“Deceived as hereafter to the destruction of both” – Stories from the 1641 Rebellion

John Dorney looks at rival Catholic accounts of the 1641 rebellion.

John Dorney looks at rival Catholic accounts of the 1641 rebellion.

The Irish insurrection of 1641-42 began with an abortive plot by Ulster Catholic gentry to seize Dublin Castle in October 1641 and ended with the formation of the Catholic Confederation and the creation of regular military units, commanded by Irish émigré officers, in the summer of 1642.

At that point, the conflict assumed the dimensions of regular war rather than a popular rebellion. By mid 1642, the Catholics seemed to be in the ascendant, with their own armies, their own government in Kilkenny and their Protestant enemies in Ireland and England divided by civil war.

But the Confederate Catholic cause was to be riven with division throughout the 1640s; over whether their primary loyalty was to the King Charles I, or to the Catholic religion. So bitter were these divisions that, by 1648, they were fighting each other.

The Confederate Catholic cause was riven with division over whether their primary loyalty was to the King Charles I, or to the Catholic religion. So bitter that, by 1648, they were fighting each other.

The split, over what terms the Confederates should sign a Treaty with the King and his Irish representative, the Earl of Ormonde, reflected deep divisions within Catholic Ireland. On the side of compromise with the Royalists in England were the wealthy, the landed and the Old English of the Pale. On the side of holding out for a self-ruled Irish state with Catholic religious dominance were many of the Gaelic Irish, particularly from Ulster and landless gentry.

After the war ended in disastrous defeat for both Royalists and Catholics with Cromwell’s invasion of the 1650s, both Confederate Catholic factions, sought to blame each other for their defeat. This piece looks at two rival Catholic accounts of this time; Richard Bellings’ History of the Confederation and War in Ireland, (written circa 1670) and The Aphorismicall Discovery of Treasonable Faction (written by an anonymous author, signed only as ‘PS’ at some time between 1652 and 1659).

Comparing their accounts of the rebellion helps us construct a picture of the confused and chaotic conditions that followed the outbreak of the rebellion. It can also trace the competing motivations, loyalties and objectives that divided the Confederates into antagonistic factions. Contrasting how Bellings (of the pro-Royalist or Omondist party) and the anonymous author (a militant anti-Ormondist) portrayed the origins of the war goes some way towards explaining the Confederate’s fatal disunity.

The Two Authors

Richard Bellings was an Old English Pale gentleman, born in 1613. His grandfather, (also named Richard Bellings) was Solicitor General for Ireland from 1574-1584, and was granted extensive lands by the Crown at Mullhuddart near Dublin in 1600. His father, Henry Bellings, served as Provost Marshal, and as High Sheriff of Wicklow County, where he campaigned in the Nine Years War against the O’Byrne clan[1]. Richard Bellings himself was trained as a lawyer at Lincoln’s Inn, London, and afterwards served in the Irish Parliament [2]. Little wonder, then, that he resented the Protestant New English monopoly on, “places of honour , profit and trust” in the Irish government, that he, as a Catholic, was barred from.[3]

Richard Bellings author of The Confederation and War in Ireland was an Old English Palesman from north County Dublin.

Little wonder also, given his family’s impeccably loyalist credentials, that he had little time for the initial (Ulster Irish) rebellion. Or, given his social standing, that he detested what modern historians call the “social rebellion”[4] but he refers to as, “the violent fury of a rude and desperate multitude”.[5] Bellings married Viscount Mountgarrett’s daughter, and was therefore related to the Ormonde dynasty and privy to the thinking of “Ormondist” nobles such as Ormonde himself, Mountgarrett and Muskerry in a way that the anonymous author was not. Furthermore, in his capacity as secretary of the Supreme Council, he was also familiar with nobles like Earl Clanricarde and James Dillon, whose thoughts and actions during 1641-42 he recounts extensively.

Finally, Bellings’ account was written in the 1670s, from the perspective of a sound royalist, whose property had been recovered after the Restoration of the monarchy. His bias therefore, is to present the rebellion as a tragic accident caused by the King’s untrustworthy ministers, and which was joined only reluctantly, and under extreme provocation, by him and his associates in the “peace party”.

The anonymous author of The Aphorismicall Discovery of Treasonable Faction was most likely a Catholic of Gaelic Irish origin.

Since he remained anonymous, we know little for certain about the background of the author of the Aphorismicall Discovery. Clearly he was an educated man – he occasionally throws in quotes from classical antiquity to prove it. He claimed to hold the Old English and Old Irish in equal affection but he was almost certainly a Gaelic Irishman.

There are several indications of this. Firstly, his brief synopsis of Irish history glorifies the resistance of the Old Irish to the English conquest (claiming that Ireland was conquered by trickery rather than force of arms) and their role as more consistent fighters on behalf of Catholicism. We can also infer this by his wholehearted approval of the rebellion, including the attacks on the New English colonists whom he calls, “English Protestant Undertakers”[6].

