The Irish Press Slum Crusade 1934-36

Barry Sheppard looks at attempts at slum clearance through the eyes of the Irish Press.

Barry Sheppard looks at attempts at slum clearance through the eyes of the Irish Press.

Throughout the early 20th century, the Irish capital Dublin was a city notorious for its inner city slums. Many hoped that independence from Britain would solve the problem, but by the 1930s Irish governments had still failed to deal with it. In 1936 an Irish Press editorial opined;

In truth, it is not the want of inquiry that can be complained of, rather want of action, of driving power of the determination at any cost to abolish an evil, the existence of which had been so abundantly demonstrated…The Dublin slums remained all the time, as they are today, Ireland’s most pitiable and heart-breaking tragedy.[1]

While urgent calls for action by a politically engaged newspaper are not surprising, the identity of the newspaper was. The Irish Press had been founded as a forum, even a mouthpiece for Eamon de Valera and Fianna Fail.

The paper’s campaign for slum clearance therefore in 1934-36, a time when Fianna Fail was in government, is therefore worthy of close inspection.

The Irish Press

The now defunct Irish Press newspaper (1931-1995) has been described as a revelation in Irish print media. When it launched in September 1931, the publication quickly proved itself to be a ‘brilliant journalistic endeavour’, comparable to William O’Brien’s United Ireland (1882) in its immediate impact. Written with rumbustious flair, it achieved a meteoric rise in circulation within its first two years of publication.[2]

Politically aligned to Fianna Fáil, the paper was credited with being a ‘fine propaganda tool’ for the party on the run-up to the all-important 1932 general election.[3] Indeed, it was credited with helping sway undecided voters towards Fianna Fáil in both the 1932 and 1933 elections.

The Irish Press, founded to give a voice to anti-Treaty republicans, helped to win the 1932 and1933 elections for Fianna Fail

The paper’s close relationship with Fianna Fáil is evident, given that two of the State’s first three Taoisigh (de Valera and Sean Lemass) and three of the first five presidents (de Valera, Erskine Childers and Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh) all held senior positions on the paper.[4]

Under the watchful eye of its first editor, Frank Gallagher (who has been allocated the extreme title of ‘The Irish Dr Goebbels’, for his mastery of Irish Republican propaganda), the paper elevated Fianna Fail, through Gallagher’s direction and the charisma of de Valera to be the guardian of the nation’s Catholic soul.[5]

The first editorial set out the paper’s mission, it was to be “a newspaper technically efficient in all departments, assured of material success, yet seeking above all thing the freedom and well-being of the nation.”[6]

Despite the apparent success in terms of circulation and political influence, prolonged friction between Frank Gallagher and the board saw his resignation in June of 1935, less than four years after the paper’s first edition. His departure proved unpopular among the staff and some of those who sat on the board, especially those who were card-carrying Fianna Fáil members. Fianna Fáil Senator and Irish Press board member Joseph Connolly was particularly despondent about Gallagher’s departure, stating:

Under Frank Gallagher’s editorship the paper established itself as a trustworthy and reliable journal, bright without being cheap, cultured without being ponderous and above all Irish through and through in the things that mattered. It was to me a tragedy not only for the paper but for the country when Gallagher ceased to be editor.[7]

Connolly further stated that in the wake of Gallagher’s departure the tone of the paper gradually deteriorated, with a new undesirable streak creeping in.[8] It should be no surprise that someone with such close ties to the board of the paper and the ruling party lamented the departure of a man credited with harmonising the two. For an alternative take on the situation, Joe Lee suggests that “for a stridently popular paper, it descended to the gutter level remarkably rarely”.[9]

There is no doubt that with Gallagher’s departure the paper was afforded the chance under two of his successors, John O’Sullivan and John Herlihy to distance itself further from Fianna Fáil than it had been under Gallagher.

Arguably, one of the first real opportunities to do this was in late 1936, when the paper began a very public campaign against the continuing problem of slum conditions in Ireland’s large towns and cities. Such an ambitious exposé couldn’t exactly be classed as falling into the ‘gutter’ category, although it may have led to uncomfortable reading for some connected with the ruling party.

This ambitious campaign could easily have been a source of embarrassment to some in Fianna Fáil who had, in part presided over these conditions four years into their role as the governing party of the state.

