‘This Splendid Historic Organisation’: The Irish Republican Brotherhood among the Anti-Treatyites, 1921-4

Daniel Murray on anti-Treaty attempts to revive the IRB during the Civil War. See also his article on the IRB after 1916.

Liam Lynch

By November 1922, five months into the Irish Civil War, Liam Lynch was a busy man as Chief of Staff to the Anti-Treatyite IRA. Not too busy, however, to turn his thoughts towards an issue that he believed needed serious consideration: the state of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). With that in mind, he wrote to one of his most trusted lieutenants, Liam Deasy. Displaying a sentimental streak, he asked Deasy for advice on how best to “save the honour of this splendid historic organisation.”

As a member of the IRB’s Supreme Council, Lynch had watched with dismay the direction the Brotherhood’s leadership had taken. With the death of Harry Boland, and the imprisonment of Joe McKelvey and Charlie Daly who had also taken the anti-Treaty line, he was now the sole remaining Council member opposed to the Treaty who was alive and at liberty.

In the middle of the civil war, Liam Lynch floated the idea of creating an anti-Treaty IRB

Determined not to let opportunities pass by, Lynch outlined to Deasy his idea that the IRB Division Council call on its secretary to reopen an adjourned meeting from before. Represented at this meeting would be the Supreme Council and a number of IRB middle-tier officers. If necessary, signatures would be taken of as many officers could be had, as most of them had been against the Treaty at the last session. Lynch was clearly aiming to go into such a showdown with the numbers loaded in his favour.

At this hypothetical congress, each member of the Supreme Council would be held to account for their sanctioning of the hated Treaty and their waging of war against fellow Republicans. The guilty individuals – and Lynch clearly had certain people in mind – would be removed, leaving the Supreme Council free to be reformed on appropriately anti-Treaty lines. If such individuals were to refuse such a meeting, the Supreme Council could be reorganised without the guilty members who would be dropped altogether.

Lynch asked Deasy to show his letter to other IRB members, including Seán O’Hegarty and Florence O’Donoghue. Although both men had taken a neutral stance for the Civil War, Lynch believed they would support him in bringing the IRB “back to the old idea.” All three of them, after all, had formed close bonds from serving together in the Cork IRA during War of Independence and remained his confidants even as they had backed away from either side in the succeeding conflict.[1]

Playing Possum

The IRB – also known as the Organisation to insiders – provides a challenge to researchers in that the sources do not necessarily provide a clear narrative. Being a secret society, it was not in its nature to advertise itself or leave convenient records for historians.

Nonetheless, some paperwork was essential to maintain communications between the various groups and individuals making up of the IRB, and enough has survived to make sense of the society as it went through one of the most turbulent times in modern Irish history.

This article does not aspire to explain the IRB at this period in its entirety at this period. Instead, it will attempt to shed some light on the thoughts of the men within the Brotherhood and what they hoped to achieve with it.

Part of the problem of studying the IRB in the later stages of the War of Independence and afterwards is that even contemporaries were not sure if this secretive fraternity was still around in any meaningful sense. It was the viewpoint of James Hogan, “on the eve of the Truce the IRB was semi-moribund beneath, and alive only on top or in its upper levels.”[2]

The IRB survived the decapitation of their leadership in 1916 but the role it played afterwards is often unclear.

As Hogan was Director of Intelligence in the Free State army, this was a substantial opinion, and one supported by others. Two of the leading figures in the Athlone IRA Brigade characterised the Organisation as falling into disuse during the later stages of the War of Independence as British efforts intensified and communications became difficult. But they also described the IRB as being revived during the breathing space provided by the Truce.[3]

This spoke of one of the Brotherhood’s great strengths: the ability to lie dormant until the pressure had slackened, allowing it to pick itself up again. It survived the Easter Rising which had seen its senior leaders executed and their replacements forced to start anew. As Liam Lynch saw it, there was no reason why the Organisation could not be recovered again, this time from its split over the Treaty.

