Frederick Engels and Ireland

Aidan Beatty on Frederick Engels’ evolving views on Ireland and the Irish in the 19th century.

Give me two hundred thousand Irishmen

and I could overthrow the entire British monarchy

Frederick Engels and the Conditions of the Irish Working Class

In May 1856, an unassuming German industrialist and his common-law Irish wife arrived in Ireland for a tour of the country. Writing to an old friend in London, another ex-patriot German, the wealthy tourist described his trip, from Dublin to Galway and down along the west coast, the landscape, and the people he met along the way.

Post-Famine Ireland was an island of ruins, some dating back to the early middle-ages, some more recent: “The land is an utter desert which nobody wants.”

The level of policing was intrusive and shocking in “England’s first colony” and “I have never seen so many gendarmes in any country… armed with carbines, bayonets and handcuffs.” Additionally, the locals, “for all their Irish fanaticism”, were being made to feel increasingly unwelcome: “By consistent oppression they have been artificially converted into an utterly impoverished nation and now, as everyone knows, fulfil the function of supplying England, America, Australia, etc., with prostitutes, casual labourers, pimps, pickpockets, swindlers, beggars and other rabble.”

Engles, co-author of the Communist Manifesto, was shocked at the poverty and repressive policing in post-famine Ireland of the 1850s

The German industrialist traveller was Friedrich Engels. His common law wife was Mary Burns (older sister of Lizzy Burns, who would later be Engels’ second wife). And his German correspondent in London was, of course, Karl Marx. Indeed, Engels ended his letter with a desire to write a History of Ireland and an admonitory request that his old comrade should visit Ireland: “Concerning the ways and means by which England rules this country – repression and corruption – long before Bonaparte attempted this, I shall write shortly if you won’t come over soon. How about it?”[1]

‘Almost without civilization’

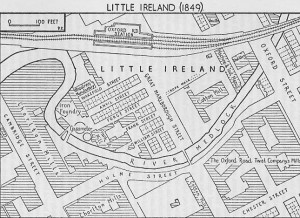

In fact, Engels had long had a fascination with the Irish (not least with regards to his two Irish wives). Echoing his observations about Irish migrant labour in his 1856 letter to Marx, his famous 1844 work on The Condition of the Working Class in England features a detailed excursus on the Irish population in Manchester’s “Little Ireland” slum district.

Engels described how Irish immigrants, with “nothing to lose at home”, were flocking to cities like Manchester in search of “good pay for strong arms”. At his time of writing, there were 40,000 Irish in Manchester, with similar numbers in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Liverpool. London had 120,000.

Yet Engels looked askance at a people who had “grown up almost without civilization” and were now importing their “rough, intemperate, and improvident” ways and “all their brutal habits” into Britain’s already overcrowded cities. The Irish arrived “like cattle” and “insinuate themselves everywhere.” In quasi-ethnographic terms, Engels claimed that “Whenever a district is distinguished for especial filth and especial ruinousness, the explorer may safely count upon meeting chiefly those Celtic faces which one recognises as different from the Saxon physiognomy.”

Frederick Engles, himself an industrialist in Manchester, in the 1840s wrote that the Irish immigrants were dirty and uncivilised.

Focusing on “filth and drunkenness” and a “lack of cleanliness… which is the Irishman’s second nature”, Engels moved into a more racialised key, perhaps revealing his own biases along the way.

“The Irishman”, Engels wrote in the singular, “loves his pig as the Arab his horse, with the difference that he sells it when it is fat enough to kill.” Bearing in mind that “Arab” in the nineteenth century referred to Bedouins, rather than any Arabic-speaking person, it is clear where Engels was placing the Irish in a broader racial hierarchy.

They were a people with “a southern facile character” and “For work which requires long training or regular, pertinacious application, the dissolute, unsteady, drunken Irishman is on too low a plane.”

They were too different, and too backward, to ever be properly assimilated into British life: “even if the Irish, who have forced their way into other occupations, should become more civilized, enough of the old habits would cling to them to have a strong degrading influence upon their English companions in toil, especially in view of the general effect of being surrounded by the Irish.”[2]

In many ways, he presented Irish immigrants to industrial Britain as exhibiting what he and Marx would later call “the idiocy of rural life”, a backward people who would soon be submerged by the dynamics of industrial capitalism.[3]

Engels admired Daniel O’Connell’s talent for popular mobilisation, but not his politics.

