‘Cowardly, Cunning and Contemptible’ – The British campaign in Dublin, 1919-1921.

The British counter-insurgency campaign in Dublin 1919-1921. By John Dorney.

A British Army private, J.P Swindlehurst, stationed in Dublin from January to February 1921 recorded in his diary;

‘Dublin seems to be a rotten place to be…people hurry along the streets, armoured cars dash up and down, bristling with machine guns’… The men who style themselves as Black and Tans walk about like miniature arsenals… They dash about in cars with wire netting covering at all hours of the day bent on some raid reprisal or capture of some Sinn Feiners’… One can sense the undercurrent of alarm and anxiety in the faces of the passers-by’.[1]

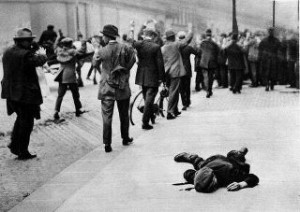

A British soldier in Dublin in 1920 and 1921 had an unenviable task. Tasked with policing a mostly hostile city, faced at any moment with possible attack from unseen adversaries, scanning the faces of passers-by for suspects, searching disgruntled civilians for arms, keeping watch on the roof tops and windows for grenade throwers and the street corners for IRA gun men.

The campaign in Dublin was something new for the British Army, an urban guerrilla insurgency.

The British Army had conducted innumerable counter insurgency campaigns across the Empire throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

And the rural counter-guerrilla operations in Ireland during the War of Independence, with their ‘drives’ across countryside by motorised and cavalry columns, establishment of small fortified posts across the countryside and mobile ‘flying columns’, could certainly have taken place on the North West frontier of India, against the Boers in South Africa or other far flung parts.

The conflict in Dublin however, was something different and new. Something that has in the 21st century since become much more common for occupying armies; an urban guerrilla insurgency.

Here the insurgents did not hide in mountains or remote areas, but hid in plain sight among the civilian population. Combat was fleeting and the British forces’ overwhelming firepower could hardly ever be brought to bear, in 1919-1921, as it had been in Dublin in the Rising of 1916.

Even stranger for the Army was the fact that for decades the British Army had been familiar, and even welcome to some, presence in Dublin city. It’s transformation into an army of occupation as the question of Irish independence turned into an armed conflict, must have come as a jarring shock to many British personnel.

The British Army itself was not the only counter-insurgency force at work in the city. Civil order and intelligence was supposed to be provided by the Dublin Metropolitan Police, but they, unarmed, opted out of the war in late 1920, entering a live-and-let- live understanding with the IRA.

A much more potent force were the companies of Auxiliaries stationed in the city, who made up the rapid response force for most raids and ambushes, and units of the Royal Irish Constabulary, beefed up with ‘Black and Tan’ ex-soldier recruits, who were deployed into Dublin during the conflict.

While the British Army, like every other actor in the conflict, became brutalised by the cycle of attack and retaliation, it was the paramilitary police forces who became the most feared and hated by the Dublin public.

A vicious cycle

The IRA campaign in Dublin began with assassinations of selected police detectives by Michael Collins’s Squad in 1919 and early 1920 and fulltime IRA urban guerrilla units were not formed until late 1920 in the city.

It was the roughly twelve months between the summer of 1920 and the truce of 1921 that saw the vast majority of violence in Dublin during the war.

The conflict, in Dublin as elsewhere, had a gathering pace of brutalisation. Initially British troops were generally not attacked when unarmed and off-duty, the object being to take their weapons rather than their lives.

Many soldiers were disarmed but not injured by IRA guerrillas in Dublin up to mid-1920 and even later. [6]

Similarly in the early stages of the conflict the British conduct could be moderated by public opinion. In March 1920 when the IRA prisoners in Mountjoy Gaol went on hunger strike, provoking mass protests and a general strike, the British authorities gave in and released them, much to the disgust of the military.

They reported of the mass release of the hunger strikers; ‘The Military and police secret services personnel were virtually driven off the streets owing to those whom they had arrested now being free and in many cases able to identify our agents. This necessitated a temporary cessation of our secret service activities’.[7]

By late 1920, both sides were carrying out ruthless assassinations and killing of prisoners.

