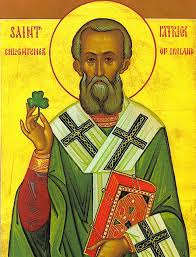

Saint Patrick – Man or Myth?

By Brighid O’Sullivan

By Brighid O’Sullivan

The man known as Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland is shrouded in so many fantastical stories that one wonders if he was a man at all. The real Patrick was a simple human being who was kind, gentle, courageous, and confident in his beliefs. True, he was larger than life but not the way most people think.

A Roman nobleman

Maewyn Succat is the name given at birth to the man we know as Patrick of Ireland around the end of the 4th century. Most likely, he was born in Britain and the son of a Roman deacon named Calpornius who was also a tax collector. His grandfather was Potius during the reign of Constantine the Great, first Christian emperor of the Romans so it is easy to see how Patrick would be influenced in ‘the family business’ from an early age on. As one of Roman nobility, a station of honor and privilege, Patrick would have had hereditary privileges as well. His father would have had high hopes for his son, knowing he could one day rule over his less fortunate countrymen.

As one of Roman nobility in Britain, a station of honor and privilege, Patrick would have had hereditary privileges.

There is no clear answer to where Patrick lived although he does give us several hints through his writing. He talks about his family estate near a town called Bannaventa Berniae and although the location of this town is unknown, it is likely that wherever he lived, it must have been close to a seaport to enable his easy capture by Irish pirates.

This is why the explanation of a town called Bannaventa is less likely and thought to be a miscopied for it is seventy miles from the nearest port. If he lived in Glannoventa, it would make more sense. Glannoventa was close to the western coastline and would have afforded the Irish a bandits a speedy escape.

At the age of sixteen, Patrick’s abduction from Roman occupied Britain by Irish raiders landed him in Ireland as a slave.

Slavery

Slavery in Ireland was much like Roman Britain except for one thing. Though probably rare, a Roman slave could change his lot in life by buying his own freedom. In pre-Christian Ireland, slaves could not buy their freedom or be set free. Irish law forbid it, believing it would upset the natural order of life. Since Ireland was a pastoral society, it was thought that to upset the natural world, would lead to crop failures or barren livestock.

So what was Patrick to do? If he yearned for a better life, he needed to escape. After six years of tending sheep, that is exactly what he did.

Patrick did not introduce Christianity to Ireland but he did bring it into line with mainstream Christian practice.

Neither Patrick nor Ireland was new to Christianity but Irish Christians were not the same as the rest of Western Europe. Irish Christianity had survived by blending slowly with Paganism although, no doubt Christianity appeared odd to the native Irish.

The difference was Patrick grew up under the Roman influence. For instance, he began fasting. This would have impressed a bizarre idea to those of Ireland. Under Irish Brehon law, fasting shamed a person; it was not a form of prayer. If someone committed a crime, a man received justice by ‘camping out’ on the defendant’s steps, right outside his door, neglecting to eat or drink until his oppressor paid him an ‘honor price.’

Patrick stated that God appeared to him and told him simply to go home, whereupon he escaped from captivity.

Living as a slave tending sheep near the Western Sea, Patrick must have thought of nothing but escape. Life for a slave was harsh and exhausting. Especially for a boy who grew up privileged.

After six years of this, he says that God spoke to him in a dream, telling him to go home and even where to get the boat. These dreams must have given him great courage for not only would he be a fugitive, punishable by death if he were caught, but Ireland was a difficult terrain with few roads, treacherous bogs, numerous hills and streams and no family to shelter him along the way.

There may have been a law about hospitality and now and again bruideans, which were like bed and breakfasts but for the most part it was dangerous to venture outside of a clan’s territory. So where was the boat? Ships would naturally only come into trading ports. Archaeological evidence points to areas around Dublin Bay, the Boyne Valley, or present day Belfast. Patrick would have had to offer his services as a sailor unless he had something to bargain with. That part we will never know.

There is something surprising in Patrick’s letters about his encounter with the sailors who took him on board. Something so strange medieval scribes have tried to change it. Patrick writes that the sailors of the ship asked him to “suck their breasts” as a token of acceptance which he flatly refuses. The ritual may not be as unusual as it seems, referred to by an old text between the Irish King, Fergus mac Léti and a dwarf, as well as in Algerian folk tales told in modern Africa.

Salvation

So what happened after Patrick escaped? He states that he and the crew plus a pack of dogs ‘wandered for twenty-eight days through empty country’ leading us to believe that the ship landed somewhere off course. It is possible they were caught in a storm, landing them in Wales or Cornwall for he describes the land as deserted and Britain would have been heavily populated at the time.

After 2 weeks, the desperate captain demanded Patrick pray to his God for food because they were close to starving. Patrick responds with confidence and prays. Soon, a large herd of pigs appears and later they find some wild honey, which Patrick refuses when he learns that the honey is a sacrifice to Pagan Gods.

Instead of becoming a tax collector like his father, Patrick trained as a cleric and returned to Ireland

Once home at last, Patrick’s father would have encouraged 22 year old Patrick in his Christian training, perhaps not realizing what Patrick’s goals were different from his own. Following in Calpornius’ footsteps would have meant politics and tax collecting but Patrick had other ideas. He planned to go back to Ireland but first he had to complete his religious education.

