David Tormey: IRA Volunteer, Garda, Nazi.

By Brian Hanley

During October 1946 the Fine Gael TD and former Longford IRA leader Seán MacEoin received an appeal for help. It came from one of his former comrades, 42-year old David Tormey from Moate, Co. Westmeath. Tormey had served in the IRA and then spent over a decade as a Garda.

Now residing in London’s Clapham, he wanted to come home and hoped that MacEoin, recently Fine Gael’s unsuccessful candidate for the presidency, could help get him a job. Moreover he was worried for his safety.

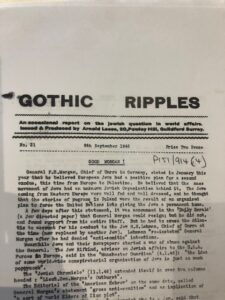

Tormey claimed that he and some colleagues were under ‘continuous supervision by touts’ and that the police had recently ‘swooped’ on them. Enclosed with his letters was violently racist material produced by the British fascist Arnold Leese and Swedish antisemite Einar Arberg. Complaining that the Irish were ‘ruled and robbed by Jewish guile’, Tormey signed off by asserting that ‘The Fuhrer still lives. Yours in National Socialism.’

David Tormey, former IRA Volunteer and Garda detective, wrote to TD Sean MAcEoin in 1946 complaining that the Irish were ‘ruled and robbed by Jewish guile’, and signed off, ‘The Fuhrer still lives. Yours in National Socialism

MacEoin responded to Tormey’s letter, but the reply is not contained in his personal papers. In a further missive, Tormey to MacEoin elaborated on his beliefs, alleging Jewish involvement in most of the disasters of Irish history, from Cromwell’s invasion onwards. He asserted that ‘Jews have been settling in Ireland for hundreds of years’ and that ‘the settlers in most cases adopted the Christian faith and usually assumed Irish names.’ Nevertheless Tormey claimed that ‘to those who have studied the Racial characteristics of the Semitic race their features are recognisable on sight.’

Hence he was in no doubt that both de Valera and Erskine Childers were Jewish and that the ‘Free State came under Jewish rule when Dev got into power and every ship that sailed in brought its load of crooks, usurers & thieves.’ Tormey’s list of ‘Jews’ included Rory O’Connor, Emmet Dalton and others. He alleged that Michael Collins ‘was a potential danger to the Jews so he was murdered.’

Moreover he was adamant that ‘there was no point in “freeing” Ireland to hand it over to the Jews … when Ireland is free Racially she will be free and only then.’ For Tormey an Irishman was only ‘an Irishman if he is Nordic. The same applies to all Europeans.’

Though Tormey lamented what he referred to as the ‘Nuremburg murders’ (the execution of Nazi war criminals during October 1946) he hoped that what he called ‘the spirit of 1921 will free Ireland from the Gall Dubh’ and that MacEoin might be prepared lead such a movement. Tormey claimed to have held these views for a decade, despite them causing him ‘much suffering including a stay in Brixton in 1941.’[1]

By any standards Tormey’s claims were delusional and his hoping that MacEoin might find him employment may seem further evidence of fantasy on his part. But we know that he did indeed return to Ireland, and in May 1948 reenlisted in the Gardai. Tormey was assigned to the Detective Branch at Dublin Castle, where he served until his retirement in 1957.[2] That was only the latest twist in a strange and at times mysterious career.

War of Independence and Civil War

David Tormey was born in 1904, the son of an agricultural labourer from Attimurtagh, near Moate. Two of Tormey’s older brothers, James and Joseph, were officers of ‘E’ Company of the 1st Battalion of the Volunteers in Athlone.[3]

David joined Na Fianna himself during 1917 and subsequently took part in arms raids and Sinn Féin election work. He graduated to the IRA in June 1920 and was involved in the wounding of a policeman in Moate that September.

Later that year he became a member of the flying column led by his brother James. James Tormey was a former Connaught Ranger, who had fought at Gallipoli while only a teenager. He worked as an attendant at Mullingar Asylum and was elected as a Labour councillor in the local elections of 1920.

