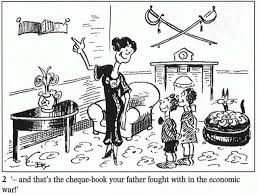

The Economic War, 1932-38

By John Dorney

In 2025, the world has once again become acutely aware of the use of tariffs as an instrument of economic and political coercion. At the time of writing (March 2025) the United States’ president has imposed draconian tariffs on imports to that country, both from rivals such as China and erstwhile allies such as Canada and Mexico. Further punitive tariffs are promised on the European Union.

What parallels can be drawn from Ireland’s past?

There are a number of famous instances of trade wars in Irish history. In the eighteenth century, an Irish Protestant cleric and writer Joanathan Swift urged his countrymen to ‘burn everything English except their coal’. Later in that century, Irish ‘Patriots’ (their term) rallied armed and uniformed in Dublin and pointing to a cannon, demanded of the British government, ‘Free trade or this’.

But the most relevant parallel to current events in Irish history is the so-called ‘economic war’ of the 1930s between the new Irish state and Great Britain.

‘War’ breaks out

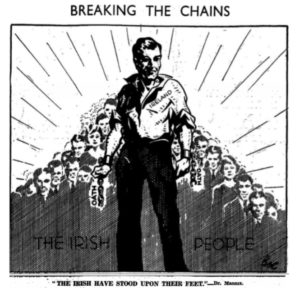

After the Irish general election of 1932, the new Fianna Fáil government of Eamon de Valera came to power, with the support of the Labour Party, pledging to dismantle the limits placed upon Irish independence by the Anglo- Irish Treaty of 1921. It was against this Treaty that de Valera and his colleagues had fought a Civil War in 1922-23. Once in government, they abolished the Oath of Fidelity to the British monarch, the position of Governor General (representative of the monarch) and for its opposition to these changes, the Senate of the Free State.

They also refused to pay ‘land annuities’ owed to Britain under the Treaty of 1921. These were payments dating from the Land Acts of the first decade of the century, in which the British government had subsidised the purchase of land by tenant farmers from the old landlord class. The Land Annuities amounted to over 100 millions pounds and annual payment to about 5 million, which the Fianna Fáil government argued was not only unfair but a bigger per capita burden than the reparations owed by Germany to the Allied powers after the Treaty of Versailles.[1]

Withholding the annuities was also good politics on de Valera’s part. A popular campaign by left-republican Peadar O’Donnell and elements of the IRA had urged small farmers not to pay the annuities owed to the British and by the time de Valera assumed office, many were not paying. Thus, as well dismantling an objectionable aspect of the Treaty, de Valera was also preventing Fianna Fail from being outflanked by more radical republicans on his left.

The response of the British government was also primarily political rather than economic in motivation. They believed that they had created a loyal Dominion in the Irish Free State and that a ‘moderate majority’ of Irish voters there favoured a conciliatory, pro-Treaty line.

The British thus looked aghast at de Valera entering government, viewing him as the arch radical of 1922 and perhaps also as ‘an Irish Kerensky’ who would allow a takeover by the IRA or even by ‘Bolsheviks’.[2] It was their hope that economic pressure in the form of a trade war would destabilise the Fianna Fáil government and bring back into government the more congenial pro-Treatyites of Cumann na nGaedhal. British ministers thought that a ‘short sharp campaign’ of ‘purely temporary’ tariffs would result in the election of a new government’ in the Irish Free State.[3]

In retaliation, then to the withholding of annuities, but also to punish the de Valera government, the British government placed punitive tariffs of 20 per cent on Irish agricultural imports and also placed a quota on how many Irish cattle which could be imported into Britain. The idea that economic pressure can bring quick political results is still current today. But like many an actual war, the economic war was neither quick, nor painless, nor did it result in a British victory. Also like an actual war, once underway, it escalated.