Yet his moralizing tone and his racial determinism could also accommodate a certain envy about Irish political power. Writing in June 1843 for Der Schweizerische Republikaner [The Swiss Republican], Engels eyed up Daniel O’Connell’s famous monster meetings with leftist jealousy:

The wily old fox gets around from town to town always surrounded by two hundred thousand men, a bodyguard such as no king can boast of. How much could be achieved if a sensible man possessed O’Connell’s popularity, or if O’Connell had a little more sense and a little less egoism and vanity! Two thousand men, and what kind of men! Men who have nothing to lose, two-thirds of them not having a shirt to their backs, they are real proletarians and sansculottes, and moreover Irishmen – wild, headstrong, fanatical Gaels. If one has not seen the Irish, one does not know them. Give me two hundred thousand Irishmen and I could overthrow the entire British monarchy.[4]

‘Revolutionary Ireland?

As Engels gained in philosophical sophistication, his use of such overtly racialized language tailed off. His earliest writings on Ireland date from only a few months after his first meeting with Marx; they had met at the offices of the Rheinische Zeitung [Rhinelander Newspaper] in November 1842, shortly after which Engels’ stern father dispatched his troublesome twenty-two year-old son to the family’s cotton mills in Manchester.[5]

First by correspondence, later in person, Marx and Engels developed their materialist understanding of history and social change. Increasingly, Engels explained people’s behaviours not in terms of inborn racial tendencies but in terms of material conditions under industrial capitalism. Nonetheless, the Irish continued to occupy a curious status for Engels. They were now the living exemplars of a pre-capitalist social formation, and visiting contemporary Ireland provided a front-row seat to the decline of feudalism and the rise of capitalism.

Marx and Engels both thought that the Irish practiced communal land-ownership before the English conquest.

In the notes for his sadly unfinished History of Ireland – begun around 1870 – Engels traced Irish economic development back to their “ancient origins”. Engels even flirted with self-taught Irish language classes for his study of Irish history, only to admit his frustration with this “philological nonsense” to Marx.[6] It was Ireland’s “obvious… misfortune”, Engels said, to be so geographically close to England, which retarded the country’s trajectory out of feudalism and into capitalism: “the English assisted nature by crushing every seed of Irish industry as soon as it appeared.”[7]

Whilst preparing for this work, Engels had come to feel that “communal ownership of land was Anno 1600 still in full force in Ireland.”[8] Pre-capitalist forms of social organisation and property-ownership lingered on in Ireland long after they had disappeared in Britain. In a letter to Marx in early 1870, Engels confessed that “The more I study the subject, the clearer it is to me that Ireland has been stunted in her development by the English invasion and thrown centuries back”.[9]

Marx had similar views. Writing in the New York Daily Tribune in 1853, he placed the restructuring of land-ownership in post-Famine Ireland in a longer history of land enclosures in early modern England and the Highland Clearances in post-1745 Scotland. In his florid journalistic prose, Marx spoke of how “the pauperised inhabits of Green Erin” were being “swept away by agricultural improvements” and by the “breaking down of the antiquated system of society.”[10] For Marx, as for Engels, Ireland still displayed traits of feudal property-ownership but was now being violently dragged into capitalist modernity. Yet, this traumatic transformation also held out a revolutionary possibility.

Engels thought the Fenians could be a force for social revolution.