Commandant by rank, his military experience made him an important IRA leader in a brigade area that spanned parts of Westmeath, Longford and Roscommon. Another brother Joseph, a railway worker, was captured and interned at Ballykinlar during November 1920.

Tormey served in the IRA in the War of Independence and the anti-Treaty side in the Civil War, but most unusually became a Garda detective almost immediately after his release in 1924

The Tormey family home was raided numerous times and their property stolen or destroyed by crown forces. In January 1921 Joseph and a fellow prisoner were shot dead by a British sentry at Ballykinlar camp. The men were ‘sheltering against a hut from a bleak wind’ but soldiers accused them of straying too close to the perimeter fence.[4] The Crown forces put on a major show of strength at his funeral, trying to intimidate mourners. Just a few weeks later James was killed in a gunbattle with Black and Tans at Cornafulla, Co. Roscommon.

After James’s funeral, the Tormey’s father, Peter, was attacked by police and suffered a broken shoulder.[5] David remained part of the flying column until captured in Ballycumber Co. Offaly in late February. He recalled how he was ‘badly beaten up by the Tans, flung into a stream and kept in a lorry from 9am to about 10pm in wet clothes.’ He believed that they would have shot him but for the intervention of a local RIC officer.[6] He was then interned and held at Rath camp in Kildare until November 1921.

After his release Tormey resumed activity, initially becoming attached to the IRA garrison in Athlone, now occupying the former British barracks. The IRA in the area largely followed Seán MacEoin’s lead in supporting the Treaty and Tormey was promoted to captain in what was becoming the National Army.

But in April 1922 as the IRA began to split nationally, Tormey was one of the minority who left Athlone barracks and joined the Anti-Treaty forces at Claxton’s Hotel in the town. While Tormey would later suggest that it would be better to ‘forget’ that the ‘ghastly’ Civil War ‘ever happened’ he was highly active during that conflict.[7]

Tormey was involved in IRA actions in Dublin, north Tipperary, South Galway and Roscommon. He held positions in local Anti-Treaty units and took part in gunbattles with Free State troops, playing a ‘leading part’ and ‘assisting in all activities.’[8] He was captured and escaped twice during 1922, first from Dublin’s Wellington Barracks during August and then Athlone Barracks in October. He was finally apprehended in Ballymahon, Co. Longford in early 1923.

After six weeks internment and following intercession by local clergy, Tormey signed an undertaking to give up armed opposition to the Free State. He explained this decision on the basis that his mother Kate was dying and that there was nobody capable of looking after her. Though many IRA prisoners signed such undertakings, doing so would have made Tormey persona non grata in republican circles.

In the aftermath of the Civil War his position seems to have been unsettled and he sought to work as a labourer. In August 1923 he wrote to the Pensions Board seeking compensation for the deaths of brothers, explaining ‘the family have lost considerably during the fight for independence and have got very little relief. There are seven children under the age of sixteen solely dependent on their parents, who are not in the best of circumstances owing to the losses sustained.’[9]

The Gardai and Spain

In June 1924 Tormey took a strange step for someone who had opposed the Treaty, by joining the Gardai. He may not have been unique in this, but it was certainly very unusual for a republican to enlist in the police at this point.

(A younger brother Peter was already a Garda). Tormey served first in Co. Kerry, in Killarney and then Beaufort.[10] The Civil War had been particularly fierce in Kerry and there was often conflict between the Guards and republicans.

Tormey was criticised by name in republican newspaper An Phoblacht for mistreatment of repubicans in Kerry in the early 1930s.

August 1931, Tormey, now a detective, came to public attention after a farmer, John M. Fleming was assaulted during a Garda raid on his home at Kilcummin, near Killarney. Fleming claimed that Tormey, armed with a rifle, had struck him across the jaw while searching his house. Fleming also alleged that Tormey cocked his rifle and pushed its muzzle into his stomach. Tormey denied this, stating that while searching for arms at the Fleming household, he had been grabbed and an attempt made to take his gun from him.

