Women and the Achill Mission Colony

Protestant women missionaries on Achill island in the 19th century. By Patricia Byrne. (A version of this article was presented at the Heinrich Böll Memorial Weekend, Achill on 2 May 2015)

Graves Apart

If you travel to Dugort on the northern coast of Achill Island as far as St Thomas’ Church and follow the signs for the Sean Reilig up on to the slopes of Slievemore Mountain, you will arrive at what survives of an old cemetery.

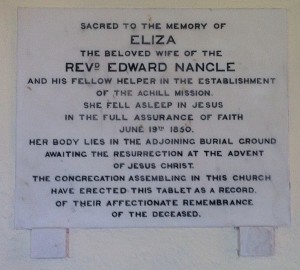

In a place where you can look out on to the waters of Blacksod Bay, you will come upon two flat boulders on which the inscriptions are barely legible. One of these marks the resting place of Eliza Nangle – wife of Edward Nangle, initiator and main driver of the nineteenth-century Achill Mission Colony.

The Nangle family are buried in old cemeteries across the breadth of Ireland

The burial spot also holds the remains of six of the Nangle children: an adult daughter, Tilly, who died suddenly in 1852, two years after her mother, and five infants who died in Achill at birth or soon afterwards.

Across the breadth of Ireland, in Row J, South Section of Deansgrange Cemetery, Monskstown, County Dublin, a gravestone has toppled to the ground at the resting spot of Edward Nangle and his second wife, Sarah. Edward had suffered a severe health breakdown as a young man and endured bouts of physical and mental ill-health throughout his life, particularly at times of stress and over-exertion.

However, he outlived his first wife by three decades. It’s possible that his frequent speaking and fundraising trips abroad, alongside his frenetic writing, acted in a therapeutic way for him while his wife had no release from the unrelenting harsh Achill conditions.

Eliza Nangle died at the age of 46. She left behind six children: three adult daughters and three sons, the youngest, a delicate boy George, just six years of age. Most of her previous sixteen years had been spent in Dugort, Achill, until poor health forced her to relocate to Dublin. From an early stage of the couple’s life in Achill, it appears that Eliza Nangle was a broken woman.

Tempestuous Years

The Nangles and their three small daughters, together with Eliza’s younger sister Grace Warner, arrived in Achill in the summer of 1834. Edward had a vision – modelled in part on the Second Reformation efforts of Lord Farnham in Cavan with ‘moral agency’ and moral reformation at its core – to convert the poverty-stricken peasants of the island through a combination of scriptural education, land reformation, employment and moral reform.

The early years of the infant Mission were tempestuous. John MacHale, Catholic Archbishop of Tuam, responded to the establishment of Mission schools by setting up competing establishments with the assistance of the new National Board of Education and the island schools became a sectarian battle ground.

The Nangles aimed to convert the islanders to Protestantism through a combination of scriptural education, land reformation, employment and moral reform.

Physical conditions in Achill were harsh, the winter storms severe, hostility toward the Colony explosive, and Edward Nangle was absent from his Dugort home for long periods on fundraising and speaking trips. On 19 April, 1835, almost a year after the family took up residence in one of the Colony’s new slated houses on the slopes of Slievemore, Eliza gave birth to a son. He lived just two days.

Soon afterwards, Dr Neason Adams – a friend of the Nangles who ran a medical practice in St Stephens Green, Dublin – relocated to Dugort with his wife Isabella at a time when the couple might have been looking forward to retirement. The Adams couple and Grace Warner would provide the main support network for Eliza for the remainder of her life.

On 11 July 1836, Eliza gave birth to a second son, Edward Neason, who survived just six weeks. A third son, George Neason, born in October 1837, died the following month. The cumulative effect of these infant deaths, alongside the growing hostility to the Colony and the vicious community conflict appear to have had a devastating effect on Eliza. Three years into the family’s life in Achill she was a shattered woman, as revealed in a letter to her sister Grace in late 1837. She would never recover her full health.