The IRB would be condemned by critics as the instigator behind the acceptance of the fateful Treaty. Éamon de Valera cursed the machinations of “secret societies” within the Dáil as the Treaty was debated. When the Dáil ended up carrying the Treaty by a small majority, Seán T. O’Kelly held the IRB to blame, and rhetorically asked how such a crowd could be held as honest men.[4]

So there is then a certain poignancy in how Lynch, who would similarly be censured by many for leading the Anti-Treaty side into a doomed fight, did not lose his faith in the Brotherhood and what it could accomplish.

Dissent in the Ranks

Given the policy of the IRB to focus its recruitment among the IRA on officers and others with influence, it is perhaps not surprising that onlookers like James Hogan saw the Brotherhood as essentially an elitist society, one with a head but not necessarily much of a body.

It was a view that Florence O’Donoghue was keen to challenge in his later writings. To him, the IRB had been a living, active group. If there had been anything moribund about it, it was its upper tiers who had forsaken the Republic when they had accepted the Treaty.

The rank and file of the Organisation, O’Donoghue stressed, “believed with passionate intensity in the de facto existence of the Republic, and they hotly resented that any group of men, even chosen leaders, should attempt to assume the power of destroying what they had sworn to uphold.”[5]

As an example of this intensity to the point of disobedience, O’Donoghue cited a meeting of all the officers in the County Board officers and District Centres of the IRB on the 21st of January 1922. There, they protested to the Supreme Council against the latter’s support of the Treaty. “Only a high sense of duty could have driven a group of disciplined officers into such open conflict with their superiors,” was how O’Donoghue explained it, with pride and no small sense of wonder.[6]

A Democratic Conspiracy

It would be worthwhile at this point to assess how the IRB was structured. A detailed description is found in the nine-page IRB Constitution from 1920. It was marked as “revised to date”, making it the most current version that would have been available to Lynch and O’Donoghue.

The basic unit of the society was its Circles, which were divided into sections of not more than ten men each, and which elected an officer, or Centre, for the Circle.Each county in Ireland was divided into two or more Districts. Centres in each District formed a board which elected a committee for itself. Cities were enough to be considered Districts in themselves.

The basic unit of the IRB was its Circles, which were divided into sections of not more than ten men each, and which elected an officer, or Centre, for the Circle.

Further up the hierarchy were the County Centres, elected by the local Centres in each county. District Centres and County Circles were grouped into the eleven Divisions encompassing the IRB’s sphere of influence: eight Divisions for Ireland, two for the south and north halves of England, and one for Scotland.

At the apex of this pyramid was the Supreme Council. District Centres and County Circles in each Division elected by ballot a five-strong committee which in turn elected someone to represent the Division on the Supreme Council. These eleven men, one for each Division, would co-opt four additional members, leading to a total membership of fifteen for the Council.

As its name would suggest, the Supreme Council demanded, and for the most part, commanded the respect of the rest of the IRB: “The authority of the Supreme Council shall be unquestioned.” It claimed the authority to inflict punishments on errant members such as suspensions, dismissals or, in the cases of those termed treasonous, the death penalty.

But at the same time the IRB Constitution was at pains to ensure its leadership was a representative one, and that the middle and lower tiers had some say in the make-up of the ones above. It was that democratic tradition that Liam Lynch was hoping to tap into when he made his proposals to reform the Supreme Council.[7]

Florence O’Donoghue

There would be few people better qualified to critique Lynch’s views on IRB reform than O’Donoghue, having risen through the fraternity’s ranks in the months before the Truce, allowing him opportunity to observe its inner workings.

He had been an early member of the Cork IRB in the opening salvoes of the War of Independence, and had remained with it even while troubled by the issues of a dual command within the IRA that a secret society would bring.

O’Donoghue’s decision to stay with the IRB seems to have been largely based on the realisation that the Brotherhood would continue to be a deciding force behind the scenes. Which is lucky for historians, as it is in no small part due to him and his meticulous note-taking that as much is known about the IRB for this time.[8]

Florence O’Donoghue was responsible for IRB circles in Cork from March 1921.