However, the wars of the mid-seventeenth century occurred at a time when Irish identity was shifting from being defined by language and ethnic origin (Gael against Gall) to one defined primarily by belonging to the Catholic religion. The anonymous author considered Royalist Old Englishmen such as Ormonde and Clanricarde to be sufficiently Irish to be traitors rather than simple enemies. Moreover, his examples of heroic Irish Catholics include Gaelicised Old Englishmen such as Garrett McWilliam Fitzgerald –who he tells us was, “an excellent scholar in both Latin, English and Irish” – and even Elizabethan Catholic settlers like Oliver Stephenson, whose, “only commotion was for religion” [7].

He was probably a gentleman – and derisively terms Parliamentarians, and the New English in general, as, “base and mechanical fellows”, i.e. of low un-aristocratic origin[8]. His account was written in the years between 1652 and 1659, after the total defeat of the Confederate and Royalist forces in Ireland. His primary aim is apportion blame for this defeat, which he attributes, as his title suggests, to the treachery of the peace party. His accusation is that, under the direction of Ormonde (the “prime factioner”) certain, mostly Old English, people deliberately sabotaged the Confederate war effort.

In his account of 1641-42, he tries to show how this conspiracy was present right from the outbreak of the rebellion, on the part of Ormonde’s kin and dependants, and faint-hearted Old Englishmen such as General Barry or Castlehaven. A secondary aim of the account is show that there was no distinction to be made between the Confederate and Royalist parties in Ireland. The war, for him, was against the Roundheads, Puritans and (New) English, between whom he does not make fine distinctions.

The Origins of the Rebellion

Despite their different perspectives, both men agreed that Ireland, in 1641, was a prosperous place, and had become so as a result of the 40 years of peace since the end of the Nine Years War (1594-1603). The anonymous author goes so far as to say that, “Ireland… stood in fairer terms of happiness and prosperitie than ever it had done these five hundred years, she had enjoyed the sweet fruits of a long peace, full of people and riches”[9].

Bellings, for his part emphasises the modernisation of the Irish economy, with “much improved” farms and the development of manufacturing, trade and fishing. Also, as might be expected of a lawyer, he approvingly comments that Ireland was governed by the Common Law of England (regulated by a, “free parliament”), and its people, “derived from laws an assurance of being protected as free subjects”[10].

Both Catholic authors explain their co-religionists’ grievances but only the anonymous author also complains that ‘Ireland was commanded by foreigners’.

On the long term causes of the war, the anonymous author says that Ireland was, “commanded by foreigners, and the majesty of religion eclipsed” [11]. He cites Poynings law of 1494 (which subordinated the Irish Parliament to the English one) as the most objectionable feature of this situation. Bellings details two major grievances that, “disquieted the nation” in the years leading up to the rebellion[12]. The first of these was, “the very vigorous acts… against the Catholic religion” dating from the Elizabethan period. Although these were, as yet, not strictly enforced, their presence in the law both antagonised the Catholics and frightened them with the prospect of full-scale repression in the future.

The second major grievance was plantations. This refers not to the large plantations already undertaken in Ulster and Munster, but to the constant questioning of existing land titles by government ministers. In particular, Bellings objects to the aggressive search for 200-300 year old royal titles, and the intimidation of juries to find in favour of confiscation. Although only a quarter of an estate could be confiscated in this way, the ministers responsible tended to confiscate the most valuable quarter and any estate under 100 acres was confiscated in full[13].

Bellings also states that the Old English community were now, “less free than before”. He implies that this had resulted from the ban on Catholics holding, “places of honour profit and trust” (i.e. public office). On the grievances of the initial (Ulster) plotters, Bellings records; fear of an invading Scottish or Parliamentary army, fear of the English Parliament enforcing the Penal laws in full and resentment of the Ulster plantation, which had seized lands independent of Earls Tyrone and Tyrconnell and which did not allow native Irish to purchase or lease the lands in question[14].

Both authors blame the outbreak of the war in 1641 as a defensive Catholic reaction to the rise of intolerant radical Protestantism in England and Scotland.

Despite outlining these sources of discontent, Bellings still argues that war could have been avoided in all three kingdoms had it not been for the malign influence of men who, “thought of changing their master” and ultimately, “inflamed the nation to their own destruction”[15]. Both authors argue that Ireland was destabilised by the politics of England.

Interestingly, both Bellings and the anonymous author ascribe to the English Parliament, that their objective, right from the outset, was to, “disenthrone royalty”[16] and, “upon the pretext of patronising the rights and liberties of the nation… to change the government”[17]. To destroy the monarchy in other words – a fact that was far from clear on the ground in Engalnd in 1642. They were also agreed on its intentions with regard to Ireland, which were, “the destruction of both the Catholic religion, monarchy and the Irish nation” according to the anonymous author[18], and, “the extirpation of Popery out of Ireland” according to Bellings[19]. Essentially, both saw the rebellion in Ireland as a defensive reaction to the Parliament’s threat to both the King and Irish Catholics.

Outbreak of Rebellion

The two mens’ accounts of the events that marked the outbreak of the rebellion do not differ very much. Both of them agree that the initial plot was to take Dublin Castle by stealth and having taken over the state in Ireland, to dictate their own terms to the English Parliament. Meanwhile, the northern lords were to take several towns and forts in their vicinity.

