The Belfast News Letter and the Irish Civil War

By John Dorney

There were, effectively, two civil wars in Ireland in 1922-23. The first was within the new state of Northern Ireland, whose foundation was disputed by nationalists and republicans on both sides of the border. This was in large part a sectarian conflict, in which the largest category of victims came from the northern, particularly Belfast, Catholic community.

Among this community it is remembered as the ‘pogrom’, a term that Unionists vigorously disputed. The other Civil War, the conflict in the Irish Free State over whether the Anglo-Irish Treaty could be accepted, today bears the title of the ‘Irish Civil War’.

It is a commonplace to say that the Civil War in the south ended the conflict in the North by distracting republican attention from the issue of the border. And there is much truth in this. Northern Ireland Chief Secretary Wilfred Spender, for instance noted that ‘hold ups and looting [as he characterised guerrilla warfare] have nearly ceased… The conflict in Southern Ireland has drawn away many of the most active politicals from Ulster’. [1]

This article investigates how Northern Unionists perceived the southern Civil War through the editorials of the Belfast News Letter

Many hundreds of northern republicans fled south to avoid arrest, amidst a wider wave of perhaps 20,000 Catholic refugees who sought sanctuary in the Free State. Some northerners fought in the southern Civil War, predominantly on the pro-Treaty side, who offered them at least the security of paid income and political safety from arrest. Though as Kieran Glennon has shown, a significant number also ended up on the anti-Treaty side.

But what, apart from relief at its effects on the situation north of the border, was the understanding of Unionists in Northern Ireland of the war in the Free State? Both combatant sides were Irish nationalists, and both were ostensibly committed to ending the partition of Ireland.

It even seemed to northern Unionists at some points that the pro-Treaty Government might be the more dangerous enemy of the two. It possessed far greater resources than the anti-Treaty IRA and was hopeful of gaining much of the territory of Northern Ireland via the Boundary Commission instituted by the Treaty, which was due to meet in 1924.

On the other hand, however, the pro-Treaty side were committed to a settlement which would recognise the position of the Crown in Ireland and they would put down the republican ‘rebels’ as Unionists felt the British government had never done with sufficient zeal. This was, objectively, in the Northern Unionists’ interest. How then, did northern Unionists perceive the conflict over the Treaty?

To get a flavour of this, this article will look at editorials from the staunchly unionist newspaper, the Belfast News Letter, from June 1922 until May of 1923.

The Belfast News Letter

The Belfast News Letter[2] was one of the oldest newspapers in the English-speaking world, founded back in the 1730s,originally as an organ of liberal reform.

It had been taken over near the turn of the nineteenth century by a Scottish company and later by local Presbyterian industrialists, the Mackay and Henderson families. In 1922 it was owned by the brothers Trevor and Charles Henderson.[3] Its editor in 1922 was W.G. Anderson, who had had the job since 1898.[4]

The News Letter was popular among Ulster Protestants but had a lower circulation in the North than the rival (and more liberal) Belfast Telegraph. For whatever its origins in Presybterian radicalism, in 1922, the politics of the News Letter were dogmatic unionist.

The News Letter’s political orientation by the 1920s was on the right of British ‘Empire Loyalist’ politics, reprinting in full editorials from the Morning Post, which articulated the views of ‘diehards’ within the Conservative Party. Among other things, this meant taking a hard line against communism and also against the Germans, the defeated enemy of the Great War.

In an Irish context, the News Letter advocated an uncompromising Ulster Unionism, its editorials arguing that persecution of Protestants was rife across nationalist Ireland and that they could only be safe within the new enclave of Northern Ireland.

At the same time the loyal Protestants were at all times in danger of being let down by a weak-willed British government which had made far too many concessions to violent ‘rebels’ in the Treaty of 1921.

The News Letter advocated an uncompromising Ulster Unionism, its editorials arguing that persecution of Protestants was rife across nationalist Ireland

An editorial of 7 July 1922, for instance argued, ‘in all parts of southern Ireland the Protestant inhabitants are suffering from the system of terrorism organised by the rebels. Many of them have been robbed of their property; criminals who pose as “Belfast refugees” have been billeted on them at the point of a revolver and thousands have had to flee to England. There has been no such persecution in modern times of people on account of their loyalty to the King and yet it is difficult to open the eyes of the British people to what is going on almost at their doors as a result of the Irish policy of their government.’[5]

They also vehemently denied that Catholics in the North had suffered a ‘pogrom’, an allegation which they described as a false and ‘monstrous charge’. Those who had fled across the border ‘are not refugees but criminals escaping from justice… the scum of the nationalist population… Roman Catholics who live peacefully are as safe as Protestants’. [6]

‘Our government’ they wrote, had simply taken ‘suitable measures’ against republican guerrillas, in the same way as the Provisional Government was now doing south of the border. ‘Yet it [the Northern Government] was denounced by all Sinn Fein factions for “assisting an Orange pogrom to exterminate Catholics”.’ Still ,despite itself now being engaged in a counter-insurgency campaign against republicans, the News Letter agued, the same Provisional Government let lies about the alleged anti-Catholic pogrom ‘be repeated to discredit and embarrass our government’.[7]

Making sense of violence in the South

The News Letter acknowledged that the Civil War in the south had meant that violence in Northern Ireland had abated; ‘there has been a great improvement since the internecine struggle in the south took the Sinn Fein gunmen out of Belfast and the Six Counties’.[8]

There are quite a few indications, however, that the News Letter had a hard time making sense of the southern Civil War.

