Twenty Sixteen –Commemorating the Rising – What does it all Mean?

John Dorney on the meaning of the Easter Rising centenary.

In 2016, Ireland will mark the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising.

The Rising itself was a short but bloody insurrection in Dublin city from April 24th to 29th 1916. Just under 500 people were killed and over 2,500 injured in five days of fighting initiated by Irish separatists organised in the Irish Volunteers, who had taken over various positions around the city centre.

By the end of the week – Easter Week, from which the uprising draws its name – British forces had forced the surrender of the insurgent headquarters, who in turn ordered their other strongpoints around the city to surrender, in the words of Patrick Pearse, ‘to prevent further slaughter of the citizens’.

With the abuse of many of the self-same citizens, who were outraged that their city had been turned into a battlefield, ringing around their ears, the 1,500 or so insurgents were marched into captivity.

It could perhaps have been that the Rising would now be a mere footnote in Irish history – a relatively obscure if dramatic early 20th century event.

Instead the Easter Rising is a touchstone of national memory and identity in modern Ireland. So much so that, in 2016, 100 years on, the commemoration of the event will dominate public discourse in the Irish state in the first half of year at least. Political parties in the upcoming general election will all pay some lip service to ‘the men and women of 1916’ (50 years ago it was just ‘the men of 1916’) and claim they represent their legacy.

Why do the events in Dublin of April 1916 have such symbolic power?

Indeed there will be rival events, all claiming to be the authentic celebrants. The Irish state will have its official commemorations, involving the Taoiseach, the President and the Irish Army. What was once called the Provisional Republican movement (today Sinn Fein) will have their events – which judging by their enthusiastic recreation of the O’Donovan Rossa funeral in 2015 may well overshadow the official ones. The smaller ‘dissident’ Republican groups – still wedded to ‘armed struggle’ in Northern Ireland – will try to claim their commemorations are the only authentic ones.

The Labour party will try to claim for themselves the legacy of James Connolly and the Citizen Army – the socialist trade union militia that participated in the Rising. There will also be hundreds of local commemorative groups throughout the country who are organising marches, talks, re-enactments and the like.

The questions is; why? Why do the events in Dublin of April 1916 have such symbolic power?

The actual insurrection was after all, basically a failure. Those who launched it, basically the most militant faction of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, did not even have the support of the leader of the Volunteers – Eoin MacNeill – or the President of the IRB – Dennis McCullough. MacNeill’s attempt to call off the Rising at the last minute – his famous countermanding order – meant that there was no insurrection outside Dublin city.

The British Army brought overwhelming force to bear and crushed the Volunteers and Citizen Army within a week. There was no mass uprising accompanying the rising, no general strike to impede British forces, no mass mobilisation of the citizens of Dublin or anywhere else in favour of it. Indeed, many units of the rival National Volunteers came out to help ‘preserve order’ – in other words to aid the Crown forces – in various parts of the country.[1] Many nationalist dominated County Councils passed motions condemning the ‘mad events’ in Dublin.

The conventional answer was always that the Rising ‘woke up’ the Irish people and set them on the road towards independence. The execution of the leaders helped to turn the Irish people against the British government and to demand full independence. It was therefore a sacred event.

‘The Glorious Protest’

This view is taken up in a number of memoirs of Republican guerrilla fighters of later years. Todd Andrews for instance; ‘Dublin [in 1901] was a British city and accepted itself as one’[2] . Andrews was too honest and too down to earth a memoirist to make out the Rising changed this immediately – he was already a republican sympathiser for instance- but others did so.

For Ernie O’Malley ‘the old hatred of the redcoats had disappeared’ before the Rising. During it he at first ‘walked around in a detached manner, I had no feelings for or against’, but having seen some of the fighting experienced a kind of conversion, ‘The men down there [on the barricades] were right, that I felt sure of… No one had a right to Ireland except the Irish. In the city Irishmen were fighting British troops against long odds. I was going to help them in some way’.[3]

Tom Barry, a policeman’s son in the British Army in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) wrote that he’d had ‘no national consciousness’ but on reading of the news of the Rising, he had a ‘rude awakening ‘. ‘Guns were being fired at people of my own race by soldiers in the same army with which I was serving’. He was enthralled by the ‘beauty of the words’ of the Proclamation of the Republic. ‘Through the blood sacrifice of 1916 had one Irish youth been awakened to Irish nationality’[4].

