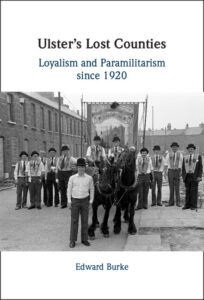

Book review: Ulster’s Lost Counties – Loyalism and Paramilitarism since 1920

By Edward Burke

By Edward Burke

Published by Cambridge University Press, 2024

Reviewer: Kieran Glennon

The late doyen of northern historians, Éamon Phoenix, often recounted the story of a Presbyterian clergyman in Donegal who had signed the Ulster Covenant in September 1912. On hearing that the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC) had given their support to the Government of Ireland Act of 1920, which separated Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan from the rest of Ulster, the minister took down his framed copy of the Covenant from above his fireplace, tore it in half and re-mounted it as a symbol of the betrayal he felt.

This book is a history of militant loyalism in the southern border counties of Cavan, Mongahn and Donegal during the conflicts in the 1920s and up to the 1970s.

In Edward Burke’s new book, Ulster’s Lost Counties – Loyalism and Paramilitarism since 1920, this anecdote is referenced to academic John Barkley. More importantly, Burke sets out to show that not all unionists in these counties adopted the same passive spirit of bitter resignation as the clergyman. Some put into violent effect the clause in the Covenant which spoke of “using all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy” – a conspiracy which, by 1920, had progressed beyond the imposition of Home Rule to one attempting to establish an independent Irish Republic.

In an important introductory chapter, Burke reviews the academic debate about the identity of his subject matter – particularly whether Ulster loyalism can be viewed as a kind of nationalism. He avoids providing a definitive judgement on the contending arguments but concludes by approvingly quoting Ian McBride: “…the Home Rule crisis saw the crystallisation of a provincial mentalité which drew upon a distinctive Protestant culture.”[1]

Burke then neatly sidesteps the entire debate, stating that for the purposes of the book, the existence and endurance of an Ulster identity is sufficient, while its status or validity as a separate nation is almost a distraction as, “…the Ulster mentalité or sense of ethnic, communal belonging, consciously structured and reinforced in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, was both persuasive and pervasive after partition in Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan.”[2]

Partition meant political unionism became redundant for these southern loyalists and – a striking observation – Ireland leaving the Commonwealth in 1949 removed the last vestiges of their British identity. However, their self-identification with what he describes as “Ulsterism” persisted.

Monaghan: resistance, reprisal and counter-reprisal

In 1911, Protestants accounted for a quarter of Monaghan’s population, being particularly concentrated in the north and west of the county. Over 83% of Protestant adults signed the Covenant and recruitment to the county’s UVF Regiment was above-average for Ulster as a whole. By the outbreak of the Great War, the county’s UVF was outnumbered by, but far better armed than, the local Irish National Volunteers.

IRA attacks in early 1920, coupled with the withdrawal of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) from small outposts into larger, easier-defended barracks, left much of Monaghan with no police presence by the summer of 1920. The IRA then set about trying to resolve its weapons deficit by raiding the homes of loyalists, with up to 100 homes targeted in a single night on 31 August 1920.

Loyalists in north Monaghan engaged in a contest in reprisals with the IRA in 1920-21.

However, in many cases, the loyalists resisted fiercely, with four IRA Volunteers being killed and 27 wounded. The quantity of arms secured was modest, but more importantly, Monaghan loyalists immediately realised the value of mutual defence, with a Protestant Defence Association being established and locals later joining the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC, or “Specials”). Here, Burke provides a timely reminder that the Specials initially operated in all nine counties of Ulster, not just the six that went on to constitute Northern Ireland. By November, they had imposed an unofficial curfew in north Monaghan, constraining IRA activities.

IRA unit boundaries overlapped county boundaries; on 21 February 1921, its Monaghan Brigade attempted to kill a B Special in the Fermanagh village of Roslea/Rosslea.[3] This sparked a watershed sequence of events.

That night, a combined force of A and B Specials, Monaghan and Fermanagh loyalists descended on the village: ten houses, a sawmill and a drapery store were burned and Catholic residents fled to the nearby hills.

Eoin O’Duffy, O/C of the Monaghan Brigade, was determined to respond in kind: “When you hit them hard they will not strike again.”[4] A month later, he ordered the shooting of four Specials and the burning of 15 loyalists’ homes on either side of the Monaghan/Fermanagh border. Three loyalists were killed, although some fought off the raiders; three more loyalists were killed in Monaghan in the following days.

