The Greater War: Ireland and eastern Europe 1914-1922

John Dorney tries to fit Ireland’s experience of war and nationalist revolution into a wider European context.

The First World War is conventionally said to run from August 1914 until November 1918. The narrative dominant in western Europe is one where peace was shattered by the fallout from the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in July 1914, culminating in the German invasion of Belgium in August of that year but restored when war ended with the surrender of Germany in November 1918.

The western European powers were damaged by the war and incurred millions of casualties. Debates raged over whose fault the war had been and how it was fought, but there was at least consensus that the war was over and that it had been won. Certainly in Britain, the centenary of 1918 will be commemorated as a national triumph and the return of peace.

Ireland’s experience looks anomalous in this regard. There the end of the war saw, not triumphant national unity but state disintegration, as separatists first won an election in 1918 and proceeded to wage guerrilla warfare against British rule. By 1922 Ireland was partitioned and most of it substantially independent. Political violence did not peter out until after the end of the Irish Civil War in mid 1923. There has been, as a result, no consensus in Ireland over what Irish participation in the Great War should mean in hindsight and some bemoan Ireland’s ‘amnesia’ about its participation in the war.

Ireland’s case, where war was followed by nationalist revolution was the norm throughout much of Europe in 1918.

But is Ireland’s case really so unusual? Across a great swathe of Europe warfare did not end in November 1918. The war caused the destruction of no less than four empires – the German, Austro-Hungarian (or Habsburg), Russian and Ottoman- and civil wars raged across their former territories in the years after the Great War over how these lands should be divided and who would rule them.

Greece and the new Turkish Republic fought a bitter war which ended in the mass expulsion of ethnic and religious minorities from both countries. Civil and class war raged in Russia, where the Bolsheviks took power over the ruins of the Tsarist Empire in 1917 and in Hungary, where a ‘Soviet Republic’ was proclaimed but toppled by the right wing military in 1918-19. Finland likewise saw a fratricidal struggle between socialist ‘reds’ and conservative ‘whites’. Germany was also convulsed by intermittent warfare between the extremes of right and left until 1923.

The war caused the destruction of no less than four empires and civil wars raged across their former territories in the years after the Great War

So in most of Europe, the end of the Great War saw not peace but what some historians have called ‘the greater war’. The closest parallels to the Irish experience can be found in those nations that participated in the World War as parts of larger empires only to gain independence in its wake. There too the end of the Great War was followed by several years of violent conflict between rival nationalist projects. And there too the memory of the Great War was obscured by the subsequent fight for national independence.

The closest parallels to the Irish case are Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. We could also cite Ukraine, where the fight for national independence constituted one strand of violence during the maelstrom of the Russian Civil war, or Croatia, which fought in the Austrian Habsburg empire but ended up in 1918 in the new state of Yugoslavia. But in both of those cases no independent state emerged after the First World War.

How close are the parallels between Ireland’s experience of war and revolution in 1914-22 and those in eastern and central Europe?

Ireland and other stateless nations’ experience of war; 1914-18

Ireland participated in the First World War as part of the United Kingdom. Unlike most other European powers, Britain did not have mandatory military service before 1914, so it entered the war with a relatively small volunteer professional army. As a result, facing the mass conscript armies of continental Europe, it had to rapidly expand its land force once it entered the European war in August 1914, which it initially tried to do by voluntary recruitment.

Although Ireland had seemed to be on the brink of civil war in 1914 over whether Home Rule or autonomy would be granted to it, three temporary Irish Divisions (10th 16th and 36th) were raised in this way during the war, with the support of Irish nationalist as well as unionist political parties.

Recruitment in Ireland as a whole was somewhat lower than in the rest of the UK – 6% of the male population in Ireland joined up voluntarily against roughly 20-25% in England Scotland and Wales [1]. Nevertheless it still represented the largest military mobilisation in Irish history. Ireland provided some 210,000 soldiers and sailors for the British war effort (some 58,000 regulars and reservists and about 140,000 volunteers) [2].

