1888: An American Journalist in Ireland Meets Michael Davitt & Arthur Balfour

By Mark Holan

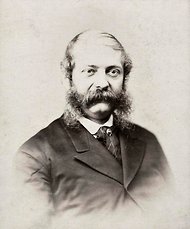

American journalist William Henry Hurlbert traveled to Ireland in 1888 to report on “the social and economical conditions of the Irish people as affected by the revolutionary forces which are now at work in the country.”[1]

For six months, he considered “things great and small, and people high and low”[2] as he crossed the country by rail and jaunting car; from private offices in Dublin Castle to remote cabins in Donegal; from troubled estates in Cork and Kerry to Orange halls in Belfast.

Hurlbert’s arrival coincided with a period of resurgent agrarian agitation, what historian Lewis Perry Curtis, Jr. later called “The Second Land War.”[3] The period 1886 to 1891 was known as the ‘Plan of Campaign’, in which the Irish National League, headed by nationalist leader Charles Stuart Parnell, agitated, through rent strikes and boycotts, against evictions, and for reduced rents for tenant farmers.

The period 1886 to 1891 was known as the ‘Plan of Campaign’, in which the Irish National League, headed by nationalist leader Charles Stuart Parnell, agitated, through rent strikes and boycotts, against evictions, and for reduced rents for tenant farmers.

Violence flared on both sides, with destruction of landlords’ property and sometimes killing of landlords and their agents on one side and government repression on the other.

The British government had begun to enforce tougher coercion laws, under which suspects could be imprisoned by a magistrate without a trial by jury and ‘dangerous’ associations, such as the National League, could be prohibited. The 1887 Coercion Act was passed the previous summer to stop violence and stymie political activism. The legislation was prompted, in part, after The Times of London published its sensational “Parnellism and Crime” series, which sought to link to the Irish Parliamentary Party leader to the 1882 murders of two British officials in Dublin’s Phoenix Park.

During Hurlbert’s travels, Pope Leo XIII issued a decree warning his Irish flock against boycotting and the rent-withholding Plan of Campaign. American diplomats in Ireland corresponded with their superiors in Washington, D.C., about the alarming rise of westbound emigrants,[4] while Hurlbert questioned the role of the Irish already in America with the affairs of their homeland. His trip ended as the special judicial commission in London began hearings on the allegations against Parnell and other Irish nationalists.

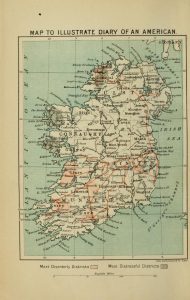

Hurlbert’s diary-style, social-political travelogue, titled Ireland Under Coercion: The Diary of an American, was published in late summer 1888. In America, The Literary World explained to its readers: “The rule of the Land League is, in Mr. Hurlbert’s opinion, the only coercion to which Ireland is subjected; and the title of his volume has reference to this view.”[5] Reviews on the east side of the Atlantic reflected the late 19th century politics of their respective journals.

The Times, organ of Britain’s ruling Tory party, described Ireland Under Coercion as an “entertaining as well as instructive …. collection of evidence on the present phase of the Irish difficulty, the genuineness of which it would be idle to impeach.”[6]

The pro-Parnell United Ireland called it a “libelous book on Ireland … fit to take its place amongst other grotesque foreign commentaries.”[7] Father Patrick White, a pro-tenant priest whom Hurlbert interviewed in Clare, complained the American journalist “libeled me, and libeled me unsparingly,” in his scathing, 32-page reply pamphlet, Hurlbert unmasked: an exposure of the thumping English lies of William Henry Hurlbert in his ‘Ireland Under Coercion’.[8]

Much of Hurlbert’s political analysis was soon upended by the revelation of Parnell’s extramarital affair, rupture among constitutional nationalists, and the “long gestation”[9] that followed the death of Ireland’s “uncrowned king.”

Hurlbert, a witness to the bloodshed of the American Civil War 20 years earlier, correctly anticipated that “establishing the independence of Ireland against the will of Ulster” was “little short of madness.”[10]

Ongoing agrarian reforms in Ireland quickly dated his ardent pro-landlord views. Culturally, he recognized and praised the talents of the young W. B. Yeats, who had four poems in the just-published Poems and Ballads of Young Ireland, and also noted Douglas Hyde’s contribution of a poem about the four-year-old Gaelic Athletic Association.

