units. The province of Ulster had nine counties, of which six were included in the Plantation: Armagh, Donegal, Derry, Cavan, Fermanagh, and Coleraine. County Coleraine was later abolished and divided between counties Antrim and Londonderry (or Derry). Counties Antrim and Down were not officially planted, as private settlement there was already well under way.

County Monaghan, the remaining Ulster county, was not planted either, but in its case because it had had a land settlement imposed by the English authorities before the onset of the Nine Years War, dividing it between the loyal Gaelic landholders there.

The Plantation in action

Though Ulster had been to an extent depopulated by the war and famine of the Nine Years War and although Chichester deported another 6,000 Gaelic soldiers from the province to continental Europe in 1608-9, it proved impossible to clear all the Gaelic Irish off the lands that had been set aside for the Planation. They were supposed to have been ‘cleared off’ by 1615, but in practice, most, apart from the displaced landowners, remained broadly where they were.

Though Ulster had been to an extent depopulated by the war and famine of the Nine Years War and although Chichester deported another 6,000 Gaelic soldiers from the province to continental Europe in 1608-9, it proved impossible to clear all the Gaelic Irish off the lands that had been set aside for the Planation. They were supposed to have been ‘cleared off’ by 1615, but in practice, most, apart from the displaced landowners, remained broadly where they were.

In contravention of the terms of the plantation, many became tenants of the Undertakers, or big Planters. The main reason for this was that the plantation did not attract anything close to the thousands of settlers it would have needed to totally transform the demographics of the province. In 1628, the statute banning the taking of Irish tenants was dropped.

Contrary to the hopes of the planners of the Plantation, the bulk of the native Catholic population was not removed.

Those settlers who did arrive in Ulster were typically from the border area between England and Scotland as well as the ‘marches’ or border between England and Wales. Some, upon experiencing the harsh conditions in Ulster, went home. Those who remained were typically hardy and used to armed defence of their property. Scots predominated in the east of Ulster, whereas the English presence was greatest in mid and west Ulster.

The settlers typically clustered around the best land and formed local majorities around areas such as the Bann and Laggan valleys, the walled towns of Derry and Coleraine and elsewhere. Contrary to the terms of the Plantation, a significant minority of Scottish settlers were Gaelic speaking Highlanders, some of whom were also Catholic in religion.

A survey in 1622 was disappointed with the progress of the plantation but by the 1640s it has been estimated that there were from 80 to 120,000 Protestant settlers in Ulster. This was largely the result of the initial settlers taking with them their wives and families as well as a further influx of Scottish settlement in the 1630s.

The newcomers in Ulster were as yet, however, still a minority in the province and among the Protestant presence in Ireland as whole. Nor were they the only concentration of Protestant settlement. Such areas as Dublin, Cork and elsewhere also saw extensive Protestant settlement in the first half of the seventeenth century.

However, while the Ulster plantation did not bring about such immediate and radical transformation as its planners had hoped, it had by the middle of the 1600s, indeed drastically changed the demography, language and even the physical appearance of the province of Ulster. As well as the construction of new towns throughout the province, the most visible evidence of this was the intensive felling of the forests that had once dominated central Ulster.

Further Settlement in Ulster

The Planation faced its sternest and most traumatic test in the wars of the 1640s

In the rebellion of 1641, an uprising led by Phelim O’Neill, himself a loyal Irish lord and beneficiary of the Plantation, boiled over, in Ulster, into popular assaults on the Protestant population. Between 4-12,000 of the latter were killed, but Protestant militias managed to defend their main settlements and themselves carried out numerous mass killings of Catholics in reprisal.

A Scottish army landed in Ulster to defend their countrymen and fought a Catholic army led by Eoghan Rua O’Neill, a descendant of those who had fled during the Flight of the Earls.

However, neither of these parties came out on top in the highly fragmented wars that followed; wars encompassed civil war in England and in Scotland between king and parlaiment. It was the forces of the English Parliament, ultimately led by Oliver Cromwell, who triumphed in all three kingdoms and defeated both the Irish and Scots in 1649-52. The English in western Ulster, who supported the English Parliament, were at one point besiged in Derry by a largely Scottish army which favoured the Royalists.

The Cromwellians’ victory over the Catholic Irish and their Royalist allies in 1649-52 meant that the Protestant presence in Ulster would survive, but the Cromwellians were nevertheless highly distrustful of the Scots in Ulster. At one point they planned to remove them altogether from the province and replace them with English settlers. This did not come to pass, but the Cromwellian regime did remove the last of Ulster’s Catholic landowners, whose land they confiscated as punishment for the rebellion of 1641.

During the Commonwealth and Protectorate regime of the 1650s, thousands more Scots arrived in Ulster. A high estimate of Protestant immigration into Ulster in that decade puts it at up to 80,000 people. But it was not until 1690s that Protestants and in particular Scottish Presbyterians, became an absolute majority in Ulster, particularly in its eastern parts.

Further waves of Protestant immigration to Ulster, mostly from Scotland took place in the 1650s and 1690s. By the early 18th century Ulster for the first time was majority Protestant.

There were two main reasons for this. One was a famine that hit the lowlands of Scotland in those years, meaning that many of its inhabitants fled to northern Ireland for refuge. But another was the Protestant Williamite victory over the Catholic Jacobites in the war of 1698-91.

The ‘Penal Laws’, resulting from the Catholic defeat in this war meant that Catholics could not own land over a certain amount, which freed up holdings for Protestant incomers. A Catholic Bishop estimated that up to 50,000 Scottish families had settled in Ulster between 1689 and 1715. By the 1730s, Protestants outnumbered Catholics in Ulster by about 3-2.

Presbyterians also, however, suffered from legal disabilities in the Ireland of the 1700s, due to their not recognising the established Anglican Church of Ireland, leading many ‘Ulster Scots’ to migrate again, this time to the new colonies in America.

Long term consequences

The Ulster Plantation therefore, while an extremely important turning point in Irish history, is only part of the formation of the particular character and identity of Protestant Ulster.

While it is tempting to connect the events of the seventeenth century with the twentieth century partition of Ireland, the connection is not so simple.

Counties which were planted, Cavan and Donegal, ended up outside the new state of Northern Ireland in 1920, whereas counties which were never officially planted, Antrim and Down, became its stronghold.

The connection between Plantation and Partition is not straightforward.

The Plantation certainly introduced a dynamic of sectarian and communal conflict in Ulster, which some would trace down to the present day. However, this also waxed and waned over the centuries. Presbyterians, in particular, were enthusiastic recipients of the ideas of democratic revolution and abolition of sectarian discrimination in the late 18th century. It was not until the late 19th century that Protestant unionism and Catholic Irish nationalism took on something like their moderns forms.

With all that said, the Ulster Plantation was indeed a transformative event with long-term consequences in the history of both Ulster and Ireland as a whole.

Listen to our podcast on the Ulster Plantation here:

Main Sources

Jonathan Bardon, The Plantation of Ulster, The British Colonisation of Ulster in the Seventeenth Century, Gill & MacMillan, Dublin, 2012.

Nicholas Canny, Making Ireland British, 1580-1650, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003

Padraig Lenihan, Consolidating Conquest, Ireland, 1603-1727, Pearson, Longman, London, 2009.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.