‘A policy of Passive Resistance’: Sinn Féin and Abstentionism – an historical overview

For over 100 years now, elected Irish Republican politicians have refused to take their seats in the British Parliament. Kerron Ó Luain tells the story of abstentionism.

In the aftermath of the 2017 UK elections much of the political discourse has focused on Sinn Féin’s policy of abstention from Westminster.

Indeed, an online poll published in the Belfast Telegraph recently, which surveyed support for the policy among Sinn Féin’s voter base, is only the latest in a series of pieces on the issue carried in both Irish and British news outlets since the 8 June election.

The likelihood of hung parliaments in London becoming more frequent, as a result of the polarisation of British society, as well as the potentially unstable nature of the Tory/DUP alliance, will see the spotlight continue to be shone on Sinn Féin, who refuse to use their votes in the Westminster Parliament.

Following the 2017 UK elections, it has been speculated that Sinn Fein will drop their policy of abstaining from the British Parliament at Westminster.

Added to this is the SDLP’s complete wipe out in terms of representation in London and Sinn Féin’s ascendancy electorally among northern nationalists, (holding seven seats in Westminster, their highest total ever), all of which potentially provides the party with the balance of power in Britain should they wish to use it.

As a result, the speculation from media sources that the party will move away from its historic abstentionist position in relation to the British parliament is likely to mount in the months and years to come.

It is timely, therefore, to cast our eye back in history and examine the policy’s nineteenth-century roots, as well as to elucidate on how changing political conditions since it first began to be practiced have seen the understanding and application of the abstentionist policy transform over time.

Pre-Act of Union

The original Irish republicans of the 1790s, the largely Presbyterian United Irishmen, although agitating initially on a constitutional basis for reform of the laws governing the participation of Catholics in civic life, were soon driven towards revolutionary methods in 1798 due to the obstinacy of the British colonial government.

The restricted franchise of the late eighteenth century and the ascendancy dominated parliament on College Green, election to which was through a system of patronage, militated against democrats such as the United Irishmen participating in the Irish House of Commons.

Although Lord Edward Fitzgerald, the Kildare United Irishman and landlord, sat in parliament with the opposition Irish Patriot Party headed by Henry Grattan, abstentionism was, by and large, not a strategic consideration Wolfe Tone and the leaders of the 1798 rebellion or Robert Emmet (who staged another rising in 1803) were forced to grapple with.

Young Ireland and the origins of abstentionism

Following the Act of Union 1800 – introduced in the wake of Tone’s 1798 rebellion, abolishing the Irish Parliament in Dublin – Irish MPs instead travelled to the British parliament at Westminster.

As Daniel O’Connell’s campaign for Repeal of the Union and restoration of the Irish Parliament continued into the mid-1840s, it was Young Irelander Thomas Davis who first proposed a motion to abstain from parliament during a meeting of the committee of the Repeal Association in 1845.

Young Irelander Thomas Davis who first proposed a motion to abstain from parliament during a meeting of the committee of the Repeal Association in 1845.

Initially, some Repeal MPs, including O’Connell’s son John O’Connell, withdrew from Westminster. However, they soon buckled under pressure exerted by the Westminster administration and returned to take their seats as committee members. It was left to another leading Young Irelander, William Smith O’Brien, to engage in a public protest by refusing to take his seat; earning him a term of imprisonment in London.

Prior to his arrest O’Brien had penned a letter in which he outlined the reasons for his refusal to take up his seat, stating that:

“Experience and observation have at length forced upon my mind the conviction that the British parliament is incompetent through want of knowledge if not through want of inclination, to legislate for Ireland, and that our national interests can be protected and fostered only through the instrumentality of an Irish legislature”.

In 1847 – during the worst year of the Great Famine and following the secession of the Young Irelanders from the Repeal Association – the notion of abstention as a form of protest was raised by the Young Ireland-led Irish Confederation once more.

Shortly afterwards, the Irish Confederation turned its sights towards insurrection and staged a brief rising in the south-east in 1848. Consequently, abstentionism was not to be seriously considered as an effective tactic for another two decades.

The Fenian years

The expansion of the franchise by acts of parliament in 1850 and 1868 opened up new electoral possibilities for popular candidates. With the collapse of the military endeavours of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) following the unsuccessful rising of 1867 at Tallaght, County Dublin, republican strategists sought out new avenues to advance their objectives.

Fenian chiefs John O’Leary and C. J. Kickham had long favoured abstention and the establishment of an independent national council. From 1868, with the growth of a broad-based movement which demanded amnesty for Fenians arrested in the run-up to rebellion, this ideal seemed achievable.