In 1934 British tariffs were raised to 30 per cent on Irish agricultural goods and tariffs on the import of Irish cattle to Britain was raised to a prohibitive 88 per cent.[4] At this time, the greater part of the Irish Free State’s economy was agricultural and the vast majority of its exports were to Britain.

Nevertheless the de Valera government was not cowed and retaliated by placing tariffs on British industrial imports, particularly on coal, iron and steel. By 1936, the average tariff on goods travelling between the Irish Free State and Great Britain had risen from 9 per cent to 45 per cent.[5]

Far from hurting the de Valera government, however, standing up to the British proved to be very popular among the Irish electorate. In a snap election called in 1933, Fianna Fáil were returned to government, but this time with an overall majority, increasing its share of the cote from 44 to 49 per cent. British policy makers noted that de Valera had got ‘immense political milage out of the economic war’.[6]

Part of the reason for Fianna Fáil’s dogged defiance was that fighting the economic war dovetailed with their agenda of economic nationalism. In the context of the Great Depression, many countries, beginning with the United States in 1930, had begun erecting trade barriers to protect their economies. Global trade volume fell by 25 percent between 1929 and 1933, with nearly half of this decline attributable to higher trade barriers. [7]

Fianna Fáil hoped, behind a wall of tariffs, to build an indigenous Irish industrial base, to reduce unemployment and stem the flow emigration from the country. This was a marked break with their predecessors in government, Cumman na nGaedheal, who had favoured relying on agricultural exports, low trade barriers and little government intervention.

In 1932 Sean Lemass, then a firebrand economic nationalist and Fianna Fáil minister, wrote that ‘we believe Ireland can be made a self-contained unit, providing all the necessities of living in adequate quantities for all the people residing in the island at the moment and probably for a much larger number’.[8]

And behind the tariff wall, or to get around it, a manufacturing base did emerge, albeit mostly to serve the domestic market. At the same they set up a series of semi-state companies such Irish Sugar, the Irish Turf Board or Bord na Mona, a national airline, Aer Lingus, and others.

They also passed a law, the Control of Manufactures Act 1934, which stated that all companies locating in Ireland had to have 51 per cent Irish ownership two thirds of Irish members of on its board.[9]

It was remarked that by the mid 1930s, there had been the first increase in industrial employment in Ireland since the mid 19th century, of over 40,000 new jobs. Some of the money raised from tariffs and an increase in internal trade, was used to build social housing and to redistribute land via the newly formed Land Commission.[10]

They did not however, stem emigration to a great extent.

Class Warfare

If de Valera’s political and economic policies were popular with sections of the electorate, among others, those, mostly farmers, directly impacted by the decline of trade with Britain, they aroused fury. Some farm incomes fell by a s much as half and the numbers working in agriculture fell considerably. The newly formed Fine Gael party (a merger of Cumman na nGaedheal and several smaller parties) pilloried de Valera’s policy in parliament.

Anger among farmers was exacerbated as the Irish government continued to collect land annuities for its own use and if farmers refused to pay, seizing their cattle and selling them at auction. Some of cattle were slaughtered and free meat distributed to small farmers and the poor. Ultimately more than 200,000 cattle were seized from farmers who could not or would not continue to pay the annuities during the economic war.[11]

The discontent so caused helped to spark the most serious political violence that the Free State had seen since the end of the Civil War in 1923. The farmers’ case was taken up by the militant pro-Treaty grouping, the Blueshirts, originally the Army Comrades Association, led by former Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy, who had been sacked by de Valera. The Blueshirts, with their uniform and stiff-armed salute, took on a least the trappings of fascism and like the hard right elsewhere in Europe, painted themselves as a bulwark against social revolution. De Valera in turn recruited former IRA members into the Gardaí, including an armed formation known as ‘Broy’s Harriers’.

