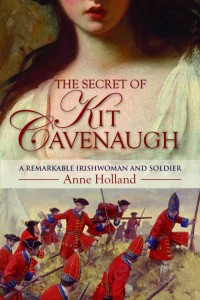

Book Review: The Secret of Kit Cavenaugh: A Remarkable Irish Woman and Soldier

Book Review: The Secret of Kit Cavenaugh: A Remarkable Irish Woman and Soldier

Book Review: The Secret of Kit Cavenaugh: A Remarkable Irish Woman and Soldier

by Anne Holland

Published by Colilns Press

Reviewer: Lucy Kinnally

When author, Anne Holland stumbled across a small item in the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards museum in Edinburgh Castle referring to ‘Mother Ross’ she was instantly intrigued. Mother Ross, better known as Kit Cavenaugh, a seventeenth century woman who disguised herself as a man and enlisted in the British Army to find her press-ganged husband, was the type of historical figure that writers dream about.

Kit Cavenaugh, disguised herself as a man and enlisted in the British Army in the early 18th century to find her press-ganged husband.

She survived numerous battles and managed to keep her sex a secret despite sustaining three injuries and continued to serve the British Army in various capacities for over fifteen years. Hers was a story that was begging to be told. Unfortunately, Holland’s book, The Secret of Kit Cavenaugh: A Remarkable Irish Woman and Soldier, in its creative nonfiction style, manages to take what could be a compelling story of love, adventure and unbridled bravery, and turn it into a plodding narrative of conjecture and what ifs.

According to The Secret of Kit Cavenaugh, Christian ‘Kit’ Cavanaugh was born in 1667 in the outskirts of Dublin to a middle class Protestant farming family. Despite being Protestant, Kit’s father supported King James II and served in the Jacobite Army, where he died in the Battle of Aughrim. After his death, his lands were seized by the Williamite government and Kit and her family were left destitute.

To escape poverty and a cousin who took advantage of her, Kit moved to Dublin to help her aunt run a pub, which she eventually inherited upon her aunt’s death. It was here, in her aunt’s pub, that Kit met her husband, Richard Welsh, who would change Kit’s life and set her onto the adventure that would make her infamous.

Kit and her husband, Richard, lived a very happy life until Richard disappeared one night, leaving Kit behind with two children. After several months of wondering what had become of her beloved husband, Kit received a letter from him, explaining that he had been forced into the Army and shipped across the sea. Hoping to find her husband, Kit enlisted in the British Army as Christopher Welch and began a life that saw her serving in the War of Spanish Succession, being detained as a prisoner of war in France, courting a Burgher’s daughter, fighting duels, and even being accused of fathering a child.

Kit enlisted as Christopher Welch and fought in the War of Spanish Succession, was taken prisoner in France, fought duels, and was even accused of fathering a child.

Eventually, beyond all odds, Kit managed to find her husband who had been living with a Dutch woman. Unwilling to give up her life as a soldier, Kit convinced Richard that they should both remain in the army, which they did until her sex was finally discovered when a stray shell fractured her skull. Though discharged from the army, kit decided to follow Richard’s regiment, becoming a cook and a sutler, associating with the British army for many more years.

Kit’s life as a soldier and sutler was so extraordinary that she was eventually presented to Queen Anne and granted a shilling a day as a pension for her service, but her years of adventure made ordinary life difficult for her and she had a hard time adapting to normal life.

Holland does an excellent job of explaining the minutia of the eighteenth century life of a soldier but the ‘creative non-fiction’ approach does not work.

Kit Cavenaugh’s life truly was an extraordinary one and it is one that should have made a superb book. Holland does an excellent job of explaining the minutia of the eighteenth century life of a soldier and manages to construct a fairly complete narrative of Kit’s life from the limited sources that are available, relying heavily on, The Life and Adventures of Mrs. Christian Davies, Commonly Call’d Mother Ross, a book published a year after Kit’s death in 1740, purportedly written by Kit herself, to do so.

But the lack of biographical information led Holland to take the rather unusual strategy of writing in a creative nonfiction style, attempting to merge facts with dialogue and filling in space with speculation of what Kit might have been thinking, wearing, feeling or doing. Phrases such as, “perhaps she,” “she may have” or “Kit probably . . .” crop up repeatedly, placing thoughts and experiences into Kit’s life that are complete speculation.

This not quite fact, not quite fiction, style of writing is slightly frustrating as Holland could have been successful in writing a very interesting and insightful, though shorter, biography of Kit, or a truly gripping novel. In the end, Holland’s book ends up like Kit herself, hovering between two worlds and not really fitting into either, disguising itself in the garb of nonfiction, while harboring fictitious tendencies. But perhaps, like we do with Kit, we should just applaud Holland for being brave enough to do so.