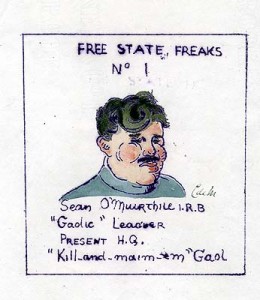

O’Donoghue was promoted to responsibility over the Circles in Cork City and the county in March 1921. A letter from Séan Ó Muirthile, a member of the Supreme Council, explained to him that Liam Lynch and he had been recommended in a high-level IRB meeting in Dublin that had included himself, Michael Collins and Liam Deasy. Although Ó Muirthile did not say, Deasy was most likely the one who pushed his fellow Corkmen forward.

As Ó Muirthile described it, O’Donoghue’s elevation to acting County Centre was a temporary one until the proper elections could be held. It was also an overdue one, as the Cork IRB was in limbo due to the loss of two of its leading lights.

Tom Hales, who had represented South Munster for the IRB as a Divisional Commander, had been arrested in July 1920 by British soldiers. His replacement, Paddy Cahill, had been unable to come from Tralee to take over, so Lynch had been asked to instead.

O’Donoghue’s role would be to replace Domhnall O’Callaghan as County Centre, as the latter had left without telling anyone, leaving the local IRB floundering. O’Callaghan’s subsequent court-martial for his dereliction of duty would be just one of the many ongoing concerns O’Donoghue would be obliged to deal with.

In addition to updating the new acting County Centre, Ó Muirthile sent O’Donoghue eight copies of general orders from the Supreme Council to distribute. Ó Muirthile comes across in his correspondence as eager to please, almost cheery, and it is sobering to think that in a little over a year’s time, the two men would be on opposing sides in the Civil War.

General Orders

Addressed “To All County Centres” and composed on behalf of the Supreme Council, the general order that Ó Muirthile told O’Donoghue to pass on provides for historians the direction the IRB leadership was planning on taking its membership. Dated to March 1921, the document opens by stressing the importance of maintaining the Organisation in a “virile and effective position throughout the country.”

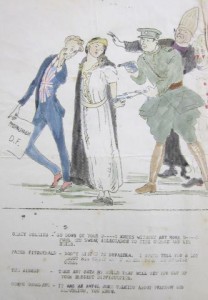

In what would have made critics like Éamon de Valera and Cathal Brugha grind their teeth, the Supreme Council took unreserved credit for making possible the current fight against the British. Continued coordination with the IRA was called for, as “the military functions of both bodies are similar to each other, the success or failing of one is the success or failure of both.”

The IRB had spent a lot of time infiltrating the IRA, and could boast of a large amount of the latter’s officers as its own. It clearly looked forward to the persistence of such an advantageous relationship. The document ended by reminding its readers that only “physical force methods” would have a chance of winning them anything.

THE IRB saw itself as an army within an army, secretly directing the IRA. Many non members were suspicious of it.

Such passages show that the Supreme Council was preparing its members for the possible continuation of the War. Also, that the IRB had no intention of stepping out of the shadows. It planned on remaining as it was before: an army within an army.

Another issue that the document addressed was that of elections throughout the levels in the IRB. The Circle elections were planned for the 15 of June 1921, the County elections on the 15th of August, and the Divisional Elections on the 15th of October. In a separate document, the County elections would be called for the 4th of November, indicating they had been pushed back. The last round of elections for the IRB had been two years ago, and the Supreme Council admitted that a lot of work would have to be made up for.

Interestingly, there seems to have been no dates set for re-electing the Supreme Council, suggesting that the democracy within the Organisation may only have been intended to go so far at this delicate stage.[9]

Treaty Reactions

O’Donoghue’s files do not indicate how these general orders were received by the Organisation audience. These files do, however, allow us insight into how some within the lower and middle ranks responded to the Treaty. By this time, O’Donoghue had gone from acting County Centre to the Divisional Secretary of South Munster, granting him supervision over the Circles in Cork, Kerry and Waterford.