The two mens’ accounts of the events that marked the outbreak of the rebellion do not differ very much. Both of them agree that the initial plot was to take Dublin Castle by stealth and having taken over the state in Ireland, to dictate their own terms to the English Parliament. Meanwhile, the northern lords were to take several towns and forts in their vicinity.

The anonymous author alleges that Ormonde and James Dillon of Westmeath were in on the plot but lost their nerve when the conspirators were caught[20]. Bellings, who was probably in Dublin during the attempted coup, and who later had the opportunity to talk to some of the main protagonists, gives a far more detailed account.

He records how MacMahon and Maguire, having drunkenly revealed the plot to Protestant kinsmen, were betrayed to the authorities and arrested. What was more, through the exaggerated tales of O’Connelly (the main informer) or MacMahon when in custody, the Lords Justices were led to believe that the plot involved a nation-wide insurrection and a general massacre of English and Protestant inhabitants[21].

Bellings portrays the initial rebellion as a mad plot, the anonymous author as a justified taking up of arms.

This impression may have been the reason behind the State of Dublin’s heavy handed repression of the Catholic population in the following months. In fact, Bellings was told later, “by those who best knew it that there were no more than a hundred men engaged in it, for their sole end was the taking of the [Dublin] Castle”[22].

The attitudes of the two authors towards the plot and the initial rebellion differ sharply. The anonymous author does not dwell on the subject, but clearly approves of the rebellion, given that its motives were, “maintaining the Holy religion, defence of his Majesties prerogative and the vendiction of the free liberties of the Irish nation, the meere destruction and extirpation of which was intended by both states England and Ireland”.[23] He also implies that the rebels had Royal approval, saying Phelim O’Neill, “took Charlemont and several towns and holds for his Majestie’s use”[24].

Bellings, on the contrary asserts that the northern gentry involved, “took up arms blindfold” without sufficient reason, arms or support[25]. Moreover, their “sole hope” was to capture Dublin Castle, complete with its arsenal and magazine, after the failure of which they had no alternative strategy. He concedes that their plan might just have worked had they captured Dublin Castle and issued popular demands such as for the freedom of religion.

However, as it was, their failure to do this left themselves exposed to retribution of the Lords Justices and the English Parliament and left them with no choice but to try to instigate a general rebellion. As for Royal approval, Bellings asserts that it was a fraud to impress the “ignorant multitude”, and not only that, but the King’s enemies used it to “render him odious to the people [of England]”. According to Bellings, Phelim O’Neill later greatly regretted this ruse, since it led, indirectly, to the King’s execution[26].

The Disaffection of the Pale

Over the next six months, the rebellion spread from being a phenomenon localised to Ulster and parts of Wicklow to be a general insurgency throughout the country. Both authors record that initially Catholic Ireland’s political class were less than enthusiastic about the rebellion. According to the anonymous author, most of the nobility did not join, “judging the revolution of the northern people rather initiative in them than in any settled ground”[27].

Belling’s records that the Pale gentry were hostile to the rebellion, since it came from Ulster, “the seat of those disasters which formerly fell on them” – a reference to the Nine Years War. They remembered, “the desolation of those times” and feared that a new war would overturn the prosperity of the last 40 years, especially for, “those who could derive no other pretence to their estates than grants from the Crown of England” [28]. How do Bellings and the anonymous author account for the subsequent rapid spread of rebellion?

One of the key moments of the rebellion was the joining of a Gaelic Irish rebellion by “those who could derive no other pretence to their estates than grants from the Crown of England”

On the disaffection of the Pale, the anonymous author states that, having witnessed the repression carried out by, “that blood sucker Sir Charles Coote” in Wicklow and north Dublin, the Palesmen felt they, “must either tender their necks unto the merciless doom of the King’s enemies or join with Phelim O’Neill…of these two evils, they chose the last being the least”. Their final decision was reached when Phelim O’Neill arrived at the siege of Drogheda and presented his cause as being for the King, the Catholic religion and the “free liberties of the Irish nation”.

At this, the nobility drafted an oath, pledging allegiance to these objectives, and demanding of Lords Justices in Dublin that they listen to their grievances at a “free parliament” and offer an “act of oblivion for what was past”[29]. In his account, this union happened before the rebel victory at Julianstown – where the insurgents routed a hastily raised English force sent against them in November 1641.

Bellings portrays the break between Palesmen and the State as a far more tortuous affair. Firstly, he contends that the Ulster rebellion was not beyond peaceful settlement, the insurgents hoping that their contacts in the Irish Parliament, “would intercede for them”, and they, “strove to contain the raskall multitude from those frequent savage actions of stripping and killing which were after perpetrated and gave their enterprise an odious character as well in the opinion of their countrymen as of strangers”[30].

Bellings portrays the Pale as being provoked into rebellion by the heavy handed repression of the Lords Justices.

