When three American journalists visited ‘Paddy the Cope’ in Dungloe, 1919-1922

By Mark Holan

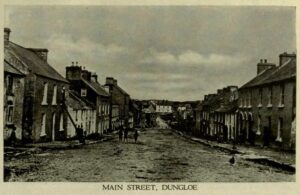

Dungloe (An Clochán Liath) in County Donegal is 170 miles northwest of Dublin, about a three-and-a-half-hour drive today.

The journey took much longer a century ago, when Dungloe was the penultimate stop on the Letterkenny to Burtonport extension of the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway. Dungloe station was an hour’s walk outside of town. But at least three American journalists trekked to the remote destination during Ireland’s dangerous revolutionary period.

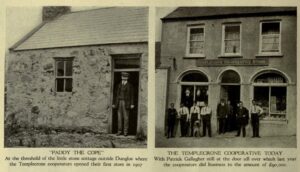

Paddy ‘The Cope’ Gallagher establihed an agricultural cooperative in Dungloe, Donegal in 1906 for locals to pool their resources and buy food and agricultural products more affordably.

They came to interview Patrick Gallagher, who organized the Templecrone Co-operative Agricultural Society Ltd., in 1906; the same year the rail service arrived. Known by the sobriquet “Paddy the Cope,” the latter word a popular abbreviation of “cooperative,” he persuaded locals to pool their resources to buy cheaper fertilizer.

Later, subscribers contributed funds to buy bulk staple goods such as tea, sugar, and eggs, which drew opposition from the usurious predators known as gombeen men, high interest shopkeepers and money lenders who enriched themselves while keeping local communities indebted and ignorant. Paddy organized women for a weaving and knitting business.

During the war of independence he shipped goods from Scotland and built a pier at Dungloe to overcome the brief British blockade of supplies to west Donegal in summer 1921, which created an uproar about starving the people.[1]

A December 1916 article in the New York Tribune was one of the first mentions of Gallagher in a US newspaper. Most of the story focused on George William Russell, the nationalist writer and artist known as AE. He and agricultural reformer Sir Horace Plunkett guided Gallagher in the cooperative concept. The Tribune attributed its information to The Irish Homestead, founded by Plunkett in 1895 and edited by Russell since 1905.

“The average farm paper is a prosaic thing,” the New York daily said, “but the Homestead is a revelation of wisdom and humor and beauty. Its editorials could be studied with profit in our (US) schools of journalism as models of English prose.”[2]

Good journalism also profits from independent, in-person reporting. As political violence and sectarian divisions escalated in Ireland, American reporters steamed across the Atlantic to investigate.

After all, this was the homeland of just over 1 million US immigrants and up to 20 million more Americans of Irish ancestry. These potential readers, if they did not have first-hand experiences of the Great Famine and the Land Wars, certainly had heard the stories of rural strife in Ireland from their parents and grandparents. Paddy the Cope’s successful cooperative in faraway Dungloe was a hopeful news story in the middle of another troubled time.

Ruth Russell

Ruth Russell appears to have been the first American journalist to visit Gallagher in Dungloe.[3]

The 30-year-old correspondent for the Chicago Daily News arrived in Ireland a week before St. Patrick’s Day, 1919. Her first story detailed the prison release and triumphal Dublin return of Countess Markievicz.[4] Russell interviewed Russell—AE, that is, no relation—at the Homestead’s Dublin office. He directed her to Gallagher.

“Patrick Gallagher is a successful Irish revolutionist,” Ruth Russell wrote in her dispatch for the Chicago daily, which syndicated the story to other US papers. “His is a revolution against poverty in the far northwest of Ireland. His plan is not bolshevist, for he does not want the people to take forcible possession of the industries, but he wants them to build up better ones than those that are privately controlled.”[5]

‘Patrick Gallagher is a successful Irish revolutionist. His is a revolution against poverty in the far northwest of Ireland.’ Ruth Russell

Russell probably drafted the dispatch from what AE told her. The story barely quotes Gallagher. But Russell wrote two later versions of her encounter with Gallagher, a May 1920 article for The Freeman, a progressive magazine, and a book, What’s the matter with Ireland?[6], which revealed more about the subject and the correspondent.

