North and South: Football and Irish Partition

The partition of Ireland is reflected in the separateness and rivalry of its two international football teams. Sathesh Alagappan looks at the background.

The Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland football teams are going through a period of relative success. Both will compete at the European Championships this summer.

Indeed, this is the first time that both teams have qualified for the same tournament. However, there will be a significant section of supporters on both sides who will not be cheering on their neighbours.

The rivalry between the North and South has a long history, seated in sectarian tensions and the history of Irish partition. However, this is not as simple as a Catholic versus Protestant conflict. At its heart, the rivalry encompasses complex ideas about identity and nationality in modern Ireland.

Pre-independence origins

Football first gained popularity in Ireland amongst its Ulster Protestant community in the North. Based in Belfast, the Irish Football Association (IFA) governed the sport in Ireland. By the late 19th century, football was increasingly played further south, but there was a perception that the IFA showed a strong Northern-bias.

For example, Southern footballers complained that selection for the national team was severely skewed. From 1882 to 1921 players from Leinster clubs won just 75 caps for the Irish national team, compared to 798 for Ulster players. Similarly, Belfast hosted almost 90% of all international matched in this period.

Partition and the battle for football sovereignty

The Partition of Ireland into North and South was first laid out by the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. The War of Independence and the Anglo-Irish Treaty followed, and by 1922, the Irish Free State was born.

These tumultuous events were the backdrop to the breakup of Irish football. In the 1921 Irish Cup, Northern side Glenavon played Dubliners Shelbourne. The first match played in Belfast ended in a draw, which should have meant a replay in Dublin in March of that year.

However, Glenavon refused to travel, citing the deteriorating security situation in the city where six Republican guerrillas were due to be executed. The IFA came down on the side of Glenavon and ruled that the replay should be played in Belfast.

Shelbourne were enraged by the decision and withdrew from the tournament. This proved to be the fatal blow to the footballing union, and later that year the Dublin based Football Association of Ireland (FAI) was born.

The split was followed by decades of tussling and uncertainty as both FAs claimed to represent the entirety of the island. The confusion was demonstrated by the fact that both teams competed under the name ‘Ireland’.

Furthermore, both reserved the right to pick players from across the border. The IFA was especially prolific at this, using generous appearance fees to persuade Southern born footballers to play for the North. Overall, there was a total of 38 ‘dual internationals’ from 1921 to 1950.

In 1949, both teams had entered qualification for the 1950 World Cup, and the practice of ‘dual internationals’ had become particularly farcical. Four Southern-born players had competed both for the Republic and the North in the qualifying campaign, leading to protestations from the FAI. FIFA were equally embarrassed by the situation and were finally prompted to deliver a resolution.

In 1953, FIFA decreed that the both nations would only be able to pick players within existing political borders. Furthermore, they decided that neither team would be able to call themselves Ireland. Rather, they would now be officially competing as the ‘Republic of Ireland’ and ‘Northern Ireland’ (though this didn’t stop the North referring to themselves as ‘Ireland’ in the Home Championships as late as 1984).

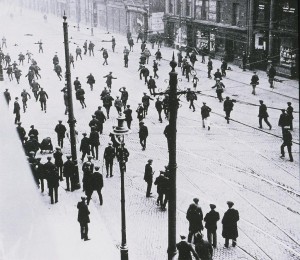

The Belfast based Irish Football Association and the Dublin based Football Association of Ireland parted company in 1921 – both claimed to represent all of Ireland.

However, recent developments have compromised this arrangement. Northern Irish residents always had the option of obtaining Irish passports, but most Northern Catholics up until recently played for the Northern team. Perhaps emboldened by the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, there has been a wave of Northern Irish Catholics opting to play for the South.

Recent examples include James McClean. Born in Derry in Northern Ireland, he had started his professional career playing for Derry City in the FAI’s League of Ireland, and represented Northern Ireland at U21 level. However, when his senior call up came, he instead opted to join the Republic. Another particularly high-profile case was Darron Gibson, whose defection prompted bitter squabbling between the two FAs, debates in Stormont, and an eventual intervention from FIFA affirming Gibson’s right to play for the Republic.

It is a part of a trend where fewer Catholic players are now represented in the Northern Irish team. Whereas the likes of Martin O’Neil and Gerry Armstrong wore the IFA’s green jersey in times gone past, the current generation are much more likely to defect. There is a feeling that the Good Friday Agreement has opened the floodgates, stimulated by continuing nationalist sentiments. This has left Northern Irish fans and officials bitter, bemoaning an ‘exodus’ from an already small nation.

The dream of reunification

Despite the differences, there have been some attempts to reunite the two teams. Perhaps the closest the teams came to this was in the 1970s, during the height of The Troubles. It had been partly prompted by high-profile figures such as the legendary Northern Irish footballer George Best. Best had made no secret of his desire play for a United Ireland, and claimed many of his teammates felt the same. They argued that the sight of Catholics and Protestants from across the island playing together could help bring communities together, and heal some of the rifts of conflict.

