‘A bad fight, a disgraceful fight’, Tom Barry in the Civil War

By John Dorney

Tom Barry was a most headstrong and abrasive young man in 1922. Aged 25, he had fought in both the Great War and the Irish War of Independence, the first in the British Army, in the second, against it, in the IRA.

He emerged from the latter conflict as a legendary guerrilla leader, convinced that he was the foremost military leader in the guerrilla army. Even those – and they were many – who personally disliked him and his bombastic manner had to concede his skills as a combat commander.

Ernie O’Malley, for instance thought that officers such a Sean O’Hegarty in Cork and Michael Kilroy in Mayo were ‘far way ahead’ of Barry, in terms of revolutionary organisation and building up guerrilla infrastructure in an area, but, ‘as far as fighting was concerned and handling a column he [Barry] was the best man I knew’. [1]

During the Civil War Tom Barry’s relationship with the leadership of the Republican Army broke down into the most bitter acrimony

In the Civil War of 1922-23, a conflict where Barry assumed, or attempted to assume, a role as a senior decision maker in the anti-Treaty IRA, his relationships with the leadership of the Republican Army broke down into the most bitter acrimony. The disputes were not so much ideological as much as a clash of personalities and egos.

Barry veered from total intransigence before the war broke out, blocking efforts to avoid a conflict between Irish nationalists, to multiple efforts at starting peace talks on his own initiative during the fighting, to advocating the surrender of Republican arms by the end. The period ended with his resignation from the IRA leadership and a long-standing chasm between him and those who went on to form political leadership of Fianna Fail, Ireland’s dominant political party for much of the twentieth century.

Before the Civil War

Barry had been a late convert to Irish republicanism, as we have seen in a previous Irish Story article. Many in the IRA distrusted him due to his service in the British Army in the Great War and his membership of veterans’ organisation once he returned home.

However, once he was admitted into the IRA in late 1920, he quickly proved his worth to the organisation, commanding numerous successful small unit actions at Kilmichael, Crossbarry and elsewhere. He also – perhaps in order to prove himself to his doubters in the IRA – displayed a notable ruthlessness, wiping out an entire patrol of Auxiliaries at Kilmichael and showing no compunction afterwards at shooting alleged civilian informers.

During the Truce with the British of 1921, Barry had been named by Michael Collins as liaison officer with the British forces in Munster, tasked with making sure the truce held.

In the lead up to the Civil War, Barry proposed toppling the pro-Treaty government and establishing a miitary dictatorship

In common with the majority in the IRA Southern Divisions, he rejected the Anglo-Irish Treaty as a compromise too far and was elected onto the anti-Treaty IRA Executive in March 1922.

But Barry showed an unusual assertiveness in the months before the outbreak of Civil War. While some, such as Liam Lynch, the anti-Treaty IRA Chief of Staff, spent months attempting to negotiate a compromise with Michael Collins and the pro-Treaty leadership, Barry was among those IRA figures who argued that a military clash was inevitable and that republicans should take the initiative.

It was perhaps, an indication that Barry always thought primarily in military rather than political terms. But it was also due, in part, to his impetuous and belligerent character.

When, in Limerick in March 1922, a stand-off occurred over forces from which side of the Treaty split would occupy the city, Barry was adamant that force must be used to uphold the anti-Treatyites’ claims.[2]

As it was, the intervention of Liam Lynch, Eamon de Valera and others helped to defuse the situation and the city’s barracks, once vacated by the British Army and Royal Irish Constabulary, were shared out between pro and anti-Treaty garrisons.

Barry viewed this as a mistake, the first in a series of missed opportunities, ‘We who were then on the Army Council, held the view that the Treaty people were only playing for time until the spilt in the anti-Treaty forces had widened and they had built up an army of Staters to attack us’. [3]

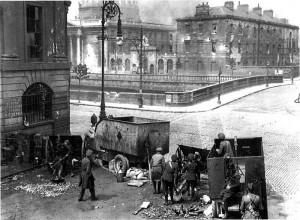

In late June 1922, the IRA Executive met in Dublin’s Four Courts, which they had occupied in the previous April. At this juncture the Irish Free State had had its first election, resulting in a pro-Treaty majority and the anti-Treatyites were scrambling to assemble a coherent policy in response.

