Mrs. Brophy’s Late Husband

Shortly before James Brophy was killed in Dublin during Ireland’s War of Independence, an Irish immigrant of the same name disappeared from his family in New York City. The coincidence offers a glimpse of early 20th century Irish lives on both sides of the Atlantic, when handwritten letters crossed at sea, and personal identification was more vague than today.

By MARK HOLAN

About half seven in the evening of 12 February 1921, a British Army lorry packed with soldiers and accompanied by two armoured cars and a tender rumbled north from the Dun Laoghaire waterfront. The vehicles motored swiftly through Monkstown, Blackrock and Booterstown. Suddenly, near the Merrion Gates, 10 IRA men ambushed the convoy.[1]

There were “three terrific explosions resembling bomb detonations,” the Irish Independent reported, followed by “heavy firing” from both sides. The skirmish ended in less than five minutes without any combatant casualties. There were two civilian fatalities: John J. Healy of Blackrock, and James Brophy of Merrion.[2]

Healy was a dairy proprietor, insurance agent and former member of the Blackrock Council. He got caught in the crossfire near the Elm Park and fell dead on the footpath. Brophy worked as a fitter or watchman for the Dublin United Tramway Company. A stray bullet penetrated his home at 244 Langford Terrace, Merrion Road, while he was lying in bed.

Though both men lived in south Dublin, it is impossible to know whether they ever met. Two months after being shot, however, Healy and Brophy were entered on consecutive lines of the civil death register.[3] The cause of death for each was given as “shock and haemorrhage following gunshot wounds,” and the euphemism “misadventure,” which hardly connected their sudden passing to the war.

War-related civilian deaths in Ireland during the 1919-1921 fight for independence are tricky to catalogue. According to the figures of the Dead of the Irish Revolution project, published in Terror in Ireland, at least 898 civilians lost their lives, the majority in the first six months of 1921. Those figures probably miss fright-induced heart attacks and other indirect deaths in the war zones.

An IRA ambush on a British military patrol in south Dublin in February 1921 killed two civilians, James Brophy and John Healy

About 240 civilians, like Healy and Brophy were killed in the crossfire of armed engagements, with the responsibility difficult to attribute definitely to either side.[4]

Their deaths, like the skirmish itself, did not influence the arc of Ireland’s struggle for independence. As it turned out, however, Brophy’s death created a ripple across the Atlantic, one that shows how the waves of war wash over ordinary lives.

James Brophy, New York

In February 1921, wire service accounts of the IRA ambush at Merrion Gates appeared in numerous American newspapers, with Healy and Brophy identified as victims.[5] The story would have been widely read by Irish immigrants following the war back home. It particularly caught the attention of one living in a New York City tenement: Anna Brophy.

In New York, another James Brophy went missing in 1917, his wife claimed he was the man killed in Dublin 1921.

Anna married James Brophy around 1886, when each was about 25, six years after they emigrated from Ireland.[6] They were among more than 80,000 Irish who sailed to America in 1880, up from 30,000 in 1879 as the Land War began.[7] Other records date their crossing between 1879 and 1883, still within that period of agrarian unrest known as the ‘Land War’. The couple settled in Newport City, Rhode Island, and produced 10 children, nine who survived to later years. James Brophy worked as a blacksmith.[8]

By 1910, the family relocated to Governor’s Island, New York, a small military base at the confluence of the Hudson and East Rivers at the tip of Manhattan.[9] James continued working as a blacksmith, now employed by the U.S. government. His sons Patrick, 21, and John, 20, also were employed at the military base, as a gardener and plumber, respectively.

It was noisy and dusty as U.S. government engineers supervised the deposit of more than 4.7 million cubic yards of rock and dirt from the Lexington Avenue subway excavation and New York Harbor dredge to expand Governor’s Island.

The work had begun eight years earlier, and by 1912 the size of island more than doubled to 172 acres. When America entered the Great War in 1917, the new acreage quickly filled with hastily erected warehouses as the base became a major troop embarkation and shipping point for the war.[10]

James Brophy disappeared from his family about this time. Perhaps he went back to Rhode Island. Maybe he stowed away aboard a war-bound ship. In June 1917, his sons John and Joseph each registered for the U.S. military with a home address of 352 W. 52nd St. in New York’s notorious Hell’s Kitchen.[11]

Next to the registration question of whether a parent, spouse, sibling or child was “solely dependent on you for support,” Joseph wrote, “Mother.” He repeated the reference to Anna on another line to ask for a draft exemption. His brother answered “No” to both questions.