“When I saw Patrick Gallagher in Dungloe, he was dressed in a blue suit and a soft grey cap, and gave one the impression that if he had not been a co-operationist for Ireland he might have been a capitalist in America. He took me up the main street, making plain the signs of growing industry: the bacon cured in Dungloe, the egg-weighing, the rentable farm machinery. After viewing the orchard and beehives behind the cooperative store, I remarked on the size of the plant and its suitability for the purpose. ‘It used to belong to the gombeen man,’ said Paddy.”[7]

Russell also testified before the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland, the non-US government panel created by activists to keep Ireland in the news. She blamed mass emigration from Donegal on the change from tillage farming to cattle raising.

“Until the establishment of the cooperatives there, there were a great many Irish boys and girls who had to go either to America or migrate annually to the English and Scotch harvests,” she said. “By the establishment of the cooperatives there, not only the cooperative store but the cooperative bank and especially the cooperative knitting mill, a great many of the young people were enabled to stay at home.” Russell did not mention Gallagher in her testimony.[8]

Savel Zimand

Savel Zimand visited Gallagher in August 1921. In addition to his own reporting, Zimand solicited guest contributions from Irish political, business, and cultural leaders—including George Russell and Plunkett—for an all-Ireland special issue of Survey Graphic, a progressive journal focused on social issues.[9]

Zimand, a Romanian immigrant who obtained US citizenship 1919, also worked for the Bureau of Industrial Research, an offshoot of the Industrial Workers of the World. He also was 30 when he visited Ireland.

Zimand wrote:

“I arrived at Dungloe on a cold and rainy morning. And as the station is about three miles from the center of the village, I sent my luggage up by donkey cart and set out walking. Wild beauty was all around me. In ten minutes the rain stopped. The sky cleared and the wind freshened over the blue and golden hills. …

“(Dungloe) is a one-street village with little cabins surrounded by high hills and little silvern lakes with innumerable islands and the high sea. But what soil! Brown bog everywhere, grey rock and barrenness. Such green as there was cropped out among a million boulders. Only here and there are plots of potatoes about them. And hardly a tree to bind and shelter the earth. It was a wonder how people could live there. But they lived and prospered. And that was the wonder of Patrick Gallagher’s work. …

“I was tired with travel as I entered Gallagher’s door. The whole household was in the kitchen talking over the (Anglo-Irish) peace negotiations (in London). I shall never forget the hospitality with which I, a perfect stranger, was received by Patrick Gallagher and his family. ‘Paddy the Cope’ is a sturdy man in the prime of life. (He was nearing 51.) His appearance is that of a quiet, courageous fighter; but this fighter has proved to be an unusually successful manager. Over a bright turf fire he told me of his efforts to improve the lot of his people.”[10]

Like Russell’s stories, most of Zimand’s narrative focused on Paddy’s earlier success at breaking the grip of the gombeen men. But Zimand also addressed the British military’s recent blockade of west Donegal by closing the railway, and Paddy’s effort to sail in supplies from Scotland.

As Irish plenipotentiaries and the British government negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the New York Globe and the New York Call interviewed Zimand about Irish politics. Zimand commented about the “wonderfully developed” cooperative movement in Ireland, but he did not mention Gallagher before his own story appeared in Survey Graphic. Zimand’s papers at the University of Minnesota do not contain material about Gallagher or Dungloe.[11]

Redfern Mason

In summer 1922, Redfern Mason of the San Francisco Examiner tossed his “portmanteau and typewriter” into a “side cart” stuffed with mail, newspapers, animal feed, and other cargo. He had reached Fintown on the Donegal Railway instead of the more northerly “Swilley” line extension to Dungloe, likely because of ongoing rail disruptions from the civil war.[12]

“It was a heavy load and we tottered and lumbered through thirteen miles of the wildest country in Donegal,” Mason, then 55, wrote of his ride to Dungloe.[13]

He was a native of Manchester, England, who had emigrated to America and became naturalized in 1906 at age 22. He began his newspaper career at the Rochester (N.Y.) Post-Express, then headed west to become music critic at the Examiner. He published The Song Lore of Ireland: Erin’s story in music and verse in 1911.[14] Mason spent two months in Ireland as anti- and pro-treaty forces fought over the fledgling Free State.

Upon his arrival in Dungloe, the correspondent was shown to the cooperative store, which he described as “for all the world like the typical general store in an American country town, though rather larger.” He found Gallagher in his office, “a middle-aged man, solidly built, with a round clean-shaven face that dimples with a shrewd good humor.”[15]

Mason published 18 installments of his “On Tour of Ireland” series in the Examiner during September and October 1922.[16] He also gave local lectures about his experiences.[17] At the time, San Francisco was the largest Irish hub on the US West Coast.

