Undermining democracy? The IRB and the 1918 election

By John O’Beirne Ranelagh. An adapted extract from his new book ‘The Irish Republican Brotherhood 1914-1924’.

By John O’Beirne Ranelagh. An adapted extract from his new book ‘The Irish Republican Brotherhood 1914-1924’.

Without the IRB, there would not have been a Rising in 1916, or an IRA, let alone a War of Independence.

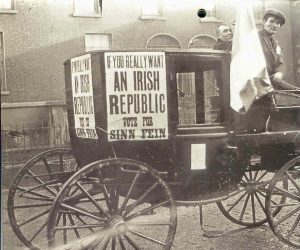

The IRB was a consciously small and elite secret society. It created the IRA. In particular, the IRB launched the 1916 Rising and its Irish Republic; it was in effect the 1916–21 Volunteers/IRA; it dominated the IRA GHQ; it successfully influenced and manipulated the Sinn Féin party, the GAA, the Gaelic League and the 1918 election – thus undermining democracy and capturing nationalist leadership.

Harry Boland, Diarmuid O’Hegarty and Collins personally selected candidates for the 1918 election, resulting in the ensuing separatist parliament – the Dáil elected in 1918 – being fundamentally unrepresentative.

On 19 December 1918, four days after the general election, the Standing Committee of Sinn Féin decided ‘to convoke Dáil Éireann’ as an Irish parliament. The IRB had managed the creation of the Dáil. Most of the ‘moderates’ in the national movement had been arrested in 1917 and were still in prison, leaving Collins and the IRB a clear field. Richard Mulcahy knew the men who had been elected (he didn’t think of including Constance Markievicz):

As far as I know, all the candidates were I.R.B. men with the possible exception of Count Plunkett and Dr White … The I.R.B. activities and interference in the selection of candidates was caused by the fear, at that time, that men would be selected who would be weak on what they considered the national issue and would submit or agree to weak compromises. They attempted to influence the selection of candidates generally and succeeded in the majority of cases.

With this background, it is hard to maintain that Irish people wanted a republic in 1918. Led by the IRB, the election was the start of an extreme nationalist takeover of erstwhile popular and moderate nationalist leadership. Eamon De Valera, like Collins, retrospectively considered that the election had been ‘fought on the principle of self-determination’ and ‘for Irish freedom and Irish independence’ and not specifically for a republic.

The results reflected anger about conscription. The arrest of the Sinn Féin leadership and suppression of the GAA and Gaelic League in the summer of 1918 added to Sinn Féin’s popularity.

Michael Hayes considered that the issue of conscription in 1917 and again in 1918 made Sinn Féin and the Volunteers/IRA the dominant forces:

‘The Rising made the Volunteers the great barrier against conscription … and that more than the IRB or anything else brought the country behind them in the 1918 election. It was conscription that convinced them, and by the way, silenced the bishops as well.’

Michael Collins, working to secure a strong Sinn Féin vote in the 1918 election, despite conscription no longer being an issue, understood that it had been Sinn Féin’s identifier and that it would be a powerful reminder that the party would fight for Irish causes. The new nationalist leadership’s determination that independence rather than Home Rule was now the objective was later stated by de Valera: ‘we took advantage of that election [1918] to make it clear that the people wanted independence’. Dan Breen reflected more extreme nationalist opinion: ‘At first the general public did not want the war. They seemed to forget that their vote at the [1918] general election led to the formal establishment of the Republic. Many of them were of the opinion that freedom could be won without any effort on their part.’

The support for the British war effort was a constant if muted challenge to Sinn Féin, the IRB, and to republican political dominance. In 1915 more Catholics than Protestants had enlisted in Belfast and in 1914–17 more Ulster Catholics enlisted in proportion to the Catholic population than Catholics from elsewhere. Some of the richest counties had the highest enlistment rates, while the poorest had the lowest, suggesting that poverty was not an incentive to enlist. A strong argument for the continuation of the IRB after 1916 was that it would stiffen the independence movement in the face of this popular support for the British war effort and a general and natural desire for peace.

Sinn Féin’s agenda was clear: withdrawal from Westminster; establishment of an Irish parliament; making Westminster/Dublin Castle rule impossible (by pacifist methods) and appealing for Irish representation at the Paris Peace Conference. All this was presented as a glamorous and ‘new’ demand for an Irish republic which otherwise differed little from the IPP’s election platform of Dominion status. And, having won the 1918 election decisively, Sinn Féin was perfectly justified to proceed on this basis.

The republican principle was welcomed unreservedly by the twenty-seven MPs present at the first meeting of the Dáil. The imprisoned leaders, however, were not so sure, feeling that a proclaimed republic had less chance of being accepted at a peace conference than would a purely nationalist appeal. IRB influence in the Dáil kept the 1916 Republic as the Dáil’s stated allegiance, but the Paris Peace Conference did not recognise it, and in any case almost certainly would not have recognised anything coming from Ireland that was not endorsed by the United Kingdom government.

A Sinn Féin convention was held in April 1919, and this time Collins and Harry Boland spared no effort to pack the Executive with their candidates. Darrell Figgis, a steady opponent of Collins, was removed. He described his experience and the IRB machinations that, he noted, were applied not just to him or Sinn Féin:

The method adopted in this case was to work through those members of the Volunteers who were sworn members of the I.R.B. and held important commands in their areas … Beyond doubt, great organisation and tireless energy were required to produce this result. It was the negation of all freedom, of course, and utterly corrupt, but it was completely successful … As I left the great hall, the Convention over, I was suddenly stopped by a strange sight. Behind one of the statues with which it is surrounded stood Michael Collins and Harry Boland. Their arms were about one another, their heads bowed on one another’s shoulders, and they were shaking with laughter. They did not see me. Their thoughts were with their triumph.

The method adopted in this case was to work through those members of the Volunteers who were sworn members of the I.R.B. and held important commands in their areas … Beyond doubt, great organisation and tireless energy were required to produce this result. It was the negation of all freedom, of course, and utterly corrupt, but it was completely successful … As I left the great hall, the Convention over, I was suddenly stopped by a strange sight. Behind one of the statues with which it is surrounded stood Michael Collins and Harry Boland. Their arms were about one another, their heads bowed on one another’s shoulders, and they were shaking with laughter. They did not see me. Their thoughts were with their triumph.

Packing Sinn Féin and the Dáil reflected deep distrust of politicians and democracy. Maintaining the IRB’s claim to the presidency of the Republic was a statement of separateness, although not a public one. The Supreme Council was resisting the thrust of the Dáil presidency becoming the Republic’s presidency – a title de Valera was to assume when in the United States from June 1919. And it was a caution that while the Sinn Féin Executive might have an IRB majority, the party was not fully controlled by the IRB and could – and did – have its own more peaceful agenda.

John O’Beirne Ranelagh is the author of The Irish Republican Brotherhood 1914–1924, published by Merrion Press 20204.