Barry, along with Ernie O’Malley, a man he was later to fall out with bitterly, had attempted to disrupt the election, seizing the ballot papers from the National University of Ireland and raiding the armoury of the new police force, the Civic Guard in the Curragh. He also helped to smash up the press of the Freeman’s Journal, which had taken a pro-Treaty line. [4]

These actions did not, to put it mildly, dispel pro-Treaty charges that the anti-Treaty republicans constituted a danger to the nascent Irish democracy.

All attempts at derailing the acceptance of the Treaty having failed, Barry’s proposal was the overthrow by force of the Provisional Government, the establishment of a military dictatorship and a notification to restart hostilities with Britian in 72 hours. [5]

Cooler heads within the IRA prevailed and Barry’s motion was defeated. This caused a split between the Four Courts faction, with which Barry was aligned and the IRA leadership under Liam Lynch, who was viewed, at this date, by the Four Courts faction, as too moderate.

Barry again later voiced his great regret that they had not overthrown the Provisional Government when they had had the chance ‘I would have rushed 5 or 6,000 men to Dublin and made prisoners of Provisional Government’, he later told pro-Treaty troops who had arrested him[6].

Outbreak of Civil War and Escape from prison

When the Civil War broke out with the Pro-Treaty government’s bombardment of the Four Courts on June 28 1922, Barry was on the new border, scouting possible incursions into Northern Ireland, part of the initiative of the Four Courts leadership to provoke the British into re-invading the 26 counties in order to bring down the Treaty.[7]

Upon hearing that fighting had broken out in the capital, Barry hurried back to Dublin and attempted to enter the besieged Four Courts – apparently disguised as a female nurse – but was arrested by Free State troops and imprisoned in Mountjoy Gaol in Dublin.[8]

The period leading up to the Civil War therefore, saw Barry adopting the role of republican extremist, urging a military solution involving some sort of military coup. This was the opposite of the position he would take later in the Civil War. What was constant, however, was his unwillingness to take orders from the republican leadership and in particular from Liam Lynch.

Barry was imprisoned at the otubreak of the Civil War but escaped in September 1922 from Gormanston Camp.

Barry spent about two months in the Free State’s prisons, threatening hunger strike unless he and the other prisoners were granted ‘visits, freer mail and control of the kitchen’.[9] On being transferred to the internment camp at Gormanstown, however, in early September, he escaped almost immediately.

By September 9, the anti-Treaty IRA leadership, by now conducting a clandestine guerrilla war against the Free State, were discussing in excited terms the uses to which Barry, a celebrated military leader, could be put, Lynch remarking to Ernie O’Malley, then head of the IRA’s Eastern Division, that he would be ‘a most useful officer’ who ‘could pull off some big coups’.[10]

Ernie O’Malley’s orders were apparently to have him link up with Frank Aiken, who commanded a large and well armed concentration of IRA guerrillas in the north Louth area. Instead, though, Barry made his way south on foot, back to his native Cork.

At the time, O’Malley was philosophical about this, resignedly writing to Lynch that, ‘He [Barry] evidently did not receive my letter asking him to stay in Fourth Northern area or if he did, did not consider it advisable to stay there.’[11] In later years though O’Malley expressed himself more bluntly; ‘I sent him north to get arms from Aiken’. Instead of doing that he went down south and I was very annoyed. They had enough fellows down south.’ [12]

It would not be the last time that Barry would flout the orders of his superiors in the anti-Treaty IRA.

In the field

It is not entirely clear what Barry did in September and October 1922. This was a time of considerable trouble for the Provisional Government of the Free State, as its hastily raised and ill-equipped army struggled to keep control over the countryside of much of the south and west of Ireland, amid persistent guerrilla attacks from the anti-Treaty IRA.

Barry however appears not to have entered the fray until November 1922.

