Travelling the Same Road? Arthur Griffith & The IRB, pre-1916

Gerard Shannon on Arthur Griffith’s long and often tortuous relationship with the Irish Republican Brotherhood up to 1916.

Gerard Shannon on Arthur Griffith’s long and often tortuous relationship with the Irish Republican Brotherhood up to 1916.

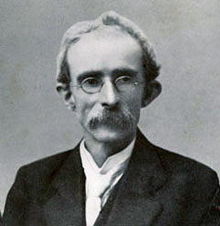

By 1905, the journalist and radical Irish separatist Arthur Griffith was keen to use his influence in advanced nationalist circles to present an alternative to the militant Irish republicanism that he had been sympathetic to in his youth.

Griffith’s proposed alternative – first, presented in a public speech and later published[1] – was a political theory that aspired towards a more passive resistance to British rule in Ireland. It became known as the ‘Sinn Féin policy’.

Drawing on his own reading of the historical example of Hungary within the Austrian Empire, Griffith proposed that Irish politicians should withdraw from the British parliament of Westminster, and re-establish ‘Grattan’s Parliament’ that had sat in Dublin and was dissolved with the passage of the Act of Union in 1800.

Though Ireland would now have its own (restored) parliament, the British monarch would remain the head of this Irish state – a concept referred to as ‘dual-monarchy’. In addition, Griffith also proposed economic ideas of protectionism and self-sufficiency for Ireland, mainly inspired by the German economist Frederick List.

Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin advocated autonomy for Ireland within a Daul Monarchy, but he retained a close association with the Republicans of the IRB.

Privately, Griffith had come to doubt the Irish public would ever truly be united in support of separatism, but felt his ideas presented a practical means of separation from Britain that could unite public opinion in Ireland.[2] Most importantly, it could potentially satisfy Irish unionists, who could point toward a symbolic connection to Britain through the reigning monarch there.

There is some evidence from his own writings that for a number of years Griffith had been slowly departing from a belief in more traditional forms of Irish republicanism. In 1899, in the pages of The United Irishman, he praised the Hungarian physical-force republican, Louis Kossuth. And yet, in the same publication, by 1903, in the midst of a published book review, Griffith remarked: “For our part, we care little whether our government be republican or monarchial so long as it be Irish, independent and just.”[3]

His policy ran counter to the beliefs of who leaned more towards the physical force tradition whose adherents made up the ranks of the secret society known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Key individuals in this organisation he would associate within the movement inspired by his ideas, the Sinn Féin political party, and yet over time would become greatly opposed to Griffith and his leadership.

What is little appreciated however, is that Griffith maintained a close association with the IRB from within and without its ranks during the decade prior to the 1916 Easter Rising; be it through funding of his various newspapers, not to mention the development of several important advanced nationalist organisations.[4]

The IRB by Griffith’s time

By the first decade of the twentieth century, the secret society known as the IRB, founded in 1858, was very much on the wane. The IRB was dedicated to the overthrow of British rule in Ireland by force, and was inspired by the secular republicanism articulated by the United Irishmen of the 1790s. Nonetheless, the organisation had experienced continued failure with physical force methods nearly half a century on from its own failed rebellion and its winding down of a bombing campaign in London in the 1880s.

The IRB’s diminished fortunes in this period came about as a result of continued splits in the 1890s amongst its sister organisation in the United States, Clan na Gael, and the split in the Irish Parliamentary Party in this decade, with whom it had been previously aligned with during the Land War of the 1880s. As a result, it had “entered into a phase of decline and became a shadow of its former self.”[5]

The IRB by 1900 was in a poor condition.

Further setting it outside the political mainstream was the IRB’s refusal to support the newly resurgent Irish Parliamentary Party under John Redmond, at a time when the IPP seemed certain of achieving its legislative goal of Home Rule – a domestic parliament for Ireland within the British Empire.

The Boer War in South Africa, from 1899 – 1902, united all strands of advanced nationalist opinion in Ireland, with a major anti-recruitment campaign in Ireland throughout the conflict. The IRB dispatched a brigade to aid the Boers led by John MacBride, and the anti-recruitment movement also brought Arthur Griffith to the fore in advanced nationalist politics.