The letters O’Donoghue received, or at least the ones he kept in his papers, were overwhelmingly against the Treaty. A letter from the 1st of January 1922 from a County Centre spoke of the Organisation suffering due to the uncertainty over the Treaty and an impatience for the Supreme Council to issue instructions. What was clear in this letter was that the Cork IRB was generally against the Treaty, with three District Boards forwarding resolutions to that effect.

A letter to O’Donoghue on the 10th of January from Liam Lynch, by then a recent addition to the Supreme Council, bemoaned the general lack of trust within the Council, and blamed it on the likes of Ó Muirthile and Michael Collins. The disquiet was evidently as much a feature of the upper tiers as it was of the rest of the Brotherhood.

The New Political Situation

The Supreme Council released what was for many an overdue announcement. The title, ‘The Organisation and the New Political Situation in Ireland’, showed an awareness that it was treading into uncharted waters. The document was signed for the 12th of December 1921, and issued to the rest of the Brotherhood, according to O’Donoghue, on the 12th of January.

THE IRB Supreme Council endorsed the Anglo Irish Treaty but responses throughout the organisation were more complex.

It began with a cautious, but telling, statement about how it had always been IRB policy to make use of all instruments, “political or otherwise”, towards the ultimate pursuit of the Republic. In case readers were in doubt as to what this talk of political instruments could mean, the announcement went on to state how the Supreme Council had decided that the “present peace Treaty between Ireland and Great Britain should be ratified.” The uncompromising stance from ten months back, when physical force methods were touted as the only way forward, must have seemed a long time ago.

The Supreme Council, however, appeared hesitant to push the point too far, as it allowed for IRB members doubling as TDs to vote as they saw fit on the matter. Perhaps the Council feared that to appear too domineering would push its followers into a split. Nonetheless, that was exactly what it got.[10]

Cracks Widen

Another letter from a District Centre in Cork was about a meeting held on the 18th of February 1922, where a resolution was passed expressing approval of County and Division Boards withdrawing their support from the Supreme Council over the Treaty, and calling for re-elections of the Supreme Council at the earliest date.

All of this would support O’Donoghue’s claim in his later writings that the South Munster IRB had overwhelmingly rejected the Treaty to the point of defying their leadership. This did not mean that the rebellious rank-and-file saw themselves as in opposition to the IRB as an organisation, just its Supreme Council. After all, the same resolution by the County and Division Boards condemned the Treaty in that it was contrary to the spirit of the IRB Constitution. Little wonder, then, that Liam Lynch assumed that he would have the numbers on his side when retaking control of the Supreme Council.

This attitude was not limited to the Cork IRB. A report from Co Kerry at the same period proudly told of how the Supreme Council orders had practically no effect on its Circles there, where the pro-Treaty members were very much a minority.

Otherwise, the Kerry IRB was doing well and holding regular meetings. Similarly, a report from the Waterford IRB from the 13th of January 1922 enthused about how its membership had in the past month increased considerably in size to the point of having to subdivide some Circles and create new ones.

Whatever the divisions were in the ranks and at the top, the Organisation was far from moribund. Instead, it was thriving. Little wonder, then, that Liam Lynch saw that the IRB, if properly reformed under anti-Treaty lines like many of its membership already wanted, could continue to be a great asset.[11]

The Replies

Deasy did as his Chief of Staff asked and forwarded the latter’s letter to the two neutrals, Seán O’Hegarty and Florence O’Donoghue. Deasy’s covering letter to the pair was cautiously optimistic about Lynch’s proposals, though he said he was keen to have their opinions before taking any steps.

O’Hegarty’s reply to Deasy was brief and unmoved. He had no idea at present on the subject of the IRB, and that in any case it seemed a waste to bother reorganising it while the war continued.

Disillusioned by the IRB’s response to the Treaty, Florence O’Donoghue was at first dismissive of Liam Lynch’s idea of reconstituted the IRB.

O’Donoghue’s first reply on the 2nd of December went beyond dismissive to insulting. Lynch’s idea was absurd, which surprised O’Donoghue as he thought Lynch had more sense. The IRB as it stood was too sundered to be worth much. If the current Anti-Treatyite offensive was successful, then there might be a chance to such a reorganisation, but in which case the victorious party there would be no need for an IRB anyway.