In October, he and Liam Deasy were involved in peace feelers with Tom Ennis, ex of the Dublin IRA and now a commandant with National Army troops in Cork. Barry told Ennis that his heart and those of his men were not in the Civil War, that he was ‘most anxious for peace’ and that ‘he had not fired a shot yet’.[13]

The anti-Treatyites, Ennis reported to the Government, proposed that the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown and the ‘British veto’ be removed from the constitution, that both armies be demobilised and that the ‘Old Volunteer Army’ be brought back together under a new executive formed by both pro- and anti-Treaty officers. They expressed a willingness to surrender their arms but asked for more time to arrange it.[14]

The Dublin government was most disapproving of Ennis’s contacts with Barry and not long afterwards he was stripped of his command in Cork and brought back to Dublin.

It was only after this point that Tom Barry entered the Civil War in earnest.

Barry pulled off several highly successful attacks on towns in November and December 1922.

Barry later claimed that he held the rank at this point of ‘GHQ Southern Division’ but it appears that he in fact occupied a much looser position of Director of Operations in the Southern Divisions. This, in reality, suited Barry’s independent streak, allowing him to devise operations with improvised units raised from local IRA columns all across the province of Munster. [15]

In terms of tactical skill at such operations, both the pro-Treaty authorities and Barry’s comrades in the IRA all acknowledged his prowess.

Barry, putting together a force of several hundred men in west Cork, successfully took the towns of Ballineen and Enniskeen on November 4, 1922. The pro-Treaty National Army wrote that there were simultaneous attacks on the two adjacent towns, garrisoned by about a dozen men each, the attack at Enniskeane being led by Barry personally. Both garrisons were forced to surrender with three killed and nine wounded on their side and two anti-Treatyites killed. [16]

According to his enemies in the National Army, Barry subsequently proposed, at an IRA meeting as Ballingeary, another assault on the small town of Inchigeela, near the Kerry border, but could not secure agreement from the local units.[17]

Ranging further afield, Barry on December 9, 1922, commanded about one hundred men drawn from three columns in the South Tipperary Brigade, with Dinny Lacy, to capture the town of Carrick on Suir.

A glimpse of Barry’s habitual boastfulness can be gleaned from his entry into the guardroom of the barracks in Carrick, where about 100 pro-Treaty prisoners were held. According to Sean Cooney, ‘Do you know who I am he asked. No reply. I am Tom Barry of Cork and I’ve captured hundreds of you fellows. He had two guns in his belt. No one said anything’. [18]

Barry left the area shortly afterwards, returning to Cork, but the Tipperary columns proceeded also to take a series of local garrisons at Callan, Thomastown and Mullinavat in County Kilkenny.[19]

In these operations, forces under Barry’s command captured perhaps up to 200 prisoners and a great deal of arms and ammunition.[20]

Liam Lynch, in correspondence with Eamon de Valera at this date acknowledged that Barry had set an example of what could be achieved by guerrilla commanders.[21] But this aura of success was not to last.

For one thing, all such successes were temporary. Towns taken in such attacks had to be abandoned when numerically superior government forces were assembled. Prisoners had to be let go. Even arms captured often had to be dumped for safe keeping between operations.

The National Army in Cork noted that the large columns temporarily assembled by Barry, up to 3-500 strong in their estimation, had broken up by late December and Barry’s men now moved in groups of only 6-12, with rifles dumped and carrying only ‘short arms’. Only in the hill country around Ballyvourney could they hold territory in any numbers. [22]

Though the Free State worried in late 1922 and early 1923 that it might collapse due to bankruptcy, on the other side amid mounting arrests and executions of their fighters, demoralisation was setting in.

The tide turning

By January 1923, Barry was already restarting attempts at peace-making, which he had flirted with since the previous autumn. Barry backed peace moves by a Fr Tom Duggan and the Neutral IRA, an organisation headed by fellow Cork man Florence O’Donoghue, which proposed the dumping of arms by both sides. Barry met Lynch in Dublin that month and according to Gerard Shannon’s biography of Liam Lynch, his proposals so infuriated the IRA Chief of Staff that Lynch told his secretary Madge Comer that he felt like having Barry killed.[23]

Lynch’s trajectory in the Civil War was the opposite of Barry’s; a moderate before the bombardment of the Four Courts, who became increasingly irreconcilable to the Free State as the Civil War dragged on.

Barry appears to have contemplated another offensive in February 1923, but at this date, something happened that would completely alter his attitude towards the Civil War. Liam Deasy, his Divisional commander, was captured and in custody, issued a statement that all men under his command should surrender and give up their arms.