Over the next few years Anna Brophy headed the household at 352 W. 52nd St., joined by several of her children, but not her husband. She still considered herself a married woman, not a widow.[12] [13]

More than 30 other people occupied the eight-story brick and stone loft building, including other Irish immigrants and people from Scotland, England and Germany, as well as American-born residents from New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maine and Rhode Island.[14]

James Brophy, Dublin

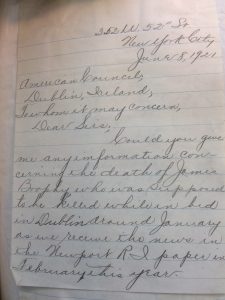

On 6 June 1921, Anna Brophy sent a handwritten letter from this address to the Dublin office of the U.S. Consulate in Ireland.[15] She asked for “any information” about the death of James Brophy “who was supposed to be killed while in bed in Dublin.”

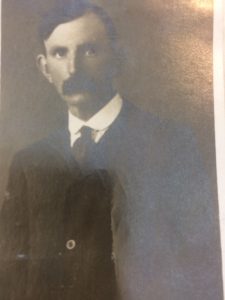

Anna wrote that she learned of it from a Newport, Rhode Island, newspaper story. Today, a black and white photo of a middle-aged man with a thick moustache, presumably James Brophy, is attached to her letter, which is held with all the consulates’ correspondence and other paperwork at the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, on the eastern edge of Washington, D.C.

Anna Brophy began a campaign to prove that her husband had died in the ambush at Merrion Gates in Dublin.

From the late 18th century, the U.S. government maintained consulates in Belfast, Cork, Dublin and Derry, and periodically operated smaller offices in Athlone, Ballymena, Galway, Limerick, Newry, Waterford and Wexford. Much of the work was commercially focused, but the diplomats also were involved in the major political and social issues of the day, including the Irish Famine, the American Civil War and ongoing waves of immigration.[16]

Consulate officials also handled more routine matters, including notes and letters from America asking about missing people and the dead; for emergency passport applications; and inquiries about estates and pensions.

F.T.F. Dumont, the American consul, promptly sent a typed reply to Anna that he referred her request to the Dublin Metropolitan Police. The same day, he wrote to Lt. Col. W. Edgeworth Johnstone, the DMP’s chief commissioner, asking for details about Brophy’s death. Dumont sent a second letter a month later when Johnstone’s office apparently failed to answer the initial outreach.

On 25 July 1921, the DMP replied to Dumont that about 7:40 p.m. on 12 February “as a party of military were motoring along Merrion Road in the vicinity of the residence of James Brophy, they were ambushed by Sinn Feiners, who threw bombs and fired a number of shots at them, at which they replied with their rifles. While this was going on a bullet passed through Mr. Brophy’s bedroom window wounding him in the breast as he lay in bed.”

Dumont mailed a copy of the DMP report to Anna in New York. She focused on the report’s mention of Brophy’s widow and her Dublin address. Within days, Anna wrote to the woman in Ireland, according to her 5 October 1921 letter to the consulate.

“As yet have not received an answer from her,” the New York Mrs. Brophy wrote of the Dublin Mrs. Brophy. Anna added she was “quite sure” that the Merrion victim “is my husband and that he had been living with her as man and wife.” She also acknowledged that she deceived the other woman by writing “under one of my daughter’s name saying I was his sister, thinking if I done that she would write quicker than if I said I was his wife.”

An insurance policy on James Brophy’s life motivated Anna. “I can’t afford to keep paying for it,” she explained to the consulate, if her husband died in the Irish war. Her letter said she included a photo of James Brophy and suggested “maybe it would help you if you were to take it to his supposed widow” or to the hospital where he died. “Perhaps they found citizen papers and also government papers as he was a post blacksmith and horseshoer.”