Eliza Nangle letter to her sister, Grace Warner, dated 4 December 1837.

I have so given up letter writing that to lay a letter aside, and then forget to reply to it all together, is quite an ordinary event…

I often find my heart swelling with sorrow, and my eyes filling with tears that I cannot restrain….

I trust I may become purified and made more meek for the kingdom of Christ, with whom our three dear infants abide for ever and ever.

Edward has been much spared in this owing to his absence from home. The burden rested on our affectionate friend Dr Adams. I am becoming very absent, much unfitted for the affairs of this life. My children often say to me – ‘Now Mama, do you know what you are saying; and will you remember to-morrow?’

I cannot write more now than to say, that I love you.

Your very affectionate sister,

Eliza Nangle

Achill Herald, March 1865

Protestant Evangelical Women

The women associated directly with the Achill Mission Colony – Eliza Nangle, her sister Grace Warner, Isabella Neason, and the Nangle daughters – exhibited characteristics of the nineteenth-century Protestant woman supporting and following a strong evangelical male figure. They were part of a development which saw women move out of the purely private and domestic sphere into philanthropic roles in areas such as education, orphanages, and moral improvement activities.

Like many Evangelical women of the 19th century, the Nangles asserted themselves by supporting and following a strong evangelical male figure

This enabled Protestant women of the period to move beyond the strictly domestic arena, but in a manner which did not threaten the prevalent ideals of womanhood in a patriarchal society. It was a process which had some parallels in the growth of the Catholic female religious orders in mid-nineteenth century Ireland.

The ‘moral agency’ template which Lord Farnham applied at his Cavan estate in the 1820s at the height of the Second Reformation, influenced the young curate, Edward Nangle, then resident in the nearby Arva, when he came to establish the Achill Mission.

One could say that the women at the Dugort Colony, alongside Dr Neason Adams, carried on the ‘moral agency’ function of the Mission: Isabella Neason was active in the infant school, as well as supporting her husband in his medical work; Tilly Nangle and her sisters worked in the orphanage; Eliza Nangle, in addition to carrying out book-keeping duties, also taught the skills of sewing, knitting and housekeeping/cleanliness.

It is clear that the Nangle daughters were reared in Achill in the strict traditions of a middle-class Protestant family, and the prevalent norms for Victorian women as seen in an 1838 advertisement for a Governess for the girls.

WANTED

For a Clergyman Family in Achill

A governess of active and industrious habits, experienced in tuition and attached to the Church of England, to instruct Three Children in English, French, Music, Drawing and Needlework; qualified to train them up in habits of order, and in the ways of true religion. She will also be required to cut out their Dresses, to assist in needlework, and to take charge of their wardrobe – the oldest child being under nine years of age. Salary, £25 per year.

Applications, stating references, to be made to the Rev Edward Nangle, Mission House, Achill.

Conditions for Native Achill Women

Achill in the mid-nineteenth century presented a remote, isolated, economically-deprived location. Since the Achill Sound bridge had not yet been built, travel to Newport and Westport was often undertaken by boat.

Housing in Achill was categorised as ‘fourth-class’, a classification which indicated one of the main symbols of poverty in pre-famine Ireland. The island being predominately mountain and bog with little, arable land, life was difficult and harsh.

There was no administrative or commercial centre on the island and no middle class apart from the coastguard families. Economic survival depended on seasonal migration to the harvest fields of Scotland and England to obtain cash to pay the landlord.

There was no indigenous middle class on the island and daily life was a constant struggle to pay rent to the landlord.

The most significant indicator of the position of Achill women in the mid-nineteenth century comes from the National School data for the 1830s and 1840s. It shows that only 20-25% of those enrolled in the new schooling system were female, reflecting a society attitude to women which survived into the next century. The lives of Achill women were also negatively affected by the growing authoritarian presence of the Catholic clergy in the years following Catholic Emancipation, and in the aggressive response by John MacHale and his clergy to the Achill Mission.