From early 1923, Barry was adamant that the anti-Treaty campaign should be called off, leading to bitter clashes with IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch.

Barry recorded in his application to the Military Pensions board that he had planned ‘big push’ with Lynch and Deasy in early 1923. Then Deasy ‘came out to us’, an Executive meeting was called and the Offensive cancelled. [24]

Barry later commented to the Free State officers who arrested him in late 1923 that ‘It was Deasy who put the tin hat on us’. ‘We were at the very highest levels of success. We captured three towns in Kilkenny, I personally organised Wexford, things looked most hopeful. The Deasy manifesto spoiled our morale and had more effect on our civilian backers’.[25]

Like, many of Barry’s pronouncements, this was an exaggeration. The anti-Treaty forces were already staggering in January 1923 from widespread arrests and terrorised by increasing numbers of executions (34 in January 1923 alone).

And it seems clear that Barry was already looking for ways to end the Civil War even before Deasy’s capture. All that said, Deasy’s call to surrender does appear to have been a watershed. In County Cork, from this point onwards, guerrilla activities dropped off sharply, with the first six months of 1923 showing a 75% decline in fatal violence compared to the last six months of 1922.[26]

Barry began to argue openly that anti-Treaty campaign, which he characterised as ‘senselessly sniping and shooting up towns’[27] was futile and should be called off. In this, he clashed bitterly with Liam Lynch, the Chief of Staff, who maintained obdurately, until the end, that the war could still be won.

Barry and Cork IRA officer Tom Crofts travelled to Dublin to meet Lynch in February 1923 to express ‘how bad things are in the south’. Already by this date, members of IRA GHQ were accusing Barry of ‘undermining the IRA’. It was reported by one Dublin officer that Barry, along with Dan Breen and some others, ‘want to surrender arms and have an election’. [28]

From this reading it may appear as if Barry was more flexible and pragmatic than Lynch, and to some extent this was true. Lynch has invariably been criticised for his stubbornness in continuing the guerrilla campaign long after it had lost any hope of victory. But there was also a clash of personalities involved between Lynch and Barry.

Tom Crofts recalled that Barry and Liam Lynch’s ‘dispute was of long standing’… ‘When we went up to Tipperary [for the Executive meeting] Barry was not talking to Lynch and things were very awkward. He [Barry] is a quick tempered man and it is hard to explain the dispute. It might be over taking a different route. I could never see why Barry and Lynch were not friends’. [29]

The IRA Director of Operations Bill Quirke thought; ‘Barry always wanted to do what he liked and resented having [to take] orders from anybody. I remember him and Lynch having some desperate rows, more or less over Barry’s surrender proposals…Barry said that we were beaten and there was no point carrying on. I think his proposal was to bury the arms or burn them or something like that’. [30]

While Todd Andrews, at that time acting as Lynch’s adjutant, recalled that, before the IRA Executive meeting in March 1923, Barry burst into his and Lynch’s safe house, indignant about Lynch’s order to withdraw from peace feelers. Barry, Andrews recalled, was ‘shouting angrily’ ‘Lynch did you write this?’ Yes. ‘I fought more in a week than you ever did in your life’. Lynch, according to Andrews, ‘simply said nothing’ and Barry left, slamming the door [31]

The minutes of the IRA Executive meetings in the dying days of the Civil War record Barry’s formal position. Arguing that Deasy’s surrender had made the situation hopeless, Barry proposed a motion that, ‘Further armed resistance to the Free State will not further the cause of the independence of the country’. The motion got the support of Barry’s comrades in Cork and Kerry, but was opposed by the Headquarters staff headed by Lynch and was defeated by one vote.

Liam Lynch was killed by pro-Treaty troops in the Knockmealdown mountains on 10 April 1923.

At a new Executive meeting April 20 1922, Barry proposed Frank Aiken as the new IRA Chief of Staff and he was duly elected. A motion was proposed to: ‘Empower the Army Council to make peace with the Free State “Government” on the basis of Ireland’s independence and territorial integrity.’ It was carried 9-2. Barry abstained.