Demonstrations against cattle seizures often ended with riots between the Blueshirts, republicans and the Gardaí. In one incident in Cork city, a Blueshirt (and farmer) Michael Lynch was shot dead by Gardaí after the Blueshirts had used a lorry to ram the gates of a yard where seized cattle were impounded. [12]

In some areas, the Blueshirts, whose activities historian John Regan characterises by this time as mostly ‘agrarian protest’ were engaged in what almost amounted to a guerrilla war against state policies, blocking roads, felling telephone lines and often engaging in rioting and sometimes even shooting. [13]

While this violence, on the face of it, had little to do with the constitutional issues that had sparked the Civil War in 1922, in fact there was some continuity. The pro-Treaty government of that time had used troops, some organised in a Special Infantry Corps, to collect rents, smash strikes of farm labourers and end land occupations in the interest of the big farming and grazier class.

Now it was the same big farming class, the social bedrock of pro-Treaty support, that suffered under Fianna Fáil policies, which were perceived to benefit its supporters among the poor farmers and urban poor. It was this, much less bloody, social conflict of the 1930s, more than the actual Civil War, that built up the basis of what came to be called ‘Civil War politics’ in Ireland.

As Kevin O’Rourke notes, the 1933 election was the first time that Fianna Fáil had won Dublin, largely because the effect of the economic war and protectionist policies had been to ‘redistribute income from rural to urban areas.’ And while prosperous farmers were hurt by the policies of the de Valera government, the provision of some forms of welfare and land re-distribution consolidated Fianna Fáil’s base among the rural poor.[14]

Ending the Economic War

By the mid 1930s, the British had worked out that economic pressure would not oust the de Valera government. Nor was he turning out to be the radical they had feared. Meanwhile trade war was hurting both sides, especially cattle farmers in Ireland coal producers in Wales. [15]

Some agreement was worked out in 1935, in which the British agreed to relax tariffs on imported Irish cattle in return for the relaxing of tariffs on coal.

This eased the situation of Irish farmers and along with Fine Gael, after some flirtation, stepping back from backing Blueshirt-related violence, helped to calm tempers in Ireland itself.

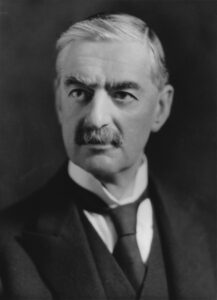

However, a final settlement was not reached until 1938. This turned out to be much more wide-ranging agreement than merely economic. As well as both sides restoring tariffs to a low level, they agreed to settle the outstanding debt for the land annuities, which stood at over 100 million pounds, for a mere ten million.

Even more importantly, Britain returned the three Atlantic naval ports it had retained since 1921 and gave up the clause in the Anglo-Irish Treaty under which the Irish state had to give up all its ports ‘in time of war’. This represented a major victory for de Valera.

On the part of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, this climbdown was, again, more of a political than an economic policy. It was hoped, in the light of a looming European war with Nazi Germany, to repair relations with the Irish state (known after de Valera’s new constitution in 1937 as Éire) and to secure their aid (vainly, as it turned out) in the event of new war.

Perhaps, as Kevin O’Rourke argues, de Valera was ‘simply lucky’. Chamberlain needed a deal and proved far more yielding than his successor as Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

But for Fianna Fáil the economic war was viewed at the time as a triumph. Sean Lemass stated that it did not matter who had started the trade war, ‘the main thing is, we won it’.[16]

Assessments

Economic historian Cormac Ó Gráda remarks that the economic war ‘was a phoney war, no blood spilt, no diplomatic relations severed,’[17] but it was nonetheless a formative period in the development of the Irish state and its politics.

The Irish state remained tied to Britain in many ways, notably by its currency, but the Economic War went some way towards demonstrating Irish political and economic independence.

It also re-opened and deepened internal antagonisms first opened by the Civil War of 1922-23.

By the late 1950s, the economic policies of de Valera’s government were widely seen as having failed. Since the 1960s, but especially since the 1990s, the economic policies of the Irish state have favoured free trade and advertising the country as a base for foreign investment.