This restraint on both sides did not outlast the IRA offensive of the summer of 1920 and the British counter-offensive of that autumn, however, in which paramilitary police recruits the ‘Black and Tans and especially the Auxiliary Division, a specially raised counter-insurgency force, was deployed.

In Dublin the first company of Auxiliaries, F Company, were based and in Dublin Castle and they were later joined two further Companies, I and J, based in Beggars Bush Barracks. A fourth company Q, was ultimately formed to patrol the docks and shipping. [8]

Emergency legislation known as the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act enacted in June 1920 allowed for executions and internment without trial of republican suspects.

To replace the defunct DMP Detective Division, the British brought in a squad of Irish RIC detectives led by Captain Igoe and known to the IRA in Dublin as the ‘Igoe gang’. These men patrolled Dublin City in plain clothes, attempting to spot known IRA members both from the city and outside. Commanded at first by British military and then police and secret service intelligence, they were given the responsibility for intelligence gathering in Dublin.

Black and Tans and Bloody Sunday

It was the paramilitary police, with their indiscipline and hostility to the general population, who did most to turn the civilian population against the Crown forces. Dubliners, in an oral history recorded decades later, often recalled the casual brutality of the Black and Tans in the 1920s.

Nellie Cassidy, who grew up in a tenement on City Quay recalled;

‘during the war it was dangerous, ‘cause the bullets was flying everywhere. And you’d never be sure when the Black and Tans would arrive. I was only seven at the time but I remember it. They used to frighten the people terrible. They came into everybody’s house and if there was shutters on your window they’d tear the shutters asunder to see if there was documents or anything behind them….There was two chaps belonged to the IRA that lived in the tenement house with us’.[9]

It was not long after the arrival of the Black and Tans that the insurgency in Dublin deepened both in intensity and bitterness.

Ordinary Dubliners hated and feared the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries much more than the regular British troops.

Both sides blamed the other for what one author has called ‘the turn to terrorism’, in Dublin.

The Squad, the IRA Intelligence unit run by Michael Collins, certainly began the assassination of detectives and informers in 1919, but it seems clear that by late 1920 the state forces had also resorted to a policy of lethal reprisals. In the month of October 1920 alone, the Republican roll of honour records 4 Volunteers ‘murdered by British forces’ in Dublin after being taken prisoner.[10]

In November 1920, Michael Collins, the IRA Director of Intelligence, hit back at British military intelligence, on what has become known as Bloody Sunday, assassinating 14 men, of whom at least eight were British military intelligence officers. The men were tracked down by a number of means and mostly shot in their beds.

The Crown forces’ revenge that day more than offset any negative publicity Collins’ ruthless operation might have generated.

That afternoon, Crown forces, both police and military, raided Croke Park, the Gaelic Athletic Association grounds, for suspects and once inside opened fire, killing 14 civilians. For good measure, three Republican prisoners, Dublin Brigade commander Dick McKee, his subordinate Peadar Clancy and a civilian friend of theirs, Conor Clune were summarily executed in Dublin Castle.[11]

It was the paramilitary police, with their aggression and lack of discipline rather than the regular British military who carried out both of the reprisals. At Croke Park, it was, the police commander, Crozier reported, ‘the Black and Tans [who] opened fire into the crowd without any provocation whatsoever’. [12] Though he maintained that his own Auxiliaries had not fired. At Dublin Castle, however it was the resident Auxiliary ‘F Company’ who murdered the three prisoners. [13]

That Crozier, the supposed commander of the Auxiliaries, resigned,, not over the Croke Park shootings, but over a subsequent incident when his men looted Trim, but were reinstated, tells us how little they were under effective discipline.

Many Dubliners made a distinction between the regular British military, who were ‘decent’ and ‘gentlemen’ and the ‘Tans’, who were, to their minds, ‘criminals’ and ‘riff raff’.