However, O’Duffy’s counter-reprisal backfired: additional British troops and RIC were sent to the county and with local loyalists eager to feed them intelligence, many in the IRA were either captured or forced to go on the run. Nevertheless, O’Duffy, with typical bombast, insisted to the Dáil in August 1921 that he had cowed Monaghan loyalists: “these people were now silent.”[5]

The reality was more prosaic: clergymen from both sides in Clones had agreed a truce in April to which republicans and loyalists largely adhered, having reached an equilibrium of mutual deterrence.

In Monaghan, neither side won the local War of Independence – more importantly, neither side lost to the other. After the Treaty, membership of the B and C Specials was limited to residents of Northern Ireland, although Monaghan residents continued to serve in the A Specials. They also maintained political links, with Monaghan unionists continuing to act as delegates to the UUC into the 1920s. In return, the Orange Order quietly provided financial assistance to prevent Protestant-owned farms in the county falling into the “wrong” hands if put up for sale.

Burke’s chapter on Monaghan is deeply layered. He goes beyond the usual RIC County Inspector’s reports and references drawn from collections in Monaghan County Museum and the Military Archives by adding extracts from interviews he conducted with descendants of loyalist participants in these events. In the same vein, he also quotes from songs in the Dúchas National Folklore Collection. Bringing these extra elements of oral history and folk tradition into play make for a richer read.

Donegal: questions

However, his chapter on Donegal suffers by way of comparison, with some questions left unresolved.

Protestants were just over a fifth of Donegal’s population in 1911, with half of them concentrated in the Laggan area in the east of the county, centred around Raphoe. Burke presents a number of reasons why Donegal loyalists remained relatively quiet during the War of Independence.

Firstly, there was not much IRA activity for them to resist. This was partly due to the enduring strength of the Ancient Order of Hibernians in the county; in 1913, its Donegal membership had been over twice that of Joe Devlin’s Belfast stronghold and in 1918, East Donegal returned one of only six Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) MPs in the General Election.[6]

While IRA raids for arms held by loyalists did occur, they appear to have been quite sporadic and episodic: some were successful, some were successfully resisted and in some places, the IRA found they had been beaten to the punch by the RIC, who had rounded up many old UVF weapons. The IRA generally gave the Laggan a cautious, wide berth.

In Donegal, Protestants formed local majorities in several areas but did not engaged in much organised activity in War of Independence or Civil War period.

Burke’s second reason is the loss of UVF junior and non-commissioned officers during the Great War, although he does not quantify these losses. Those men were the pre-War subordinates of, among others, the hilariously inappropriately-named Major John Pine-Coffin. Burke says that many survived the war but “simply chose not to return to their native county.”[7] Had they done so, they would likely have played a similar leadership role to their counterparts in Monaghan.

Another reason he gives is that Donegal loyalists prioritised assisting their brethren in Derry, particularly during the sectarian violence which saw 20 people killed in the city during June 1920. This aid took the form of weapons and food, although it is unclear whether Donegal UVF members also took part in the fighting. While Derry loyalists later acknowledged in general terms the help they had received, the evidence for the arms transfers in particular seems uncomfortably scant, resting solely on an assertion by Neil Blaney, an IRA battalion commander, miffed at a UVF weapons cache he had targeted for capture no longer being there.[8]

It was not until the late spring of 1922 that Donegal saw a serious escalation of violence.

A contingent of anti-Treaty Munster IRA arrived in the county to take part in the May “northern offensive” against the Northern Ireland government. Of all places, they initially based themselves in Orange halls in the Laggan, but this was not contested by local loyalists, begging the question: had all their arms been sent to Derry as well?

At any rate, loyalists both here and further north in Inishowen soon fell prey to IRA attacks on homes and businesses.

In addition, IRA members from Derry and Tyrone, fleeing Specials’ aggression and the introduction of internment, fled to Pettigo, which straddled the border and was home to a sizeable Protestant community.

On 27 May, Fermanagh Specials attempted to retake the western side of Lough Erne but were resisted by the IRA; in the village of Belleek, a Special was killed and a Lancia armoured car was captured. The following day, a joint patrol of British military and Specials attempted to move into Pettigo but were initially repulsed.