Griffith’s Journalism

Griffith, the son of a printer family, had been a youthful admirer of the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Charles Stewart Parnell, who inspired his activism.[6] Griffith quickly became a member of the IRB at some point in this period, the organisatiation funding his very first self-published paper, The United Irishman, in 1899; forging an important business relationship that would continue for over a decade.

Griffith, the son of a printer family, had been a youthful admirer of the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Charles Stewart Parnell, who inspired his activism.[6] Griffith quickly became a member of the IRB at some point in this period, the organisatiation funding his very first self-published paper, The United Irishman, in 1899; forging an important business relationship that would continue for over a decade.

As he refined what became the ‘Sinn Féin policy’, Griffith was determined to promote these ideas in his many publications. Griffith would never be deterred by obstacles, such as the outright banning of his newspapers by British authorities, or adverse financial circumstances.

In 1906, Griffith began publishing a newspaper entitled Sinn Féin (though this confusingly was not the official organ of the similarly named movement, the Sinn Féin League, in this period). In this newspaper’s very first issue, Griffith cemented his political theories on Austria-Hungary and Grattan’s Parliament to what he felt was the definite form of Irish separatism, writing:

“The policy which Sinn Fein is born to advocate needs no lengthy exposition… It’s essential is faith… a nation’s faith in itself. It is because England has disarmed this country, because she has impoverished it, because she is strong that we write ‘humbug’ to the policy of trusting in England’s sense of justice.”[7]

Griffith as an IRB member

Griffith himself was a member of the IRB, though as befitting the difficulty of documenting a secret society, one cannot determine the exact time, being at some point around 1900. One also cannot be certain as to when he left its ranks or when his first serious rupture with the IRB began, though undoubtedly the latter was at some point prior to 1910.[8]

In a posthumous portrait, Griffith’s friend George Lyons wrote that Griffith was approached around the time of his activism for the anti-recruitment campaign in Ireland during the Boer War of 1899 – 1902. Griffith seemed to take a few months to decide whether to join – being uncertain of certain individuals who were members – but eventually did so.[9]

Whatever doubts he had, Griffith clearly demonstrated a respect for the Fenian tradition and senior figures in the movement; something he was keen to emphasise when it came to the movement funding his publications. For example, an interesting exchange that took place in 1904 is recorded between Griffith and the veteran Fenian John O’Leary, whom he had known, and revered for several years.

Griffith was recruited by the IRB as a result of his anti-recruitment agitation during the Boer War and at that time believed in the use of force to secure Irish indepndence.

If the account of the conversation is to be believed, O’Leary suggested to Griffith that Griffith’s idea of Irish separatism could only be achieved by violent revolution.

Griffith’s response is worth noting: “I have counted on that sir. The spirit of Fenianism, the soul of the historic Irish Nation, will respond at the right moment: It never failed yet.”[10]

However, Lyons felt that the “personal shyness” of Griffith, along with that of his close friend and political soul mate William Rooney (who also joined the IRB), “rendered them helpless as organisers, many whom they inspired [through their articles] becoming extremely energetic in this respect.”[11]

Lyons provides further details that Griffith was never enthusiastic about being a member of the IRB due to Fred Allen’s influence over the organisation. Allen, though Secretary of the IRB Supreme Council, was himself a member of the Dublin Corporation that welcomed Queen Victoria with a lavish reception in 1900. Though not a prominent member, Griffith appeared to share the vocal minority view within the IRB Supreme Council that this tainted Allen’s republican credentials as a result.[12]

The turning point appeared to come later when a request came from the IRB for Griffith to submit his United Irishman articles for censorship to an IRB committee in return for funds to keep the paper going. Griffith of course refused, and was nearly expelled from the organisation as a result. Lyons felt he personally prevented this at a rather dramatic meeting of the IRB Centre pointing out it was only Allen’s allies that desired Griffith’s expulsion, whereas the matter was then apparently dropped.[13]

It was likely this one incident that propelled Griffith to leave the IRB at some point before 1910, likely disturbed by this threat to the independence of his writings, but also how his membership may affect being in the leadership of a burgeoning political movement.[14]