A second reply from O’Donoghue almost a month later, on the 29th of December, saw him in a more reflective and agreeable mood. He apologised for his curt tone from before, blaming it on his poor health at the time. Now he agreed with Lynch’s original points: that the IRB should be maintained to continue the fight for the Republic, and that in order for this to happen, the rotten and disloyal elements would have to be purged.

In addition, the influence of the IRB would have to be extended to include the “young virile Separatist and Republican elements”, as opposed to the “fogey” members that O’Donoghue held responsible for the disarray.

After some though O’Donoghue proposed that the IRb could be redeemed by “young virile Separatist and Republican elements”, as opposed to the “fogey” members that he held responsible for the disarray.

O’Donoghue was less sure about Lynch’s proposal to call a meeting for the Supreme Council. He feared that the pro-Treaty members already formed a majority who would stonewall any further arguments against the Treaty. It was, after all, as O’Donoghue admitted, the traditional IRB policy to use any concession by Britain as stepping-stone towards eventual Irish independence, and O’Donoghue doubted that his side had any good counter-arguments.

A more promising alternative would be to make a demand at a Supreme Council meeting – and this demand could be used as an excuse for getting the meeting agreed in the first place – for a reassembling of the complete society, with elections for a new Supreme Council by the Circles that made up the grassroots of the IRB.

O’Donoghue did not think the current Council could refuse such a demand and even if it did, the Anti-Treatyite faction would be justified in going ahead with such elections anyway, elections that O’Donoghue had no doubt would result in a Supreme Council more to their liking.

This was a more ambitious overhaul than Lynch’s, which was concerned only with the Supreme Council. O’Donoghue’s vision encompassed the whole of the IRB, a vision entirely in keeping with its Constitution, which was at pains to ensure that the leadership was a representative one.

As a side issue, such an election could also serve a secondary function as a way of ascertaining which of the Circles on paper actually existed. Keeping a society in the dark could be as much of a nuisance to those inside as it was to its opponents.[12]

Liam Deasy

O’Donoghue admitted the difficulty in implementing such a grand scheme in the present war conditions, and was at a loss for a solution unless the opportunity of another truce presented itself. Deasy was taken with O’Donoghue ideas without being put off by the latter’s doubts.

Reporting back to Lynch, Deasy doubted the adjourned meeting could be reconvened, as Lynch as suggested, repeating O’Donoghue’s anticipation that the Supreme Council would just block it.

But the call for the meeting should be made all the same, with the County Centres made aware of it. If the Supreme Council were to stymie it as expected, the County Centres could act as a temporary Council in its place until the IRB was sufficiently reoriented to hold elections for a fresh leadership. Deasy’s concern was for when, not if, this could be carried out.

Deasy ended his discussion on the topic in his letter with a request for Lynch for the names of the IRB officers in the southern area outside of South Munster – parts Deasy was evidently foggy on – in order to pass these ideas onto them.[13]

The End

There was to be no further correspondence relating to the ideas by Lynch, Deasy and O’Donoghue to take back the IRB, or, at least, none that has survived. Not that it would have made much difference in the end, as Free State forces simply steamrolled the opposition into submission. Lynch was killed on April 1923, five months after he had first aired his intention to re-establish the honour of the IRB as he saw it.

Ultimately nothing came of the proposal. What remained of the IRB remained embedded in the pro-Treaty National Army.

O’Donoghue had made the point in his first reply that if the Anti-Treatyites were to win, reforming the IRB would become an unnecessary endeavour. The Free State was to prove the truth of that initial assessment, though not in the way he had intended.

The new IRA Executive after Lynch was to be of a very different mindset to Lynch in regards to his “splendid historic organisation.” There was a meeting of eleven County Centres held on the 2nd of November 1924, eighteen months after the Civil War had officially ended. Of the eleven Centres who had been summoned, four were absent; in one case, because the man had recently died.