“The concept of one Ireland football team may be exciting but, unfortunately, it does not take account of the fact that we are living in troubled times. “ IFA President Harry Cavan.

Between 1973 and 1980 the two FAs met for a number of conferences to discuss the issue. However, an agreement was never reached. Ultimately they could not overcome political and ideological divides. It became clear that a significant number of fans in the North were hostile to the idea. With Northern Ireland increasingly drawing its support from unionists and often hardcore loyalist elements, the sight of a United Ireland in any form would prove unimaginable. Harry Cavan, the IFA president at the time, reflected this view:

“The problem with people who speak glibly of unity in Irish soccer . . . is that they tend to ignore the facts of life here in the North of Ireland. The concept of one Ireland football team may be exciting but, unfortunately, it does not take account of the fact that we are living in troubled times. “

The battle of Belfast, 1993

With reunification failing to come to fruition, the rivalry continued to develop. It reared its head in November 1993, as the two teams met in a decisive World Cup qualification match at Windsor Park.

Jack Charlton’s Republic of Ireland needed a result to book their place in the finals tournament in America. Northern Ireland were already out of contention. Yet, the prospect of knocking out their not-so-friendly neighbours was ample motivation.

The sides had already met in their first qualification tie in Dublin in March 1993, which the Republic had won 3-0. On that occasion, the home crowd had chanted ‘There’s only one team in Ireland’, much to the ire of Northern Irish management and players (no away fans were allowed to travel).

The Republic and Northern Ireland met in crucial World Cup qualifier in Belfast in 1993. The game occurred at a time of mounting violence in the North.

Events surrounding the November match also added to the tensions. In the weeks leading up to it, ceasefire negotiations were hampered by a spike in paramilitary violence. An IRA attempt to assassinate UDA leaders had led to the death of 9 Protestant civilians, in the infamous Shankill Road bombing. In retaliation, the UDA committed the Greysteel Massacre, where 8 Catholic civilians were shot down in a crowded Londonderry pub. Six other Catholics were killed in other attacks that week. Northern Ireland was spiralling into chaos.

In this context, many feared that the match could act as a release-valve for further sectarian conflict. Police swarmed around Windsor Park that evening, which is located in a staunchly loyalist area of Belfast. The Republic of Ireland team were virtually cordoned off in their hotel for their own safety before the match.

Inside Windsor Park, the atmosphere reached fever pitch. Virtually every touch of the ball by a Republic of Ireland player was greeted with a chorus of ‘Fenian bastards’, accompanied by chants referencing the Greysteel massacre. The Northern Irish manager Billy Bingham did little to help, at one point leading the crowd in singing the Orange Order anthem ‘The Sash’. The Windsor Park crowd at other times sang the ‘Billy Boys’, a sectarian anthem that included the line ‘we’re up to our necks in Fenian blood’.

“You didn’t dare look around and make eye contact. The venom in their eyes shocked me.” ROI International Alan McLoughlin.

A player who faced particular vitriol on the pitch was Alan Kernaghan. Kernaghan was born in England, but grew up in Bangor, and represented Northern Ireland at schoolboy level. However, IFA regulation at the time meant only players born on Northern Irish soil could represent the national team. Therefore Kerneghan, relying on his grandmother’s Irish citizenship, opted to play international football for the Republic instead. This made him an easy target for the Windsor Park crowd, who welcomed him with shouts of ‘Lundy’ (or traitor, in reference to a Colonel Lundy in 1689 who wanted to surrender Derry to Catholic Jacobite forces).

Jack Charlton recalled that he had “never seen a more hostile atmosphere.” Republic midfielder Alan McLoughlin still vividly remembers the fervent abuse he witnessed from the substitutes bench:

”I could hear it and feel it right behind me. You didn’t dare look around and make eye contact. The venom in their eyes shocked me.”

Events on the pitch added fuel to the fire. Jimmy Quinn’s 73rd-minute goal seemed to have sunk the Republic and sent Windsor Park into a frenzy. Just five minutes later, however, McLoughlin came off the bench to equalise. The result ended 1-1, securing the Republic’s place in the finals. It was an extraordinary end to one of the most heated encounters in the history of Irish football.

Building bridges?

Many will agree that progress has been made politically. The Good Friday Agreement ushered in nearly two decades of peace, and thankfully the dark days of The Troubles seem to have departed. However, football is inherently tribal, and old hostilities die hard.

In 2002, Northern Ireland’s Neil Lennon received abuse and death threats from a section of his own fans. A Catholic, a Celtic player, and a supporter of a United Ireland team, Lennon became a natural antagonist for some of Northern Ireland’s more hardcore supporters.

This being said it does seem that some of the most unsavoury elements of the rivalry have diminished in recent years. Northern Ireland and Ireland have met each other in friendly matches since, with a less poisonous reception.

Furthermore, the IFA has rolled out initiatives to reduce sectarianism in football. A United Ireland team still seems a long way off, but the relationship has become more cordial.

Sathesh Alagappan is a History graduate from the University of Southampton, where he primarily studied 20th century history. He has also worked as a Researcher at Manchester United Football Club.