The Lords Justices, according to Bellings, removed this possible constitutional solution (of the Pale as well as Ulster gentry’s grievances) by proroguing the sitting of the of the Irish Parliament from November 11 until the 26th of February. Already, the day after the attempted coup, the Lords Justices had blamed the rebellion on, “a most disloyal and detestable conspiracy intended by some evil affected Irish Papists”. Although the Lords Justices later said they were referring only to the “meere Irish in…Ulster”, their declaration was taken as evidence of a conspiracy to persecute the, “natives and all Catholics”. [31]

Since the Lords Justices, particularly William Parsons, were already suspected of “distrust of the nation”, their decision to prorogue the Parliament convinced many, according to Bellings, that the government wanted to provoke a rebellion in order to invite over a Scottish army to, “extirpate Catholicism”. Significantly, Bellings has Ormonde pleading with the Lords Justices to convene Parliament. According to Bellings, the actions of the Dublin Government ultimately left the Palesmen with little choice but to join the rebellion, despite, “their constant fidelity in all former rebellions”, including of fighting against, “those who pretended the advancement of the Catholic religion”[32].

Firstly the Lords Justices deputised the nobility to put down the rebellion, but refused to arm them sufficiently to do so. Secondly, Charles Coote (a man who did not enjoy an affectionate relationship with Irish Catholics) murdered Catholic civilians in Wicklow, Clontarf and Santry. These actions convinced the Pale gentry that the Authorities planned a general massacre of Catholics[33]. Finally, Bellings attributes the Pale’s disaffection to their fear of a hostile Ulster rebel army (particularly after their victory at Julianstown), and Rory O’Moore’s justification of the rebellion to them as, “not rebellion and disloyalty to our King”, but to, “vindicate his rights and prerogatives from the unjust encroachments made upon them by the Malignant party of the Parliament of England”[34].

The two authors, therefore do not greatly contradict each other about this crucial phase of the rebellion. The anonymous author appears to be outside the Pale, looking in, whereas Bellings, as we know, was inside looking out. Whereas the anonymous author portrays the Pale’s defection from Government as being almost automatic, Bellings describes it as an unfortunate, belated response to great provocation on the part of the Lords Justices.

From Putsch to Popular Rebellion

On the spread of the rebellion to the rest of the country however, there is a great deal of disparity between the two writers. The anonymous author depicts the rebellion as an almost unanimous response to the circulation of the oath framed at Drogheda, when it was sent to the nobility and gentry of the country “who observing the lawfulness thereof could not choose but embrace it, hereby coming to several heads in each province”. The only obstacles were traitors such as Clanricarde and the Earl of Thomond (Barnaby O’Brien) [35].

The anonymous author depicts the rebellion as an almost unanimous response by Catholics while Bellings says it was a ‘floodgate of rapine’, by, ‘the meaner sort of people’

He claims, for example that Piers MacThomas Fitzgerald of Kildare, “observing the oath that was taken by all the Catholics of Ireland, being of one and the same religion himself, could not but adhere unto them” and marched his troops to Phelim O’Neill’s camp at Drogheda, “to his Majesty’s service’[36]. This level of co-ordination sounds fanciful, and is not mentioned by Bellings. However, according to a Lords Justices report on the 25th November 1641, a rebel oath swearing loyalty to crown, country and religion was being circulated in English and Irish[37].

The early rebellion might therefore have had greater cohesion than Bellings wished to portray. The anonymous author goes on to list the important individuals and families who took part in each locality, for example Luke O’Byrne in Wicklow, Morgan Kavanagh in Wexford and Viscount Mountgarret in Munster[38].

The early rebellion might therefore have had greater cohesion than Bellings wished to portray. The anonymous author goes on to list the important individuals and families who took part in each locality, for example Luke O’Byrne in Wicklow, Morgan Kavanagh in Wexford and Viscount Mountgarret in Munster[38].

He provides the most intimate detail of the early fighting in the midlands counties of Offally, Laois, Carlow, Kildare, Meath and Westmeath, with high praise for relatively obscure local leaders such as Art Molloy and Tadhg O’Connor.

Unlike Bellings, he makes no mention of the “social rebellion” as a destabilising factor in the countryside, nor does he mention the role of Lord President William St Ledger in Munster – whose indiscriminate killings had a similar impact to those of Charles Coote in Leinster. One reason for these omissions is probably a propagandist intention to simplify the rebellion as a noble Irish Catholic crusade, but he also simply may not have been very familiar with the situation in the south, or with the thinking of the nobility – whereas Bellings was.

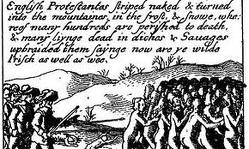

The massacres of Protestant settlers in 1641-42 has always been, both then and later, the most controversial aspect of the 1641 rebellion. For over two centuries it was portrayed in Irish Protestant discourse as a genocidal plot orchestrated by the Catholic Church. However, modern historians have attached far more importance to its social and economic roots – showing how most attacks at least initially aimed at robbing settlers and re-possessing what they considered to be confiscated land rather than killing Protestants. Resentment at the Plantations was clearly part of this but short term factors such as a poor harvest in 1641 and high levels of debt among the minor gentry were also important.

Bellings laments the killing of Protestant settlers who, “lived in profound peace among them’, while the other approvingly records the rebels “plundered and pillaged all the English Protestants that came in his way”

Bellings, presents this, “social rebellion” which he describes as, “this disease”,[39] as being central to the spread of the rebellion. He gives little space to the tensions and resentments that lay behind this violence except to say that, “the floodgate of rapine, one being laid open, the meaner sort of people was not to be contained”, and that it involved attacks on Protestant planters who, “lived in profound peace among them”[40].