Slums

Urban dwellers in slum conditions were seen as being forgotten by Fianna Fáil in favour for their rural-centred vision for Ireland, as outlined in the party’s 1926 manifesto. It has certainly been argued that programs of unemployment assistance, relief works, and subsidies for local authority and private housing tended to favour rural households rather than city dwellers.[10]

The slums of Ireland and in particular Dublin had long been a pressing issue, to the point that they have now been granted an almost legendary notorious stature in the nation’s history. Following one of the most infamous incidents involving slum housing, the Church Street tenement collapse in September 1913, increased calls for a remedy to the situation led a housing inquiry to be established by the Local Government Board for Ireland.

Published in 1914, the report found that around thirty percent of Dublin’s population lived in slums in various parts of the city, with three quarters of tenement households living in single rooms.

The inquiry also found that 60,000 people in the city occupied housing which was almost or actually “unfit for human habitation” and needed to be re-housed and that the signs were that the housing problem was getting worse and that even a massive renovation program would not suffice to solve it.[11] This report was one of a number of times attention had been drawn to the appalling conditions people had been forced to exist in.

The Irish Press Crusade

In 1936, in the post-Gallagher era the Irish Press mounted a public crusade to highlight the plight of those still wedged in sub-standard accommodation over a decade into independence. The appointment of Gallagher’s replacement, John O’Sullivan was in itself controversial.

When Gallagher resigned in June 1935 he was consulted by de Valera as to who would succeed him. Gallagher’s choice for editor was either Bill Sweetman, at that point lead writer, or sub-editor Patrick O’Reilly.

In the end, Gallagher suggested Sweetman for the job as he was already moulded to the role. However, this was not to be the end of the matter. The man who eventually was given the job was former Irish Times reporter John O’Sullivan.

Only a day after O’Sullivan’s appointment an article which he had co-written appeared in several regional papers blaming Frank Gallagher for The Irish Press’ perceived close relationship with Fianna Fáil, resolving that the direction of the paper would now be less partisan than it had been up to that point.[12]

The Press campaign for slum clearance, with its implicit criticism of Fianna Fail, can be seen as a departure in its relationship with the party.

The public campaign highlighting urban deprivation in a number of Irish cities and large towns began in late 1936. It can be argued this was a dramatic departure from the previous cosy relationship with Fianna Fáil.

Regardless of whether this campaign brought it into friction with the Government, the paper was in no doubt of where the root of the problem of Ireland’s slum housing was to be found, the legacy of British occupation. Under a headline ‘Demand for an End to Tenement Squalor: Tragic British Legacy’, the paper stated that the slum situation had to be taken in retrospect in order that its extent, its enormity, and its deep-seated nature may be fully appreciated.

This piece was merely a continuation of anti-treaty Sinn Fein editorials from the early 1920s onwards. In An Phoblacht (which Frank Gallagher had previously edited) in 1925, over a decade prior to this campaign Sean Lemass asked: “Who could walk through the slums of Dublin and see the squalor and misery which foreign domination has brought in its train and console himself with this grandiloquent philosophy”?[13]

Noting the previous inquiries into slums, eleven in total, the paper showed that the number of families in dire conditions had not changed significantly over the previous 138 years. In fact, it was pointed out that in many cases they had gotten worse.[14]

While the finger of blame is squarely pointed at the British who were responsible for ten of the eleven inquiries held into Dublin slums, it is of importance that one of them was undertaken under a native Irish administration, Fianna Fáil, with its connections to the Irish Press all too obvious. Therefore, they too shared some blame in this ‘nightmare of shame’.

Religious Leaders

The Press crusade not only cut through party political lines with its ambitious project, it also cut across denominations, and not only ‘traditional’ Irish denominations. As mentioned above, there was a view that Fianna Fáil had been elevated to guardian of the nation’s Catholic soul with the help of the paper.

Now the paper sought to bring on board souls of other faiths. It sought the help of the heads of other churches in the state and received very public backing from leaders of the Protestant denominations, and the Jewish community within Ireland.

According to the paper, the Chief Rabbi of the Free State’s Jewish Community, Dr Isaac Herzog (who was later to be elected as Chief Rabbi of Palestine) was so ‘shocked and mortified’ by the conditions which he saw first-hand, that he waived his usually inflexible principle of never issuing statements to the press on Feast days. Dr Herzog sated:

If the public treasury cannot afford to provide the necessary funds for the abolition of these awful slum conditions in Dublin, then a public appeal should be made to the generosity of the Irish nation. I will go so far as saying that it would be advisable to appeal to the vast body of Irishmen living in America who, I am sure, will contribute generously towards a fund which aims at removing so serious a blot from the capital of Ireland, which is, to all Irishmen, the historic symbol of the Irish spirit and whose historic and national glamour is dimmed in no small measure by these wretched slums.[15]

The appeal to America itself must have been of embarrassment to the ruling party, and to de Valera, who had raised American money on his extensive tour of the country in 1919-1920. This fundraising trip became a political hot potato itself, given that this was in part the source of funding from which the Irish Press was established.