James Brophy’s one-time employment with the U.S. government may have helped Anna obtain the policy. Life insurance sales began to soar in this period, fueled by the booming economy and rise of personal income. The sales also reflected the changing demographics of America’s growing urbanization, increased life expectancy and decreased reliance on extended family as a source of income and support.[17]

Anna’s concern about the policy was sufficient for the consulate’s office to send a second letter to the DMP, which asked for more information about the man killed in bed. On 8 November 1921, the DMP replied that the victim was a native of Killadooley, Ballybrophy, Queen’s County (Laois), “the son of a small farmer there.” (The county had the heaviest concentration of the Brophy surname in mid-19th century Ireland.[18])

James Brophy moved to Dublin about 1896 and was employed by Messrs. Adam Miller & Co. Wine Merchants, Thomas Street, the DMP wrote. He later worked at the Blind Asylum, Merrion, and for the Dublin United Tramway Company. “He was never a horse-shoer or blacksmith,” Dublin police said.

At least 20 men named James Brophy lived in County Dublin in the early 20th century.[19] Six of them were near an age to make them possibilities for the man killed in the 1921 ambush. The DMP letter enclosed a marriage record showing that on 29 May 1918, James Brophy, “labourer,” and the former Sarah Moloney, “spinster,” married at the Catholic church in Booterstown. The couple soon had a son.

On the evening of 12 February 1921, James Brophy retired to bed 30 minutes before the explosions, cradling the toddler in his arms to comfort the boy to sleep.[20] Sarah Brophy later said she thought the burst was the backfire of a car. As she was about to look outside, her husband exclaimed, “I am shot.” A bullet hit him in the torso, but the boy escaped injury.

James Brophy of Dublin was hit by a stray bullet while holding his infant son in bed.

Sarah discovered the child “crying bitterly” with his arms around his wounded father’s neck.[21] A Booterstown priest administered the last rites in the home. Then, an ambulance rushed Brophy to the Royal Dublin Hospital, about two miles away, where he soon died.

Two days later, the Independent published a photo feature headlined “Military Activity in Dublin.” One of the page 3 images shows a man holding a small boy in his arms. The caption reads: “Denis Brophy, the 4-year-old son of Mr. James Brophy, who was mortally wounded during the ambush at Merrion road. The child was in bed with his father when the unfortunate man was shot.”

Nine months later, the DMP’s November 1921 report concluded, “There is no record of any other man named Brophy being shot at Dublin and as far as can be ascertained he was not a bigamist.” A photo of the victim also was included, the reply said, though today only the marriage record remains in this part of the consulate’s archived file.

Soon after her husband’s death, Sarah Brophy filed a compensation claim on his weekly salary of £3, 4s, which appears to have been granted.[22]

Even so, it must have been difficult to raise her son as the new Irish Free State lurched from war against Britain to a bitter civil war and its uncertain economic aftermath. In the 1920s, widows and children remained in the care of an outdated and stigmatising home assistance program with low payments, even though such families were considered the most deserving of the poor.[23]

Still fighting

The U.S. consulate sent a copy of the DMP’s November 1921 report to Anna Brophy. “With this information it would appear that this is not the person whom you suppose to be your husband,” the letter said. If Anna wished to pursue the matter further, she should provided details about whether her husband was a naturalized American citizen, the dates he immigrated to America and returned to Ireland, “and the names of his nearest relatives with their addresses.”

Both the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the American Consulate in Ireland confirmed that James Brophy who was killed in 1921 was not Anna’s missing husband.

A simpler detail might have resolved the confusion, one never raised by the consulate, the DMP, or Anna: James Brophy’s age. American records indicate the man who disappeared in New York was born about 1863, or 58 at the time of the Merrion ambush. The man killed in bed was 37, according to the civil death register, up to 45 in some news accounts.

Anna refused to accept the consulate’s conclusion. The life insurance policy was still unresolved, and she remained convinced the victim was her husband. This wasn’t the first time he had disappeared. “He has often done this before,” Anna wrote in a 17 July 1923 letter, which also referenced 1922 correspondence.

She apparently mailed a second letter to Sarah Brophy in Dublin, who “never answered and I think she is guilty,” Anna wrote. She demanded the consulate return her photo of James Brophy, and accused the diplomatic office of intentionally placing the article about the Merrion attack in the Newport newspaper. “Please look into this matter again as I think this is my husband [who has] been missing for many years,” she concluded.