He proposed ‘we direct the Army and [republican] government to call off armed resistance to the Free State’. It was defeated 9-2. A motion to carry on the war if the Free State rejected terms was tied 6-6 and the meeting adjourned. [32] As it was though, Aiken unilaterally called a ceasefire at the end of April and on May 24, ordered the IRA to ‘Dump Arms’.[33]

Although Barry had proposed Frank Aiken as Liam Lynch’s successor as IRA Chief of Staff, their relationship was to prove no more amicable than his and Lynch’s.

Aiken later recalled that, ‘I made up my mind when I became Chief of Staff that I was going to discipline Barry in the future. He treated Liam Lynch abominably and completely flouted his authority. If I was going to remain CS I was going to have complete authority from all’. [34]

Dying in Dublin

On the face of it, Barry’s argument that the Civil War needed to end, even if it involved the anti-Treatyites’ surrendering their arms, appears reasonable, more realistic in fact, than Liam Lynch’s insistence that the guerrilla war could still be won and closer to Eamon de Valera’s political strategy of the coming years.

However, when looked at in more detail, as they emerged in his acrimonious interview for a military pension in the late 1930s and 1940s, Barry’s proposals appear less pragmatic. On several occasions it appears that Barry, wanted, as a climax to the Civil War, a final sacrificial gesture in Dublin, reminiscent of the 1916 Rising.

As Barry later explained it to the pensions board, in April 1923 he ‘proposed that 200 of us go to Dublin and fight it out’. This would be a prelude to the end of the war and the surrender of arms, he argued.

Barry proposed that ‘Two hundred of us would go and raise the flag over O’Connell Street and fight with 50% casualties and then break up our arms and hand them in, the same as the men of 1916’.

‘Two hundred of us would go and raise the flag over O’Connell Street and fight with 50% casualties and then break up our arms and hand them in, the same as the men of 1916’. This, he reasoned, would redeem the honour of the Republican Army. After Liam Deasy’s surrender, according to Barry, ‘men were coming out of jail and making peace on us’. ‘The IRA fight was a bad fight, a disgraceful fight’… ‘There is no officer of the IRA proud of the fight in the second period [the Civil War]’. [35]

Barry seems to have made this argument more than once, recalling that after Lynch was killed on April 10 1923, ‘this debacle started’ with ‘men signing the form etc [surrendering]. We were sitting in a house in north Dublin and the first row started’. To ‘try to save what was left of this army’, Barry reiterated his proposal for a sacrificial action in Dublin. ‘We were beaten and that was the way to get out of it’. ‘200 men, fight for 2-3 days, then smash arms and surrender’.[36]

Bill Quirke when questioned on Barry’s position as the end of the Civil War also recalled the plan when questioned, ‘He suggested that 200 men should go to Dublin and then die?’

‘Yes he suggested that too. I remember that, since you mention it.’[37]

According to Meda Ryan , Barry tried to resurrect the idea in July 1923, after arms had been dumped and an IRA ceasefire called. With the IRA campaign over but their fighters still on the run and facing arrest, Barry proposed the destruction of arms in return for release of prisoners after a sacrificial, face-saving, assault on the Free State’s parliament at Leinster House. It would, according to Barry, be a ‘successful conclusion to the war from a republican point of view’, an honourable exit for our defeated force’.[38]

Resignation

The idea of a hopeless last stand in Dublin made sense to Barry’s sense of wounded military honour, but not to the IRA leadership, whose priority was, by the end of the Civil War, to avoid the complete destruction of their organisation.

Furthermore, the proposal to surrender IRA arms was, in the eyes of Aiken and others, mutiny, if not treachery. It was this, and his apparent encouragement of Volunteers to sign the form, recognising the legitimacy of the Free State and forswearing bearing arms against it, that finally snapped his relationship with Aiken.

He also continued contact with the pro-Treaty side. After the ceasefire, Barry, again on his own initiative, wrote to the Supreme Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, which since the Treaty split, was controlled by pro-Treatyites and now in 1923 deeply embedded in the high command of the National Army. Barry asked them to halt the ‘unnecessary and vindictive pursuit’ of IRA men who had dumped their arms.[39]

Frank Aiken forced Barry to resign from the IRA leadership, for his proposal that the IRA surrender their arms in July 1923.

