Book Review: The Post Office in Ireland, an Illustrated History

By Stephen Ferguson,

By Stephen Ferguson,

Publisher: Irish Academic Press, (2016)

Reviewer Ruairí Ó hAodha

A truly illustrated history

Stephen Ferguson is Assistant Secretary of An Post and the curator of its Museum and Archives. He has already published on diverse aspects of postal history in Ireland, from post boxes to nineteenth century robberies and reward notices. He has also written extensively on the GPO, its staff and the effects on the service of the 1916 Rising.

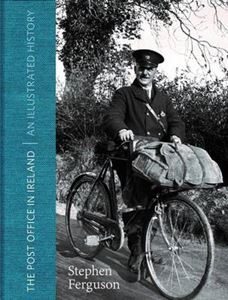

At almost five hundred pages, his latest work is undoubtedly the magnum opus. The first thing that needs to be mentioned about The Post Office in Ireland, an illustrated history is that its front cover includes an impressive black-and-white photo of Co. Offaly postman Arthur Doran in 1930. It is a pleasant portrait Mr. Doran, his bag and bicycle, but in some respects does not do full justice to what follows within.

Ferguson’s book stands out as one of the most uniquely and impressively-illustrated books on modern Irish history published in recent times.

In spite of the recent behemoth Atlases of the Irish Famine and Revolution, Ferguson’s book stands out as one of the most uniquely and impressively-illustrated books on modern Irish history published in recent times. It is handsomely typeset and beautifully bound.

In fact it would not be going too far to say that, in reading it, one is given a thorough tour through An Post’s Museum and Archives. It also includes numerous illustrations and memorabilia that Ferguson has himself collected, along with copious colour portraits and maps from the National Gallery and National Archives (of the Republic and Northern Ireland).

His chapters covering telegraphy and telephony include a number of rare Fr. Browne photos of the brave chaps who erected the first telephone poles in the 1920s and 30s. It would make an ideal Christmas gift for the lover of social history in anyone’s life. Those interested in Irish art, print, post or Christmas cards, letter-writing and philately will discover a veritable treasure trove at their fingertips. It is of value as much to collectors as to researchers.

In recent years the Post Office has featured heavily in media discourse regarding its central social role in rural communities with declining populations. Ferguson’s greatest achievement in this work is to show just how central the postal services and how wide their remit have been to all aspects of national development throughout the centuries. Their activity has been a fulcrum to so much of the national story.

Everyone is familiar with the now iconic status of the GPO, but few will be familiar with the story of Napper Tandy raising an ‘Erin go Bragh’ standard at the post office on the Donegal island of Inishmacadurn in the autumn of 1798. A local tale recounts that one of the French general’s left a gold ring to the postmistress of the island in thanks for her hospitality.

It is a testament to the centrality of post that the earliest surviving document from Irish history, and one of the very few surviving written witnesses from beyond the confines of the Roman Empire in fact, is St. Patrick’s excommunicatory Letter to the soldiers of Coroticus. Toward the end of it we are given something of the challenges then facing communication we now take for granted:

‘I ask earnestly whatever servant of God is courageous enough to be a bearer of this letter, that it in no way be withdrawn or hidden from any person. Quite the opposite – let it be read before all the people, especially in the presence of Coroticus himself.’

Nor does Ferguson neglect the far less popular Laudabiliter of Pope Hadrian IV, and its implications on the whole of Irish history, in spite of the long debate amongst historians on the text’s contemporary significance. The book follows a clear and thorough chronological progression, beginning with the first stirrings of a centralized postal system in late medieval France.

The first Irish postmaster was magically-named Melchior van Pelken, appointed in 1618, but the development of a postal system proper had to wait until the Cromwellian era

The first Irish postmaster was magically-named Melchior van Pelken, appointed in 1618, but the development of a postal system proper had to wait until the Cromwellian era (p. 43). There were from the start serious challenges to the new system; as with many of the new trades of the era, centralization was a constant government concern; the crown wary of all ‘disavowed messengers, Curriers or foote Posts.’ Moreover London traders and guilds had their vested interests, and swiftly sought as they did in other areas like printing or wine-selling, a monopoly over the Irish postal trade.

Geography played a significant role too; irrespective of what was stated in official documents, territory was inevitably difficult to govern effectively, if it was only possible to cross the Shannon by foot or horse. Even after the coming of the mail coaches of the eighteenth century, the ‘roads’ from Athlone to Galway or Limerick could still prove virtually impassable in winter. It was the coming of the railways that cemented the Post Office’s hold over the communication corridors of the country and the same period (1830-1920) saw much closer integration with the service in Britain.

The railway was integral too to the development of telegraphy. While the electrification and ‘telephonication’ has been addressed in previous studies, Ferguson’s book delivers a fascinating and insightful account on the development of telegraphy and the revolution it wrought, hailed as it was at the time as a ‘bond of perpetual peace and friendship.’

Once again the first steps in this new development were taken in France by Claude Chappe and his brothers, but Ireland produced at least three figures that made major contributions to the telegraph. Chief amongst these was the Limerick-born medic William O’Shaughnessy, who through a keen eye and a stroke of good fortune, noticed that when a wire fell into a large tank at his medical college in Edinburgh, that when submerged in water, only one insulated wire was required for clear two-way communication. O’Shaughnessy went on to pioneer the electrical telegraph throughout much of the Indian subcontinent (p. 240).

On the technical side, Ferguson gives great insight into the first transatlantic cables, which were no small achievements of human ingenuity, given that they had to be laid down at a depth of 16,000ft, across 3,000 miles. The transatlantic cables from were so heavy, made as they were from copper with iron insulation, that two ships had to carry two respective halves to the mid-Atlantic, splice them there, and then sail back to opposite sides of the ocean.

The first transatlantic cables, which were no small achievements of human ingenuity, given that they had to be laid down at a depth of 16,000ft, across 3,000 miles.

The second Irish pioneer in this area was Robert Halpin of Wicklow town. Known at the time as ‘Mr. Cable’, perhaps ‘father of global communications’ might be more fitting. He laid the first French-Canadian cable, then one going from Bombay through Aden to Suez and later oversaw the linking of Madeira with Brazil, thereby linking four continents in one career. Stories of similar interest are covered in the subsequent chapter on the spread of the telephone.

The last chapters of The Post Office in Ireland cover more recent times, focusing especially on the workers and their lives; postmen of course, but sorters, couriers, telephonists, railway carriers and packet ship crew. The life of the sorter was no walk in the park! The post office was a venue that gave much employment to women at an early stage; it also had (and still has) an essential social role, as an integrator and sustainers of dispersed communities, the stories of which will entertain any reader.

There are some exemplary appendices at the end, including a list of all the Postmaster Generals since the beginnings of the service in the seventeenth century, along with a fulsome bibliography for those in search of further specific detail. Stephen Ferguson should be commended for his Trojan work. There is something in this book for all historians of modern Ireland. The depth of his scholarship becomes clear as one reads his book and realizes that the history of the Post Office is in many ways the history of Ireland.