It has also been suggested that by the time of the departure Griffith cared little for the lack of political programme on the part of the IRB, and the fact its stance on a independent republic had little traction with the general public. Moreover, with the approaching possibility of a Home Rule parliament, he was keen to exploit the possibilities of Sinn Féin as a parliamentary force there.[15]

Lyons cites a specific incident that was the final break between Griffith and his own IRB Centre. During an internal election for Lyons’ successor as Officer of Centre, Aindrias Mór Ó’Broin, was elected when Ó’Broin at the time was General Secretary of Sinn Féin. However, the Supreme Council ultimately vetoed his election. Though Lyons himself felt it was Griffith’s annoyance at this disruption of a democratic vote that was the issue rather than which individual was nominated.[16]

Nevertheless, whatever his doubts over its internal procedures, it seems Griffith saw a need for the IRB’s continued existence. In a 1900 issue of The United Irishmen, Griffith commented on secret societies that: “I do not believe [they] are in themselves good things, but I do believe they are very often necessary.”[17]

As George Lyons summaries thusly, for Griffith, when it came to the IRB: “that if their objects were not criminal, and their methods not sinful, secrecy in itself could not damn them.”[18]

Griffith and Clarke

Tom Clarke was a veteran Fenian, who had been jailed and later exiled in American for his part in a bombing campaign in England in the 1880s. His return to Ireland in 1907 would have a profound impact on the future direction of the IRB, particularly with the aid of his two chief allies in its revival, Bulmer Hobson and Sean Mac Diarmada.

The newer, younger membership that would emerge from the IRB ranks in this period would become increasingly confident in the subsequent years at challenging Griffith’s preferred strategy of political activism through the Sinn Féin party.[19] In time, it became clear that Clarke and his allies favoured a much more militant approach to Irish self-determination.

Clarke and Griffith had been firmly acquainted prior to the former’s arrival in Ireland. In 1900, Griffith through the pages of The United Irishman – in keeping with his healthy respect for the Fenian tradition – had pushed Clarke in an ultimately failed election bid to a position on Dublin Corporation. Clarke meanwhile, had acted as a selling agent for The United Irishman in New York, and in 1901, arranged speaking tours for Maude Gonne and John MacBride at Griffith’s personal suggestion.[20]

Griffith fell out with the IRB and left in around 1910.

In 1909, Clarke had become the chairman of Sinn Féin in the North Dock Ward constituency of Dublin city. Given he was a lifelong physical force republican, it should not be surprising that Clarke doubted the validity of Griffith’s Sinn Féin policy. The journalist and republican activist Sydney Gifford, in arguing with the Fenian in his Parnell Street shop, recalled Clarke as saying that he felt it was “too plodding for the Irish temperament.”[21]

Though Clarke demonstrated an appreciation for Griffith’s talents, there would at certain junctures be conflicts between both men. At one point, MacDiarmada objected to making Griffith the editor of a new IRB publication in 1915, Nationality, to which Clarke overruled him. Clarke felt Griffith’s skills proved he was best for the task, and seemed to feel Griffith would adhere to more typical IRB ideals. However, it would appear Griffith proved difficult to control, and though continuing to fund Nationality, both men were forced to create a new publication under their stewardship, The Spark.[22]

Griffith and Hobson

Griffith would have an even more troubled working relationship with the key IRB figure, Bulmer Hobson, within advanced nationalist circles. The Belfast-born Hobson was key to the formation of the Sinn Féin party in 1907, which saw several key organisations in advanced nationalism merge under the one banner.

Hobson had developed the Dungannon Clubs organisation in 1906. Though very much a recruitment front for the IRB, it claimed inspiration from the ideas laid out in Griffith’s Sinn Féin policy. The group soon became an increasingly bitter rival of the National Council, a protest body that Griffith had founded in 1903. This rivalry intensified when the Dungannon Clubs merged with Cumann na Gaedhael – an umbrella nationalist grouping Griffith had previously been involved with – to ultimately form the ‘Sinn Féin League’.[23]

With the growing popularity of the Sinn Féin policy amongst advanced Irish nationalism, Clan na Gael hoped to authorise a speaking trip of US cities for Griffith in early 1907. However, when the trip was already set in motion, IRB stalwart Patrick McCartan, writing to John Devoy, pushed instead for Hobson to be nominated instead, citing the younger man’s better public speaking ability.