Initially, he records it involved looting of English Protestant property, “rich and easy booty, taken from those seemed rather to be amazed at their loss than sensible of it”[41]. However, as the political crisis deepened, the attacks on Protestants became more violent, “several innocent souls, astonished with the madness with which their neighbours among whom they had dwelt so many years so friendly were possessed, lost their lives”[42].

The anonymous author’s attitude to the attacks on English and Protestant settlers is very different. He, unlike Bellings does not ascribe any economic motives to the attackers but alleges that those attacked had all, “declared for the Parliament”, and that this was the reason for the assaults[43]. Moreover he approvingly records incidents like the Kavanaghs burning Carlow town and, “carrying away from thence great preys and pillage”, Art Molloy killing a large number of, “English Protestant Undertakers [colonists]” at Inislaghcurhye in Offally on Stephen’s day 1641, and that Henry Dempsie, “plundered and pillaged all the English Protestants that came in his way”[44]. A reminder also, that the massacres of 1641 are not only an Ulster story.

Clearly, the “social rebellion” was a great deal more chaotic than the anonymous author makes out, but perhaps it also had greater support from the upper classes than it suited Bellings to show. What this disparity really highlights is the gap in perception between the Ormondist party – drawn from the highest echelons of Catholic Ireland, and the anti-peace party, supported in the main by those with least to lose. One viewed the attacks on Protestants and their property as a grim reminder of what could happen when, “the multitude without control did satiate their particular spleen and malice”,[45] the other as a necessary elimination of “malignant” foreigners and heretics.

The Catholic Gentry Join the Rebellion

According to Bellings, it was the spread of attacks and looting by the lower classes throughout the country that forced the nobility to take up arms. He has Clanricarde warning the gentry of Galway that, “we [are] being exposed to be destroyed by all sorts of loose and desperate people” and raising an armed body of his kin and dependants to keep the public peace[46].

Likewise, Bellings claims Richard Butler, Viscount Mountgarret, shot dead a looter of Protestants on the streets of Kilkenny, and Donagh McCarthy, Viscount Muskerry raised a large army of his tenants in southern Munster armed with skeins (knives), darts, javelins and pikes to deal with “loose fellows”[47].

What drove the nobility from keeping the peace into actual rebellion, according to Bellings was the Lords Justice’s distrust of them as Catholics, their heavy handed repression and the widespread defection from government of the nobility’s kin and local gentry. Clanricarde, according to Bellings, through his commendable loyalty to the King, managed to stand aloof from the rebellion and despite having no support from the government in Dublin secured Galway town and county for them[48]. The anonymous author, unsurprisingly, takes a very different view of Clanricarde’s actions. He states that Clanricarde treacherously prevented his family and followers from raising arms because he, “although a Catholic and an Irishman was under board (at least) against the Catholics and for the Parliament” [49].

In late 1641, most of the Irish Catholic gentry and nobility joined the uprising.and began to take control of it.

He attributes this to the fact that Clanricarde was related to the Earl of Essex – a prominent Parliamentary general. To support this, the anonymous author cites Clanricarde’s aid to the fort of Galway which was garrisoned by English troops, “knowing very well that they were members of the English Parliament and consequently against the king”[50].

Richard Butler, Viscount Mountgarret and the most powerful Catholic member of the Butler dynasty, according to Bellings, having prevented looting and sheltered Protestant refugees, was provoked into rebellion by, “the desire the Lords Justices were said to have to force men of fortune to be criminal”[51] and for fear of, “the height to which the meaner sort of people might grow up against the nobility and the gentry”[52]. Bellings states that Mountgarret was asked by the clergy and gentry to lead the rebellion in Munster to stop the depredations of St Leger and to prepare to resist the feared Scottish invasion. He agreed in order that his rebellion become, “the common cause of the nation” and to enlist and control, “loose swordsmen under regular discipline”.

Similarly Viscount Muskerry (Donagh MacCarthy) was, in Belling’s account asked by the local gentry to use his local force (raised to prevent looting) to protect them from St Leger, “ to whom they were resolved not to be reconciled”, and, “from whom they expected the greatest severity”[53].

Muskerry, to whom Bellings attributes, “excellent parts and judgement”, agonised over whether to risk his prosperous estate by rebellion. He was swung by the involvement of his friends and kinsmen, and his suspicion that the Lords Justices were secret Parliamentarians, intent on provoking war to prevent the King, “reclaiming” the Irish and using them to resist the Parliament. Incidentally, Bellings’ eulogy of Muskerry is a good example of how class transcended ethnicity in the orientation of the peace party.

The anonymous author has little to say about the outbreak of the rebellion in the south, mentioning Mountgarret only briefly and Muskerry not at all. This may have to do with his lack of familiarity with the region and with the high nobility, but in any event, he was probably reluctant to credit “Ormondist” nobles such as these with initiating of the war. Bellings, on the other hand, is at pains to point out how reluctant the nobility of the peace party were to, “fall from government”, and is also keen to disassociate them from the looting and killing of Protestants.

