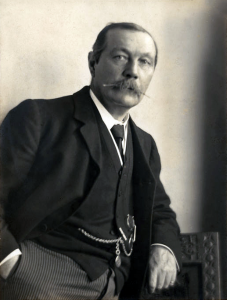

Arthur Conan Doyle and the Irish Literary Society

Jane Stanford on Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, and his links with Ireland.

The Anglo-Celtic race has always run to individualism, and yet there is none which is capable of conceiving and carrying out a finer ideal of discipline.

Arthur Conan Doyle, Through the Magic Door, XI

A hundred and twenty years ago, on the evening of February 13th 1897, Dr A Conan Doyle took the chair at a meeting of the Irish Literary Society in London. Doyle, intensely aware and proud of his Gaelic roots, described himself as an Anglo-Celt.

He was an omnivorous researcher in the British Museum and an accomplished historical novelist. He chose as his topic the eighteenth century wild geese, Irish exiles in France’s army. He also touched on Irish literature. Downey & Co. had begun the process of re-issuing the thirty-seven novels of Charles Lever. Lever, a prolific Anglo-Irish novelist and widely travelled physician, was, in his day, as popular as Thackeray and Dickens. With his rollicking, conversational style, his lively military fiction, he was a favourite of Doyle’s.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s grandfather was a Catholic Irishman.

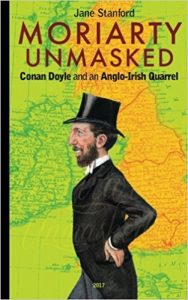

The Irish Literary Society, founded five years earlier in 1892, boasted an Irish brigade: Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, Australian politician and briefly Premier of Victoria, the folklorist and songwriter, Alfred Perceval Graves, Parnell’s biographer, Barry O’Brien, Michael MacDonagh, Times correspondent and author of The Home Rule Movement, Lord Russell of Killowen, the first Catholic Lord Chief Justice since the Reformation and the ex-MP for Mayo, John O’Connor Power, an inspiration for Doyle’s ex-Professor Moriarty, a seditious Irishman with ‘hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical kind’.

In June that year, Power would be present at ‘A Sheridan Night,’ giving the vote of thanks. It was the centennial year of Edmund Burke’s death and Power had marked his birthday, January 12th, presiding at a dinner attended by seventy nationalists. In the eighteenth century, Edmund Burke, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Oliver Goldsmith, all members of Dr Johnson’s literary Club, were an Irish brigade of their day, men of light and leading, fighting for liberal causes with panache and steely resolve.

1897 was the centennial year of Doyle’s grandfather’s birth. John Doyle was an Irish Catholic whose ancestral land had been confiscated under the draconian Penal Laws. In 1822, he left Dublin and moved to London with his wife, Marianne Conan. John was a gifted artist and the leading cartoonist of his age.

Irish nationalist activist John O’Connor Power, was an inspiration for Doyle’s ex-Professor Moriarty, a seditious Irishman with ‘hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical kind’.

In the faith and freedom tradition, he was staunchly Catholic, a pillar of his church. His son, Richard, ‘Dickie’, an illustrator with Punch, resigned from the magazine in protest when it took a belligerent stance against the re-established Catholic hierarchy and his friend, Cardinal Wiseman, Archbishop of Westminster.

Another son, Henry, retaining the Irish link, was a Director of the National Gallery of Ireland. Doyle’s father, Charles Altamont, the youngest, moved to Edinburgh. He illustrated his son’s A Study in Scarlet, a novel, which, for the first time, featured the consulting detective, Sherlock Holmes, and his chronicler, Dr Watson.

Those present at the Irish Literary Society evening were keenly aware that the following year was the centennial of the United Irishmen Rising. In 1798, French troops, led by General Humbert, landed on the west coast of Ireland, supplying troops for the rebellion. Victory at the Battle of Castlebar, leading to the proclamation of The Republic of Connacht, was short-lived.

The insurrection was swiftly quashed by British troops and the Irish Parliament, with the Act of Union, was dismantled. Ireland would henceforth be governed with military efficiency from Dublin Castle. The Union was not only to keep Ireland subject but to make England secure against French hostility and intrigue.

Doyle reflects in Through the Magic Door, ‘We know what Humbert did with only a few hundred men in Ireland – Humbert failed and the consequences with the loss of an independent legislature, were disastrous for the country.’

Plans were in train to mark the United Irishmen centennial with a new political party, the United Irish League. Chief Secretary Gerald Balfour, ‘killing Home Rule with kindness’, was preparing far reaching local government legislation. The Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 dovetailed neatly with the new party, providing structures and platforms for it to build on. Three quarters of the seats in the county, urban and rural district councils were filled by Catholics, effectively destroying the power of the Ascendancy, the landlord class.

Doyle was against Home Rule in the 1880s and 1890s but later conceded that his view may have been mistaken.

By descent and parentage, a Southern Irishman, Conan Doyle had spent holidays in Ireland with his mother’s family in Lismore, County Waterford. In London he was close to the Irish community and at home with his Celtic comrades-in-letters.

For many years, he opposed Home Rule, the restoration of an Irish parliament, advocating a more gradual approach. An Imperialist, he feared the disintegration of the Empire and civil war in Ireland. He was hostile to the Catholic Church’s aggressive proselytizing and was convinced that Home Rule meant Rome Rule. Protestant Ulster would oppose it vigorously. Ireland was not ready for independence. Local government would provide training and experience for political responsibilities.

Doyle was a late convert to Home Rule and conceded in Memories and Adventures, ‘Perhaps we were wrong. However that was my view at the time’. He wrote of his role in the resolution of the Irish Question: ‘Who is there outside England who really knows the repeated and honest efforts made by us to settle the eternal Irish Question and hold the scales fair between rival Irishmen?’

Doyle was a late convert to Home Rule and conceded in Memories and Adventures, ‘Perhaps we were wrong. However that was my view at the time’. He wrote of his role in the resolution of the Irish Question: ‘Who is there outside England who really knows the repeated and honest efforts made by us to settle the eternal Irish Question and hold the scales fair between rival Irishmen?’

Jane Stanford is the author of ‘Moriarty Unmasked: Conan Doyle and an Anglo-Irish Quarrel’, Jane Stanford, Carrowmore, 2017 and ‘That Irishman: the life and times of John O’Connor Power’, Jane Stanford, History Press Ireland, 2011. See her blog at www.thatirishman.com