Republican memoirists maintained that the Irish nation had been dying and the Rising ‘redeemed’ it.

PS O’Hegarty wrote in 1924, ‘at the outbreak of the European War the Irish people, swept off their feet by a wave of British propaganda…powerfully aided by the Press and the [Irish] Parliamentary Party…became anti-German and pro-British… The European War had shown Ireland to be less Irish and more Anglicised than ever she had been in her history; had shown Ireland to be three fourths assimilated to England.[5]

In such accounts, the Rising is represented as a transformational event. Before it and the martyrdom of the leaders in front of British firing squads, ‘Ireland’ was dying, her people forgetting their ‘national consciousness’ her youth serving in British uniform in the Great War. After it, Ireland was ‘reborn’, her people now, supposedly, uniformly committed to Irish independence, her youth shunning the British Army and joining the Volunteers – as O’Malley and Andrews did in 1917 and Barry later did on his return from the War.

The power of this interpretation of the Rising is that without the insurrection, Ireland as we know it would not exist. Not merely the Irish state, but Irish identity itself.

While obviously this narrative was not without some truth, at this remove we should be sceptical of it. For one thing, by the time those men and others like them came to write their memoirs, they had been through the ideological education of the Republican movement. Well before the Rising, IRB members in their newspaper Irish Freedom were arguing that the Irish nation was dying and had to be redeemed in blood.

In January 1911 for instance it wrote; ‘a nation cannot exist if a people will not respect and insist on its integrity…we are not faced with a situation in which compromise is possible’. In August 1914 it declared after the Bachelors Walk shootings, ‘the Volunteer movement has been formally baptised in the blood of Volunteers and also of British soldiers’. And in October 1914 reacting to John Redmond’s support for the British war effort; ‘He is conspiring to remove Ireland’s name from the roll of nations’.[6] Those who placed the Easter Rising at the centre of their ‘national consciousness’ were seeing it through this prism.

Was Irish nationalism really ‘dying’ for instance in Todd Andrews’ boyhood in Dublin? A Dublin where his father was a committed Parnellite and where his uncles taught him to hate ‘the informer Carey’ who had ‘betrayed’ the Invincibles’?[7] Where the Corporation – dominated by the Irish Parliamentary Party – refused to meet King George when he came to visit in 1910? A city where thousands attended rallies in support of Home Rule in 1912-14 singing ‘A Nation One Again’? No, what the separatists meant was that their particular conception of Irish identity was in danger of being marginalised – the idea that Ireland had been and would always be in a state of war with ‘England’ until she conceded full independence.

Equally, did the Rising transform all Irish people’s views? Did all the Irish Home Rule supporters instantly become republicans? Hardly. Did the Irish soldiers in the British Army desert on hearing the news of the Rising? Indeed not, despite German propaganda directed at them, very few did so. [8]

A further problem with the ‘thunderbolt’ interpretation of the Rising is that it ignores to a large degree the context in which the rising occurred – that of the continual postponement of Home Rule, the proposed partition of Ireland and the ongoing threat of conscription for British forces in the First World War. While Irish nationalists – at the urging of Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond – generally supported the British war effort in 1914, the war’s huge casualties very rapidly drained away Irish enthusiasm for it. What the separatists who opposed the Rising – principally Eoin MacNeill and Bulmer Hobson – argued was that the Volunteers should not act without mass support. They should act defensively if Britain attempted to suppress their organisation or to impose conscription.

Although both men were marginalised by their efforts to call off the Easter insurrection, events essentially proved them right. What made the Republicans into a mass national movement was not so much the Rising but the mass, mostly non-violent, campaign against conscription in the spring of 1918. Buoyed by this, the separatists, now organised in the Sinn Fein political party, gained a landslide victory in the first post-war election of December 1918.

So why, one may ask, should the Easter Rising become the transcendent symbolic event of 20th century Ireland? Why not, say, the general strike against conscription in April 1918? Or the meeting of the First Dail in January 1919 which declared Irish independence?

For this we must look more deeply into its cultural importance.