The Brigadier-General read out the decision of the IRA Executive for the remaining IRB Circles within the IRA to disband. From then on, the IRA alone would be sufficient, and the use for a secret society had ceased. When it came to fulfilling the role of an underground army for a republican Ireland, the post-Civil War IRA would need or brook no distractions.

There was no amendment or counter-proposal, but each of the seven Centres was anxious to state his personal view. Three agreed that the IRB had outlived itself. One also agreed that the Organisation should be disbanded but with the caveat of it being re-established at a future time if necessary.

Three disagreed with the Executive’s decision. The IRB should instead be reformed – in an unknowing echo of the late Liam Lynch – and if properly controlled, it could still uphold the “National Tradition,” as one man put it. These views revealed the emotional attachment some of the members still had for their Brotherhood even after the trials of two wars. Another dissenter argued in favour of retaining the Brotherhood on the grounds of tradition, as it had represented the ‘physical force movement’ since the time of Wolfe Tone and even at the present, it had not ceased.

But it had. The Brigadier-General recommended that the County Centres present meet with the Circle Centres under their sphere of influence to inform them of the disbandment orders. The Circle Centres would in turn pass the message on the members of their Circles. The minutes of the meeting would be sent in circulars to the Circles who had not been represented at the meeting, including those in Britain and the United States.

The IRB had been designed under its constitution to be a compromise between a top-down and down-top structure: the leadership would decide on policy but the leadership would be chosen in part by the middle and lower tiers, ensuring a mixture of discipline and representation. Now the new command was having the final say, and the membership acquiesced. Although not, it was noted, without protest.[14]

Conclusion

The Irish Republican Brotherhood in its later years is a complex picture to put together but not an impossible one. Sources such as the correspondence between Liam Lynch, Liam Deasy and Florence O’Donoghue allow historians to see how senior and long-term members who opposed the Treaty struggled to regain control of the Organisation.

The initial plan by Lynch was to reopen an adjourned meeting and use it to remove the pro-Treaty members of the Supreme Council. O’Donoghue’s extension of this idea was to call for elections that would rehaul the IRB from top to bottom. Both proposals were in keeping with the IRB Constitution that strove to create a leadership that was representative of its membership.

Files from O’Donoghue’s time as a middle-tier organiser within the IRB reveal many grassroots members as being vehemently against the Treaty, giving weight to Lynch’s and O’Donoghue’s ideas on reforming the Supreme Council. They also show the IRB stagnating in the months before the Truce before thriving afterwards in confidence and numbers. Even when the IRB Circles in the anti-Treaty IRA were disbanded in 1924, there were still members who felt a strong affinity for Ireland’s longest-running republican society.

Bibliography

National Library of Ireland – Florence O’Donoghue Papers

MS 31,233

MS 31,237(1)

MS 31,237(2)

MS 31,240

MS 31,244

Books

Ó Broin, Leon. Revolutionary Underground: The Story of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, 1858-1924 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1976)

O’Donoghue, Florence (ed. Borgonovo, John) Florence and Josephine O’Donoghue’s War of Independence (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2006)

O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin, Irish Press [1954])

Bureau of Military History Statements

O’Brien, Henry, W.S. 1308

O’Meara, Seumas, W.S. 1504

[1]National Library of Ireland (NLI), MS 31,240

[2]Ó Broin, Leon. Revolutionary Underground: The Story of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, 1858-1924 (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1976), p. 192

[3]O’Brien, Henry, (BMH / WS 1308), p.23-4 ; O’Meara, Seumas, (BMH / WS 1504), p. 53

[4] Ó Broin, pp. 198-9

[5]O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin, Irish Press [1954]), p. 194

[6]Ibid, p. 194-5

[7]NLI, MS 31,233

[8]O’Donoghue, Florence (ed. Borgonovo, John) Florence and Josephine O’Donoghue’s War of Independence (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2006) pp. 58-60

[9]NLI, MS 31,237(1)

[10] O’Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law, pp. 193-4 ; NLI, MS 31,244

[11]NLI, MS 31,237(2)

[12]NLI, MS 31,233

[13]Ibid

[14]NLI, MS MS 31,240