What was exceptional about Ireland’s experience is that conscription to the British forces was never imposed.

Devastating battlefield losses forced Britain to introduce conscription by early 1916 but Ireland was, for a time exempted from mandatory military service. John Redmond, Irish constitutional nationalist leader and supporter of the war effort, told the British cabinet that enforcing it in Ireland, in the face of the rising challenge of radical nationalist would be ‘impractical, unworkable and impossible’[3].

Redmond proved to be right. There was little appetite for total war in nationalist Ireland and even less after the suppression of the separatist insurrection in Dublin at Easter 1916. Efforts to actually apply conscription to Ireland in the spring of 1918 proved a disaster for British rule in Ireland.

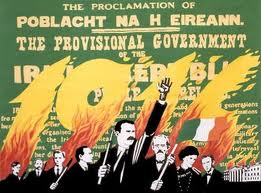

When the British were staring possible defeat in the face with the German Spring offensive of 1918 on the western front, conscription in Ireland was passed into law in March 1918. But the prospect of mandatory military service in an increasingly unpopular war gave birth to a widespread campaign of popular resistance. This included a one day general strike called by the Irish Trade Union Congress and was led politically by the separatist party Sinn Fein. Their victory in defeating conscription paved the way for the party’s victory in the 1918 general election, after which they unilaterally declared Irish independence.

Resistance to conscription was the real moment when most Irish nationalists rejected Britsih rule outright

So while Irish republicans remember the armed insurrection in Dublin at Easter 1916 as being the watershed for the ‘awakening’ of the Irish nation, in a real sense it was resistance to the demands of the British war effort that converted the hitherto passive majority to support for Irish independence.

The war divided Irish people. The families of serving soldiers repeatedly rioted in the streets with republican activists and indeed the armistice of November 1918 saw vicious street brawling in Dublin and elsewhere that left a number of people dead (see here). However by 1918 the full-bodied support of Irish nationalists for the war, promised by John Redmond in 1914 was dead. By 1918 the state’s legitimacy was compromised by its repression of separatist activists and weakened by its failure to impose conscription.

How does Ireland’s experience compare to other stateless nations during the Great War? Like Ireland, nationalist political movements had been rising in east and central Europe in the years before the war.

Poland had been partitioned multiple times since the late 18th century by the rival powers of Prussia (since 1871 Germany), Austria-Hungary and Russia. In 1914 it was partitioned in three. In German-ruled Poland, laws were passed against education in the Polish language and efforts made to restrict Polish land-ownership in favour of German settlers. Similar condition prevailed in Russian-occupied Poland, where the Russian was the only approved language for education and where political dissidents were often exiled and sometimes killed –particularly in the repression of the 1905 revolution.[4]

The case of the small Baltic nationalities of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia was similar, as they were also subject to Tsarist ‘Russification’ policies.

Habsburg administered Poland, widely referred to as Galicia, was by general consensus the most mildly occupied zone.

The Czech and Slovak lands, which after 1918 would become Czechoslovakia, also part of the Habsburg empire, were similarly relatively well-treated, with the Czech language for instance being placed on an equal footing with German in the Empire in 1882. However, here too desire for self-determination preceded the war with, as in Ireland, a ‘cultural revival’ movement rejuvenating nationalist movements.

In Poland, the Czech and Slovak lands and the Baltics, conscription was imposed from the start and wartime losses were much higher than in Ireland

Like Ireland, all of these territories had advanced nationalist movements before 1914. Interestingly also, in the years when Irish nationalist and unionists were forming rival Volunteer militias either to resist or support Home Rule, nationalists in eastern Europe were doing likewise. In Poland for instance, Joseph Pilsudski, a nationalist revolutionary fleeing from the repression of the 1905 revolution in the Russian Empire founded ‘Polish Legions’ in Austrian-ruled Galicia.[5] The Austrians also, incidentally supported ‘Ukrainian Riflemen’ paramilitary group also a proxy against Russian, in 1914. The romanticisation of militarism and patriotism was mainstream not only in Ireland but in all of European culture at the time.

