Book Review: The Dublin Lockout, 1913: New Perspectives on Class War & its Legacy

Editors: Conor McNamara and Pádraig Yeates

Editors: Conor McNamara and Pádraig Yeates

Irish Academic Press, 2017.

Reviewer: Gerard Noonan

The centenary of the 1913 Lockout sits somewhat awkwardly in the ‘Decade of Commemorations’. What did an industrial relations dispute have in common with a rebellion and a subsequent war against imperial rule? Was it merely that a significant figure in the Lockout, trade unionist James Connolly, was also a leader of the 1916 Rising? Or did the Lockout give rise to class conflict that provided a motivation for events over the rest of the decade?

What did an industrial relations dispute have in common with a rebellion and a subsequent war against imperial rule?

This is just one question thrown up by The Dublin Lockout, 1913: New Perspectives on Class War & its Legacy, a collection of eleven essays arising from the 2013 Byrne-Perry Summer School held in Co. Wexford on the theme ‘Men and Masters – The Great Lockout of 1913’. Various aspects of the Lockout are covered, from the media’s treatment of the workers to the attitudes of Belfast and Irish-America.

Other essays touch on the Lockout while addressing topics related to it, including the Irish Citizen Army, Dublin’s newsboys, the career of socialist republican Helena Moloney, and the role of class in the Irish Revolution. Sympathetic to the workers’ plight without being uncritical, all the essays use a variety of primary and secondary sources.

As Pádraig Yeates shows in his detailed chronology of the Lockout, it began in July 1913 when William Martin Murphy, the most powerful businessman in Dublin, dismissed workers from his Dublin United Tramway Company for refusing to repudiate their membership of the radical Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU).

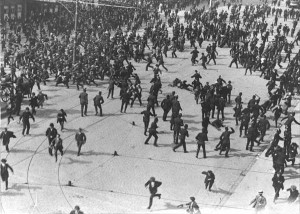

By late September, 25,000 workers had been locked out by Murphy and other employers. The standoff ended in late January 1914 when, after months of riots, demonstrations, trials and a few deaths, the workers returned to work on the employers’ terms. The cost to the Dublin economy was about £2.3 million, when, by way of comparison, the average weekly wage of an unskilled labourer was about £1.

What caused this episode of industrial unrest unparalleled in Irish history? The contributors differ.

In her essay on oral history and the Lockout, Mary Muldowney says that it was ‘essentially about the right of all workers to belong to the trade union of their choice and for employers to be obliged to recognize and negotiate with that union’.

Others, however, especially Yeates, emphasize the importance of syndicalism in the ideology of Jim Larkin and James Connolly, the leaders of the ITGWU. Syndicalism aimed to unite all workers in one big union, overthrow capitalism through a general strike and construct a new economic order based on co-operative ownership of the means of production by the workers. Obviously, this was a more revolutionary motivation than the desire to secure the right to free collective bargaining.

Some contributors argue that the Lockout was a dispute about the right to join a union, others that it was motivated by radical syndicalist ideology.

Irish public opinion was overwhelmingly hostile to the workers. As John White argues, ‘Prejudice based on social class-dominated depictions of the striking workers and the urban poor during the 1913 Lockout. Those involved were continually portrayed within a framework of moral degeneracy, representative of the deep social chasm that existed between ‘respectable’ Ireland and the urban poor of Dublin’s slums.’

‘Larkinism’ was denounced as atheistic and socialistic. The Lockout posed ideological problems for Irish nationalists, as class conflict jarred with their traditional depiction of the Irish as united in the face of the oppressive British. With the conflict occurring just a year before the country was scheduled to achieve home rule, nationalists feared that it portrayed the Irish internationally as unfit to rule themselves.

As Meredith Meagher notes in an interesting essay, the Irish World, the newspaper of home rulers in America, although fitfully sympathetic to the workers, ‘contrasted the actions of the ITGWU with the perceived reputation that ‘home rulers’ in the United States cultivated as respectable, law-abiding ‘citizens-in-waiting’ who would rely on legislative and constitutional measures to address their nationalist grievances’.