Billy Dunleavy of Foley Street, a Sinn Fein supporter, recalled of the Black and Tans;

‘People hated them. The British soldiers were different altogether, they’d go out there and maybe be talking with people. But the Black and Tans was all a gang of criminals, all gangsters out of the prisons. All riff raff out of the prisons. Always ten or twelve of them together in armoured cars. You couldn’t get out in the night ‘cause they’d come along and give you a hiding. Broke windows, shot at people, robbed ‘kip houses’ [brothels]’. [14]

Frank Wearen, a 14 year old messenger boy who joined the IRA in 1920 similarly thought;

‘The British soldiers were gentlemen because they were the sons of good English people, but the Black and Tans were all recruited from long terms prisons in England…If you were walking along the path and you sort of looked at them they’d give you a boxing …for nothing! Just for looking! [15]

Regular British troops were indeed generally better behaved both towards civilians and towards prisoners than the paramilitary police. We may suggest two reasons for this. The first is that the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries were for many months outside any recognised chain of command and therefore free to whatever they wanted without fear of sanction. The British military, on the other hand, were at all times under military discipline and subject to punishment for transgressing it.

Secondly, while most of the ‘Tans’ and ‘Auxies’ were hardened veterans of the First World War, most British troops stationed in Dublin in 1920 and 1921 were raw recruits who had not served in the European war (‘many of whom had hardly fired a rifle’ the official history of the Dublin command reported) and had not been through years of brutalisation in the trenches. [16]

Discipline within British forces in Dublin as a whole improved somewhat in late 1920 as the Auxiliary companies were put under military command. However reprisals continued in the new year. Three Auxiliaries, for instance were arrested, though later acquitted, for the summary execution of two IRA men captured in Drumcondra in February 1921.[17]

As the killing went on, however, regular British Army troops began to also mete out their own ‘rough justice’ on the streets of Dublin in revenge for the death of their comrades at the hands of the IRA . James Cahill, a member of The IRA Dublin Brigade’s Active Service Unit, described a summary execution of a captured IRA Volunteer Harry Kelly, who was beaten to death with rifle butts by British troops after he had shot a soldier in late 1920.[18]

Of the 54 IRA men killed in Dublin between 1919 and 1921, only 16 were counted as ‘killed in action’ by the guerrillas and eight were formally executed, indicating that up to 30 were summarily executed.[19]

Civilians also suffered, both shot in the crossfire of street ambushes and on occasion also, by nervous or vindictive troops.

Official executions of captured IRA men began with the celebrated case of 18 year old medical student Kevin Barry on November 1st, who was hanged for his part in an arms raid that had left two British soldiers dead.

The next hangings came in the new year. A botched ambush in the northern suburb of Drumcondra by the IRA Active Service Unit in January 1921 led to the executions of the 6 prisoners on March 14 1921 and a further Volunteer, Thomas Traynor, captured in the Brunswick Street ambush was hanged in April of that year. Finally, in June two more Volunteers from the Tipperary Brigade were hanged in Mountjoy Gaol.[20]

Counter-Insurgency

If part of the story of the War of Independence in Dublin, as in other badly affected localities such as Cork, was of a cycle of attack and reprisal, the other part was of a tactical game of wits in which the Crown forces attempted to prevent guerrilla attacks and to track down and destroy the guerrillas themselves. So it was in Dublin.

From late 1920 onwards, the IRA formed a fulltime Active Service Unit (ASU) in the city, over about 100 men divided into four sections, whose job it was to carry out at least three gun or bomb attacks a day. Later, in early 1921, the regular ‘companies’ were ordered also to ‘patrol’ their allocated area and fire on any police or troops they encountered.

Particularly dangerous ambush spots for British forces were the quays along the river Liffey and the Aungier Street- Wexford Street thoroughfare, which was nicknamed the ‘Dardanelles’.

The Crown forces were therefore placed in a position in which most of their time was spent patrolling streets for anonymous guerrillas, or tedious manning of checkpoints, checking civilians for weapons. None of which really succeeded either in suppressing small scale IRA attacks or breaking up IRA units or cells.

The British Army in Dublin was forced to improvise rough and ready methods to deal with the new phenomenon of an urban guerrilla war.