Burke provides a superb description of what ensued and became known as the Battle of Pettigo-Belleek, based on sources not used in previous accounts – most notably, British Army records from both the War Office and regimental museums. As he notes, “Operation Basil [the re-taking of Pettigo] was an entirely military affair, aside from some borrowed USC lorries and drivers.”[9]

Therein lies a quibble. Given that Specials from either Donegal or Fermanagh were largely uninvolved, and Belleek/Pettigo loyalists were completely uninvolved other than as enthusiastic cheerleaders, this section seems to take up an inordinate amount of a chapter that is meant to discuss Donegal loyalist paramilitarism. It is a brilliant account, but also slightly off-topic.

Cavan loyalists: quiet at home, deadly elsewhere

When it comes to the third of the three counties, Burke is explicit: “Cavan loyalists failed to mount a sustained challenge to the IRA of the intensity seen in Monaghan.”[10] Indeed, he titles this chapter, “A Toothless Hound of Ulster?”

Apart from an even lower level of IRA activity than in Donegal, Burke attributes this to a dereliction of duty by the patrician leaders of Cavan loyalism: “Most of the erstwhile UVF leaders were absent, incapable or unwilling to lead loyalist resistance.”[11] Although he tries dutifully to describe what little happened, the activities of both the Cavan IRA and the Cavan UVF provide him with very slim pickings.

However, one loyalist born in Cavan did make a particularly notable contribution to this period. District Inspector John Nixon was posted to Belfast at the end of 1920; he was soon identified as the leader of what the city’s nationalists termed the “murder gang,” a group of RIC officers who perpetrated reprisal attacks on Catholics after the killings of policemen.

Cavan-born RIC Inspector John Nixon is thought to have been the head of a police ‘murder gang’ in Belfast.

Burke’s treatment of Nixon is far more restrained than it could have been, given that he states in his introduction that Nixon “embarked on a campaign of terroristic violence.”[12] After – correctly – noting that no definitive proof placed Nixon at the scene of the infamous McMahon family killings, he goes on to say that “Nixon was certainly culpable of much,” but without providing details of what this entailed; this lack of detail stands in curious contrast to the rest of the book.[13]

The British government certainly had their suspicions, although Burke merely points to their existence rather than sharing their substance. The Irish government was also suspicious – here, Burke might usefully have referenced the Ernest Blythe Papers in UCD Archive, in which Nixon’s involvement in particular incidents is explicitly traced: for example, the morning after Alexander McBride was abducted and killed in June 1921, “Nixon called on Mrs McBride to express his sorrow at the death of her husband and she recognised him as the person in charge of the party who had taken him away the previous night.”[14]

Nixon forms the centrepiece of a chapter titled “The Last Ditch – Three-County Loyalist Militancy in Northern Ireland.” Here, in a startling revelation that provides stark symmetry with the book’s wider theme, Burke notes that two other members of the “murder gang,” Constables Henry Gordon and Alex Sterritt, came from Cavan and Donegal respectively.

In addition, Nixon’s father was a close friend of William Coote, who moved from Cavan to Tyrone, where he became a Unionist MP in both the British and Northern Ireland Parliaments. Coote became closely identified with the Ulster Imperial Guards, a loyalist paramilitary organisation active in Belfast from late 1921.

Burke tracks Nixon’s later political career, which lasted into the 1940s, thus creating a bridge to an analysis of more recent decades. At this point, the startling revelations begin coming thick and fast.

The Troubles

Burke provides a wealth of information on militant loyalists with ties to the border counties and links to paramilitarism in the north – four examples stand out.

James Kilfedder, whose mother was from Donegal, was a Unionist MP from 1964 onwards. His “alleged involvement in the foundation of the modern UVF has never been proven, but … he was perceived as a close ally of those that created what became Northern Ireland’s most feared loyalist terrorist group.”[15]

Ernest Baird was born in Donegal. Having moved to Belfast, in the early 1970s he became deputy leader of the hard-line Vanguard Party, whose leader, William Craig, was fond of fascist trappings for rallies which he staged. “Baird was also convinced of the need for an armed movement under firm political leadership and championed the establishment of the Vanguard Service Crops in 1972.”[16] He was instrumental in the 1974 Ulster Workers Council strike which brought down the power-sharing Sunningdale Executive.

Burke details some engagement by border Protestants with militant loyalism in the post 1969 northern Ireland conflict.