Bulmer Hobson, one of the leading lights of a revived IRB and also a Sinn Féin member, had a very difficult relationship with Arthur Griffith.

Once the original plans were cancelled, Griffith rather petulantly issued a public statement from the front page of Sinn Féin saying Hobson’s trip to the US was not authorised by the executive of the National Council; indicating his own organisation could best articulate the Sinn Féin policy to the masses. Hobson, however, was completely unaware of Griffith’s anger at the situation until he met him in Dublin prior to his departure and regretted spoiling Griffith’s original plans.[24]

Nonetheless, from this juncture, a personal estrangement set in between both men, Hobson in particular feeling Griffith was no longer a true separatist.[25]

Patrick McCartan, a close ally of Hobson’s in the IRB, wrote to the Clan na Gael leader, Patrick McGarrity, to explain Griffith’s jealousy of Hobson. McCartan betrayed some of his own dislike for Griffith, likely summing the attitude of many in the IRB ranks when he wrote: “Griffith is a newspaper man. Take him out of that and he is useless… He wants men who will run to him to see what they should say… he knows Hobson would not do.”[26]

Hobson, on his return from his successful speaking tour in the US, nonetheless felt keen pressure from Irish-American backers for all advanced nationalist organisations to merge under the Sinn Féin banner. Intense discussions with the National Council, led to the latter’s merging with the Sinn Féin League by the August 1907, under the banner of Sinn Féin. Hobson and Griffith would serve as co-vice-presidents of the Sinn Féin party in 1908 and 1909, Griffith still receiving more votes then the younger man.[27]

However, the IRB stalwart, Dennis McCullough, was of the opinion that personality flaws of both Griffith and Hobson were ultimately to blame for their troubled relationship: “Hobson was a very headstrong and somewhat egotistical person, and being much younger than Griffith, the latter naturally resented Hobson endevouring to force his or our opinions on Griffith and his friends.”

Though McCullough felt that whatever conflicts existed between the two did not interfere with the strength of the Sinn Féin movement, at least during this initial period.[28]

Decline of Sinn Féin

Despite this new found unity, uneasy relations continued to endure in the Sinn Féin party between IRB figures and the more moderate grouping around Griffith. In 1909 – 10, Hobson and other key IRB figures in the party became disenchanted when Griffith almost influenced an internal party debate that could have seen Sinn Féin embrace participation in the Westminster parliament.

In early 1909, the dissident IPP MP, William O’Brien formed the All-for-Ireland League, in which he hoped to create a coalition of forces against the IPP and extreme unionism. O’Brien was interested in Sinn Féin support for contesting Dublin-based seats for a future general election, and Griffith seemed to contemplate cooperation and abandon the abstentionist policy of the party. Despite heated debate however, the proposal ultimately went nowhere.

In the end, Sinn Féin would never contest either general election in 1910, a move Griffith strongly supported. Though Griffith held little respect for John Redmond and the IPP, he did not want to disrupt the seeming inevitably of Ireland being granted a Home Rule parliament in which his party could perhaps play a part. Also, he recognised public support was on the upsurge towards the IPP. [29]

Sinn Féin had some fleeting electoral successes at local level but made no national breakthrough in the years before 1916.

Though Sinn Féin had seen some success at a local level in the intervening years, it had yet to secure a Westminster seat that – true to the party’s policy – any successful candidate would not take up if elected, true to its abstentionist policy. While Sinn Féin had lost the heated North Leitrim by-election in 1907, its success had taken many by surprise, including the party itself. From this, Griffith began to recognise the need for the Sinn Féin party to have a wider appeal to the masses, and this also led to the Sinn Féin paper briefly becoming a daily.[30]

However, Griffith’s pragmatic stance towards party policy and electorialism throughout this period ultimately resulted in the departure of the more radical, IRB rump in the party centered around Hobson, who by then already took issue with other aspects of Griffith’s autocratic style of leadership. This final break came in late 1910, as a result of the continued political and personal clashes with Griffith that now sent the party into a continued downward trend.[31]