But Fleming was awarded damages in court and the incidents received front page coverage in the IRA’s An Phoblacht. They led to Tormey’s fitness for service being questioned by Fianna Fáil TD PJ Little in Leinster House.[11]

He served with Eoin O’Duffy’s pro-Franco Irish Brigade in the Spnaish Civil War.

But while several Gardai featured prominently in republican demonology as a result similar clashes, this was the only time Tormey came to public attention. The majority of his police work seems to have been low key. In any case the incident did not interfere with his career; he was actually promoted to Detective Sergeant in its aftermath. Tormey was subsequently based in Kilkenny, before transferring to Co. Waterford during 1934.

In November that year he reverted to the uniformed force, later claiming this was because of political differences with the Fianna Fáil government.[12] He next came to public attention in September 1936 when he resigned from the Garda altogether to join Eoin O’Duffy’s Irish Brigade for Spain.[13]

Indeed Tormey was one of the first ten volunteers in the advance party that left Dublin that November on the Lady Leinster for Liverpool.

He was the subject of profiles in the strongly pro-Franco Irish Independent, which neglected to mention his Anti-Treaty stance and in his local paper, the Westmeath Independent, which did.[14]

Tormey was initially ranked First Lieutenant before being promoted to Captain and Officer Commanding B Company of the Irish Brigade.[15] There is little known about his time in Spain, though he would later claim that while there he advised O’Duffy to think racially, claiming that ‘if O’Duffy had studied Racialism he would have succeeded.’ However he lamented that O’Duffy was ‘surrounded by spies all the time’ and hoped that ‘one day the spies will pay the price.’

Retracing Tormey’s time in Spain and his place in the various disputes that wracked the Brigade is difficult. He had begun the process of applying for a Military Service Pension during 1935. Providing a detailed account of his activities he stated that ‘as I am Member of the Garda I cannot be a member of the Old IRA Association, or, any other Organisation interested in these Matters.’[16]

Emigration and return

But this process was interrupted by his time in Spain. Having missed an interview with the assessors in January 1937, his application was stalled and he faced queries about the lack of information for his pre-Truce service. He was living in Dublin’s Donnycarney during the summer of 1937 and was out of work. Old comrades began to lobby on his behalf, with an IRA veteran from Moate, John J Daly pleading that Tormey ‘is now in very poor circumstances … in fact he is destitute and has got no home.’

Daly claimed that Tormey had given up ‘a very remunerative position in the National Army to fight against the Treaty’ and that only ‘internal disputes and jealousies’ among Athlone veterans had prevented him getting the required references for his 1917-21 service.[17] But Tormey, in common with many applicants, would face continual frustration in his attempts to access a pension.

Tormey emigrated to England after his return from Spain where he claimed to have been interend during the Second World War due to his pro-Nazi views.

He left Ireland again in the winter of 1937, firstly for Liverpool. He then settled in Birmingham for two years, finding work as a steel fixer. During the Second World War he would live in London’s Ealing during 1940, return to Birmingham during 1942, move to Suffolk in 1943, and then back to London’s Pimlico by 1945.

Throughout this period he maintained correspondence with the Pension Board. Tormey often expressed anger with constant rejections, alleging that there were those who ‘draw pensions to-day whose military exploits amounted to giving three cheers or an occasional hasty retreat from a potential mother-in-law’ while others got nothing.

He blamed the makeup of the Board itself, suggesting that ‘it is an appalling state of affairs that Peelers sons in the Civil Service and an ex BA Recruiting Sgt … should be in a position to carry out vendettas of this description.’ He was moved on one occasion to threaten revenge on those blocking his application, promising that what he called ‘guttersnipery will one day be repaid in the same manner.’ [18]

But while Tormey complained bitterly, he never betrayed any sense that there was more to the case than the familiar problem of time-servers obstructing him. There was little sense of the racist conspiracy theorist that revealed himself in the letters to MacEoin. Though he told MacEoin that he had been jailed for his beliefs in Brixton prison during 1941, this does not seem to have been noted by the Pension Board (who were usually aware of criminal charges against applicants).[19]

Possibly due to the intercession of his one-time IRA commander Sean MacEoin, Tormey was reinstated as a Garda detective in the late 1940s.