While Achill life for Eliza Nangle – from a sheltered, middle-class, Protestant background in County Meath – was undoubtedly grim, the contrast with the living conditions of the local island women was glaring. For one, the middle class Victorian home was her realm; for the other, the island’s land, mountains and seashores were her domain.

Achill women had poor education and lives of hard physical labour.

The Achill woman footed and saved turf and carried it from the bog on her back. She hauled seaweed from the shore, baited and gutted fish, planted and weeded potatoes, sheaved and stacked oats. In the summer months she would take over the main responsibility for farm work when many of the island man left for migrant harvesting work in Scotland and England. In the post-famine years, Achill women would themselves join the annual harvest exodus of tattie-hokers (potatoe pickers) from Achill.

Women Caught in Sectarian Crossfire

Given their subservient position, particularly in relation to literacy and linguistic skills, it is not surprising that women were caught up in the ecclesiastical crossfire between the male clerical protagonist led by Archbishop John MacHale, Edward Nangle and their clergies in Achill in the 1830s. A young island woman, Bridget Lavelle, became a servant in the Nangle household in early 1835 and, over several months, openly declared herself a Protestant.

One evening, Bridget Lavelle’s mother arrived at the Nangle house in Dugort to announce that Bridget’s eldest sister was seriously ill and wished to see Bridget before she died. When Bridget returned home, she found her sister by the fire in perfect health, and the tall figure of the new Achill Parish Priest, Father Martin Connolly, waiting. Bridget was forcibly restrained from returning to the Colony. Later, she was assisted by Edward Nangle to move secretly to Dublin where Dr Neason helped her to obtain employment.

Catholic clergy vigourously resisted efforts to convert the islanders.

The case of Margaret Reynolds, wife of the Chief Coastguard Francis Reynolds, was even more dramatic. Captain Francis Reynolds, Chief Coastguard in Achill, was a close ally of Edward Nangle with a fierce aversion to Catholicism. His wife, Margaret, mother of their seven children, was Roman Catholic and a native of Malin, County Donegal. Her position could not have been more uncomfortable as she attended mass on Sundays while her husband openly challenged the local clergy and denounced their teachings.

In December 1838, as a result of a violent altercation in Keel over access to a shipwrecked vessel, Captain Reynolds was assaulted and died two weeks later from his injuries. On 2 January 1839, his body was interred on Slievemore in a burial spot next to the graves of the Nangle infants. His widow was pregnant with their eight child.

Four days later, on the afternoon of 6th January, his body was exhumed from its grave to allow for a coroner’s inquest, and then reinterred. Within hours, a violent storm – the most severe to reach Ireland in several hundred years – swept across the country leaving hundreds dead and devastation in its wake. It was The Night of the Great Wind – Oíche na Gaoithe Móire. Margaret Reynolds gave birth to her eight child after her husband’s death. Six of their children afterwards emigrated to Reynolds’ relatives in Canada and Margaret ended her days back in Malin where she died in 1876.

Achill Famine

Eliza Nangle gave birth to two children during the famine years: a daughter, born in Achill on 10 March 1846, died at birth, as famine was taking a grip on the island. A son was still-born in December 1847 and Eliza’s health problems were by then acute.

In Dugort, Eliza Nangle and her family witnessed the calamitous consequences of the famine in its early years. We get some insight into what this experience was from the observations of Dr Neason Adams who took a leadership role in famine relief at the Achill Mission. In the Achill Herald of May 1847, Dr Adams described the crowds who gathered at the Colony seeking assistance: ‘The sick, aged, and infirm are not the only applicants for support…The cry for food is almost universal…The mournful cry of “Give me a [food] ticket – give me a [food] ticket – myself and family are starving – dying of the hunger” from morning to night never ceases round our doors and windows.’

During the Great Famine of the 1840s the Nangle raised funds to try to alleviate starvation but they also brought up orphans in the Protestant religion.