Interestingly, Eamon Ceannt, an active member of the IRB – and future signatory of the 1916 Proclamation – would defend Griffith from these detractors. Writing in Irish Nation, Ceannt felt Griffith should be commended for trying to heal the divisions between nationalists over Home Rule; also pointing out that Griffith’s position made sense given the great public support for the Irish Parliamentary Party.[32]

When Griffith was finally elected leader of Sinn Féin in 1911, he would try to imitate the autocratic leadership of his hero, Charles Stewart Parnell. However, embracing these methods came with controversial results, mainly as Griffith lacked Parnell’s talent in this area.[33] The party would now become more of a pressure group as Griffith devoted himself to his writings.[34]

The IRB meanwhile launched a militant newspaper Irish Freedom, which often attacked Sinn Féin

Meanwhile, Hobson and his IRB allies began to devote their energies towards the republican themed-paper, Irish Freedom, funded by the IRB, which had begun publication in 1910 as a counterpoint to Griffith’s publications. An editorial in the publication in 1912 accused the Sinn Féin party for pandering to the middle classes, and forcing the removal of separatists from the party to the detriment of the movement itself.

Though the strong criticism directed towards Griffith’s Sinn Féin in the pages of Irish Freedom may have been rooted in ideological concerns, it is worth noting that Sinn Fein’s activities and membership continued to dwindle in the years 1912 – 13, demonstrating its diminished fortunes under Griffith’s leadership during this time.[35]

The general IRB disenchantment with Griffith and the Sinn Féin party by this point was indicative overall of the direction the IRB had been heading as overseen by Clarke. Combined with an upsurge in new recruits, the IRB deemed it vital to return to its roots of a militant brand of republicanism and devoted towards physical-force methods against British rule then its erosion by constitutional means.

Not too surprisingly, this new direction for the IRB occurred during a time when we can see relations between Griffith and IRB figures cooling considerably from 1910, but that changed by the outbreak of war on the European continent in 1914.[36]

The Irish Volunteers

Despite whatever clashes were occurring on the fringes of nationalism, the Irish political scene was however transformed in 1912 – 13 over the seemingly inevitable implementation of Home Rule.

The founding of the paramilitary group, the Ulster Volunteers, by Edward Carson and Ulster Unionists in January 1913, which had been set up to resist Home Rule, proved a decisive turning point in Irish politics. The prominent cultural nationalist Eoin MacNeill, writing in An Claideamh Solais that November, pushed for the founding of a similar nationalist body in an article entitled ‘The North Began’. Of course, the IRB had already begun planning for such an initiative for several months.

The Irish Volunteers were formed at a public meeting at the Rotunda in Dublin on 25th November 1913, with thousands enrolling. With MacNeill elected as chief-of-staff, the Volunteer executive itself included more notable figures of the advanced nationalists groupings, including of course, many IRB members.

Griffith was deliberately not elected to the Volunteeers Executive in 1913 for fear the organisation would “savour too much of Sinn Féin.”

However, one notable omission was Griffith himself. The Volunteers’ organiser, Michael O’Rahilly – more popularly known by his self-appointed clan name, The O’Rahilly – stated Griffith’s non-election to the Volunteers committee was intentional, the worry being that the Volunteers themselves may “savour too much of Sinn Féin.”[37]

In any case, Griffith would would go on to take the rank of an ordinary private amongst the Volunteers, being present at Howth pier as the Asgard docked on 26th July, 1914. One description of his involvement during this time mentions his tendency to have his hat cocked on one side like a Boer when with his company.[38]

Given his participation, he clearly whole-heartedly supported the formation of the Volunteers, a sentiment he expanded on in his writings. Griffith felt that the formation of such a body could prove to be a major contributory factor to creating a sense of Irish nationhood, as he explained:

“What it is going to do if guided manfully is to put public opinion with a backbone in it into the country, to make men more conscious of their duty as citizens, to associate the ideas of order and discipline with the idea of liberty, to bring the manhood of Ireland into touch with the realities, and to make it clear-seeing and fearless, to create, in fact, an atmosphere in the country in which the gas-bag and the flapdoodler will cease to be possible… A national army strong enough to hold Ireland for the Irish may eventually be evolved. All this is with God. It is the clear duty of every able-bodied man to arm in the country’s case, let the event be what it may.”[39]