And if indeed Tormey was interned, it was evidently not for very long.[20] While the tone of his 1946 letter to MacEoin suggests immersion in fascist circles, to what extent he was involved in them is unknown.[21] But reasonably soon after his letters to MacEoin, things began to look up for Tormey.

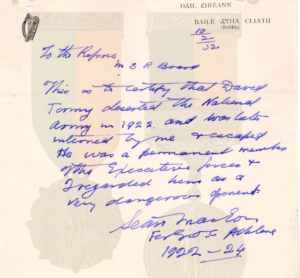

By the summer of 1948 he was a Garda detective again. By the time he reenlisted there was a new inter-party government in Dublin and its Minister for Justice was one Seán MacEoin. That Minister would provide Tormey with a positive if pithy pension reference during 1952 writing that ‘David Tormey deserted the National Army in 1922 and was later interned by me & escaped. He was a prominent member of the Executive Forces & I regarded him as a very dangerous opponent.’[22]

Tormey also received new references from several other veterans, of both pro and anti-Treaty varieties.[23] By the time he retired from the Gardai in 1957 he was in receipt of a full Military Service Pension. At some point in the next few years Tormey again emigrated to Britain, dying there, aged 62, during 1966.

Unexplained questions

The story raises several questions. Did MacEoin feel obligated to aid Tormey, despite the unhinged views expressed in the letters to him? The Tormey family, after all, had sacrificed much for the national cause.

As early as January 1923 MacEoin had lobbied for compensation for the Tormeys, noting that though ‘Davie’ was currently an anti-Treaty prisoner, the family were in ‘very poor circumstances.’[24]

Perhaps in 1946 he considered Tormey’s views just more extreme versions of commonly held prejudices. The allegation that de Valera was Jewish and that Jews were gaining positions under his government were common tropes among supporters of Fine Gael during the 1930s.

Indeed during 1934

MacEoin himself had told a Fine Gael rally in Co. Meath that ‘the Jews never got into a

country but they tried to control it’ and referenced what he alleged was increasing Jewish

ownership of Irish factories and Jewish involvement in communism. [25]

The Christian Front rallies that accompanied the pro-Franco fervour of the summer of 1936 invariably saw antisemitic rhetoric as well. Tormey obviously felt he could say what he liked to his old commander and it is perhaps a reflection on political culture at the time that antisemitism was unremarkable.

Whether Tormey expressed similar opinions to friends and colleagues back in Dublin we simply do not know.

In his pension correspondence his language was quite measured, if occasionally sarcastic. Those who backed his applications may have had little notion of his beliefs. Patrick Morrissey, for example, an Anti-Treaty veteran who generously provided Tormey with a reference, presumably did not know that he was one of those identified as being of Jewish descent in the letters to MacEoin.

Tormey’s story suggests that Irish people, including veterans of the revolution, were not immune to the lure of fascism

But Tormey also claimed to have been jailed for his politics and surely the Gardai should have had some difficulty reenlisting a man with a criminal record. Could there have been an even more murky story regarding the Civil War?

After all Tormey deserted the Free State side to join the Anti-Treatyites and then travelled widely, linking up with units across Ireland. He engaged in armed actions, was captured and escaped on two occasions. When finally interned he signed an undertaking to forego opposition to the state and within a year he was accepted into the Gardai.

While none of these things were unique on their own, together they are perhaps suspicious. But several republicans, including Seán O’Farrell and Patrick Morrissey, had no qualms with providing Tormey with references and do not seem to have doubted his bone fides.

I first read Tormey’s letters to MacEoin over 20 years ago. My impression then was that they complicated the narrative that the men who followed O’Duffy to Spain were simple country lads, inspired by Catholic anti-communism. Tormey was clearly more than that. But it was only the release of the Military Service Pensions and other sources such as the Civic Guard Register at UCD that allowed me to develop a more complete picture of his background and career.