At times it tried to fit the fighting into the narrative of sectarian persecution of southern Protestants.

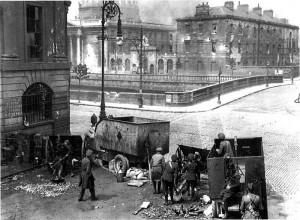

They cited incidents such as the damage to the Protestant St Kevin’s Church on Dublin’s South Circular Road, during a firefight between pro and anti-Treaty forces in July 1922, and reported the claims of Northern Ireland Prime Minster James Craig that in the fighting in Dublin, a Protestant church on Marlborough Street, near to where some of the heaviest fighting had occurred, had been damaged while the Catholic Cathedral on the same street, had been spared.[9]

At times the Newsletter tried to fit the fighting into the narrative of sectarian persecution of southern Protestants at others it wondered whether the Dublin government was actually serious about, or capable of, fighting its erstwhile comrades

But these were awkward attempts, at odds with the fact that, certainly after the bombardment of the Four Courts, fighting between the two nationalist (and mostly Catholic) factions was the main focus of violence in the south. [10]

The News Letter speculated that Protestant republican Erskine Childers, who was executed by the pro-Treaty government in November 1922 ‘died as a Roman Catholic’ because he had ‘Charles Burgess’ [Cathal Brugha]’s rosary and prayer beads with him before he was shot by firing squad. [11] Childers in fact died a proud member of the Church of Ireland (one of his last conversations was with the Anglican Bishop of Dublin) but such contradictions sat uneasily with the News Letter’s editorial line of nationalist violence being essentially sectarian.

Though it ultimately recognised that it was in unionists’ interests that the Provisional Government and the Irish Free State defeat the anti-Treaty republicans, on many occasions the Newsletter’s editorials wondered whether the Dublin government was actually serious about, or capable of, fighting its erstwhile comrades. This was common in the Northern unionist press, which often alleged that the Civil War in the south was ‘fake’.[12]

The Newsletter wondered too whether the arms, including field artillery and some military aeroplanes, given to the Dublin government by the British, might in the future be used against the Northern state. It criticised Winston Churchill’s ‘vague answer’ in the Westminster Parliament on whether the heavy weapons would be returned to the British government once the war was over.[13]

The News Letter derided the pro-Treaty victory in Dublin in July 1922 as ‘all part of a republican plan to lure them into guerrilla warfare’ and by the following year stated that the Dublin government ‘has failed to crush the rebellion and there is no evidence that it will be able to do so’. It scornfully argued the following month (February 1923) that ‘the truth is that virtually no progress has been made in restoring order since last August.’ The Free State Army ‘is no army… only a mob’ and its government ‘lurk behind barbed wire in Merrion Street [government buildings in Dublin] and pose as leaders of the country’.

Oddly, at times it evinced some back-handed regard for the anti-Treaty guerrillas, remarking in February 1923 that IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch was a ‘resourceful rascal’ who ‘could teach [National Army commandeer in chief Richard] Mulcahy more than he ever knew about guerrilla warfare’. [14] Mulcahy had of course been IRA Chief of Staff himself in 1919-21.

This was, though, a means of disparaging the capabilities of the Dublin government rather than evidence of any sympathy for the anti-Treaty republican cause. Apart from possible anxiety about the unsettled conditions south of the border, this showed a desire to discredit the governing capabilities of the Free State in order to undermine their claims and aspirations to claim or to administer Northern territory.

Poetic justice or justified reprisals?

The News Letter at times opined that the the Dublin government, many of them IRA veterans of 1919-21, were reaping what they had sown by their own campaign against the British prior to the Truce of 1921.

Upon the death of pro-Treaty Commander in Chief Michael Collins in August 1922, it reprinted editorials from the Morning Post and Pall Mall Gazette, which stated that Collins’ death in an exchange of fire in West Cork was ‘a fairer death than many of those his Sinn Fein organisation hunted down and murdered in a situation of absolute defencelessness’. [15]

News Letter editorials viewed the Dublin government as themselves violent rebels of the very recent past, but admired some of their harsh measures against republicans.