On 14 January 1846, The Telegraph carried a report that a young girl, Bridget Niland from Tyrawley, north-east Mayo, had applied for admittance to Castlebar Workhouse. According to her story, her father had taken the family to Achill where he changed his religion in return for work and food. When she refused to become a Protestant, she was beaten by her father and ran away. This incident highlights the charges of ‘souperism’ against the Achill Mission and accusations of linking famine relief to conversion and the rescinding of their Catholic faith by relief recipients.

The whole rationale of the Mission – like that of the Second Reformation efforts by Lord Farnham in Cavan – was an unbroken link between the Colony activities i.e. education, moral reform, temporal improvements, employment, and scriptural education. However, in the Great Famine period, the success of Edward Nangle’s fund-raising activities and the increase in the number of conversions heightened awareness and criticism of the linking of relief to proselytising activity. Criticism of the Colony’s orphan asylum, where Catholic children were raised as Protestants, was particularly criticised as a base method of trading in souls.

At the close of 1847, when the Famine was at its height, Eliza Nangle moved to Dublin where she spent the remaining three years of her life as her physical and mental health deteriorated. Her life in Achill was over.

‘She never was a woman of many words’

After Eliza’s death in 1850, her husband’s obituary in The Achill Herald gives us an insight, not just into Eliza’s character, but also into the prevalent views about the appropriate role of an evangelical woman of the period.

Edward described his wife’s singular skills in account keeping, which saved the Mission the expense of paying for a book-keeper over many years. He also made the unusual comment that Eliza was, ‘in every respect a woman of masculine understanding’ who devoted all her energies to the Mission, while at the same time ‘shrinking from notoriety under the shadow of her husband’s name’.

After Eliza Nangle’s death in 1850 her husband wrote she was, ‘in every respect a woman of masculine understanding’ who devoted all her energies to the Mission, while at the same time ‘shrinking from notoriety under the shadow of her husband’s name’.

While Edward Nangle was prolific and fluent in speech and writing, his wife, he wrote, was ‘never a woman of many words’. It was as if a toughness and endurance was expected of her, alongside a demureness and meekness in keeping with the prevailing ideal of womanly virtue.

Two years after her mother’s death, the Nangles’ third daughter, Tilly, died suddenly in Killiney, County Dublin while caring for her delicate brother. She was nineteen and her remains were also brought back to Achill and buried next to her mother on the slopes of Slievemore. By this stage the Nangles’ direct involvement with the Colony had come to an end as Edward had been appointed Rector of Skreen, Co Sligo. The family would continue to return to the Dugort each summer.

Isabella Adams and her husband remained on in Achill. Following a stroke, Isabella had been speechless and paralyzed for a number of years. She died on December 1855, exactly twenty years since she and her husband had relocated to the Colony.

Grace Warner did not marry and appears to have taken on a caring role, after the death of Eliza and Tilly Nangle, for Edward and Eliza’s youngest child George, who suffered from mental illness and spent much of his adult life in the North Wales Lunatic Asylum. Grace returned to Achill in her later years and died in Sheridan’s Hotel, Dugort, in 1891, four decades after the death of her only sister, and a half-century after she had landed on Dugort Strand with her brother-in-law Edward Nangle at the start of the Achill Mission.

A few years after Grace Warner’s death, in the summer of 1894, thirty-two Achill islanders drowned when the Victory hooker capsized in Clew Bay while taking migrant tattie-hokers to Westport to catch the steamer to Scotland. The majority of those who drowned were female, the youngest just twelve years old. By the end of a tumultuous century, it appeared that little had changed in the living conditions of the Achill islanders, except that Achill women had now joined the men in the annual exodus of migrant harvesters essential for island survival.

Patricia Byrne’s narrative nonfiction book The Veiled Woman of Achill – Island Outrage & A Playboy Drama is published by The Collins Press.

Further reading:

Mealla Ní Ghiobúin, Dugort, Achill Island 1831-1861: The Rise and Fall of a Missionary Community (Dublin, 2001).

Irene Whelan, The Bible War in Ireland (Wisconsin, 2005)