The IRB sought to marry the policy of abstention with an attempt to institute a citizens’ defence force through channels within the amnesty movement. The victories of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in 1870, and the former Young Irelander John Mitchel (on two occasions), at by-elections in Tipperary on explicitly abstentionist tickets might have offered a sign of things to come.

Though some Fenians were elected on abstentionist tickets in the 1870s, Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party preferred to advance nationalist goals inside the Westminster Parliament.

However, other prominent nationalists at the time such as John Martin, a northern Presbyterian and lawyer, preferred to describe themselves as ‘independent nationalists’, rather than abstentionists. Though he took up his seat in Westminster until his death in 1875, Martin refused to vote on any legislation in the chamber and spoke only to register protest at British interference in Irish affairs.

More importantly, the political state of play in nationalist Ireland during the 1870s and 80s was determined to a large extent by Charles Stewart Parnell, chief of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), and fondly referred to as ‘the uncrowned king of Ireland’. Though he briefly considered utilising abstention as a tactical weapon, Parnell opted instead for a policy of aggressive obstructionism.

In co-operation with his erstwhile colleague Joseph Biggar, a Belfast merchant and one time IRB man, Parnell delayed the passage of coercive legislation on Ireland by making protracted speeches in the House of Commons.

Many grassroots Fenians supported Parnell and his attendance at Westminster, and some were particularly receptive of the Avondale native in his final years when, following the Kitty O’Shea scandal of 1890, he courted the support of the ‘hillside men’ once again.

Griffith’s Proposal

Parnellite politics had dominated Irish society in the latter quarter of the nineteenth century. But, with the emergence of the Irish-Ireland and Gaelic League movements during the 1890s, a cultural revolution began which provided recruits – and ideological ammunition – for newly emergent nationalist and republican forces at the turn of the twentieth century such as Sinn Féin.

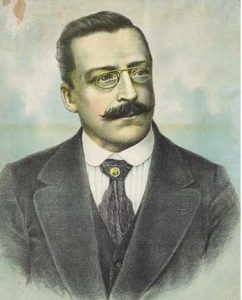

In 1904, Arthur Griffith (who would go on to found Sinn Féin the following year) authored The Resurrection of Hungary. In his book Griffith advocated a policy of passive resistance, which drew on the successful example adopted by Hungary in 1867. The Magyar nationalist members of parliament had refused to give recognition to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and instead took their seats in a native assembly.

Griffith envisaged the establishment of a national council in Ireland which would boycott all British judicial and state institutions – including Westminster.

Griffith envisaged the establishment of a national council in Ireland which would boycott all British judicial and state institutions – including Westminster. He also proposed a dual-monarchy system where the English monarch would rule both the Irish and British states, although this element was later shelved by republicans. Griffith railed against the oversimplified strategic false dichotomy between physical force and parliamentarism, which nationalists could see no way out of:

“A policy of Passive Resistance and a policy of Parliamentarianism are very different things, although the people of Ireland have been drugged into believing that the only alternative to armed resistance is speech-making in the British Parliament.”

Griffith also sought to promote protectionist economic policies and he urged the expansion of Irish manufacture, reforestation of the countryside and the setting up of a national bank, stock exchange and merchant navy. The component in Griffith’s program which urged people to ‘buy Irish’ was encapsulated in the maxim ‘burn everything English except their coal’.

Ideological ambiguities

From the outset, Sinn Féin’s abstentionist policy met with fierce criticism from the IPP. For example, James Mullan, a Cookstown solicitor and member of the party’s East Tyrone Executive, declared that the constituency would be ‘handed over to the enemies of their race’, i.e. local unionist politicians.

In Ulster, where abstention is still practiced today, the policy was always a more contentious issue. In districts with precariously balanced sectarian demographics, nationalist expediency in seeking to prevent Orange gentry and unionist figures from taking up electoral office took precedence.

Republicans and members of the Dungannon Clubs such as Bulmer Hobson and Seán Mac Diarmada (later executed in 1916), were quick to hit back at the IPP allegations, levelling the accusation at the constitutionalists that attendance at Westminster was neither practical nor, indeed, morally justifiable for self-declared nationalists.

In 1906, Dr Patrick McCartan, member of Clan na Gael and editor of Irish Freedom, stated that attendance at Westminster:

“was not only useless to Ireland, but also misrepresented Ireland before the world”.

The majority of nationalist Ireland (including rank-and-file IRB men who defied the wishes of their leadership) rejected abstention, especially after 1910 when the IPP under the command of John Redmond held the balance of power in Westminster.