Even sympathetic Republicans were hostile to aspects of the strike. Radicals Helena Moloney and Rosamond Jacob were revolted by the ‘unwholesome Englishness of Larkin & the strike’. There was an ‘English’ dimension to the Lockout. Larkin lobbied the British Trade Union Congress to strike in sympathy with their Irish comrades. It refused, aware that ninety-five per cent of sympathetic strikes in the recent past had ended in defeat for the workers. Instead, it sent about £93,000 in strike pay and provisions.

The employers also received help from Britain, with the British Shipping Federation contributing, along with others such as Lord Iveagh, the head of the Guinness dynasty, to a fund totalling around £20,000 that helped to steel their nerve.

Both strikers and employers in Dublin received aid from sympathisers in Britain.

And, famously, a scheme by British socialist Dora Montefiore to send the children of locked-out workers to the homes of trade unionists in England for temporary respite raised the hackles of Catholic Ireland, with members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians physically preventing the children from boarding a ship to Britain lest they be stolen from the faith of their fathers. Hence, class prejudice, nationalism, sectarianism and Anglophobia characterized the popular reaction to the Lockout.

If the public was hostile to the workers, so too were other trade unionists. Book binders and printers, engineers and carpenters passed the picket lines. Likewise, the drapers’ assistants, members of the most militant white collar union, continued to go about their work. The failure to get these unions to strike in sympathy was a serious failure on the part of Larkin and Connolly.

The latter also committed a ‘major blunder’ in November 1913, argues Yeates, when he ordered the dockers in Dublin port to join the strike. Heretofore, the dockers had been able to disrupt trade by means of a ‘go-slow’ tactic, all the while continuing to receive their wages from which they contributed their union dues, dues badly needed to support the strike pay of their comrades. Now, by walking off the job, they were on strike pay too and were replaced by non-union labour from Britain.

‘In the context of the revolutionary decade, the legacy of the Lockout was residual.’ It is hard to disagree with Yeates’s conclusion.

Between 1914 and 1916, scared by defeat in the Lockout and shocked at the sight of Irish, British and French workers fighting against German and Austrian workers in a war that he believed was motivated purely by imperial aggression, Connolly’s socialist republican politics began to lean more towards republicanism. The increasingly close relations between the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) and the nationalist Irish Volunteers is evidence of this.

Originally established during the Lockout as a means of occupying the workers’ time and protecting their meetings from the violent attention of the police, under the leadership of Connolly and his deputy Michael Mallin the ICA became a more formal military organisation, with drill practice, marches, uniform etc. The committed membership rarely exceeded three hundred. Most workers did not join the organisation, because of lingering bitterness towards Connolly and the ITGWU regarding the Lockout, the lack of socialist consciousness, and perhaps snobbery on the part of skilled workers towards a body dominated by the unskilled.

Connolly led 212 ICA members, including 27 women, into the 1916 Rising. (‘It is almost certain that some of those who had fought the police in 1913 were among the ‘rabble’ who turned on the rebels during and after Easter Week,’ writes Brian Hanley.) Eleven were killed in the fighting, followed soon afterwards by the executions of Connolly and Mallin. As Conor McNamara reveals, the ICA thereafter was a pale shadow of its former self. Encountering hostility from a trade union hierarchy wary of revolution and suffering feeble leadership itself, the workers’ militia became a social club riven by personal animosities.

‘In the context of the revolutionary decade, the legacy of the Lockout was residual.’ It is hard to disagree with Yeates’s conclusion. Despite the appearance of the red flag and workers’ soviets, the next upsurge in industrial unrest, between 1917 and 1923, had little to do with syndicalism and more to do with a desire for simple wage increases. Ultimately, because of the influence of religion and the importance placed on property rights, the Irish were too conservative to engage seriously with revolutionary class politics.