Martyrs

The fact that blood was shed in Dublin in 1916 is important. The insurgents took up arms openly and in many cases in uniform. As the ballad the Foggy Dew, composed not long afterwards, put it, ‘Right proudly high over Dublin town we hoisted our flag of war’. Against the overwhelming might of the British Empire they had only small arms, but fought bravely and honourably for a week, risking their lives, killing and dying.

There were many in the city who did not think the fight particularly honourable at the time – Volunteers sometimes shot riotous civilians whose workplaces they had occupied in the first day of the rising for instance. [9]

But this was not the point. This was a Europe that valued bravery on the battlefield. Irish republicans had been scorned as cowards and play soldiers for remaining at home while thousands of Irishmen served in British uniform. The Foggy Dew again summed up the symbolic ground broken by the Rising; ‘it was better to die ‘neath an Irish sky than at Suvla or Sud Al Bar’ [site of the Gallipoli campaign where many Irish soldiers died in 1915]. They had proved themselves, to contemporary sensibilities the equal of those prepared to die in the European war.

The martyr was someone who was put to death for their beliefs – he was ‘witness’ to the truth of his ideas.

One has to factor in also the pervasive influence in Irish Catholic culture of the martyr. The martyr is a religious trope, the word itself meaning ‘witness’. A martyr is one who suffered for their faith, died for it but refused to renounce it. The martyr was not simply someone who died in battle. The martyr was someone who was put to death for their beliefs. The implication being that before such certainty and commitment, the idea itself must be true – the martyr was ‘witness’ to the truth of his ideas. If people were willing to die for Irish independence, then surely it must be a serious cause? A holy cause even?

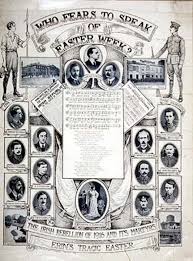

The executed leaders themselves were intensely aware of their status as martyrs. In a letter written while awaiting execution Sean McDermott for instance wrote, “I feel happiness the like of which I have never experienced. I die that the Irish nation might live!”… “I know now what I have always felt, that the Irish nation can never die … posterity will judge us aright from the effects of our actions”.[10] According to PS O’Hegarty, a participant in the Rising. ‘The Insurrection of 1916 was a forlorn hope and a deliberate blood sacrifice. The men who planned it and led it knew they could not win… But they counted on being executed afterwards and they knew that would save Ireland’s soul’.[11]

Irish nationalism already had a long standing tradition of secular martyrs, the most famous in the early 20th century being the ‘Manchester Martyrs’, three Fenians hanged in 1867 for shooting a prison guard while trying to rescue their leaders from a prison van in Manchester. The 14 men shot in May 1916 put the Manchester Martyrs forever in the shade, but the point is that the niche in the culture was already present, it just had to be filled.

Nor did the religious metaphors end there. That the Rising took place at Easter time – the Christian celebration of the resurrection of Christ – was also no coincidence. Just as Jesus had died to redeem humanity Patrick Pearse died to resurrect Ireland. Thomas Ashe, a Rising veteran who died after force-feeding on hunger strike in 1917 explicitly made this link in a poem he wrote, ‘let me carry your cross for Ireland Lord’. Growing up in the 1950s in Derry Eamon McCann recalled; ‘one learned quite literally at one’s mother’s knee, that Jesus had died for the human race and Patrick Pearse for the Irish section of it.[12]

The parallel was also immediately obvious to another group of Catholic nationalists – the Basques – who, partly for its religious analogies and partly out of admiration for the 1916 Rising placed their own national day – Aberri Eguna the day of the fatherland – on Easter Sunday in the 1920s.[13]

Acknowledging this religious imagery is not to support some contemporary commentators, who liken the psychology of the insurgents to present day Islamist extremists or jihadis, who term suicide bombing ‘martyrdom operations’.[14]

This is a senseless analogy to the Easter Rising. Though the Islamic root of ‘martyr’ – shehid – is precisely the same as the Christian one, the phenomenon of suicide bombing developed only in the 1980s. There is a difference between the willingness to die, as in 1916 and deliberately killing one’s self along with others – as in a suicide bomb. A further important difference is that jihadi organisations apparently encourage volunteers for such operations with the rewards of paradise. In 1916 the emphasis was on the sacrifice of the martyr, not their reward. Their reward they believed would be the moral effect of their sacrifice.