A comparison of Ireland’s war with other stateless nations experience in Europe reveals a much harsher experience of war in eastern Europe than in Ireland.

While Ireland was ultimately spared conscription this was not true for any of the other ‘small nations’ who participated in the war. Poles were conscripted into all three occupying armies – German, Austrian and Russian, as were Czechs and Slovaks into the Habsburg armies and Balts into the Russian ones. As a result, the participation of adult males in the war was much higher than in Ireland. For instance; in Poland alone between 2 and 4 million men were drafted into rival imperial armies and there were similarly huge mobilisations in other stateless nations.

On top of that Poland in particular and also the Baltic territories also became battle grounds, a fate that Ireland (the brief conflagration of Easter 1916 excepted) was spared. For all of these reasons, the toll of war fell much more heavily on these countries than it did on Ireland.

While accurate figures are hard to pin down, a minimum of 27,000 Irish soldiers (listed as born in Ireland in British records) and a maximum of perhaps 60,000 (according to some emerging local studies) were killed in the war.

By contrast in Poland some 450,000 soldiers died and just under a million were wounded.[6] While in what became Czechoslovakia the death toll included at least 180,000 soldiers[7]. In the tiny new Baltic republics of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia the numbers who had died in the war were absolutely smaller but relatively greater than Ireland. Some 64,000 men were drafted in Lithuania and 100,000 in Estonia with respectively 11 and 10,000 killed in action, with another 130,000 drafted in Latvia.[8]

There was also a much higher toll on civilians in the eastern and central European countries. Poland and the Baltic countries were traversed by contesting armies repeatedly who often took supplies by force and in several cases (principally Russian troops) targeted ethnic minorities such as Jews for massacre[9].

The Irish civilian death toll from the Great War is perhaps larger than is sometimes appreciated; apart from around about 250 civilians killed in the Easter Rising, several hundred Irish civilians died aboard the Lusitania a passenger ship sunk by German u-boats off the southern Irish coast in 1915 and another 580 aboard the RMS Leinster off Dublin in October 1918[10]. If we were to count as war related deaths the victims of the ‘Spanish Flu’ in 1918-19 (almost certainly brought back to Ireland by returning troops) then we can add another 20,000 victims at least. But again these figures are dwarfed by events elsewhere in Europe. At least 200,000 civilians lost their lives in Polish territories during the war and some 30,000 starved to death in the Czech lands.[11]

As in Ireland, the Great War compromised the legitimacy of the Empires of eastern and central Europe. Why, nationalists asked, should their people go hungry and their young men die in hundreds of thousands to prop up foreign domination of their country?

Polish and Czech prisoners of war defected to the Allies in very large numbers whereas German attempts to do likewise with Irish prisoners were a failure.

Resistance to participation in British war effort in Ireland was largely confined to the home front, but among the stateless countries of eastern Europe it was very largely a feature of military prisoners of war. This was an unintended result, perhaps, of the conscription of so many minority nationalists into Imperial armies in those countries. In Poland a nationalist ‘Blue Army’ was recruited by France from Polish prisoners of war from the German forces. It served in French service on the western front with the aim of returning to liberate Poland. In Poland itself the Germans attempted to use Pilsudski’s exiled ‘Polish legion’ against the Russians, but were in the end unable to ensure their acquiescence and had Pilsudski himself arrested. Another Polish Legion was recruited by the Russians.[12]

Similarly the Russians recruited the ‘Czechoslovak Legion’ from Czechs and Slovaks captured while fighting in the Habsburg Austro-Hungarian armies. The Legion would go on to represent patriotic resistance and heroism in independent Czechoslovakia.

One peculiarity of the Irish experience in this context is the complete failure of the Germans’ ‘Irish Brigade’ organised by Roger Casement, to attract more than a handful of Irish prisoners of war to join up – they got in fact only 56 recruits out of thousands of Irish prisoners of war[13].