This body of opinion was reinforced following the 1911 abolition of the House of Lords’ veto and the subsequent introduction of the Home Rule Bill by the Liberal Prime Minster Asquith the following year.

However, the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, and the opportunity seized on by the IRB and Irish Volunteers to stage a rising, changed the political landscape in Ireland irrevocably.

The abstentionist policy realised: the 1918 election

With the execution of the 1916 rising’s leaders, the rounding up and internment of civilians, the failed attempt to quell nationalist disaffection by holding the Irish Convention of 1917 and, finally, Prime Minister Lloyd George’s decision in early 1918 to introduce forced conscription to Ireland, the ground was made fertile for the introduction of a separatist policy.

Equally crucial was the fact that the IPP’s policy of attending at Westminster had been completely discredited. The British government were prepared to impose conscription despite the protestations of constitutional leaders such as John Dillon and Joseph Devlin in parliament. By the time the IPP decided to engage in a policy of ‘conditional abstention’ in early 1918 the damage had been done.

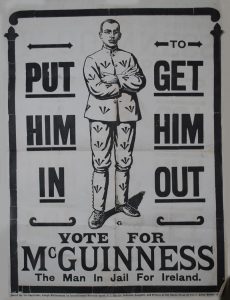

The successful election of Joseph McGuinness (imprisoned at the time in Lewes Gaol, England, for his part in the rising) as the first Sinn Féin candidate who stood on an expressly abstentionist ticket at the Longford South by-election on 9 May 1917, provided a promising trial run for the republicans.

As the general election of 1918 approached, Sinn Féin’s manifesto was patently abstentionist. It stated that the party would establish a republic ‘by withdrawing the Irish representation from the British parliament’ and setting up a national assembly.

As the general election of 1918 approached, Sinn Féin’s manifesto was patently abstentionist. It stated that the party would establish a republic ‘by withdrawing the Irish representation from the British parliament’ and setting up a national assembly.

When the party swept the board in December 1918 (demolishing the IPP forever in the process) it went about establishing the First Dáil, which gathered in the Round Room of the Mansion House, Dublin, in January 1919.

The idea first proposed by the IRB of the 1870s in which a citizens’ defence force would act as an armed corollary to a national assembly became reality when the IRA launched a military campaign on 21 January 1919, in the process sparking the War of Independence of 1919-21.

The abstentionist Dáil was afterwards bolstered by the setting up of republican courts throughout the country which further undermined British authority in Ireland.

Abstention in post-Partition Ireland

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 provided for the instituting of two separate legislatures in Ireland; one in Dublin and one in Belfast. This posed fresh dilemmas for Sinn Féin. Ultimately, the party contested elections to these two partitionist assemblies, but they did not take up their seats in either and instead inaugurated the Second Dáil; thus maintaining the abstentionist program.

Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, the foundation of the Irish Free State, and the split in the nationalist movement and subsequent Civil War, anti-Treaty Sinn Féin viewed the government in Leinster House as illegitimate. The anti-Treatyites reformed as Sinn Féin in 1923.

However, by 1926 the majority of anti-Treatyite Sinn Féin, led by Éamon de Valera, had founded Fianna Fáil. The party abandoned their policy of abstention from Leinster House following the assassination of Government minister Kevin O’Higgins in 1927. Due to punitive legislation passed after the killing they risked losing their seats if they did not take them up and took the required oath of allegiance to King George V upon entry into the Dáil in 1927. De Valera abolished the Oath after entering government in 1932.

Other republicans still viewed the ‘Free State’ Dáil and the Northern Ireland Parliament at Stormont as illegitimate British-imposed assemblies, however. In 1938 seven surviving anti-Treaty members of the 1921 Second Dáil, including Tom Maguire, bestowed what they believed was the authority of the Irish Republic – declared in 1916 – on to Seán Russell’s IRA Army Council. Afterwards, Sinn Féin and the IRA formally rejected both Leinster House and Stormont on the basis that the Army Council was the legitimate government of the Irish Republic.

The North erupts

Abstention became a bone of contention once more in 1969 when loyalist violence perpetrated against Catholics in Belfast and Derry, in response to demands for civil rights, instigated a split in the IRA and Sinn Féin.

Many traditionalists within the northern IRA such as Joe Cahill and Billy McKee, and some in the south such as Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, Seán Mac Stíofáin and Daithí Ó Conaill, were dismayed at the drift of the Dublin IRA leadership under Cathal Goulding towards Marxist politics.