Thirdly and most importantly though most insurgents in 1916 were practicing Roman Catholics, in many cases devoutly so, they at no point made governing by religion or for any branch of it one of their aims. Nor were there any attacks on any minority religious or political groups during the Rising. Its political programme was purely nationalist and political.

The Changing Meaning of 1916

Above I have tried to argue for some of the reasons for the symbolic importance of 1916 as the corner stone of Irish independence, which, for practical purposes, it was not; the First Dail of 1919 or even the Treaty of 1921 or perhaps even the declaration of the Republic of Ireland in 1948 have much better claims in this regard.

The guerrilla war of 1919-21 that we now call the Irish War of Independence arguably was a much more successful military endeavour than the insurrection of 1916, but many aspects of it, such as the campaigns against the predominantly Irish Royal Irish Constabulary and the widespread shooting of civilian informers, have always produced a certain squeamishness about its commemoration.

What 1916 has that these events do not have is the power of myth – heroism, bravery, martyrdom, the rebirth of a nation.

Commemorating the Rising has proved to be extraordinarily problematic for the Irish state born in 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty

For all that, commemorating the Rising has proved to be extraordinarily problematic for the Irish state born in 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The first problem was that the 1922 settlement did not meet all the nationalist demands of 1916. Ireland was partitioned and the southern state – the Irish Free State – was originally a dominion of the British Commonwealth with the British monarch as head of state. While some of these defects were remedied over the years, the enduring fact of partition has meant that the existing, 26-county Irish state has always been vulnerable to the charge that it had ‘sold out the ideals of 1916’.

The other problem with 1916, as conventionally understood, was that a virtuous minority was understood to have taken armed action on its own, without public support but in doing so had swung public opinion around by its brave example. What was to stop armed minorities from repeating the performance, north or south of the border?

This first became apparent in 1922 during the Civil War over the treaty, when anti-Treaty republicans, decrying the argument that the Treaty was the ‘Will of People’ brought out hand bills saying, ‘if you had answered the will of the people in 1914 you would all have gone to Flanders [and the Great War]. If you had answered the will of the people in Easter Week you would have lynched Patrick Pearse’.[15].

In short, for some the lesson was that the people could sometimes get it wrong, favouring peaceful compromise over heroic national aims, and might have to shoved back into line. For a state built essentially on compromise with Britain this was an uncomfortable legacy.

Perhaps for obvious reasons the pro-Treaty Cumman na nGaedheal governments of 1923-32, (victors of the Civil War) veterans though some of them were of the 1916 Rising, kept commemorations of it somewhat low key, its implications were too militant, too uncomfortable politically.

It was only after the anti-Treaty Republicans in Fianna Fail came to power in 1932 that the Rising was celebrated bombastically, with large military parades. By the time the 50th anniversary of the Rising came around in 1966 RTE, Ireland’s then infant television station, were told that ‘the emphasis must be on celebration, on salutation’. That year saw not only huge military parades but specially commissioned television programmes and a live action pageant at Croke Park.[16]

Interestingly enough though, with the outbreak of the Northern Ireland conflict in 1968-69, the celebration of 1916 was again quickly considered too inflammatory. In 1970, the military parade was stopped and was only revived in 2006, well after the end of the Northern ‘Troubles’. In 1976, when supporters of Sinn Fein and the Provisional IRA attempted to hold their own Easter parade down Dublin’s main street, it was banned under the Offences Against the State Act. In 1991 the 75th anniversary of the Rising, there were effectively no official public commemorations in the Republic of Ireland.[17]

Some like Conor Cruise O’Brien, a prominent Labour Minister of the 1970s argued that it was the glorification of the Rising itself that caused the continuance of political violence in late 20th century Ireland; ‘violence, applied by a determined minority,’ could, in their minds, bring about unity’.[18]

Values

Despite this, popular enthusiasm for the Rising as national myth appears to be undimmed. On a recent visit to a local 1916 group in Cabra in the north of Dublin I noticed that local children had been encouraged to draw pictures of the Rising, ‘our heroes’ some of them said.