Nevertheless, over the following months the Army worked out several rough and ready methods of fighting the clandestine war in Dublin. After a number of deadly ambushes in the Dublin streets, notably one on Wexford Street in which four soldiers died in a grenade attack, new instructions were given to troops going on foot patrols. Outposts were to be mounted on rooftops overlooking the street, a ‘parallel patrol’ was to comb the adjacent streets for ambushers.[21]

A nightly curfew was also enforced, at first from midnight to 5 am and then, after Bloody Sunday, from 10 pm to 5am and ultimately from 8pm to 5 am. Troops were instructed that, ‘Unauthorised persons found in the streets during curfew hours are liable to arrest but are not liable to be shot unless seen to be carrying firearms’. The longer the war went on, the more restraint, including towards civilians, was cast aside. In May 1921, new orders were issued that, ‘civilians were warned to halt if called upon to do so, otherwise they were liable to be shot’.[22]

Predictably this did indeed lead to the shooting of civilians who ‘failed to halt’. Michael Ryan, aged 23, for instance, was shot in the stomach on Marlborough Street in the north inner city when he did not respond to a challenge in March 1921. Daniel Duffy, who worked in the Guinness Brewery was fatally shot when he encountered a military road block on Clanbrassil Street on his way home during curfew hours in July of that year. [23]

On two occasions, whole blocks of the city, populated by thousands of people, were cordoned off, with no civilians allowed in or out until the area was searched by troops or police. The area around the Four Courts was sealed off and searched from 15-17 January 1921 and the Mountjoy Square area over 18-19 February. Doors were, if necessary, broken down using tanks as battering rams, rooms were ransacked, suspects taken away for questioning.

The results however were ‘indifferent’. The British military reported; ‘Dublin is honeycombed with underground cellars and passages’ allowing suspects to escape. In future, searches were restricted to 2-3 hours.[24]

Aerial reconnaissance was also used to flush out dug outs and arms dumps in the nearby Dublin Mountains, but was of little use in the city itself except at time to try to intimidate demonstrations by flying low over protesting crowds.

On two occasions, whole city blocks were cordoned off for days and subjected to intensive searches.

British armoured vehicles were ‘up-armoured’, i.e. fitted with armour plates to withstand bombs and bullets. Tanks and armoured cars were also used as escorts to troops lorries.

IRA man James Cahill recalled, ‘the introduction by the British of armour plating and steep sloping and close wire mesh on their vehicles rendered our six second timed grenades ineffective as it was impossible to get them into the vehicles’. The guerrillas were forced to experiment with even risker 2 second fuses.[25]

Hostages were also used by Crown forces to deter attacks on convoys, in some cases prisoners were tied to military vehicles with a notice pinned on them reading ‘bomb us now’.

‘Law and order was maintained in no uncertain fashion’

By the summer of 1921 and the Truce of July 11, the British thought they were getting on top of the IRA in Dublin; many guerrillas had been arrested and over 1,400 interned.

The problem was though, that while British intelligence, which had been transferred from the military to the police command in early 1921, had been able to amass a substantial amount of information from interrogation of prisoners, they had failed to effectively infiltrate the Republican fighting organisation and therefore unable to ‘roll it up’ and capture its leadership.

IRA Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy claimed that the Dublin IRA had, ‘pinned 1/6th of English armed forces in the city without too much effort.[2] The British forces, commanded by Major General Boyd, a veteran of the First World War, where had served in the Army General Staff, thought differently.

The British Army described the Dublin IRA as ‘cowardly, cunning and contemptible’.

For them, ‘in spite of determined opposition by a large number of men, backed up by sympathetic or fearful populace, law and order was maintained in no uncertain fashion throughout.’ It was only, ‘legal technicalities and political considerations’ which had prevented them from completely defeating the Dublin IRA whom they described as, ‘cowardly, cunning and contemptible’. [3]

Where did the truth lie?

There were over 7,700 British troops stationed in the city and up to 1,600 armed police, including four companies of Auxiliaries (F,I, J and Q Companies) and 1,200 men from the Royal Irish Constabulary, many of whom were wartime ‘Black and Tan’ recruits. This excludes the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), who were mostly unarmed.[4]

By contrast, the Dublin IRA Brigade had a paper membership of 2,000 men but only about 200 fulltime operatives and several hundred more part time fighters.[5]

In light of this, the fact that the IRA was able to maintain armed operations in Dublin until the Truce and thus, from their point of view, keep political pressure on the British to negotiate with their leaders, was a significant achievement.