The anonymous author reserves his greatest hostility for Ormonde himself, alleging that he had sworn allegiance to the “Irish Confederates” and that Phelim O’Neill, “was very confident of his conjunction with them”. However Ormonde betrayed them by going over to the State having, “deceived the Irish in the very ambition of their affairs, unmindful of his sworn covenant and ungrateful to his Majesty”[54]. This analysis seems untenable – since Ormonde, a Protestant, would never have sworn to uphold the Catholic religion – and seems extremely naive.

However it is probably a ploy, both to hide the awkward fact that Ormonde was commander of Royalist forces in Ireland against the Irish Catholics, and to serve as an early indication of why the Irish should never have trusted Ormonde, who was to undermine their cause by spreading “faction” and disunity.

But Ormonde had left his family behind in Kilkenny, “to the mercy of the Irish”, and the anonymous author argues that the Irish should have held his children, “as pledges of his compliance” and that, “this would have caused him to prove more honest than he did”. Instead, Mountgarret, in his first act of treachery, let his nephew’s family travel to Dublin by sea. Bellings records that Ormonde had hurried to Dublin in the first days of the rebellion, where he has him acting as a moderating force on the Lords Justice. He confirms that some of the rebels in Kilkenny and Waterford who, “believed themselves fit for authority” wanted to hold Ormonde’s family to, “restrain the Earl, whose power they most apprehended) from being violent against them”[55].

However, Bellings commends Mountgarrett’s refusal to countenance such an action. The anonymous author further alleges that Ormonde – now working for the Parliament – sent Patrick Darcy and later Castlehaven (two prominent members of the peace party) as, “a very fit instrument to draw and work private understandings between Ormonde and his kindred and friends abroad”[56] As spies, in other words, to undermine the Confederate cause. Whereas Bellings shows Ormonde as essentially a benevolent figure, the anonymous author tailors his account of the outbreak of the rebellion to show that Ormonde should never have been trusted, and that the “peace party” was a treacherous faction planted by him in the Irish ranks.

Of the war which developed from 1642 onwards, Bellings is better informed about the south and the anonymous author about the north.

On the military encounters of 1641-42, there is a considerable disparity between the two authors. Bellings is better informed about the situation throughout the country, except, significantly, in Ulster. For example, of the siege of Drogheda and its collapse, the anonymous author says only that Phelim O’Neill raised the siege when he thought it best that commanders return to their own provinces to raise strong field armies[57]. Bellings on the contrary, recounts in detail O’Neill’s inept attempts to take the town, including the wasting of an opportunity when his men were let in by a sympathiser in the town. This badly co-ordinated assault, Bellings comments acidly, showed that, “a multitude of fresh undisciplined men are no more dextrous in surprising towns than they are skilful in besieging them”[58].

He goes on to detail the besieging Ulster Irish force’s rout at the hands of Lord Moore, when they were driven back beyond Dundalk. Bellings’ further accounts of the early campaigns are focussed on the south, where he probably fled, having been one of the Pale gentry implicated with the rebellion. The anonymous author describes the English offensive in Leinster in the spring of 1642 before switching his attention to Ulster. He places special emphasis on the atrocities of these “perfidious roundheads”, and stresses repeatedly that in the early campaigns the English and Scottish troops in Ireland gave no quarter to the Irish rebels.[59]

He also records, with great satisfaction, the death of Charles Coote at Trim, a man, “generally hated by all well or humanly affected…this is the end of the tyrant”[60]. Bellings tells of the rawness and ill-discipline of the hastily raised southern Catholic armies, particularly of the softness of the gentry, who had thought war would be, “a pleasant progress and but a change of exercise”. One Lord refused point blank to attack Dungarven saying that, “none followed him but those whom he himself had led to the service and whom he had never intended to employ in fighting against walls”[61].

“the north of Ireland, far from relief, was now bleeding… thousands of poor Irish starved in the woods, bogs, dens and caves [with the enemy] as strong as inhuman, killing without remorse all man, woman and child”

Of the major encounters of 1642 at Kilrush and Liscarroll (both Catholic defeats, respectively in Kildare and Cork), the two authors give much the same account in substance. Both agree that lack of ammunition, undisciplined troops, and weak and divided leadership were to blame for he Irish defeats. Bellings makes the telling comment about General Garret Barry, defeated at Liscarroll, that in common with other Irish, “eminent officers” he was not a born leader and performed “irregularly’ when he had to make independent decisions[62]. The anonymous author cannot resist levelling the charge of “treasonable faction” and alleges that Mountgarret deliberately lost the battle of Kilrush to his nephew Ormonde and refers to Barry as, “a great friend of the English”[63].

Furthermore, the anonymous author speaks bitterly of the desperate state of Ulster after the landing of Munro’s Scottish army in March 1642,

“the north of Ireland, far from relief, was now bleeding… thousands of poor Irish starved in the woods, bogs, dens and caves [with the enemy] as strong as inhuman, killing without remorse all man, woman and child”[64].

What was worse, the Supreme Council appeared indifferent, “not once calling to mind the bleeding wounds of Ulster”[65]. Bellings, indeed, seems unaware, at this time, of any of these events in the north. Certainly, the feeling this highlights, that the Ulster people’s sacrifice was not appreciated by the Supreme Council ,was one of the major fault-lines of the future Confederate split.