The following year Mason self-published a booklet, Rebel Ireland, about his adventures. He devoted 10 of its 63 pages to his day-long meeting with Gallagher. The host told the visitor that funding for the Dungloe pier came from America.[18] Mason described the cooperative as “a tale to give new wings to hope. … What has been done in Donegal can be done all over Ireland.”[19]

Other views

Irish writer Shaw Desmond reached a slightly different conclusion about cooperatives in a 1922 op-ed for the New York Herald.

“I prophesy that before fifty years are out Ireland will be covered partly by a network of cooperation and partly be large stores and factories run chiefly on American capital, which, competing with the ‘co-ops’ for the business of Ireland, will help to keep the latter from getting self-satisfied and rusty,” Desmond declared.[20] The opinion piece had no source attribution or indication that Desmond had ever visited Dungloe.

“I prophesy that before fifty years are out Ireland will be covered partly by a network of cooperation and partly be large stores and factories run chiefly on American capital, Shaw Desmond, 1922

Beyond the pages of the Homestead, other Irish papers also detailed Gallagher during the revolutionary period. Writing under Aodh Sandrach de Blácam in the Irish Independent, the English-born Harold Saunders Blackham described Paddy as “the biggest man in Ulster,” meaning the most consequential, yet one that visitors would find “just a plain specimen of the northern iron. … The secret of his success is his flaming energy and his democratic hand in every detail.”[21]

The three American correspondents were not Gallagher’s only foreign visitors. Ibrahim Rashad, a young leader in the Egyptian cooperative movement journeyed to Dungloe in 1919. His visit, part of the wider post-First World War anti-colonial awakening, came after both Ireland and Egypt were snubbed at the Paris peace conference. Rashad also spent time with Russell and Plunkett, then published the 1920 book, An Egyptian in Ireland.

“The journalist who comes for a week or fortnight confines himself to political issues, and when he has interviewed a few leaders he goes away thinking he understands the Irish question,” the Irish writer and poet Susan L. Mitchell, AE’s colleague at the Homestead, wrote in the preface. “The more philosophic mind realizes that politics depend largely on economics, and that it is the social order and the average daily life of men that we must examine if we would understand the national being and the ideals of the people. Ibrahim Rashad has gone to fundamentals.”[22]

In fairness, Ruth Russell and Mason also wrote about Irish economic and social issues beyond Dungloe. She lived briefly in the Dublin slums and applied for hard-to-find jobs with other women. She reported from the Limerick soviet.

Gallagher died in 1966, but the cooperative enterprise he began sixty years earlier thrives today

He interviewed the head of the Dublin Industrial Development Association on how Irish cities could apply science to avoid the pitfalls of urban squalor in manufacturing centers such as Manchester and Birmingham, in England; and Pittsburgh and Chicago, in America. In addition to contributions from AE and Plunkett, Zimand obtained guest essays on industrial and labor policies; healthcare; education; and women’s equality for the special edition of Survey Graphic.

Gallagher published his autobiography in 1939. An American edition appeared three years later. Paddy recalled that he bought special insurance for the cooperative store to cover potential damage from military destruction during the war. One of the Dáil Courts convened at Dungloe.[23]

“From 1918 to 1921 I had a miserable time of it,” Gallagher wrote. “The Black and Tans were worse than savages let loose. They were murdering, ravishing and burning.”[24]

Gallagher credited the help he received from Russell and Plunkett and acknowledged “important visits from people who were interested in the co-operative movement up here on the top of Ireland, amidst the bogs and rocks.” He named Zimand and Rashad, among others.[25]

Gallagher died in 1966, but the cooperative enterprise he began sixty years earlier thrives today. It has expanded into 12 retail businesses in four locations: Dungloe, Annagry, Kincasslagh, and Falcarragh. “The Cope” can even be reached online, for those who can’t travel to Donegal.

Mark Holan writes about Irish history and contemporary issues at markholan.org.

References

[1] Diarmaid Ferriter, “Gallaher, Patrick”, in the online Dictionary of Irish Biography, October 2009. Also see Note 24.

[2] “Sweepings From Inkpot Alley”, New York Tribune, December 17, 1916. The story was bylined “Tansy M’Nab,” probably a pseudonym. The Homestead ceased publication in 1918, was revived in 1921, then merged with the Irish Statesman in 1923.

[3] The American journalist William Henry Hurlbert visited Dungloe in 1888. See “An American Journalist in Ireland Meets Michael Davitt & Arthur Balfour”, The Irish Story, Sept. 13, 2018.)