The call for American financial intervention was not echoed by the Rev Dr John Gregg, Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin. Dr Gregg also praised the work of the Irish Press in bringing this public attention. In contextualising what he saw as the gravity of the situation, he compared the work to missionary work in the developing world.

‘I agree with the Irish Press that the problem must be tackled courageously and comprehensively in our time and not left to posterity…It is really missionary work…Missioners go abroad and risk their lives and are often killed for their zeal, as in China. Here is as great a missionary effort at home. It is a religious question embracing all, for we are all brothers and members of the one family of God’.[16]

Other Cities

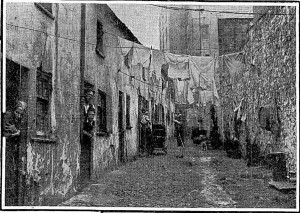

Historically, much of the focus upon sub-standard housing was on Dublin. The Irish Press took the decision to expand upon this to include some of the larger towns and cities around the Free State. Exploring the situation in Limerick, Cork and Waterford, the paper gave much-needed publicity to these locations. On 20 October 1936, the paper launched its ‘National Slum Survey’, which carried the headline ‘Beginning the Story of Ireland’s Other Slums’.

It was claimed that following repeated requests from various sections of the country to the Irish Press to investigate this shame on Ireland’s name it would widen the scope of slum articles to ‘a national aspect’. With Dublin conditions set as the benchmark of the worst of housing, Waterford was described as being ‘as bad as’ the capital with half a million pounds, and 15 years needed to eradicate the menace. It was further claimed that some 1,300 families were in dire need of rehousing, with overcrowding being ‘worse than in Dublin’s most teeming tenements’.[17]

Slums were often seen as Dublin problem, but in fact they existed throughout Ireland.

In Cork, the City Manager Mr Philip Monaghan accompanied an Irish Press ‘investigator’ around the city’s slums. Monaghan informed the paper that it would take a million and a half pounds, approximately 4,000 and ten years eradicate the slums which honeycombed the city. In the years since 1932, approximately 766 dwellings had been erected at an expenditure of £550,000.[18] This, however was a drop in the ocean of what was required to bring housing up to standard.

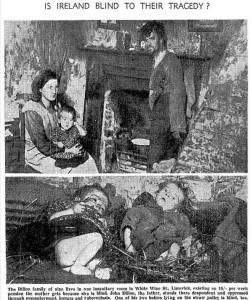

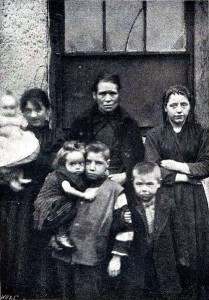

The majority of reports carried by the paper were accompanied by the obligatory pictures which have since come to symbolise what we today view as slum conditions. However, one report and accompanying set of photographs relating to a particular Limerick family really brought home the severe conditions which were prevalent in many dwellings in that city and beyond. The Dillon family of White Wine Street allowed the Press photographer to record their squalid conditions.

Living in an insanitary two-room dwelling, two of the couple’s seven children (one blind) were forced to sleep on a pallet of straw. Swathed in rags, the blind child was ‘cadaverous and pale as the sheen of death’.

The father, John Dillon was unemployed, hungry, and suffering from tuberculosis. He cut a pathetic figure, unable to properly provide for his family. Asking ‘Is Ireland Blind To Their Tragedy?’,[19] the paper called into question the very reason why Ireland had sought to become and independent nation. While by no means an exceptional case, allowing the public to see such depravation as the Dillon family were subjected to would highlight the urgent need for action.

Journalistic Opposition

Unsurprisingly rival newspapers looked unfavourably on the Irish Press crusade. The Limerick story was dismissed as ‘Stunt Journalism’ in an October edition of the Irish Independent.[20] The paper said that any attempt at such journalism would not prove effective in the matter of getting rid of slum conditions. The paper further claimed that details contained within the report on the Dillon family of White Wine Street, Limerick were fabricated or exaggerated.