Andy Robinson was also born in Donegal but having served in the British Army, settled in the north, becoming a member of the Specials and later a founder of the Londonderry UDA. “Robinson was suspected of being behind a number of murders in Derry and West Tyrone during the mid-1970s;” the Londonderry UDA also stabbed and shot dead a young couple near Burt in Donegal in 1973.[17]

Thomas Carson came from Monaghan but moved to Armagh, where he too became a Vanguard member; his nomination papers for the 1973 Assembly elections were signed by James Mitchell, whose farm was the key base for the notorious “Glenanne Gang,” composed of UDR soldiers, RUC policemen and UVF paramilitaries, who were responsible for a vast number of killings and bombings.[18] Among the gang members was John Weir, who was also born in Monaghan and was a serving RUC officer.

The activities of loyalist paramilitaries during the Troubles were not confined to the north. Initially, their operations south of the border were aimed at provoking a security response from the Irish authorities which would limit the ability of the IRA to mount attacks in the north from southern bases. As a result, five people were killed in loyalist bombings in the south in December 1972 and January 1973, including two children blown up in Belturbet in Cavan.

As Burke acidly notes, “Crucial British intelligence on the likely suspects was not passed onto Irish investigators at the time or since.”[19] This observation could equally apply to many other similar incidents, most notably the Dublin-Monaghan bombings of May 1974.

A febrile atmosphere

Although the Protestant Association supported successful candidates for local authority elections and a Protestant, Billy Fox, was elected as a TD for Monaghan (becoming a Senator after losing his seat), the continued existence of Orange lodges in the three counties and the participation by southern members in loyal order parades in the north fanned doubts whether border Protestants’ allegiances lay with the state in which they lived.

A long tradition of joining the RUC compounded this distrust: “…at one point during the Troubles in the Donegal Laggan village of Drumkeen and the surrounding parish, twelve local men were serving RUC constables.”[20] As the Troubles escalated, republican resentment towards southern Protestants grew and there were incidents of intimidation of individuals and petrol-bomb attacks on Orange halls.

The IRA was using the border counties, Monaghan in particular, as springboards from which to launch bomb and shooting attacks in the north. When northern loyalists retaliated with a failed attempt to kill an IRA member at his home near Clones, the finger of suspicion pointed at local Protestants, the assumption being that they were acting as a “fifth column,” supplying intelligence and even storing weapons.

One family in particular, the Coulsons, were singled out as prime suspects, seemingly for no other reason than that their grandfather had been prominent in the Monaghan UVF in the 1920s and a relative of his had been a B Special in Roslea/Rosslea. A mixed group of local and northern IRA men raided the family farm, looking for arms. Finding none, they put the family out on the road and set fire to the buildings. At that point, Marjorie Coulson’s boyfriend, Senator Billy Fox, happened to drive up – jumping from his car, he tried to flee across the fields but was chased and shot dead.

Referencing his earlier chapter, Burke notes that, “The spectre of a burning farmhouse reawakened old fears within the Protestant community of North Monaghan.”[21]

He paints a vivid picture of the febrile atmosphere in Monaghan during the 1970s, with both republican and loyalist paramilitaries active on either side of the border, each paranoid about retaliatory attacks by the other side and, amid festering mistrust, each convinced that information was being supplied about them by previously-harmless neighbours or worse, by informers within their own ranks.

Although at times the detail can get slightly overwhelming, it is clear that this intimate local knowledge about individuals, their daily activities and grandfathers’ histories was a critical aspect of the Troubles in rural areas.

Summary

Considering how often I have argued that it is appropriate to use the word “pogrom” in relation to the violence in Belfast between 1920-22, it is perhaps profoundly ironic that I find the book’s title irritating. “Lost” implies an element of accident whereas the separation of the three counties in question from Northern Ireland was very much by design. “Rejection”, “jettisoning” and “betrayal” are all words used in the book and any of them would have formed the basis for a more suitable adjective.

The book is outrageously priced at £100/€120 – it is an academic publication and so is priced bearing in mind those operating with an institutional rather than a household book-buying budget. In the interests of transparency, I should state that I was sent a free copy by the author as we share some research interests; I subsequently volunteered this review to The Irish Story. But the price tag will inevitably deprive the book of a wider audience.

This is unfortunate because the most important question for any work of history is “Did you learn something new?” and in this case, the answer is a resounding “Yes.” Burke has uncovered a hitherto neglected aspect of the three counties’ history in the twentieth century and drawn clear connections between events a hundred years ago and those in fresher memory.

He writes with obvious sympathy towards some – but by no means all – of the individuals featured. However, he does not champion their political outlook: this is descriptive, not partisan history.