The British Army’s official report of the Dublin command on the ‘Irish Rebellion’ argued that by July ‘the rebels had again begun to realise how hopeless was force. They had been driven to resort from one method to another and in the final stages to adopt the least dangerous methods to themselves’. Nevertheless, the same report concluded that ‘we were compelled to remain on the defensive… [owing to] congestion of prisoners and later through lack of troops’.[26]

The IRA however were in fact far from finished in Dublin by that date. There was no shortage of new recruits and the pace of attacks slackened only a little, even after the disaster of the Customs House attack of May 1921 in which over 100 Volunteers were captured. The Dublin Brigade recorded 67 attacks in the city in April 1921, 103 in May and 92 in June.[27] Ammunition was certainly a problem, in some cases IRA ‘factories’ in the city were put to work at the risky task of converting .303 rifle ammunition into .45 revolver bullets.[28]

The British Army Dublin command believed that they had the IRA on the ropes by July 1921, but in fact the guerrillas were far from finished by the time of the truce.

But like the Crown forces, the IRA was also adapting. The first batches of Thompson submachine guns had arrived in the city and were used in several ambushes in Dublin in June 1921. There was also a turn towards avoiding combat altogether and destroying British war infrastructure. A raid on the Military transport depot in June 1921 destroyed 40 vehicles including five new British armoured cars, without any shooting taking place.[29]

Violence abruptly ceased in mid-July however, as the British government and the Sinn Fein leaders agreed that a Truce, whereby both sides would cease offensive actions, which would come into force on July 11th 1921. Dublin was reported to be ‘calm’ rather than ecstatic on the day of the Truce, but everyone noticed immediately, ‘the complete disappearance from the streets of military and police lorries and armoured cars’.[30]

The IRA used the Truce period to rearm and to train its Volunteers, while the British garrison could only watch them nervously.

A British Army report in October 1921 on the possibility of the resumption of hostilities noted that IRA, ‘in a desperate situation before the Truce’, with’ their ASUs and columns being chased and harried from pillar to post, defeated and broken up’, was now ‘a more formidable organisation’. They reported that the IRA was recruiting ex-soldiers to help with training was now better armed, including with the Thompson sub machine gun and also had far more rifles with which to carry out sniping attacks.[31]

Had hostilities broken out again in Dublin, if negotiations in London had broken down, there is no doubt they would have been of a higher and more lethal intensity than they were before the Truce.

Casualties

Casualties from nearly three years of political violence in Dublin were well under what they had been in just 6 days of urban warfare in the Rising of 1916 when around 500 people lost their lives. Material destruction had also been much less. On the other hand, almost all of the deaths had occurred in a nine month period from October 1920 to July 1921. Particularly from November 1920 onwards, Dublin had been a fearful place to live, with unexpected irruptions of shooting in the streets, the night time appearance of dumped bodies, a nightly curfew and a huge and intimidating military and police presence.

Some 300 people had died violently in Dublin by July 11th 1921 and hundreds more had been wounded.[32]

The IRA counted 54 of their Volunteers killed in Dublin[33] and according to British figures, another 70 guerrillas at least were wounded in action and over 1,400 arrested and imprisoned.[34]

The British military admitted their losses in the city as 25 soldiers killed and 68 wounded, but a careful modern count found 35 killed by the IRA in the city with another 42 non-combat deaths due to firearms or other accidents, 3 murders of fellow soldiers and 12 suicides. [35]

Some 40 policemen were killed in Dublin by IRA action. This included 8 DMP officers, mostly detectives killed by the Squad, and in addition, 11 Auxiliaries and 22 RIC or Black and Tans officers also lost their lives at the IRA’s hands in Dublin. In total, therefore about 75 Crown forces were killed in action in Dublin in 1919-21, a number that rises to about 110 once accidental deaths are included.[36]

If between them, combatant deaths amount to about 160-180, then around 140-120 civilians must also have died, subtracting the combatant figure from O’Halpin’s total of 300 deaths.

Conclusion

The War of Independence in Dublin cannot be said to have had any military conclusion. Neither side ‘won’ in military terms. The British military might have claimed, as they did in their official report on the campaign that,

‘The IRA as an army had ceased to exist and were reduced to bands of ruffians who sooner or later were bound to fall into our hands’. They bemoaned that the political will was not present to allow them to finish off the insurrection; ‘Drastic shooting…was all that was required to end the matter for the time being ’.[37]

The British military bemoaned that they had not been allowed to carry out ‘drastic shooting’ to end the insurgency.