Tormey’s story certainly confirms that Irish people, including veterans of the revolution, were not immune to the lure of fascism. It also illustrates that such opinions were not a barrier to employment, even in the police, provided, perhaps, that you knew the right people.

I am very grateful for the assistance of Kate Manning, Sam McGrath, Conor Dodd, Maurice Casey, Jack Traynor, John Sheehan and Paul Hughes in writing this article. Any further information about David Tormey, particularly his time in Britain, would be greatly appreciated.

References

[1] David Tormey to Seán MacEoin, 14 & 22 October 1946, Seán MacEoin Papers, University College Dublin (UCD) Archives P151/914. Enclosed with the first letter were copies of Leese’s Gothic Ripples, 8 September & 22 September 1946, and the Swedish-published pamphlets ‘What did Jesus say to the Jews?’ and ‘The Jews are also human beings: some people say.’

[2] Civic Guard Temporary Register UCD, 19 May 1948. Garda Review, Vol. 32, No. 3, 1957. (My thanks to Conor Dodd for this information.)

[3] For a detailed account of James and Joseph Tormey, see John Sheehan, ‘Brothers-in-arms: the Tormeys’ in J. Crowley etc (eds) The Atlas of the Irish Revolution, (Cork University Press, 2017) pp. 358-362.

[4] TF O’Higgins, 13 December 1923 in Military Service Pension (MSP) file 1D155 (Joseph Tormey).

[5] Peter Tormey, to PW Shaw TD 6 July 1927 in MSP 1D154 (James Tormey).

[6] The information on David Tormey comes from accounts in MSP 34REF16999 & 34E9621 (David Tormey) and his brother’s MSP’s (above).

[7] D. Tormey, 6 December 1952, MSP 34REF16999.

[8] Seán O’Farrell, (Leitrim Anti-Treaty IRA commander) 9 February 1952, MSP 34REF16999.

[9] D. Tormey, 2 August 1923, MSP 4380B. (My thanks to John Sheehan for this reference).

[10] Civic Guard Register, 20 June 1924.

[11] Kerry Reporter, 24 October 1931. An Phoblacht, 31 October 1931. Dáil Debates, 5 November 1931.

[12] Weekly Irish Times, 3 November 1934.

[13] Irish Independent, 14 November 1936.

[14] Westmeath Independent, 21 November 1936. In his memoir O’Duffy also elided any mention of Tormey’s membership of the Anti-Treaty IRA. Eoin O’Duffy, Crusade in Spain (Dublin, 1938) p. 90. (Thanks to Jack Traynor for this reference).

[15] Robert Stradling, The Irish and the Spanish Civil War (Manchester, 1999) p. 97.

[16] D. Tormey, 6 April 1935, MSP 34REF16999.

[17] John J. Daly, 23 July 1937, MSP 34REF16999.

[18] D. Tormey, 6 May 1946, 10 July 1946 & 2 June 1948, MSP 34E9621.

[19] The only case of a David Tormey featuring in a criminal case was when a hospital porter of that name was acquitted along with another man of the robbery in Islington in October 1941. He is reported as being aged 40 while David Tormey would have been 36. Holloway Press, 24 October 1941. (Thanks to Maurice Casey for this information).

[20] Tormey is not among those listed as British Union of Fascists internees, though members of other Nazi groups were also jailed.

[21] Arnold Leese and his circle were certainly under surveillance during 1946, the same period Tormey complained of police harassment. In 1948 Leese and several supporters would be jailed for aiding Dutch Nazis escape to South America.

[22] S. MacEoin, 19 February 1952, MSP 34REF16999.

[23] His referees were Thomas Claffey, Seán O’Farrell, Patrick Morrissey, Seán MacEoin, John J Daly, Ciaran Walsh, David Daly and William Rowe.

[24] S. MacEoin, 23 January 1923, MSP 1D155.

[25] Drogheda Independent, 9 June 1934.