The anonymous author describes Eoghan Rua O’Neill’s arrival as, literally, a gift from God to the hard pressed Irish, whereas Bellings, who was on the Supreme Council, mentions it only in relation to the row it provoked between Eoghan Rua and Phelim O’Neill[66]. Conversely, Bellings regards the Old Englishman Thomas Preston’s arrival, in Wexford with qualified enthusiasm (qualified no doubt by Preston’s disastrous performance later in the war), where the anonymous author records sourly that the Supreme Council, “discarded Owen Roe O’Neill” in favour of the Pale gentleman Preston because they were “dubious of his greatness”[67].

An “Orderly War”

The summer of 1642 was a watershed for the war in Ireland, with the formation of the Confederation, and regular armies under its command. As Bellings comments, the rebellion, which up to this point had been marked by “freebooting”, assumed, “the appearance of the start of an orderly war”[68].

Revealingly, while both authors locate the creation of the Confederation in the need for military unity, Bellings records how the nobility and gentry of the Pale made a final attempt at reconciliation with the Lords Justices, appealing for, “an end to the devastation of their country” and the killing of their tenants and a pardon for “estated men” who had joined the “defection” through fear of the northern army[69].

A de facto Catholic government, the Confederate Catholic Association was set up in Kilkenny in May 1642, Bellings was elected to it.

It was only after the Lords Justices rebuffed their attempts and tortured to death their emissary John Read (on his way to see the King) that the Palesmen declared war on the King’s “pernicious ministers” – who, he alleges, were secretly serving the Parliament anyway. At this point, “the Catholic natives” of Ireland formed a government to, “unite the affections of the nation in prosecuting the common cause”[70]. Both men record approvingly the Clergy’s instigation of the Confederation in May 1642, including their approval of the war as “just and Godly”. The anonymous author however leaves out their condemnation of acts motivated by, “avarice, hatred, revenge or any other motive of that kind”[71].

Bellings records briefly the election of the Supreme Council (of which he was a member) and comments only of the daunting tasks which faced them, “who had no rules prescribed them”, to, “vindicate them from being thought arbritrary”[72]. For the anonymous author however, the Supreme Council was taken over from the beginning by untrustworthy “Ormondists”, elected by mistaken people who thought Ormonde would, “never be against King or nation being too far interested therein himself, but such were far deceived as hereafter to the destruction of both, and our grief will appear”.

The anonymous author alleges that the mostly Old English Supreme Council were merely pawns of their kinsman, Ormonde the Protestant Royalist leader.

Speaking of Mountgarrett, Darcy, Bellings, Garret Fennell (Ormonde’s doctor) and Muskerry, he alleges they were, “totally for Ormonde, his creatures and though sworn to the Irish Confederacy will do nothing without passing through the channels of his pleasure, as hereafter more at large”.[73]

This is certainly an exaggeration, but, as Bellings account confirms, these men clearly represented an interest that was less antagonistic to Ormonde and Protestants generally, than was the militant anti-peace party. Furthermore, the anonymous author records (and Bellings does not) that Fennell wrote a coded letter to Ormonde shortly after becoming a Supreme Councillor [74].

The anonymous author charges that right from the beginning the Supreme Council sabotaged the Confederate war effort by cashiering good colonels such as Art Molloy, Rory O’Moore and Henry Dempsy (amongst others) who, “had acted better from the outbreak of the commotions upon their own charges” and replaced them with, “those who acted nothing, were either neuters or antagonists” [75].

Bellings says of this that it was impossible to, “satisfy such a number of men as had given themselves more martial titles than could well be distributed among the officers of two or three regular armies” [76]. This analysis is probably correct, given the Confederate’s difficulty in financing their armies[77]. However, regardless of whether there was a deliberate purge of politically suspect officers on the formation of the Confederate’s regular armies, the anonymous author’s indignation at what happened is a good indication that this action was received with a great deal of discontent by future opponents of the Supreme Council.

The two authors’ respective accounts of the creation of the Confederation are designed to legitimise their version of later events. Bellings has the Supreme Council, having been fairly elected, honestly trying to solve difficult problems under trying circumstances, with at this time, the full support of the Clergy. The anonymous author on the other hand, depicts the Supreme Council as a nest of untrustworthy sycophants of the arch-traitor Ormonde.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Bellings’ and the anonymous author’s accounts of the outbreak of the rebellion tell us a great deal, not only of the events of 1641-42 but also of how these events were viewed by the adverse factions of Catholic Confederates. Bellings’ narrative is more detailed and more analytical. However he takes the opportunity to put forward (to the Restoration regime) a version of events which is most advantageous to the peace party Confederates.

Both men were Catholic Royalists, as most Confederates were, but their perspectives on the war they were fighting were very different.

He portrays the rebellion as being provoked by the injustices done to Irish Catholics and the aggression of the English Parliament, however he utterly condemns the initial rebellion itself, especially the “social rebellion” and the killings of Protestants. Moreover, he relates how reluctant the Palesmen and nobility were to join the “defection”. His bias is clearly in favour of the Old English, but as his description of Muskerry demonstrates, ethnic divisions were often transcended by class affinities in Confederate Ireland.