By 1891, after publishing a similarly-styled book about France, Hurlbert’s once respected reputation as a New York City newspaper writer and editor began to wane. He was tarnished in a tawdry courtroom melodrama, which exposed his adulterous affair that began the year before his trip to Ireland. In this regard, his fate was similar to Parnell. Hurlbert died in Italy in 1895, aged 68.

Hurlbert was hostile to the Irish land movement and to Irish nationalism more generally. He saw it leader Parnell as a cynical opportunist.

During his 1888 Ireland travels, Hurlbert interviewed many of the leading characters of the day: Chief Secretary of Ireland Arthur Balfour; agrarian agitator Michael Davitt; Fenian John O’Leary; estate owner Charles Talbot Ponsonby and other landlords, including the limbless Arthur MacMurrough Kavanagh; Father White and other pro-tenant priests; Members of Parliament; and ordinary citizens, most of them left unnamed.

He did not interview Parnell, son of an American mother, whom he disdained as a political opportunist. In the 130 years since Ireland Under Coercion was published, Hurlbert’s work has been sparingly cited by Curtis, Myles Dungan, and a few other historians.

Ireland Under Coercion also is included in Travellers’ Accounts as Source-Material for Irish Historians, a reference by Christopher J. Woods, and The Tourist’s Gaze, Travellers to Ireland, 1800 to 2000, edited by Glen Hooper. Hurlbert’s book is a mosaic of 1880s Ireland. In some passages, he poetically described Irish landscapes, such as Donegal’s “glorious and ever-changing panoramas of mountain and strath,” where he visits a “warm and comfortable” cabin with “a peat fire smouldering, sending up, to me, most agreeable odours.”[11]

He detailed many still surviving landmarks, including the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin; Drogheda viaduct, Blarney Castle; Kilkenny Castle; Sir Walter Raleigh house in Youghal, County Cork; Botanic Gardens, Belfast, and numerous churches and ruins.

But Hurlbert’s thoughts on the agrarian agitation and nationalist movement are the core of Ireland Under Coercion. His interactions with Balfour and Davitt, in particular, illustrate his views.

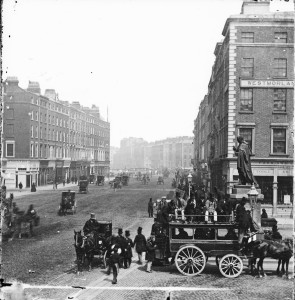

DUBLIN ARRIVAL

Hurlbert arrived in Ireland on 30 January 1888, accompanied by Lord Ernest Hamilton, who was elected three years earlier as MP for North Tyrone. A dockside news vendor who recognized the conservative politician “promptly recommended us to buy the Irish Times and the Express,” then “smiled approval when I asked for the [nationalist] Freeman’s Journal also,” Hurlbert wrote.

His attention was drawn to the Freeman’s report about the previous evening’s nationalist demonstration in Rathkeale, County Limerick, about 20 miles southwest of Limerick city.

Thousands of men from counties Limerick, Kerry and Clare attended the rally to hear a speech by Davitt. To Hurlbert, it was “chiefly remarkable for a sensible protest against the ridiculous and rantipole abuse lavished upon Mr. Balfour by the nationalist orators and newspapers.”[12]

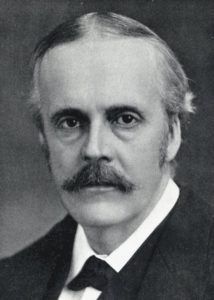

Arthur Balfour, the Chief secretary was nicknamed ‘Bloody Balfour’ for his strict imposition of the Coercion Act.

Arthur Balfour was the Chief Secretary for Ireland, head of the British administration in the country. He was much resented by nationalists for his strict enforcement of the Coercion Act. Four months earlier, police had fired on a crowd of demonstrators in County Cork, killing three, in what became known as the ‘Mitchelstown massacre’, earning him the nickname ‘Bloody Balfour’.