The Outbreak of War

While he was clearly prepared to support the Irish Parliamentary Party tactically prior to 1914, Griffith railed against Redmond’s support for the British war effort at its outset; making reference to the National Volunteers, the pro-Redmond majority that has broken off from the Irish Volunteers:

“England is at war with Germany and Mr. Redmond has offered to England the services of the National Volunteers ‘to defend Ireland.’ What has Ireland to defend and whom has she to defend it against? Has she a native Constitution? Or a native government to defend? All know she has not.”

Griffith went on to suggest that if the British government were to pass a “full measure” of Home Rule immediately, it would give Irishmen signing up to the British war effort a reason to fight. Otherwise, “they would help to perpetuate the enslavement of their country.”[40]

Griffith argued that without Home rule being passed first, Irish participation in teh Great War amounted to “the enslavement of their country”

At the war’s outbreak, Tom Clarke convened a meeting of key individuals involved in advanced nationalism in the headquarters of the Gaelic League, where Griffith was present with other notable figures outside the political mainstream. It would appear that the prospect of a national rising was at least mooted, though not agreed on. Also, a second meeting was to have taken place, which never occurred.[41]

By September 1914, Griffith was approached by the Supreme Council of the IRB to join. Griffith refused, preferring to maintain his own independence through his publications, believing his anti-Redmondite stance would compliment their work.

However, he seemed to believe he had secured an agreement from Tom Clarke and Sean MacDiarmuida – as representatives of the IRB – that they would inform him of any development in the planning of an insurrection. As later events would prove at the outbreak of the Easter Rising, Griffith appeared to take this promise very seriously.[42]

Conclusion

Given his convoluted relationship with the IRB by 1916, it is not surprising to find Griffith had a peripheral and confused role during the Easter Rising, as this author has detailed elsewhere.

When considering any political differences between Griffith and the IRB in this period, Dennis McCullough’s thoughts are worth quoting. McCullough would complete the three-man Supreme Council along with Clarke and Mac Diarmada in 1910, later becoming President of the IRB in 1915. (Though it must be stressed both Clarke and Mac Diarmada had ensured they both really held the influence in this body).[43] McCullough stated:

“The IRB had the utmost confidence in Griffith and his strong nationalism, his courage and his integrity. He was a member of the organisation… regarded himself as travelling the same road only suggesting that ‘passive resistance’ to British rule offered better chances of success then an armed rising… no question of incompatibility between Griffith’s Hungarian Policy and the frank Republicanism of the IRB ever existed.”[44]

The general perception as indicated here is that the IRB had faith in Arthur Griffith’s bonafides as a separatist and someone they could work with – on this point P.S. O’Hegarty made clear when writing about Griffith in 1924: “… the IRB never quarreled with Griffith, but always worked with him, and recognised him for what he was, the greatest separatist force in the country.”[45]

Until Tom Clarke and Sean MacDiarmada steered the IRB towards insurrection the IRB had faith in Arthur Griffith’s bonafides as a separatist and someone they could work with.

However, there is enough to suggest the relationship between Griffith and the IRB may have been more self-serving to both parties than might have appeared to some contemporaries at the time or be admitted retrospectively. The relationship with Griffith and the IRB, according to Virginia Glandon, “fluctuated and shifted as each had greater need of the other – at times, Griffith needed IRB funds to keep his newspapers circulating and, at times, the IRB had need of Griffith’s pen.”[46]

Thus, the respective goals of the leadership of this oath-bound secret society and outspoken journalist on the fringes of Irish nationalism complimented each other as long as they existed at a similar point outside the political mainstream. Not too surprising then that this changed outright by mid-1914, when Clarke and MacDiarmada firmly steered the mechanisms of the IRB towards revolution.

And whatever promise had been made to Arthur Griffith, likely due to own stance on political violence, and almost certainly for being well outside the workings of the IRB, he would not be informed of this plan for an insurrection.