It was claimed that the Dillon family received more in financial assistance than what the Irish Press had reported. It was also claimed that John Dillon was not suffering from tuberculosis, and that the family’s case was an exceptional one, which through the Irish Press article had generated ‘harmful publicity’ to the city.[21]

These claims were repeated the following month in the Irish Examiner, where it was reported that ‘some redress was due to the city by The Irish Press’. A member of the council also stated he objected ‘to any Dublin journalist coming to Limerick to dictate to the (City) Manager’.[22]

Outcomes

There had been some, not insignificant attempts to tackle the slum problem in Dublin by the time the Irish Press began its crusade. The acquisition of land in Crumlin was ordered under a compulsory purchase act by Sean T. O’Kelly on 18 August 1934. The Housing Committee wanted to build 1,100 dwellings in Crumlin and nearby Dolphins Barn within a year of the report. A total 2,328 dwellings were proposed for the whole of the Corporation’s district. This was an impressive undertaking, however there were over 11,000 applications for new accommodation during 1934.

Fianna Fail made significant efforts to tackle the housing crisis in this time, but supply of social housing never caught up with demand.

This meant that three out of every four families who applied for new accommodation would not get a new place to live. At the peak of the scheme in 1936-7 when the Press coverage began, 1000 homes were built.[1] While this had made an impact, the adverse publicity which accompanied the series of articles still highlighted an uncomfortable truth, that over a decade into life in an independent Ireland people were still living in such conditions. It also spurred some citizens into action. In Dublin, The Citizens’ Housing Council was formed out of a ‘spontaneous offer of help on the part of citizens of all shades of religious and political thought’.

On November 3, 1936 an open invitation was published calling the citizens of Dublin to action, to join this growing body and tour the slums of Dublin ‘to see with your own eyes the stark realities of the situation here where it is worst’.[23] The purpose of the council was two-fold; 1) The making of a thorough survey of conditions and the correlations of suggested remedies and 2) The creation of a public opinion which will assist local and national bodies to remove the legal, financial and other obstructions which are hampering progress.[24]

The group consisted of a number of prominent citizens such as church leaders and physicians. Interestingly, members of the Irish Press, including then Editor-In-Chief John Herlihy were also prominent members.

The group published a report in 1937 which was in turn was replied to by the Housing Committee of Dublin Corporation in the form of a report in 1938 detailing their achievements, and plans for the future.

The report highlighted what was the Corporations hopeless position, constricted by legislative and financial problems. The problem of overcrowding had become cyclical as the majority of the families re-housed by the Corporation on the basis of overcrowding were simply replaced.

The Corporation served notice on the tenement owner requiring compliance with the bye-laws (on overcrowding). The room was re-let, usually to a young couple, only for it to become overcrowded again in 2-3 years, due to natural increase. Secondly, the report quoted the Corporation’s own figures for the latest available year, 1935, showed the rate at which new dwellings were being provided (approx. 1,500 annually).

The Citizens’ Housing Council Report of 1935 concluded that the housing problem in Dublin was insoluble

On this basis the Citizens’ Housing Council Report concluded that the housing problem in Dublin was insoluble, and for the city’s slum dwellers in the 1930s the decade ended with their housing conditions little better, if not worse than those of their parents. [25]

Friction also occurred between central and local government in regard to housing. Fianna Fáil Minister for Finance, Sean MacEntee was opposed to giving Dublin Corporation the necessary funds to deal with the housing crisis. An internal memo on the 4 April 1937 to An Taoiseach, Éamon de Valera from MacEntee revealed his opposition. It sated that ‘it would be unwise to keep giving Dublin Corporation large sums of money’, and the Corporation ‘must shoulder a large part of blame themselves for not being able to finance its housing programme’.[26] It is argued that this was symptomatic of an overall hostility towards the cities from the government of the time.[27]

There were some successes in regard to housing redevelopment in the 1930s, but they were small in scale. In Cork, The Irish Builder records a commission of 28 terraced houses (probably Sarsfield’s Terrace) for Youghal UDC in 1936, as well a significant project of 82 houses in Mallow (Glenanaar and Fair Street area) to cope with the slum problem. While in Limerick, where the slums were considered on a par with Dublin and where the plight of the Dillon family garnered much publicity, seemed to have fared better in terms of redevelopment.

The redevelopment and increase in local authority housing had already begun by the time the Irish Press crusade commenced. In contrast to the 297 units of local authority housing built in 1887- 1932, 942 units were provided from 1932-40. In 1932 the Corporation built a scheme of 22 houses in the courtyard of King John’s Castle.[28]

A major housing scheme of almost 400 houses in St Mary’s Park which was completed in August 1935 went some way to eradicating the slum problem in the city. However, there was some way to go, as the Dillon case and others proved.