Frank Aiken recalled that after the ceasefire in May 1923, Barry ‘tried to restart the Civil War’. Presumably this is a reference to Barry’s proposal for a final spectacular operation in Dublin. Then, according to Aiken, Barry advocated surrender, and ‘gave as a reason that all arms should be surrendered as the men could not stand the harassing they were getting [in July 1923]’. ‘He wanted at that time the complete and final surrender of arms and men’. [40]

Aiken considered this ‘a declaration of war’ on the authority of IRA GHQ. He forced the other officers, involved, including Tom Sullivan of Wexford and Tom Crofts of Cork to withdraw from the proposal and demanded Barry’s resignation and ‘he resigned’. [41]

On 11 July 1923, Barry was compelled to write a letter resigning from the IRA Army Executive, Army Council and as an officer of the IRA. In it, he denied that he wanted to compromise with the Free State, or to ‘abrogate the right of future armed resistance’, or that he had sought a compromise peace on his own.

These rumours were, he maintained ‘Absolutely false…. Lies, suspicion and distrust are broadcasted and I have no choice but to remove myself from any position…’ ‘I have never entered into any negotiations for a peace by compromise with the Free State’. He admitted a ‘technical breach of discipline’ but no more. And, ‘When arms are taken up again in a fight for the complete independence of Ireland, I will again be available for service.’ [42]

In Tom Croft’s recollection; ‘I think Barry wanted to hand up arms or something, as well as I remember… and leave everyone be arrested; fill up the gaols. We were beaten and let it be plainly seen we were beaten and every fellow go into gaol.’ According to Crofts the Southern Divisions were in favour, but Aiken and the Army Council were not. ‘Barry refused to withdraw it and Barry, in a temper, resigned.’

Frank Aiken maintained that Barry had resigned from the IRA altogether, but Barry’s position was that he had simply resigned from the IRA leadership. For Aiken, ‘It was clear in my mind that it was from the Army’. ‘He severed his connection from the Army but not from IRA members around the country’. [43]

A realignment?

While he had certainly lost his position of authority within the IRA, Barry still had to remain on the run, as he was wanted by the Free State authorities. When the IRA prisoners, several thousand strong, went on hunger strike in October 1923, Barry was dead against it and again clashed with Aiken. ‘We had at it’, he remembered. [44]

Barry himself was finally arrested in Cork city, with Tom Hales in December 1923, when they attempted to attend a meeting of Cork County Council. He was, however, to his surprise, released within a few hours after a friendly discussion with his captors. The pro-Treaty government did indeed, apparently, regard him as a peacemaker within what they termed the ‘irregular’ ranks.

Briefly arrested in December 1923, Barry voiced some sympathy with ‘the best elements’ of the Free State’s army, and hoped for a realignment based on hostility to partition

The National Army Intelligence reported to their political superiors on the conversation they had had with Barry during his brief period in custody. He was, they reported, ‘surprised at the decent way I was met’ upon arrest and surprised to be released so quickly. He was quick to acknowledge the republican defeat; ‘I did my level best to beat down the Free State government and army and failed’.

He appears to have been sympathetic to the former IRA element in the National Army – who at that time were on the verge of mutiny about their impending demobilisation and who were making noises about armed action against the government of Northern Ireland.

Barry told his captors, ‘Our only hope lies in best elements of your army … a very decent percentage of men in the Free State army are imbued with old ideal of free and independent Ireland and joined it with honest and patriotic motives… If a fight does come on for recovery of the six counties [Northern Ireland], I will gladly ally my forces those of the Free State.’ [45]

This was quite a break with republican orthodoxy. IRA Intelligence caught wind of Barry’s sympathy with the mutinous faction of the National Army, writing in January 1924 that ‘there is a move on the FS side to join up again, ‘all those sides who truly believe in the Republic’ is the usual formula…There are three groups; Free Staters proper, “Neutrals” and Tom Barry’s group… they plan a coup to seize the Army, seize [Government Minister Kevin] O’Higgins and pro-British FS groups and “proclaim the republic”.