The main reason for this is that, like any symbol, the Easter Rising is capable of being made to represent a range of rival values. For instance John Hume the SDLP politician in the 1980s used the Rising to try to persuade the Provisional Republican movement to call off their armed campaign. Had Pearse not, he asked Gerry Adams, surrendered to save the lives of Dublin’s citizens in 1916? [19]

In the 1960s and before the Rising was assumed to stand for what were then the dominant national ideals – the revival of the Irish language, the moral primacy of the Catholic Church, a united Ireland. After the 1970s as Irish society became more liberal, more interest developed in the socialist and feminist ideas of some of the Rising’s participants; to the extent that today the consensus for many is that the goal of the Rising was to bring about a more equal and just society. [20]

Each new generation that commemorates the Rising invests in it their own values, hopes and desires.

The truth is that the Rising’s participants included people who believed in all of these sometimes rival and contradictory ideas but that what united them all was pursuit of Irish independence.

In 2010, with the Irish state apparently bankrupt and needing a financial bailout from the EU and IMF, the Irish Times in reference to the Rising led with a headline ‘Was it for This?’ [21] The Irish Times in 1916 was of course extremely hostile to the rebellion, but this is essentially irrelevant. What they were invoking in 2010 was the sense that 1916 represented the brave and fearless pursuit of Irish independence, now apparently again under threat.

On a more prosaic note, I can recall a primary school teacher in the early 1990s telling us that the best way to honour the memory of the executed leaders was not to litter and to keep Ireland beautiful as they would have wanted it.

This leads me to conclude that the Rising as memory, the Rising that will be commemorated in 2016, is not really about the historical event at all, but about the values that Ireland of 2016 wishes to project on to it.

References

[1] In Wexford for example, see here, but also in Sligo, see Michael Farry, the Irish Revolution Sligo p29

[2] Andrews Dublin Made Me p3

[3] Ernie O’malley on Another Man’s Wound, p31, 39, 43

[4] Tom Barry Guerrilla Days in Ireland p1-5

[5] PS O’Hegarty, the Victory of Sinn Fein p 1-3

[6] Irish Freedom archive, NLI

[7] See Andrews Dublin Made Me p23

[8] See for instance, Neil Richardson, according to Their Lights, p400-403

[9] See The Rabble and the Republic https://www.theirishstory.com/2013/08/08/the-rabble-and-the-republic/#.VoL5QbaLTGg

[10] MacAtsaney, Sean MacDiarmada, p137

[11] O’Hegarty, the Victory of Sinn Fein p3

[12] Eamonn McCann, War and an Irish Town (1993), p65

[13] For Basque–Irish links in the early 20th century, see Daniel Leach, Fugitive Ireland, European minority nationalists and Irish Political Asylum, p52-58

[14] “Though Not Quite a Jihad it was a Holy Disaster’, http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/easter-rising/how-pearse-clarke-and-co-wrote-wrongs-into-irelands-history-34301082.html In less polemical terms the link is also discussed here. https://books.google.ie/books?id=HRmYapWETqcC&pg=PA77&dq=martyrdom+easter+rising+suicide+bombers&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi9youz-oHKAhUFew8KHTxRC0IQ6AEIHjAA#v=onepage&q=martyrdom%20easter%20rising%20suicide%20bombers&f=false

[15] Capuchin archives

[16] See Cathal Brennan, A TV Pageant https://www.theirishstory.com/2010/11/18/a-tv-pageant-%E2%80%93-the-golden-jubilee-commemorations-of-the-1916-rising/#.VoLw6raLTGg

[17] See http://www.irishtimes.com/news/taoiseach-reinstates-1916-easter-parade-past-the-gpo-1.508821

[18] Cruise O’Brien, Conor, States of Ireland (London, 1974), p. 143.

[19] Brendan O’Brien, The Long War, The IRA and Sinn Fein, p19

[20] To Take just one example, Irish Times September 15 2015, ‘Are we Cherishing All the Children of the Nation Equally? http://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/second-opinion-are-we-cherishing-all-the-children-of-the-nation-1.2362906

[21] http://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/was-it-for-this-1.678424 ‘It may seem strange to some that The Irish Timeswould ask whether this is what the men of 1916 died for: a bailout from the German chancellor with a few shillings of sympathy from the British chancellor on the side. There is the shame of it all. Having obtained our political independence from Britain to be the masters of our own affairs, we have now surrendered our sovereignty to the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. Their representatives ride into Merrion Street today.’