What the military failed to understand, however, as their political superiors did, was that ‘drastic shooting’ only alienated the Irish population further and made more difficult the task of extricating Britain from the south of Ireland on its own terms.

While the British Army in Dublin did manage to adapt to face an urban insurgency in Dublin, they did not crush it. Ireland’s capitals’ fate would be decided, in the end, by negotiations and not by bullets.

References

[1] Cited in William Sheehan, British Voices of the Irish War of Independence, Collins Books, 2007, p13-17

[2] Richard Mulcahy Papers UCD, P7/A/47

[3] William Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, The British Battle for Dublin 1919-1921, Collins Press, 2007, p79-80. Sheehan’s book is a reprint of the British Army Dublin command’s official report of the campaign and is cited extensively in this article.

[4] William Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p 125. James Durney, When Aungier Street became the Dardanelles, The Irish Sword, Summer 2012, Vol XXVII, p245

[5] See John Dorney, the IRA Dublin Brigade 1919-1921 https://www.theirishstory.com/2016/08/31/the-dublin-brigade-ira-1917-1921/

[6] See for instance the recollections of Pte Swindlehurst, in William Sheehan, British Voices from the Irish War of Independence 1919-21 p11-13 who was held up but not harmed when cornered unarmed on O’Connell Street in January 1921.

[7] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p15

[8] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin pp, 37, 50

[9] Kevin C. Kearns, Dublin Tenement Life an Oral History, Gill& MacMillan, Dublin 1996, p87

[10] The Last Post p105-106, the ‘turn to terrorism’ phrase is Peter Hart’s referring to County Cork, see IRA and Its Enemies p112

[11] See Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence pp. 88-91

[12] T Ryle Dwyer, The Squad, Mercier Press 2005, p190

[13] Ibid. p194

[14] Kearns Dublin Tenement Life 84-85

[15] Kevin C Kearns Dublin Voices an Oral Folk History, Gill & MacMillan, Dublin, 1998. p98-104 (Interviewed 1996)

[16] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p79

[17] The Drumcondra Murders, the Cairo Gang http://www.cairogang.com/other-people/british/castle-intelligence/incidents/drumcondra/drumcondra.html

[18] James Cahill BMH WS 503

[19] The Last Post, p 100-128

[20] Ibid.

[21] Sheehan, fighting for Dublin p114

[22] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin p39

[23] Irish Times March 29 1921, 5 July 1921.

[24] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin p44-45

[25] James Cahill MBH WS 503

[26] Sheehan, William, Fighting for Dublin, p.60

[27] Joost Augusteijn, Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare, p 173

[28] Maire Comerford Papers UCD LA/18

[29] Charles Townshend, The Republic, The Fight for Irish Independence, Gill & MacMillan 2013, p. 290

[30] New York Times, July 12, 1921

[31] In Mulcahy Papers, P7A/48

[32] The figure is from Eunan O’Halpin’s ‘Counting Terror’ in Fitzpatrick Ed. ‘Terror in Ireland’ is 309 killed in Dublin. Though this may overestimate violence in Dublin a little as it includes those wounded elsewhere who died in hospital in the city. The death toll included at least 58 IRA members (per the Last Post), 25 British Army soldiers killed in action ( Per their report re-published in Wiliam Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p130 though more died there due to accidents, illness or suicide) and about 40 police, which would indicate well over 150 civilian fatalities in the city.

[33] See the Last Post p100-128

[34] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p129-130

[35] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin, p129-130 and the Cairo Gang website, here http://www.cairogang.com/soldiers-killed/list-1921.html

[36] Richard Abbot, Police Casualties in Ireland. It does not seem reasonable as some studies do, to include as conflict related casualties those soldiers, guerrillas or civilians who died of illness such as the ‘Spanish flu’ in 1918-19, which killed at least 2,600 people in Dublin alone. Padraig Yeates A City in Wartime p270-273

[37] Sheehan, Fighting for Dublin p.79.