The IRA leadership distrusted and wanted nothing to do with the National Army mutineers, but warned that ‘Tom Barry is very mercurial [i.e. unpredictable]’’.[46] Even at this late stage, however, Aiken appears to have offered Barry a senior position again within the IRA, presumably to try to control his activities.[47]

As it was, nothing came of the proposed coup, the Army mutiny of March 1924 turned out to be a damp squib and the mutineers were removed from the Free State’s military without bloodshed. The episode probably marked the final nail in the coffin of Barry’s republican career, however, as far as the IRA’s then leadership was concerned.

Epilogue

Tom Barry always denied that he left the IRA in 1923, and certainly there does not appear to have been clean break. He was present at Liam Deasy’s court martial in late 1923, for instance and successfully prevented the IRA from sentencing Deasy to death for his surrender in February 1923.

He rejoined the IRA, or at least resumed active service in it, in 1932, at a time when many who were senior in the IRA in 1923 were about to enter government in Fianna Fail, having won a general election in that year.

Initially, it seems, Barry’s motivation was the prospect of a possible war between the Irish state and Britain in light of the de Valera government’s stated aim to dismantle the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. This did not transpire, but a secondary motivation was to fight the Blueshirts, the pro-Treatyite street fighting organisation that had emerged from Army veterans to oppose Fianna Fail and the IRA.[48]

The disputes between Barry and Frank Aiken were refought with some bitterness in the press and on the Military Pensions Boards in the 1930s and 40s.

In subsequent years, however, Barry, again a senior IRA figure, also became a thorn in the side of the Fianna Fail government, especially after the de Valera government again began prosecuting the IRA, in 1934, having briefly legalised it in 1932.

Barry was convicted in front of the Military Tribunals, established to try the IRA, in 1934 for possession of arms and ammunition without permission and for contempt of the tribunal and given a 12-month sentence of imprisonment. In 1935, he did six more months in prison for membership of an illegal organisation and refusing to answer Garda questions as to his whereabouts.[49]

Also in 1935, he and Frank Aiken re-fought their bitter disagreements of 1923 in an acerbic exchange of letters in the national press. Aiken charged that ‘when the IRA was fighting and men were being executed in 1923, Tom Barry was running around the country trying to make peace.’ Barry shot back that Aiken had ‘avoided fighting’ in the Civil War ‘except on one occasion’ and that his ‘wobbling attitudes and refusal to take part in armed operations was mainly responsible for the republican defeat at that time’.[50]

When Barry applied for a military pension in 1938, due to his convictions in the 1930s, the Minister for Defence’s permission had to be sought for the granting of a pension. The minister concerned was Aiken and Barry’s pension application was the opportunity for some personal revenge on his and some of his colleagues’ part.

No one could deny that Barry had fought in both the War of Independence and Civil War, but every inconsistency in Barry’s application was ruthlessly pulled apart by often hostile witnesses. Barry himself was called in for three separate interviews by the Pensions Board over a period of two years. The file of his application eventually reached 245 pages. In 1940 he was eventually awarded a payment of 149 pounds per annum, payable from 1934.[51]

The myth of Tom Barry as legendary guerrilla fighter was forged in part from his actions as a fighter, especially in 1920 and 21, but also from his own accounts, particularly in his memoir Guerilla Days in Ireland, first published in 1949. The Civil War took up a mere three pages of ‘Guerrilla Days’ and detailed only his escape from Gormanston.[52]

The Civil War as a whole, let alone the bitter wrangling during it on the anti-Treaty side, was to play no part in the legend of Tom Barry.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] Much of this article comes from Barry’s Military Pension application, MSPC REF 57456, O’Malley’s testimony is on p.147

[2] See, Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish Civil War, Gill & MacMillan Dublin 2004, p. 64-65

[3] Barry MSPC

[4] Barry MSPC

[5] Anne Dolan, Cormac O’Malley No Surrender Here, the Civil War Papers of Ernie Omalley, p.29

[6] Reports to Executive Council IE/MA-CREC-01 General Military reports 1923-1924 16 Jan 1924 Office Director Intel

[7] Reports to Executive Council IE/MA-CREC-01 General Military reports 1923-1924 16 Jan 1924 Office Director Intel

[8] Per dressed as a nurse, this is Ernie O’Malley’s testimony, Barry MSPC

[9] Twomey papers UCD p69/77 CS-Eastern Div correspondence

[10] Anne Dolan, Cormac O’Malley, No Surrender Here, The Civil War papers of Ernie O’Malley, Lilliput Press, Dublin 2007, pp.174,194

[11] Dolan, O’Malley, No Surrender Here, p.250 EOM to CS 2 Oct 1922

[12] O’Malley testimony Barry MSPC

[13] Cabinet Minutes 16/10/1922, Re Ennis-Barry meeting.