However skilled Griffith may have been in his writings, however close a working relationship it may have been before, it made no sense in the revolutionary thinking of the IRB to have this public face of advanced nationalism involved in such a risky and dangerous enterprise.

Gerard Shannon is a member of Skerries Historical Society. He can be found on Twitter at https://twitter.com/gerry_shannon and contacted by e-mail here.

References

[1] Read the full text of The Resurrection of Hungary: A Parallel for Ireland (1918) by Arthur Griffith here: https://archive.org/details/resurrectionofhu00grifiala

[2] Younger, Carlton, Arthur Griffith, Gill and MacMillian Ltd, Dublin (1981), page 28

[3] See Maye, Brian, Arthur Griffith, Griffith College Publications, Dublin (1997), pages 94, 96 and subsequent citations.

[4] For a take on Griffith’s often convoluted relationship with physical force republicans during the period covered by this article, see Glandon, Virginia E.., Arthur Griffith and the advanced nationalist press: Ireland, 1900-1922 (American University Studies), Peter Lang Gmbh, Internationaler Verlag Der Wissenschaften (1985), pages 83 – 89

[5] Kenna, Shane, Conspirators: A Photographic History of Ireland’s Revolutionary Underground, Mercier Press (2015), page 11

[6] Younger, pages 6 – 7

[7] Sinn Féin, 5th May 1906, page 1

[8] Maye, pages 112 – 113

[9] Lyons, George A., Recollections of Griffith and his times, Talbot Press, Dublin (1923), page 9

[10] Arthur Griffith Michael Collins, [Commemorative booket], Martin Lester, Dublin (1922), page 10

[11] Lyons, page 44

[12] Lyons, George, BMH/WS, page 2 – 4

[13] Lyons, George, BMH/WS page 5

[14] Younger, pages 41 – 42

[15] See both Glandon, page 85 and O’Hegarty, P.S., Classics of Irish History: The Victory of Sinn Féin – How It Won It and How It Used It, University College Press, Dublin (1998 edition), page 96.

[16] Lyons, George, BMH W/S, pages 5 – 6

[17] United Irishman, May 1900, cited on Maye, page 113

[18] Lyons, page 48

[19] Maye, page 105

[20] Maye, page 115

[21] Brennan, John, The Years Flew By: Recollections of Madame Sidney Gifford Czira, Alren House, Galway (2000 edition), page 66

[22] Glandon, pages 85 – 86

[23] For a summary of the rivalry between the Dungannon Clubs and National Council in this period, see Laffan, Michael, The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party 1916 – 23, Cambridge University Press, New York (2005), pages 21 – 25.

[24] Hay, Marie, Bulmer Hobson and the Nationalist Movement in Twentieth-Cenutry Ireland, Manchester University Press, USA (2009), page 67

[25] Younger, page 28

[26] MacAtasney, Gerard, Sean MacDiarmada: The Mind of the Revolution, Drumlin Publications, Leitrim (2004), page 25

[27] Hay, pages 71 – 73

[28] Hay, page 85

[29] Maye, pages 104 – 106; see also Younger, pages 38 – 41

[30] For an account of Sinn Féin contesting the North Leitrim by-election in 1907, see Laffan, pages 25 – 29

[31] Hay, pages 83 – 85; see also Glandon, pages 85, 88

[32] Glandon, page 62

[33] Glandon, page 88

[34] Laffan, page 32

[35] Laffan, pages 31 – 33

[36] Maye, page 115

[37] Colum, Padraic, Arthur Griffith, Browne and Nolan, Dublin (1959), page 120

[38] Aodh de Blacam in Sunday Independent, 11th September 1949, cited on Maye, page 91

[39] Sinn Féin, 22nd November 1913, cited on Maye, page 91

[40] Colum, page 131

[41] Younger, page 48; see also Brennan, Robert, BMH/WS, page 498

[42] O’Briain, Liam, BMH/WS, page 2; and the author’s own ‘The Sinn Féin Rebellion? Arthur Griffith’s Easter Week 1916’ linked here.

[43] For a brief account of how Clarke and MacDiarmada achieved this, see Laffan, page 34

[44] Glandon, page 39

[45] O’Hegarty, page 97

[46] Glandon, pages 83 – 84