The wars after the War

Did the industrial mass killing set off in 1914 lead to the outbreak of mass paramilitary violence in its aftermath, in Ireland and elsewhere?

Defeat in war shattered the existing states from the Rhine to Siberia in 1918. Into this vacuum of authority rushed a host of competing political movements, most of them nationalist (some extreme nationalist or fascist) some communist or socialist. Everywhere war veterans were prominent in such movements, though historians have also noted that young men who ‘missed’ the Great War often wanted to compensate by increased paramilitary zeal in its aftermath.

Throw in also the proliferation of weapons and trained military personnel and civil and inter-state violence became almost a certainty as rival groups fought for sovereignty. Without the state destruction and collapse caused by the Great War there would not have been a series of civil wars across eastern and central Europe in 1918-23.

In Ireland as elsewhere the mass bloodshed of 1914-18 made the use of political violence at home more palatable.

Ireland fits in a little awkwardly here. The British state may have been discredited but it had not collapsed in Ireland in 1918, far from it, it was in fact present in the form of a larger military garrison and more repressive legislation (the Defence of the Realm Act or DORA) than ever before. But in Ireland too the war introduced mass killing into the lives of tens of millions of Europeans and made the prospect of civil bloodshed seem less unthinkable than it may have been before the war.

So thought James Stephens, a writer who observed the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916 and wrote;

In the last two years of world war our ideas on death have undergone a change. It is now not a furtive thing that crawled into your bed and which you fought with pill-boxes and medicine bottles. It has become again a rider of the wind with whom you may go coursing through the fields and open places. All morbidity is gone, and the sickness and what remains to Death is now health and excitement. So Dublin laughed at the noise of its own bombardment and made no moan about its dead.[14]

When soldiers did come home to situations of political violence, they took with them the skills and often the weapons they had taken from the fronts. In Ireland the most famous example is the British deployment of war veterans in the paramilitary police forces the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries and local unionist veterans in the Ulster Special Constabulary. By and large the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was suspicious of Irish ex- soldiers who had served in the British forces.

But ex-soldiers could also be found in republican units. While some accounts have depicted Irish ex-servicemen only as IRA victims (about 80 were killed as alleged British informers), a total of 16 ex soldiers died in the ranks of the IRA during the War of Independence (out of a total of some 500 IRA fatalities) [15]. War veterans such as Tom Barry and Emmet Dalton made it into the highest ranks of the organisation based on their military training. In the Civil War period the role of ex-soldiers was even more prominent, especially on the Free State side, with perhaps half of the National Army of 1922-23 made up of ex-soldiers.

War veterans played a key role in nationalist fighting forces elsewhere but in Ireland were a more marginal force in republican units.

Everywhere war veterans, now fighting as paramilitaries, helped to re-shape Europe. Poland emerged from ruins of three empires in 1918 and declared a new Polish Republic in 1918. It was very largely the return of Polish veterans from the various armies of Europe (Russian, German, Austrian and French) that helped to make the reborn Poland a reality. While in theory they were re-constituted as a national army in October 1918, up to March 1920 the reality was of a conglomerate of paramilitary Polish volunteer units.[16]

However the borders of Poland, suppressed for over 100 years, were far from clear. Should they, as some nationalists such as Pilsudski’s socialists wanted, extend over the territory of the old Commonwealth of Poland (dissolved in 1795) and take in millions of ethnic Ukrainians and Jews? Or should it, as other, more right wing elements such as the National Democrats preferred, be concentrated on a compact ethnically Polish core? Questions of partition along ethnic or communal lines, as occurred in Ireland in 1920-22, was therefore by no means confined to this country in post-war Europe.

