Attorney General versus Tom Barry: The Curious Tale of Tom and the Tommy Gun

By Aaron Ó Maonaigh

On 4 May 1934 the contemporary press reported that Thomas ‘Tom’ Barry, ‘one of the most famed and colourful guerrilla fighters of the Anglo-Irish war’, had been tried and sentenced to one year’s imprisonment for possession of a firearm. What the press failed to report was that the fireman found at Barry’s home was no ordinary weapon but an iconic and evocative symbol of the revolutionary era, a Thompson sub-machine gun.

Barry’s case is an intriguing one, not solely due to the presence of a Tommy gun, but for the raison d’être for the searching of the revolutionary veteran’s home which reveals a fascinating insight into the prevailing turmoil and tensions that simmered beneath the surface of Irish political life. The curious tale of Tom Barry and his Thompson gun features the quasi-fascist paramilitary organisation the Blueshirts (ACA), the clandestine Garda unit, ‘Broy’s Harriers’, and murder in West Cork.

In late 1920 IRA agents in the United States secured a deal to purchase several hundred Thompson sub-machine guns with the intent of smuggling the recently developed weapons into Ireland. The deal was effected by the republican emissary in the US, Harry Boland, and financed with Irish republican money which was channelled through Thomas Fortune Ryan, a senior figure in the Irish-American support group, Clan na Gael.

Unluckily for the IRA, on the eve of their exportation on 16 June 1921 a consignment containing 495 of the 653 guns ordered were impounded aboard the SS Eastside by US Customs agents at Hoboken Harbour, New Jersey. The remaining 158 guns were eventually smuggled to Ireland mainly after the Truce. However, at least two early models of the gun were smuggled into Dublin before the climax of the Anglo-Irish war by Irish-American military officers.

These guns received their combat debut during an ambush of a troop special train carrying British military at Drumcondra, coincidentally on the same day as the seizure at Hoboken. The Eastside’s discovery shattered any hopes of a countrywide dispersion of the guns as proposed by IRA GHQ, and its use during the latter stages of the Anglo-Irish war was limited to a handful of operations in counties Dublin and Kildare. The gun saw much more use during the subsequent civil war, particularly on the part of the Republican or anti-Treaty side.

How Tom Barry came to possess a Tommy gun, is likely a result of the successful court case taken against the US authorities by representatives of Clan na Gael in the aftermath of the Eastside debacle. By law it was not illegal to own several hundred machine guns in the United States and so after much legal wrangling, the 158 impounded submachine guns, replete with thousands of rounds of ammunition, were finally released in September 1925 to Joseph McGarrity who secretly exported the guns to Ireland throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

In his role as general superintendant at Cork Harbour Commissioners, Barry personally oversaw the importation of a number of Tommy guns and ammunition from the requisitioned Eastside consignment to Cork in the early 1930s. It is not unreasonable to assume that the gun found at Barry’s home on 4 April 1934 was a keepsake from the Eastside lot. When the Gardaí searched Barry’s home their purpose was not to retrieve the Thompson, however, the discovery of the gun offered the authorities an opportunity to effect their true motive, to arrest and question Barry regarding the alleged murder of a young man in West Cork which occurred some months prior.

‘No free speech for traitors’

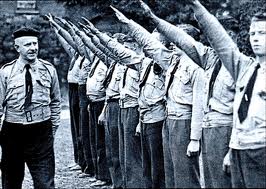

In February 1933 Taoiseach Éamon de Valera fired General O’Duffy and Éamonn ‘Ned’ Broy succeeded O’Duffy as Garda Commissioner; O’Duffy assumed the leadership of the Blueshirts. Upon his succession to Commissioner, Broy set up an armed auxiliary force that consisted of former anti-Treaty IRA men and Fianna Fáil supporters. This hastily formed special unit of the Gardaí – dubbed ‘Broy’s Harriers’ – took up duty with little or no formal training and immediately set about tackling the bellicose Blueshirts.

The period between 1933 and 1935 saw the old antagonisms of the Civil War played out writ small as the Army Comrades Association – aka the Blueshirts – and the IRA clashed at regular intervals in towns and villages around the country. The IRA – at this time loosely aligned with Éamon de Valera’s Fianna Fáil party – was legalised by the government and its members began attacking individuals associated with Cumann na nGaedheal and the Blueshirt organisations, and breaking up rallies of same under a slogan of, ‘no free speech for traitors’.

To the conscious observer it appeared as if physical revenge for the republicans’ defeat in the Irish Civil War was a likely prospect. Initially, Broy’s unit took a benevolently ignorant stance with regard to IRA activity, focusing instead on quashing the Blueshirt movement. However, as friction between Fianna Fáil and the IRA leadership emerged the unit began to focus its attentions on active Republican dissenters.

In County Cork tensions between those aligned with the IRA and the Blueshirts raged, manifesting in numerous, sporadic beatings and assaults throughout the winter of 1933 and spring 1934. A confidential memo originating from the office of the Deputy Commissioner Éamonn Coogan reveals that the pretence under which the search on Barry’s home was conducted was based on Garda suspicions of Tom Barry’s involvement in one such attack.

On the night of 28/29 October 1933 the homes of John O’Leary and John O’Reilly, farmers in the Bandon area, were visited by armed and masked men who committed a vicious assault upon Denis O’Leary and Hugh O’Reilly, young men known to be active members of the Blueshirts and sons respectively of John O’Leary and John O’Reilly.

Hugh O’Reilly died subsequently as a result of the beating he received, and at the coroner’s inquest a verdict of murder by some person or persons unknown was returned. Following a tip-off from an unnamed informant, Gardaí investigating the death of O’Reilly believed the incident to have been a reprisal for an alleged Blueshirt assault on Denis O’Connor, a member of the IRA and native of Innishannon, which occurred one week prior.