This has, of course, coincided with a great wave of international economic globalisation, of free trade and lowering of trade barriers. As a result, estimations of Ireland’s experiment with protectionism and economic nationalism have generally been negative, perhaps too negative, and judgements of the economic war too ruinous.

In Cormac Ó Gráda’s judgement, the ‘economic war’ hurt the Irish agricultural economy only marginally more than the concurrent Great Depression would have anyway. Virtually all states were erecting tariff walls and quotas in order to protect domestic producers and Britain was no different.[18] Assessing other countries which were also primarily exporters of livestock to Britin, including Denmark, New Zealand and Canada, O’Rourke finds that the Irish state fared somewhat worse than Dominion countries but no worse than a non-Dominion like Denmark.[19]

Contrary to later orthodoxy, Cormac Ó Gráda also concludes that Fianna Fáil’ strategy of developing Irish industry by protectionism had some success in terms of rising income and overall welfare of its citizens, which offset the pain caused, especially to the farming sector, by the economic war. Though he also comments that industry dependent on tariff walls was particularly open to favouritism and corruption in favour of the friends of the ruling party. [20]

Who needed to build businesses that were competitive and innovative, if one could secure a near domestic monopoly due to political contacts and tariff walls?

Further to the left, Conor McCabe’s criticism of the de Valera government was that it did not go far enough in breaking the stronghold which, he writes vested interests such as ‘cattle ranching’ and banking had over the economy of independent Ireland. McCabe writes that the Free State was unusual in the 1930s, not in engaging in tariff wars to build up its industry but in ‘deciding to fight one fiscal arm behind its back’, in choosing not to create an Irish central bank or independent currency. In the 1930s all these things still lay in the future.[21]

So what are the lessons today from the Anglo-Irish economic war of the 1930s? In recent decades, most economists and historians would have responded unhesitatingly that the lesson was simply that trade wars, and state protection of industry through tariff walls, was harmful, especially for a small country like Ireland, and should be avoided.

But in a world again be riven by great power rivalry, both political and economic and even military, this may no longer be as clear cut. Ireland cannot be an island of free trade in a protectionist sea. Ireland’s economic choices may not be hers to make.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing to our Patreon page for The Irish Story if you would like to support our work.

References

[1] Cormac O Grada, Ireland, A New Economic History, 1780-1939, (Oxford 2001), p.411

[2] Kerensky was the Russian revolutionary leader who headed the Provisional government founded by the February 1917 revolution which overthrew the Tsar but who was himself ousted by the Bolsheviks or communists in October of that year.

[3] Paul McMahon, British Spies and Irish Rebels, p.233 (Boydell 2011)

[4] Gerard McCann, Ireland’s Economic History p.89-90, see also, Kevin O;Rourke, ‘Burn Everything English Except their Coal’, The Anglo Irish Economic War of the 1930s, Journal of Economic History, Vol 51 no 2, 1991, p.357-366.

[5] McCann, p.90

[6] McMahon, p.234

[7] Christian Henn and Brad McDonald, Avoiding Protectionism, Finance & Development, March 2010, Volume 47, Number 1, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2010/03/henn.htm

[8] O Grada, p.406

[9] Conor McCabe, Sins of the Father, Tracing the Decisions that shaped the Irish Economy, The History Press, 2011, p.77

[10] McCabe, p.77-79

[11] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy,a Self Made Hero, p.261

[12] Ibid, p.262

[13] John Regan the Irish Counter Revolution, p.360-361

[14] O’Rourke, Burn Everything English

[15] O Grada, p. 413

[16] O Grada p.432

[17] Cormac O Grada, Ireland, A New Economic History, 1780-1939, (Oxford 2001), p.411

[18] O Grada, p.412-13

[19] O’Rourke, Burn Everything English

[20] O Grada p.433

[21] McCabe, Sins of the Father, p.76