In contrast to the “solid, but slow” conservatism of “the Anglo-Saxon Worker”, Irish immigrant labourers had a “revolutionary fire”.[11] Not fully schooled in the rules of private-property, they carried their essentially non-capitalist consciousness to the very heart of capitalist Britain. This was a contradiction that needed to be exploited politically. Just as he had written in Der Schweizerische Republikaner in 1843, Engels continued to feel that the Irish could be the ones to bring down the British state. Marx similarly saw Ireland as the “weakest point”[12] in the British Empire, and looked forward to a social revolution that would be “Ireland’s Revenge” upon England.[13]

Indeed, Engels and Marx were of one mind in their view that Fenianism, a product of this contradiction, could be a revolutionary force on both sides of the Irish Sea:

What the English do not yet know is that since 1846 the economic content and therefore also the political aim of English domination in Ireland have entered into an entirely new phase, and that precisely because of this, Fenianism is characterised by a socialistic tendency (in a negative sense, directed against the appropriation of the soil) and by being a lower orders movement.[14]

Which is to say, by Marx and Engels’ lights, Fenians were unconscious socialists. Giving voice to the resentments of dispossessed Irish peasants, they stood in unwitting opposition to the transformation of rural Ireland into a capitalist economy. Not that this detracted from Engels’ perception (at the time of the 1867 trial of the “Manchester Martyrs”) that the leaders of Fenianism were “mostly asses”.[15]

‘From peasant to bourgois’

Engels’ later writings, though, were less hopeful for the revolutionary future of Ireland. Visiting Ireland again in September 1869, with Lizzy Burns and Marx’s daughter, Eleanor, he saw some important changes. Dublin was now “unrecognisable”. Trade was at a high level at the port and the city had acquired a newly cosmopolitan air: “On Queenstown Quay I heard a lot of Italian, also Serbian, French and Danish or Norwegian spoken.”

‘The worst about the Irish is that they become corruptible as soon as they stop being peasants and turn bourgeois’ Frederick Engels 1869

All of this portended a regrettable conclusion: “The worst about the Irish is that they become corruptible as soon as they stop being peasants and turn bourgeois. True, that is the case with most peasant nations. But in Ireland it is particularly bad.” [16] It would appear that Ireland had made the leap from feudalism to capitalism before Engels or Marx could finish theorizing the transformation.

Indeed, in an 1888 interview with the New Yorker Volkszeitung [New Yorker People’s Newspaper], Engels confessed that “A purely socialist movement cannot be expected in Ireland for a considerable time. People there want first of all to become peasants owning a plot of land, and after they have achieved that mortgages will appear on the scene and they will be ruined once more.”[17]

Looking to a bleak future, Engels made the intriguing prophesy that for socialist revolution to take root, Ireland would have to wait for a mortgage-backed financial crisis to ruin the country – a prediction that in recent years looked strangely prescient!

References

[1] Letter from Engels to Marx, 23 May, 1856. Reprinted in full in L.I. Golman, V.E. Kunina, eds. Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Ireland and the Irish Question (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1971) 83-85.

[2] All quotes are taken from the chapter on “Irish Immigration”, in The Condition of the Working Class in England (Oxford: Oxford University Press/Oxford World Classics, 1999) 101-105.

[3] The Communist Manifesto (London: Penguin Classics, 1985) 84.

[4] ‘Letters from London’ (1843). In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 33-36.

[5] Tristram Hunt. Marx’s General: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels (New York: Henry Holt, 2009) 63-64.

[6] Letter from Friedrich Engels to Karl Marx, 19 January, 1870. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 286.

[7] Friedrich Engels, ‘History of Ireland’. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 171-209

[8] Letter from Friedrich Engels to Karl Marx, 29 November, 1869. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 279-280.

[9] Letter from Friedrich Engels to Karl Marx, 19 January, 1870. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 286.

[10] ‘New York Daily Tribune, 9 February 1853, 22 March, 1853. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 53-58.

[11] Karl Marx, ‘Confidential Communications’. Die Neue Zeit, 28 March, 1870. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 160-163.

[12] Letter from Karl Marx to Paul and Laura Lafargue, 5 March, 1870. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 290.

[13] Karl Marx. ‘Ireland’s Revenge’. Neue Oder-Zeitung, 16 March, 1855. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 74-76.

[14] Letter from Karl Marx to Friedrich Engels, 30 November , 1867. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 147.

[15] Letter from Friedrich Engels to Karl Marx, 29 November, 1867. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 145.

[16] Letter from Friedrich Engels to Karl Marx, 27 September, 1869. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 273-274

[17] 20 September, 1888. In Golman & Kunina, ‘Ireland and the Irish Question’ (1971) 343.