Both to fight off attempts to strangle its newfound independence but also to expand it borders at the expense of its new neighbours, Poland fought no less than nine separate wars between 1918 and 1922. A ‘Greater Poland Uprising’ in 1918-19 expelled the remaining German troops and paramilitaries from central Poland and three more ‘national insurrections’ in Upper Silesia led eventually to the partition of that province between Germany and Poland. An attempt by Bolshevik Russia to annex Poland was fought off in 1920 after a desperate last stand near Warsaw.

Some of these wars such as the struggle with Germany and with the nascent Soviet Union have gone down in Polish legend as icons of national resistance but others were less edifying. Wars were also fought to seize territory off Lithuania and Czechoslovakia and as a result of land taken after the defeat of the Red Army, much of eastern Poland was populated by ethnic Ukrainians. [17]

Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania meanwhile, although they had been part of the Tsarist Empire, found themselves in 1918 still occupied by German troops. While the Imperial German Army dissolved in late 1918, right wing German paramilitaries such as the Landeswehr and the Freikorps fought against the Baltic nationalists (and also at time Bolshevik forces) in an attempt to annex these territories (then with a significant German minority) to Germany. Some 200,000 returning Baltic war veterans organised in nationalist paramilitary units eventually forced German forces out of the Baltics in late 1919. The Lithuanians also fought and lost a border war with the Poles. [18]

The Czech Legion in Russia meanwhile, played a confusing but important role in the Russian Civil War and helped to ensure the Allied Powers recognition of the independence of Czechoslovakia. Even in relatively peaceful Czechoslovakia however there were border conflicts with Poland and Hungary.

The ‘greater war’ in Ireland : As bloody as the others?

Political violence in Ireland from 1918-23 was in general more restrained and less bloody than irregular wars elsewhere.

Like the conventional war of 1914-1918, Ireland’s experience of internal irregular was in 1918-23 was, on the whole, less extreme than elsewhere. In Ireland roughly 4-5,000 people died, whereas elsewhere the death toll was fearfully higher (over 100,000 died in the Polish-Soviet War alone for instance). Moreover, violence elsewhere tended to be much more indiscriminate than in Ireland. While the IRA’s shooting of some 200 civilian informers continues to cause regret in Ireland today, and British forces killing of perhaps 4-500 Irish civilians still causes great anger, the figures pale into insignificance compared to the fearful atrocities committed against civilians elsewhere in Europe in the wake of the Great War.

The German Freikorps particularly, composed of right wing former soldiers in the main, committed mass slaughter against both left wing class enemies at home and rival nationalists in eastern Europe. In crushing a general strike and left-wing insurrection in Berlin and Munich in 1919 for instance, they killed some 2,000 unarmed or disarmed people, many of them prisoners. While in Latvia in the same month, Freikorps units were accused of massacring as many as 3,000 civilians after their seizure of Riga. [19] Were we to venture further east, the Bolsheviks’ ‘Red Terror claimed tens of thousands of unarmed victims during that civil war.

Moreover at least one historian has made the point that violence in eastern Europe compared to Ireland was often far more brutal in character as well as in body count. T.K Wilson in a comparative survey of ‘ethnic’ or communal violence in Ulster and Upper Silesia (disputed territory between Poland and Germany) found that ‘transgressive violence’ – extreme violence such as rape, torture and mutilation was far more common in Silesia than in the north of Ireland. [20]

Wilson argues that in Ulster the role played by religion in communal barriers controlled violence , as barriers between communities were more rigid than linguistic ones in Silesia. This meant that retaliation in kind was certain for atrocities, which discouraged them.

Whether or not we accept this argument, in a wider sense, it is probably true to say that the fact that state breakdown did not occur in Ireland at any point, that armed forces were for the most part curtailed in their excesses by civilian government ameliorated violence. At no point in Ireland did guerrilla war become a war of extermination between rival ethnic or ideological groups as it did elsewhere.

Memory

In many ways Ireland’s experience of the First World War and its aftermath has more in common with eastern Europe than with the rest of western Europe. Like Poland and Czechoslovakia, the three Baltic states and elsewhere, Ireland participated in the Great War as part of a bigger empire and got its independence directly after the conflict, after a great deal of internal upheaval and death.