On completion of the St Mary’s scheme on 19 August 1935 the city’s Mayor Mr M.J. Casey stated the slums of Limerick would soon disappear with God’s help, as a scheme for the building of one thousand additional houses was at present under consideration.[29] Nevertheless, as the severity of some of the examples the paper exposed showed, it gave much needed publicity to what was happening behind closed doors.

At the Irish Press

After Frank Gallagher’s departure, the Irish Press was in something of a state of turmoil, in terms of its Editorship. Several people occupied the editor’s position in the mid-1930s, during which the paper conducted it’s ‘slum campaign’. The board of the Press would eventually return to Gallagher’s own choice of successor, Bill Sweetman.

After the brief interregnum of the mid 1930s the Irish Press resumed its close relationship with Fianna Fail.

When Sweetman was appointed in 1938, de Valera summoned him to government buildings to deliver a long lecture on Fianna Fáil policy and philosophy. Sweetman replied that there was nothing in Fianna Fáil’s policy and philosophy which conflicted with his own conscience.[30] It was clear that any editor had to conform to the party line, and in most cases the Irish Press remained steadfast in its support to Fianna Fáil.

This was clearly exhibited in relation to the paper’s promotion of the 1937 Constitution. Nevertheless, as the slum campaign demonstrated during this period the paper wasn’t afraid to draw attention to the uncomfortable realities of what was now Fianna Fáil’s Ireland.

References

[1] J. O’Reilly ‘Dublin’s Outstanding Problem’: An analysis of the debates, policies and solutions regarding the housing crisis: 1922-39 pp 26-29

[1] Ibid, p. 9

[2] J.J. Lee, Ireland 1912-1985: Politics and Society, (Cambridge, 1989), pp 168-217

[3] D Keogh, Twentieth Century Ireland: Revolution and State Building, (Dublin, 2005), p 60

[4] http://www.nli.ie/blog/index.php/2012/03/07/newspaper-descriptors-project/

[5] G. Walker, ‘The Irish Dr Goebbels’: Frank Gallagher and Irish Republican Propaganda’ in Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Jan., 1992), pp. 149-165

[6] Irish Press, 5 Sept 1931.

[7] Connolly, Sen J. (1958) Memoirs o f Senator Joseph Connolly, a Founder o f Modern

Ireland, Dublin: Irish Academic Press (1996 reprint)

[8]M. O’Brien, De Valera, Fianna Fáil and The Irish Press (Dublin, 2001), p. 67

[9] J.J. Lee, Ireland 1912-1985, p. 217

[10] M.E. Daly, The Slow Failure: Population Decline and Independent Ireland 1920-1973, p 31.

[11] R McManus, Blue Collars, “Red Forts,” and Green Fields: Working-Class Housing in Ireland in the Twentieth Century, International Labor and Working-Class History/ Volume 64 / October 2003, pp 38-54

[12] O’Brien, ‘De Valera, Fianna Fáil and The Irish Press’, p.67

[13] Maher. J, ‘The Oath Is Dead And Gone’ (Dublin, 2011), p. 136.

[14] Irish Press, 2 October 1936, p. 9

[15] Irish Press 9 Oct 1936, p 9.

[16] Ibid, p 9.

[17] Irish Press, 20 Oct 1936, p. 9

[18] Irish Press, 20 Oct 1936, p. 9

[19] Irish Press, 23 Oct 1936, p. 9

[20] Irish Independent, 26 Oct, 1936, p 3.

[21] Irish Independent, 25 Oct, 1936, p. 2.

[22] Irish Examiner, 11 Nov, 1936, p. 7.

[23] Irish Press, 3 Nov, 1936, p. 9.

[24] Irish Press, 14 Nov, 1936, p. 1

[25] F. Murphy Slums in the 1930s in Dublin Historical Record, Vol. 37, No. 3/4 (Jun. – Sep., 1984), pp. 104-111

[26] J. O’Reilly ‘Dublin’s Outstanding Problem’: An analysis of the debates, policies and solutions regarding the housing crisis: 1922-39 p. 31.

[27] M. E. Daly

[28] http://www.lThe Slow Failure: Population Decline and Independent Ireland, 1920-1973, (London, 2006), p. 49 imerickregeneration.org/NewPlan/Appendices_Social_Housing_in_Limerick_City.pdf

[29] http://www.limerickregeneration.org/stmarysparkLkLeader.html

[30] M. O’Brien, De Valera, Fianna Fáil and The Irish Press (Dublin, 2001), p. 72