Chief Superintendent Michael Fitzgerald reported that an informant told him that on 27 October 1933 Tom Barry showed him a report of the alleged attack on O’Connor, who claimed he was taken from his home, stripped and beaten for several hours by associates of the Blueshirts. The informant stated that Barry was incensed by the assault on O’Connor and told him that he planned to do a ‘frightful thing’ in retaliation.

The case attracted considerable attention from Deputy Commissioner Éamonn Coogan, who had Chief Superintendent W.J. Stack of Cork City take over the investigation from Fitzgerald and encouraged him to take a close look at Barry’s involvement. Coogan was eager to have the matter fully investigated, and claimed in a memo dated 12 January 1934 that ‘Barry was known to the Police to have made use of certain threats of reprisals, which showed evidence of intention on his part’.

Despite repeated calls on the part of Coogan to bring Barry in for questioning, Stack thought it inadvisable, as interrogating him in relation to this incident and the alleged threat of reprisal would have serious repercussions for the Gardaí’s unnamed informant.

Fitzgerald argued, the informant proffered his information ‘in confidence… and the divulging of it is likely to have very serious results’. Stack also argued it was inexpedient to interrogate Barry as he ‘would refuse to divulge anything on interrogation’, and ‘No useful purpose would be served by interrogating him —at least at this stage’.

Stack wrote again to Coogan on 16 January promising ‘a more comprehensive report’ to be submitted within in the week. True to his word, Stack reported back to Coogan on 18 January and explained that the Gardaí, having exonerated three previous suspects, now believed that Tom Barry and four others — Seán Mitchell, Charles McCarthy, Standish Barry and Christopher Aherne from various parts of Cork City— of being main culprits in the murder investigation.

‘In view of this there can be no reason why those persons should not be closely questioned… [and] their houses searched’, Coogan responded on 21 March. All of the men’s homes were searched on 4 April, but nothing was found linking any of them to the crime.

However a Thompson sub-machine gun was found at the home of Tom Barry, in addition to 384 rounds of ammunition. Although the Gardaí failed to find any concrete evidence linking Barry to O’Reilly’s murder, the discovery of the Thompson gun afforded the Gardaí the opportunity to formally arrest him for possession of an illegal weapon. On 18 April Barry was arrested at his workplace, Union Quay, Cork. As expected, he declined to accept responsibility for the gun’s ownership and refused to answer any questions.

‘Take this message from me to Deputy Commissioner Coogan that I know of his anxiety to arrest me for the past six months’

Barry was brought before a Military Tribunal, at Collins’ Barracks, Dublin, on 3 May 1934. During the course of his trial Barry excoriated several individuals, including the Bishop of Galway, whose statement made earlier that day, that ‘the IRA were a lot of gangsters and that the arms in these men’s hands were not used for any high national purpose but for intimidation, private revenge and armed robbery’ drew considerable admonishment from Barry.

He also took aim at Broy’s Harriers, whom he accused of assaulting and threatening Republicans. ‘Take this message from me to Deputy Commissioner Coogan that I know of his anxiety to arrest me for the past six months’, Barry stated during questioning, much to the embarrassment of Coogan. Barry was found guilty of possession of a Thompson machine gun and 384 rounds of .45 revolver ammunition, and of contempt of court, by the Military Tribunal. He was found not guilty on counts of having the arms and ammunition with intent to endanger life. He was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment, three not to be enforced if he enters into recognisances in the sum of £10 to keep the peace for twelve months.

Just days after Barry’s sentencing the Irish Independent reported considerable tension prevailed in Limerick City as crowds of Republicans assembled outside a Fine Gael dance held at the Lyric Ballroom on Glenworth St. The paper recounted how the ‘crowds indulged in cheering and party cries, such as “Up, Dev, and ‘Up, Tom Barry’, and uncomplimentary references to General O’Duffy.’ The murder of Hugh O’Reilly went unsolved.

Barry was released at Christmas 1934 but was arrested again the following April and sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment for sedition, unlawful association, and contempt. Barry’s comments during his trial deeply perturbed Deputy Commissioner Coogan, who suspected a leak in his department. ‘It is evident that Mr. Barry has been informed that the investigation was directed by me’, and ‘I regard the leakage of information, coloured to suit the occasion, as a serious breach of confidence which I submit should be investigated by the Minister’, he wrote to the Department of Justice .

His complaint was dismissed out of hand by Commissioner Broy who could not understand Coogan’s call to have an investigation of his own branch. ‘It is incomprehensible to me why a police officer of high rank and well known to have been in charge of Crime Branch for years past should exhibit such signs of perturbation over the remarks of an excitable prisoner in the dock’, Commissioner Broy wrote to the Justice Secretary.

He continued, ‘The best proof that there was no leakage was the fact that such a successful raid was carried out on Barry’s residence, resulting in a long sentence by the Military Tribunal’, Broy continued before adding a deliciously deadly caveat, ‘It is not easy to repose confidence in this officer…and the incident merely hastens a reorganisation of our Headquarters Branches that I have in mind for some time’. Coogan was dismissed from his post in 1936.

Further reading:

Meda Ryan, Tom Barry: IRA freedom fighter (Cork, 2012)

Bowyer Bell, The secret army: the IRA 1916-1979 (Dublin, 1990)

IRA [Irish Republican Army] activities: Attorney General versus Thomas Barry, possession of Thompson machine gun, National Archives of Ireland, Department of Justice files, D/JUS/2011/25/220

Deputy Commissioner Coogan: statement made at military tribunal by Thomas Barry; reports, 1934, National Archives of Ireland, Department of Justice files, D/JUS/ 2006/132/123