It is impossible to know if Anna Brophy was a calculating insurance fraudster or simply maddened by the long and frequent disappearances of her husband.

Shortly after he received Anna’s July 1923 letter, U.S. Vice Consul Loy Henderson replied that the 1921 shooting victim “could not be the same James Brophy whom you married,” as proved to the satisfaction of police. For the record, he added: “This office is not accustomed to furnish news items to any paper and certainly did not communicate with any newspaper concerning the death of James Brophy.”

Anna persisted. “You never seem to tell me the right answer,” she complained in a 5 March 1924 letter. She asked once again for the consulate to return of her photo of James Brophy. “If you do not give me some information, my son will go to Washington, D.C. and see if the authorities can look it up for me,” she threatened.

The final letter in the archive file is dated 19 March 1924, nearly three years after Anna’s initial outreach. Consul Charles M. Hathaway Jr. replied to Anna that he was returning her photograph. “There seems to be no reason to identify the James Brophy who died in Dublin on February 12, 1921, with your missing husband,” he concluded, referencing earlier correspondence.

It is impossible to know if Anna Brophy was a calculating insurance fraudster or simply maddened by the long and frequent disappearances of her husband. Whether she ever collected any insurance money, or how much, remains a mystery. The fate of James Brophy the blacksmith is just as uncertain. A positive match among death and burial records of many men of the same name was not immediately located.

By 1925, however, it appears Anna finally found and accepted proof of his death. That year, the New York City city directory added two abbreviations between Anna’s name and her 352 W. 52nd St. address, a designation that had not appeared in earlier editions: “wid Jas,” widow of James Brophy.[24]

Mark Holan can be reached at [email protected]. He blogs at www.markholan.org. © 2016 by Mark Holan

References

[1] Bureau of Military History, Statement of Patrick J. Brennan, page 16.

[2] The Irish Independent, 14 February 1921, page 5.

[3] Civil death record via IrishGenealogy.ie. Group Registration ID 3391765, Dublin South. LINK

[4] Eunan O’Halpin, Counting Terror, in Terror in Ireland edited by David Fitzpatrick, Lilliput 2012, p. 153-154.

[5] The New York Herald, 14 February 1921, page 3, and other newspapers via Library of Congress/Chronicling America.

[6] 1900 U.S. Census, Newport Ward 2, Newport, Rhode Island; Roll: 1505; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 0215; FHL microfilm: 1241505

[7] Whelan, Bernadette, “American Government in Ireland, 1790-1913, A History of the U.S. Consular Service.” Manchester University Press, 2010, pages 220-221.

[8] 1900 Census, and Newport City, R.I., city directories, 1887 to 1892.

[9] 1910 U.S. Census, Manhattan Ward 1, New York, New York; Roll: T624_1004; Page: 1A; Enumeration District: 0002; FHL microfilm: 1375017

[10] New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (See PDF), and Govisland.com.

[11] U.S. World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, John and Joseph Brophy, via FamilySearch.

[12] 1918 New York City City Directory, page 404, via Heritage Quest.

[13] 1920 U.S. Census, New York Co., Manhattan Borough (ED’s 429-461) [NARA T625 roll 1194]

[14] 1920 U.S. Census, and Office for Metropolitan History, “Manhattan NB Database 1900-1986.

[15] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, Maryland, USA. U.S. Consulate in Ireland records, 1921-1924. Files reviewed by author on 1 November 2016.

[16] Whelan, “American Government in Ireland,” page xiv.

[17] The Center for Insurance Policy & Research, “State of the Life Insurance Industry,” 2013 report, pages 2 and 10 (See PDF).

[18] SWilson.info Surname Distribution.

[19] 1901 and 1911 Irish census, via The National Archives of Ireland.

[20] Freeman’s Journal, 14 February 1921, pages 5 & 6.

[21] The Irish Independent, 14 February 1921, page 5.

[22] The Irish Times, 21 April 1921, page 5.

[23] Lucey, Donnacha Seán, “The End of the Irish Poor Law? Welfare and healthcare reform in revolutionary and independent Ireland.” Manchester University Press, 2015, page 120.

[24] 1925 New York City City Directory, page 484, accessed through Heritage Quest.