[14] Ibid.

[15] See Barry and O’Malley testimony Barry MSPC, also O’Malley Dolan, No Surrender Here, p. 308 Ernie O’Malley to Robert Brennan (Publicity) 28 Oct 1922. ‘Tom Barry is not Dir Ops but is attached to Operations.’

[16] Irish Military archives CW/OPS/04/13 Reports from Cork

[17] Report 22 Nov 1922 CW/OPS/04/17

[18] Unpublished article by Niamh Hassett, Changing sides: Betrayal in Civil War.

[19] Ibid. Hassett, Changing sides: Betrayal in Civil War . I extend my thanks to Niamh Hassett for making her article and research available to me.

[20] According to Michael Harrington’s Munster Republic, p.110-112, Barry was also in command of a large assault of Millstreet in January 1923, but Barry makes no mention of this in his pension statement.

[21] De Valera papers UCD p150/1749 De Valera to Lynch 22 Dec 1923

[22] Irish Military Archives, Cork Command reports 18-19/12/1922 CW/OPS/04/17

[23] Gerard Shannon, Liam Lynch to Declare a Republic, Merrion Press, Newbridge, 2023 p.239

[24] Barry MSPC

[25] Irish Military Archives, Reports to Executive Council, IE/MA-CREC-01 General Military reports 1923-1924, 16 Jan 1924 Office Director Intelligence, Re Tom Barry

[26] See John Dorney, Casualties of the Civil War in Cork, The Irish Story, https://www.theirishstory.com/2019/07/14/casualties-of-the-irish-civil-war-in-county-cork/

[27] Irish Military Archives, Reports to Executive Council, IE/MA-CREC-01 General Military reports 1923-1924, 16 Jan 1924 Office Director Intelligence, Re Tom Barry

[28] De Valera papers UCD P150/1749, Lynch to de Valera Feb 22 1923

[29] Barry MSPC

[30] Bill Quirke testimony, Barry MSPC

[31] C.S. Andrews, Dublin Made Me, Lilliput Press, Dublin 2008, p.300-301

[32] De Valera Papers UCD P150/1739 IRA Exec meeting minutes, March 1923

[33] De Valera Papers UCD P150/1739 IRA Exec meeting minutes, March 1923

[34] Aiken testimony Barry MSPC

[35] Barry MSPC

[36] Barry MSPC

[37] Barry MSPC

[38] Meda Ryan, Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter, Mercier Press, Cork 2003, p.196

[39] Meda Ryan, Tom Barry, IRA Freedom Fighter, p.196

[40] Barry MSPC

[41] Barry MSPC

[42] Barry’s resignation letter is reproduced ins his MSP application

[43] Barry MSPC

[44] Barry MSPC

[45] Reports to Executive Council IE/MA-CREC-01 General Military reports 1923-1924 16 Jan 1924 Office Director Intel

[46] Twomey papers UCD, IRA Intelligence P69/81 DI to CS 21/1/1924

[47] Ryan, Tom Barry, p.199-200

[48] Ibid. p205-212

[49] Barry MSPC

[50] Ryan, Tom Barry, pp.213-215

[51] Ryan claims this was only 14 pounds, awarded in 1943 and that Barry, humiliated by his treatment at the hands of the pensions board, never claimed it. Tom Barry P.228. But in fact Barry’s pension file MSPC 34REF57456 shows that from August 1940 Barry was paid 149 pounds 7 shillings per year back dated to 1934, and that it was paid, including arrears, from that date. It was paid up to his death in 1980, except for a short period in 1974, when his pension was withheld in lieu of unpaid taxes.

[52] Tom Barry, Guerilla Days in Ireland, Anvil Dublin 1997, pp.229-231