The anonymous author, by contrast gives unqualified support to the rebellion, including to attacks on Protestant and English settlers. He gives no indication that a, “social rebellion” took place, rather showing the extent to which the lesser gentry participated in the killings and looting of Protestants.

His affinity is primarily with the “ancient Irish”, but like Bellings, in practice, members of his “party” comprised of a range of ethnic backgrounds. The anonymous author takes every opportunity to blame Irish reverses on the treachery of the Ormonde faction and clearly is putting a retrospective spin on events. However, his allegation that the members of the peace party were not fully committed to total victory tallies to some extent with Bellings’ account of their reluctance to join the rebellion in the first place.

Furthermore, the anonymous author’s accusation of the Supreme Council’s indifference to Ulster’s problems is given credence by Bellings’ omission of them from his account. Comparison of these two versions of outbreak of the rebellion, therefore, indicate that ethnicity, class and region (north versus south) were key factors in the Confederate schism, along with the cleavage of Clergy and Nuncio against Supreme Council. The motto of the Confederation was, “Ireland unanimous, for God, King and Country”. Yet by 1648 the Catholics of Ireland were fighting each other. Examining of these conflicting accounts gives us some insight into how this came about.

Sources

- Elrington, Ball, Francis, History of the County of Dublin – Volume 6, British Society, Dublin 1902.

- O’Donoghue, D.J., Article on Richard Bellings, Catholic Encyclopaedia –

Vol. II, Robert Appleton Co., New York, 1907.

- Bellings, Richard, History of the Confederation and War in Ireland (c. 1670), in Gilbert, J.T., History of the Affairs of Ireland, Irish Archaeological and Celtic society, Dublin, 1879.

- Lenihan, Padraig, Confederate Catholics at War, Cork University Press,

Cork 2001.

- Anonymous, Aphorismicall Discovery of Treasonable Faction (c. 1652), in

Gilbert, J.T., History of the Affairs of Ireland, Irish Archaeological and Celtic society, Dublin, 1879.

- O’Siochru, Micheal, Confederate Ireland 1642-49 – A constitutional and political analysis, Four Courts Press, Dublin 1999.

References

[1] Elrington, Ball, Francis, History of the County of Dublin – Volume 6, British Society, Dublin 1902

[2] O’Donoghue, D.J., Article on Richard Bellings, Catholic Encyclopaedia – Vol. II,

[3] Bellings, Richard, History of the Confederation and War in Ireland (c. 1670), in Gilbert, J.T., History of the Affairs of Ireland, Irish Archaeological and Celtic society, Dublin, 1879, p2

[4] Lenihan, Padraig, Confederate Catholics at War, p24

[5] Bellings p32

[6] Aphorismical Discovery, Gilbert 1879, P17

[7] Ibid, pp.50, 66

[8] Ibid. P52

[9] Ibid. p1

[10] Bellings p2-3

[11] Aphorismical Discovery p1

[12] Bellings p3

[13] Ibid.

[14] Bellings pp. 2, 17

[15] Bellings p4-5

[16] Aphorismical Discovery p2

[17] Bellings p6

[18] Aphorismical Discovery p10

[19] Bellings p16

[20] Aphorismical Discovery p6

[21] Bellings p9

[22] Bellings p13

[23] Aphorismical Discovery p11

[24] Ibid. p7

[25] Bellings p7

[26] Bellings p14-18

[27] Aphorismical Discovery p7

[28] Bellings p 19

[29] Aphorismical Discovery p11

[30] Bellings p15

[31] Ibid. p18

[32] Ibid. p20-22

[33] Ibid. p44

[34] Ibid. p37

[35] Aphorismical Discovery p18

[36] Ibid. p26

[37] O’Siochru, Micheal, Confederate Ireland 1642-49 – A constitutional and political analysis, Four Courts Press, Dublin 1999, p27

[38] Aphorismical Discovery p15-16

[39] Bellings p23

[40] Bellings p14

[41] Ibid p24

[42] Ibid. p32

[43] Aphorismical Discovery p19

[44] Aphorismical Discovery p15-17

[45] Bellings p32

[46] Bellings p53

[47] Bellings pp 57, 68

[48] Ibid. p54-56

[49] Aphorismical Discovery P36

[50] Ibid. p37

[51] Bellings p55

[52] Ibid. p65

[53] Ibid. p66-69

[54] Aphorismical Discovery p33

[55] Belllings p57

[56] Aphorismical Discovery P70

[57] Ibid. p31

[58] Bellings p47

[59] Aphorismical Discovery P44

[60] Ibid. p54

[61] Bellings p72

[62] Ibid.

[63] Aphorismical Discovery, pp.49, 66

[64] Ibid. p74-75

[65] Ibid. p83

[66] Bellings p116

[67] Aphorismical Discovery p83

[68] Bellings p90

[69] Ibid. p78

[70] Bellings p79-81

[71] Cited in Bellings p87

[72] Bellings p88

[73] Aphorismical Discovery p68

[74] Ibid. p69

[75] Ibid. p73

[76] Bellings p88

[77] See Lenihan, Padraig, Confederate Catholics at War, Cork University Press, Cork 2001P51