[4] See “Ruth Russell in Revolutionary Ireland”, The Irish Story, January 8, 2020.

[5] “Revolution Aimed At Irish Poverty”, Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), August 19, 1919, via Chicago Daily News.

[6] “Building The Commonwealth”, The Freeman, May 26, 1920, and Ruth Russell, What’s the matter with Ireland? [New York: Devin-Adain, 1920].

[7] From the Freeman. The book version is slightly more detailed.

[8] December 15, 1920, testimony of Ruth Russell, found in Evidence on Conditions in Ireland, Transcribed and Annotated by Albert Coyle. [Washington, D.C., 1921] 448.

[9] See “When a US magazine devoted a full issue to Ireland”, markholan.org, January 21, 2025.

[10] “The Romance of Templecrone”, Survey Graphic, November 26, 1921.

[11] Quote from “Dominion Rule Would Lead Ireland To Unity, Declares Investigator”, New York Globe, September 9, 1921. Also “Irish People Want Peace, but Won’t Yield Inch To British”, New York Call, October 7, 1921, and other material related to the Ireland trip in Savel Zimand papers, Social Welfare History Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. Digital copies of requested material provided to the author by email, November 1, 2024.

[12] Mason refers to war-related disruptions of the Irish railways system in “A Journey to Kerry”, San Francisco Examiner, October 9, 1922. Also see “When Donegal had trains! – The Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company”, The Irish Story, December 3, 2022.

[13] “An Irish Cooperative”, San Francisco Examiner, September 22, 1922.

[14] “Former Music Critic, Redfern Mason, Dies”, San Francisco Examiner, April 17, 1941; Mason’s 1922 passport application at National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications: Chicago, New York City, New Orleans, San Francisco and Seattle, 1914-1925; Volume #: Volume 7: Special Series – San Francisco.

[15] “An Irish Cooperative”, San Francisco Examiner, September 22, 1922.

[16] “25 Years Change Dublin, Mason Says”, Sept. 10; “Was Ever Such War Since World Began”, Sept. 17; “Ireland Needs Industry,” Sept. 20; “An Ancient House”, Sept. 21; “The Art of New Ireland”, Sept. 22; “In An Irish Village”, Sept. 23; “An Irish Abbey”, Sept. 26; “An Irish Co-Operative”, Sept. 29; “Pilgrams To Glendaloch”, Sept. 30; “A Journey to Kerry, I”, Oct. 9; “A Journey to Kerry, II”, Oct. 10; “Pictures of Kerry”, Oct. 11; “In An Irish Cottage”, Oct. 12; “At Ballyferriter”, Oct. 13; “An Antique World”, Oct. 14; “An Irish Innkeeper”, Oct. 17; “A Sunday Drive”, Oct. 18; and “The Departure”, Oct. 19. All stories in the San Francisco Examiner, accessed at Newspapers.com. Mason wrote additional articles about his 1922 travels in other parts of Europe.

[17] “Redfern Mason To Lecture On Ireland”, San Francisco Examiner, October 29, 1922.

[18] Dungloe received £256 in “personal relief” from the Irish White Cross as part of the $5 million collected by the American Committee for Relief in Ireland in 1921. Donegal county received £4,832 in personal relief. Report of the Irish White Cross, [New York: American Committee for Relief in Ireland, 1922], Appendix D: “Geographical Distribution of Personal Relief to the 31st August, 1922”, 88. Appendix E shows £2,175 in “reconstruction commission” funding for the entire county, 101. No details of the pier project are found in report. Gallagher uses the figure £6,000 in his autobiography. See Note 24.

[19] Redfern Mason, Rebel Ireland. [San Francisco: Published by the author, 1923], 47, 57.

[20] “American Capital Has Great Field In Ireland”, New York Herald, July 30, 1922.

[21] “Home Industries”, Irish Independent, October 31, 1919.

[22] Susan L. Mitchell preface, ix, in Ibrahim Rashad, An Egyptian In Ireland. [Privately printed for the author, 1920].

[23] “The Rise and Fall of the Dáil Courts, 1919-1922”, The Irish Story, July 25, 2019.

[24] Patrick Gallagher, Paddy the Cope. [New York: Devin-Adair, 1942.], 210. He discussed the blockade and the pier on pages 215-219. (Originally published as My story, by Paddy the Cope. [London: Jonathan Cape, 1939].)

[25] Ibid, 260.