Burke has crafted a compelling addition to the histories of both the Irish revolution and the Troubles, which is at once enlightening, surprising and disturbing.

It is also very good history. A blizzard of footnotes, totalling over 1300 in 300 pages of text, indicates diligent research; these are drawn from a vast array of sources, ranging from the records of the UVF in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, to those of the IRA in the Military Archives (including the often-overlooked Intelligence and Brigade Activity Reports) and those of the British Army relating to the War of Independence and Civil War period as well as intelligence summaries from the early years of the Troubles. As mentioned earlier, the archival references are supplemented by oral and folk history to build a densely-supported, but persuasive argument.

Unionists in Monaghan, Donegal and Cavan had a deep sense of “Ulsterism” which they shared with their counterparts in the six other Ulster counties. They therefore shared a deep opposition to Home Rule and so also signed the Covenant and joined the UVF in large numbers.

The prospect of partition did not weaken the resolve of all those in the three counties –some violently opposed the IRA. Here, however, it should be pointed out that with a chapter devoted to each county, the structure of the book might convey a misapprehension that this opposition was uniform – in reality, it was uneven; Burke himself is clear that the intensity of resistance varied widely between them, with Monaghan very much to the fore.

Nor was loyalists’ resistance carried out only in their native counties. District Inspector Nixon is a prime example of one who waged war inside the new Northern Ireland, against not only the IRA but also the wider nationalist population. As Burke says, “Political militancy bred violence. And loyalist terrorism succeeded in its aims, up to a point.”[22]

The book reminds readers of some conveniently-ignored truths. Firstly, Sinn Féin only achieved absolute hegemony in the First Dáil because 32 of the 105 seats remained unclaimed – those won by Unionists and the IPP. Secondly, the republican War of Independence was not a resounding triumph, opposed ineffectively by the RIC and British Army – Ulster unionism also mounted a counter-revolution, pursued most viciously in Belfast but less successfully in Monaghan, Donegal and Cavan.

While a partitionist view sees these as the three northernmost counties of what became the Free State, Burke flips that perspective on its head by pointing out that they also represented the southern and western fringes of the militant Ulster mentalité.

Although independence from Britain diminished the self-identification of these counties’ unionists with “Ulsterism,” it did not entirely destroy it. Some assimilated gradually into the new state, albeit uncomfortably and at a slight distance, while many others chose to move or retreat behind the border of Northern Ireland. In both cases, memories of the violence of the 1920s were passed down through generations.

While it would be wrong to say that DI Nixon established a template, he was not the last loyalist to make the same journey from the border counties – others did so up to and during the Troubles. Some who followed him became policemen, some became paramilitaries and some became both. Others became politicians, content to flirt with violence at an expedient remove. Some are still prominent: the parents of Jim Allister, Traditional Unionist Voice leader, stubborn opponent of both the Good Friday Agreement and the Brexit Northern Ireland Protocol, came from Monaghan.

Burke has crafted a compelling addition to the histories of both the Irish revolution and the Troubles, which is at once enlightening, surprising and disturbing. It is also a reminder that the forces which underpinned Ulster loyalism remain active, as do the paramilitaries they produced.

References

[1] Edward Burke, Ulster’s Lost Counties – Loyalism and Paramilitarism since 1920 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2024), p16.

[2] Ibid, p16-17.

[3] In one of the myriad petty sectarian idiocies to which the north is prone, the name of the village of Roslea/Rosslea is spelled differently depending on how one says the “Our Father.” Glaslough/Glasslough in Monaghan is subject to the same nonsense.

[4] Burke, Ulster’s Lost Counties, p68.

[5] Ibid, p36.

[6] Martin O’Donoghue, Faith and Fatherland? The Ancient Order of Hibernians, Northern Nationalism and the Partition of Ireland, Irish Historical Studies, Volume 46 Issue 169 (2022), p77–100.

[7] Burke, Ulster’s Lost Counties, p103.

[8] Ibid, p107.

[9] Ibid, p127-128.

[10] Ibid, p152.

[11] Ibid, p162.

[12] Ibid, p4.

[13] Ibid, p194-195.

[14] Confidential report on D.I. Nixon, University College Dublin Archives, Ernest Blythe Papers, P24/176.

[15] Burke, Ulster’s Lost Counties, p213-214.

[16] Ibid, p218.

[17] Ibid, p233.

[18] Ibid, p220.

[19] Ibid, p228.

[20] Ibid, p256.

[21] Ibid, p283.

[22] Ibid, p235.