Goulding’s class analysis led him to view the defence of Catholic districts in the north, then under attack by loyalist mobs, as sectarian. This reading, coupled with his move to abandon abstention of the three parliaments in Dublin, London and Stormont and take republicanism in a more political and electoral – rather than military – direction, fomented a split in the movement in late 1969 and early 1970. Goulding’s faction became known as the Official IRA. Its political wing was called Official Sinn Féin and later Sinn Féin-The Worker’s Party, while the traditionalists, who continued to abstain from the main assemblies, became known as the Provisional IRA and Provisional Sinn Féin.

The 1980s signalled a watershed for the abstentionist policy within republicanism.

Following the 1981 Hunger Strikes, the fielding of anti-H Block candidates, the election of Bobby Sands as an MP and the development of the ‘armalite and ballot box’ strategy, Provisional Sinn Féin, under the leadership of Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, moved in an electoral direction.

This saw the party take up council seats it had won in Northern Ireland in 1981 and contest elections to the Assembly in 1982 when it won 10 per cent of the vote – although it continued to abstain from that institution.

Nevertheless, this shift sowed the seeds of another split over abstention from Leinster House in 1986. At Sinn Féin’s Ard Fheis that year the Adams/McGuinness leadership sought to drop the policy of refusing to enter the southern parliament (though not Stormont). Adams framed this decision as a need for Sinn Féin to become more ‘political’:

“The central issue is not abstentionism. It is merely a problematic, deeply rooted and emotive symptom of the lack of republican politics and the failure of successive generations of republicans to grasp the centrality, the primacy and the fundamental need for republican politics”.

Led by Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, delegates in favour of maintaining abstention staged a walk out after the Ard Fheis voted by 429 to 161 to discontinue the policy. Prior to the walk out Ó Brádaigh gave a speech in which he stated that:

“Sitting in Leinster House is not a revolutionary activity. Once you go in there, you sign the roll of the House and accept the institutions of the state. Once you accept the Ceann Comhairle’s rulings you will not be able to do it according to your rules. You will have to go according to their rules and they can stand up and gang up on you, and put you outside in the street and keep you outside in the street.”

This strand of republican legitimism has persisted up to the present day with Ó Brádaigh’s grouping, Republican Sinn Féin, claiming allegiance to the Second Dáil and continuing to abstain from elections to Leinster House. Indeed, Tom Maguire conferred legitimacy on the Provisional IRA in 1969-70 and then on the Continuity IRA (which emerged out of the ’86 split) in order to maintain this legitimist tradition.

Abstentionism today

Contemporary Sinn Féin, meanwhile, dropped the policy of abstention with regard to the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont under the Adams presidency in 1998. When an executive was formed upon the signing of the Good Friday Agreement that year – which caused yet another split and the emergence of another group called the 32 County Sovereignty Movement – Sinn Féin took its seats in the northern Assembly.

In contrast to the earlier move towards acceptance of Leinster House of the 1980s, Sinn Féin was slower to participate in the Stormont parliament due to the continued conflict in the north and the entrenched Unionism prevalent within the Assembly and within its parallel state institutions.

Nineteen ninety seven saw Sinn Féin win its first seat in Leinster House when Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin was successfully elected in the border constituency of Cavan-Monaghan. Today Sinn Féin no longer question the legitimacy of Leinster House, as the party once did and hold 23 seats there. However, they continue to refuse to enter the British Parliament at Westminster.

Sinn Féin currently practices what they term an ‘active abstentionism’ in relation to Westminster based on a rejection of the oath of allegiance to the English Queen and the maintenance of Irish sovereignty.

Whatever the future holds for the policy within Sinn Féin with regards the one institution it no longer abstains from, Westminster, history shows that abstention has not always been – even among republicans – a black and white point of principle, but has at different times served as a means to an end, rather than an end in itself.

Further Reading

Arthur Griffith, The resurrection of Hungary: a parallel for Ireland (3rd edn., Whelan and son, Dublin, 1918).

Denis Gwynn, ‘Smith O’Brien and the “secession”’, in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, xxxvi, no. 142 (1947), pp. 129-140.

Fergal McCluskey, Fenians and Ribbonmen: the development of republican politics in east Tyrone, 1898-1918 (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2011).

- Bowyer Bell, The secret army: the IRA (3rd edn., Poolbeg, Dublin, 1998).

Owen McGee, The IRB: the Irish Republican Brotherhood from the Land League to Sinn Féin (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2005).

- S. O’Hegarty, The victory of Sinn Féin: how it won it, and how it used it (The Talbot Press, Dublin, 1924).

Dr. Kerron Ó Luain is an historian from Rathcoole, County Dublin. He received his doctorate from Queen’s University Belfast in 2016 and works in Fiontair agus Scoil na Gaeilge, DCU, on various digital humanities projects, among them dúchas.ie.