The place where he trained may have been Lérins, a monastery on an island off the Tyrrhenian Sea. Some people think he trained in Gaul, others that he stayed in Britain but wherever Patrick trained his family ties and influence would have held some sway in getting him admitted as his early years of training were missing and his Latin was sketchy at best. We are not sure if Patrick was bishop or a deacon when he returned to Ireland but he was not the first Christian, perhaps not the first bishop either though certainly one of the most loved.

Converting the Irish

So how it was that Patrick was so successful in converting the Irish when others before him could not? What were his challenges? For one, he was a very simple man, compassionate and understanding of the Irish. Instead of working against them, he worked within their systems much as possible and made many friends along the way. Still, Ireland was a very dangerous place and people were spread out, not in close proximity, as there were no towns like in other parts of Europe.

Patrick was compassionate and understanding of the Irish. Instead of working against them, he worked within their systems much as possible and made many friends along the way.

Tribal borders were strictly enforced and Patrick suffered many narrow escapes with his life, which he attributes to God’s interventions. He soon realized that travel in this harsh land required careful planning and it was necessary to pay bribes to tribal kings for safe passage through their territories. Often, the king’s sons became his bodyguards and kept him safe.

So who were Patrick’s converts? A good majority of them were women. Patrick states: the number of virgins who have chosen this new life continues to grow so that I cannot keep track of them all. He was right. In choosing Christianity, women chose virginity. Both slaves, widows, married and single women alike would have seen a great advantage in becoming celibate or remaining virgins.

Women would have few choices. In following Patrick’s teachings, they could have escaped constant childbirth, which had obvious risks and possibly the control of their husbands and brothers. Slaves faced the threat of constant rape, widows being married off by male relations and parents needed their children to cemented alliances with rival tribes. Some of the women offered gifts to Patrick, often leaving jewelry on an altar but Patrick returned what they offered him. He also explains that when asked to leave Ireland he was loath to abandon his female followers.

Many of Patrick’s converts to Christianity were women. Some of his followers were killed and sold as slaves.

Not all of Patrick’s missions, no matter how carefully planned, ended in glory.

Close to Easter Sunday, a terrible thing happened. Patrick had just baptized a group of his followers on a beautiful spring day when they were attacked on their way home, still dressed in their baptismal robes with sweet oil on their heads. The men were all killed; women and children kidnapped to sell at slave markets in Britain, brutally ripped from their native land much as Patrick was as a young boy. Patrick was both devastated and furious. His beloved Irish, many he would have called friends were slaughtered like cattle. He knew who was responsible, a brutal warlord named Coroticus.

His letter to the Coroticus drips with anger and indignation. He calls his fellow Romans citizens of Hell and insists on the captive’s release while imploring fellow Christians in Britain to shun Coroticus and his soldiers. Do not have anything to do with them. Don’t eat, drink or accept charity from them but cry to God to free these Christian women and captives. We can hear Patrick’s desperation and sorrow in his letter. He assails Coroticus with endless scripture and describes the warlord’s actions as selling his fellow Christians to a brothel.

Patrick called on Roman Britons to boycott Irish chieftains who had enslaved Christians. Surprisingly this infuriated the Church.

The church’s response to this letter? It infuriated the British church. How dare a bishop of Ireland take matters into his own hands? Patrick should have contacted the British bishop to discipline Coroticus. So why didn’t Patrick do this? Several reasons. It was unlikely a British bishop would have chastised a man of Coroticus position when it did not involve British citizens.

In addition, to take actions against Coroticus, may have had consequences to the church. Patrick knew it would take time to go through the proper channels as well, and he was hoping to affect the release of the captives. He simply could not wait but like all politics, including those of the church, there were consequences to Patrick’s actions.

Relations with mother Church

Patrick was not a favorite of the church. He spoke Irish better than Latin, had less training, less discipline and cared more about the Pagan Irish than listening to his superiors. His statements of giving back gifts would have enraged a greedy church. He should have kept the gifts or sent them abroad to fund church expenses. Patrick himself admits that he used church funds to bribe the Irish kings so that he could move freely throughout the island. The British bishop and clergy accused Patrick of hoarding Irish riches and keeping it for himself. As his ministry grew, they saw promises of church riches, unexplored, unclaimed by the church.

Patrick always had a fractious relationship with his superiors.

They insisted he act responsibly toward the church. But what to do about Patrick? He was summoned back to Britain to face his charges. Patrick knew that if he left Ireland, he would never come back. He’d worked so long with his followers, had become loved and accepted and to leave would have meant the possible collapse of all he’d worked toward. He was not about to go down without a fight.

In a letter known as his Confession Patrick not only defends himself against charges of corruption, but also admits how imperfect he is and that he knows he is despised. He talks about his lack of literary skill and that he is ashamed and awkward, apologizes while explaining his story in simple words. The confession appears to be his will. He is asking to die in Ireland and is writing when he is an old man.

He talks about revelations from God, is forced to admit that he did something terrible as a youth. This sin in his youth was betrayed to the church by a trusted friend. Perhaps it was the icing on the cake, their last straw with this wayward bishop.

How ironic that we now have a special day called St. Patrick’s Day, a time filled with celebrations and joy, named after a man who was compassionate and gentle, a day set aside in remembrance of Patrick’s life’s work, an appreciation he never obtained when he was alive.

Brighid O’Sullivan writes about Irish history @ Celticthoughts.com