In September 1922 the Newsletter complained about the ‘disgusting Free Staters’ who ‘christen armoured cars in celebration of foul assassination’ with names such as ‘Ashtown’ (where the Viceroy Sir John French had nearly been killed by the IRA in 1919) or Mount Street (scene of some of the assassinations of British officers on Bloody Sunday in 1920). [16]

And on the opening the Third Dail – or as the News Letter described it, the ‘constituent assembly of Southern Ireland’ on September 7, an editorial stated that while ‘we take no pleasure’ in the southern Civil War, ‘we are almost tempted by the thought that the severity of the ordeal to which Southern Ireland has been subjected by the continuation of Sinn Fein guerrilla methods in the internecine Sinn Fein struggle was decreed to purge the country of the immoral, ruthless and debased spirit with which militant Sinn Fein has infected it’. [17]

On other occasions though, the News Letter wrote with some admiration of the methods used by the Free State government to put down ‘the rebel element’ – especially the 81 executions of captured republicans. They compared these favourably to what they considered had been the half-measures employed by Lloyd George’s government to put down rebellion in Ireland from 1919 to 1921.

Reporting for instance on the execution of four leading republicans in Mountjoy prison in Dublin December 1922, in a reprisal for the assassination of pro-Treaty TD Sean Hales, the News Letter was warmly supportive.

Its editorial wrote that those who were executed; Rory O’Connor Liam Mellows, Dick Barrett and Joe McCelvey, were ‘notorious leaders of the murder gangs and deserved their fate.’ That the executions had no legal basis – there were no charges laid against the four and no judicial process, did not disturb the News Letter; ‘we do not feel inclined to criticize [the Free State government] from a legal or constitutional point of view’ but rather ‘commend it for having the courage lacking in Lloyd George or in Hammar Greenwood [Chief Secretary for Ireland 1920-21]’ who ‘spared the leaders and punished the dupes’. They wrote that reprisals were necessary to end the ‘rebellion’ and that no responsible government should shy away from them. [18]

After the IRA ceasefire, in an editorial of May 1, 1923 the Newsletter admitted that the Free State government had won the war by ‘brute force more logically remorseless than anything Great Britain would have dared to employ’. It concluded that not only the military but political and ideological defeat of the anti-Treaty republicans was necessary to secure the peace: ‘there is no such thing as constitutional republican opposition, the oath [to the British monarch] is an insuperable barrier. Surrender not only of arms but of the republican idea is essential’.[19]

Conclusion

The News Letter was a particularly uncompromising organ of Ulster unionism. Its primary focus was on the North and its interest in the southern Civil War was chiefly from that angle.

It was relieved that hostilities in the south had helped to end violence in the North, and also used the outbreak of the Civil War in the south to justify the stance of the Northern Ireland government. How, they argued, could portions of Northern Ireland be handed over to a government which could not even keep order in its own jurisdiction?

The News Letter was chiefly interested in the southern Civil War for the implications it had for Northern unionists

It reported with great exaggeration of the persecution of Protestant in the south, which at times it compared to the expulsion of Huguenots from 17th century France by Louis XIV,[20] but downplayed violence against Catholics in the North. The latter it classified as merely security measures against ‘criminals’

While logic dictated that it support the pro-Treaty government that was putting down the anti-Treaty republican forces, it did not really view the Dublin government as an ally of any kind. It was sceptical of its ability to suppress fellow Irish republicans and fearful that the Dublin government, once well armed, would be a more formidable threat to Northern Ireland than the IRA.

These fears lessened as the Civil War went on. The Provisional (later Free State) governments, especially after the death of Michael Collins, dropped many of his anti-partition policies and demonstrated its resolve in crushing the anti-Treaty guerrillas.

Not only did this help the Northern unionists’ security situation, it also helped their narrative as articulated in the News Letter. Firstly, they could argue that whatever measures the Northern government had taken against republicans, they were no more severe than those taken by the Dublin government. Secondly, they appeared to prove that the republican insurgency during the War of Independence could have been crushed militarily if only the British government had had the stomach to do it.

For the News Letter though, the battle for the future of Northern Ireland would not end with the close of the Civil War but rather with the winding up of the Boundary Commission in 1925.

References

[1] Cited in Cormac Moore, Birth of the Border, the Impact of Partition in Ireland, Irish Academic Press, Newbridge 2019, p.100

[2] Commonly written the Belfast Newsletter, it was officially simply the News Letter.

[3] BBC Northern Ireland, History of the News Letter

[4] Belfast News Letter, Just 23 Editors since 1737, 15 March 2004

[5] News Letter July 7 1922

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] News Letter September 2 1922

[9] Newsletter July 20 1922

[10] Ibid.

[11] News Letter 2 December 1922

[12] Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, the Irish Civil War, Gill & MacMillan, Dublin 2004, p.251

[13] Newsletter July 12 1922

[14] News Letter, July 12, 1922 Jan 15, Feb 15 1923

[15] News Letter 25 August 1922

[16] News Letter September 5 1922

[17] Newsletter September 7 1922

[18] News Letter December 9, 1922

[19] News Letter July 12, 1922, Jan 15 1923, Feb 15 1923, May 1 1923

[20] News Letter July 12 1922

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.