Like those countries, post-independence politics were dominated by nationalism in Ireland. A large part of this was the result of a rejection of the formerly existing empire and their part in the First World War. Ireland’s ‘forgetting’ of the First World War has often recently been painted as an extreme ‘air-brushing of history’.

However, looked at in the light of eastern and central Europe Ireland’s experience is not extreme at all. In Ireland there was no ban on commemorations of the war, in fact the Free State devoted a large grant to constructing the memorial gardens at Islandbridge in Dublin. Remembrance Day demonstrations were sometimes harassed but republicans but never by state security forces.

Contrary to what is often said today, Ireland’s ‘amnesia’ about the First World War is not at all unusual in the context of other nation states that emerged from the war’s aftermath

By contrast in Poland, where over 450,000 men died in the war in the armies of Austria-Hungary, Germany and Russia, there has never been a single memorial to their memory, only to the Polish nationalist soldiers who deserted to fight in Allied ‘Legions’ or who fought Poland’s various enemies for independence after the war. The same is largely true in the Baltic countries.

In Russia itself, where over 2 million soldiers died in the First World War, because of the Bolshevik revolution, which disavowed the ‘imperialist war’, the Soviet Union did not erect a single memorial to the 1914-18 war either. Plenty however were erected to Red Army fighters in the subsequent civil war. (Vladimir Putin, as part of his drive to rejuvenate Russian nationalism has made some noises recently about changing this).

The closest experience to Ireland’s seems to have been Czechoslovakia, where there are memorials to those who died in the Habsburg armies, but Czechs preferred to remember the Czech Legion, who emerged from Czech prisoners of war to fight for independence. A recent television programme argued, “whilst members of the Czech Legion enjoyed fame and glory in the first days of Czechoslovakia, men loyal to the Habsburg monarchy fell silent”.

The rejection of the war was not at all unusual in the new states of interwar Europe. And people in all countries choose to remember most the history which is most useful to their sense of national identity.

References

[1] Keith Jeffrey, An Irish Empire? Aspects of Ireland and the British Empire, p98

[2] David Fitzpatrick, Militarism in Ireland 1900-1922, in Thomas Bartlet, Keith Jeffrey, ed. A Military History of Ireland, p386

[3] Joseph P Finnan, John Redmond and Irish Unity, 1912-1918, p110

[4] See Adam Zayoski, Poland a History, pp270-275

[5] Zayoski, p288-289

[6] Zayoski p289

[7] Clodfelter, Michael (2002). Warfare and Armed Conflicts- A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–2000 2nd Ed.. ISBN 978-0-7864-1204-4. Page 479

[8] Tomas Balkelis, Baltic Paramilitary Movements after the Great War in Robert Gerwatrh, John Horne eds. War in Peace, paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War, p129

[9] Niall Ferguson The War of the Worlds, p 136-138

[10] Padraig Yeates, A City in Wartime, Dublin 1914-1918, p254

[11] Clodfelter, Michael (2002). Warfare and Armed Conflicts- A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–2000 2nd Ed.. ISBN 978-0-7864-1204-4. Page 479

[12] Zayoski p290-91

[13] A list is here http://www.irishbrigade.eu/recruits-irish-brigade.html

[14] James Stephens The Insurrection in Dublin, p37

[15] Eunan O’Halpn, Counting Terror, in David Fitzpatrick ed. Terror in Ireland, p154

[16] Julia Eichenberg, Poland and Ireland after the First World War, in War in Peace, p188

[17] Zayoski p290-296

[18] Balkelis Baltic Paramilitary Movements, War in Peace p129

[19] Annanarie Samartino, The Impossible Border, Germany and the East 1914-1920

[20] TK Wilson Frontiers of Violence,Conflict and Identity in Ulster and Upper Silesia, 1918-1922, pp212-217