According to the Freeman’s coverage, Davitt said that Balfour:

“…is not a man who cares very much about the names he is called, and calling names, let me add, is not a very scientific method of fighting Mr. Balfour’s policy. Calling him ‘bloody Balfour’ may be a truthful description … but its constant use in newspapers and on platforms is becoming what the Americans term a ‘stale chestnut.’ … What we have got to recognize is the policy of this man, and what we have got to do is, to beat that policy by cool, calculating resistance.”[13]

Hurlbert wrote that “Davitt has the stuff in him of a serious revolutionary leader … bent on bringing about a thorough Democratic revolution in Ireland. I believe him to be too able a man to imagine … this can be done without the consent of Democratic England [and he knows] that to abuse an executive officer for determination and vigour is the surest way to make him popular.”[14]

In fact, Davitt also criticized Balfour during the Rathkeale speech. Davitt noted that at the current pace of arrests under the 1887 coercion law, it would take the chief secretary more than 500 years to imprison all the supporters of Irish nationalism and tenant rights:

“If we judge of what he can do to save the life of Irish landlordism by all he has performed up to the present, we need have very little apprehension about the final result. … He will discover, if he has not done so already, that imprisonment will not beget loyalty, nor plank beds gratitude to the power he represents. It is with a nation, as with an individual, a tussle with persecution brings out great qualities of endurance, the courage of conviction, and a faith which scorns to abdicate to brute force.”[15]

MEETING BALFOUR

Within hours of his arrival, Hurlbert visited the Chief Secretary, Arthur Balfour at Dublin Castle. The American described the seat of the British government administration in Ireland as “no more of a palace than it is of a castle … People go in and out of it as freely as through the City Hall in New York.”

Balfour, then 39, was in the job less than a year after being appointed by his uncle, Prime Minister Salisbury. He was “in excellent spirits; certainly the mildest mannered and most sensible despot who ever trampled the liberties of a free people,” Hurlbert wrote, tongue only partly in cheek. “He was quite delightful about the abuse which is now daily heaped upon him in speeches and in the press.”

Hurlbert asked Balfour about Davitt’s statement the previous evening at Rathkeale, where he suggested his supporters to stop using the phrase “bloody Balfour.”

Hurlbert wrote sarcastically that Balfour was: ‘certainly the mildest mannered and most sensible despot who ever trampled the liberties of a free people’.

“Davitt is quite right, the thing must be getting to be a bore to the people, who are not such fools as the speakers take them to be,” Balfour replied. “One of the stenographers told me the other day that they had to invent a special sign for the phrase ‘bloody and brutal Balfour,’ it is used so often in the speeches.”[16]

This sounds a little dubious, perhaps the self-aggrandizing anecdote of an up-and-coming politician to the foreign journalist. It appears from this passage of the book that their interview did not last long. Hurlbert later insisted that Balfour had “obviously unaffected interest in Ireland.”

Curtis has noted that Balfour accommodated Hurlbert’s Ireland visit in the hope his reporting would have some influence in America.[17] “For Balfour the struggle in Ireland was between the forces of law and decency on the one hand and those of organized rebellion and robbery on the other,” Curtis wrote. A week after Hurlbert’s visit, Balfour wrote to a colleague, “To allow the latter to win is simply to give up on civilization.”[18]

Hurlbert also sought an interview with Davitt, “who was not to be found at the National League headquarters, nor yet at the Imperial Hotel, which is his usual resort.” He admitted to “sharing the usual and foolish aversion of my sex to asking questions on the highway” as he got confused by the transition of one of Dublin’s main boulevards from Sackville Street to O’Connell Street.[19]

HOME RULE

In 1880, Davitt and Parnell partnered in an effort to link agrarian reform and domestic political autonomy for Ireland, called Home Rule. Both men visited the United States that year to generate financial and political support for their cause from the Irish in America.

Six years later, despite support from then Liberal British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, unionist MPs defeated Home Rule legislation. In Ireland Under Coercion, Hurlbert wrote that the 1886 bill would have made Gladstone and the British government “the ally and the instrument of Mr. Parnell in carrying out the plans of Mr. Davitt, [American socialist] Mr. Henry George, and the active Irish organizations of the United States.”

Hurlbert also recognized the Home Rule effort was not over:

“How or by whom Ireland shall be governed concerns me only in so far as the government of Ireland may affect the character and the tendencies of the Irish people, and thereby, the close, intimate, and increasing connection between the Irish people and the people of the United States, may tend to affect the future of my country. …

[In the wake of the failed 1886 bill] ‘Home Rule for Ireland’ is not now a plan–nor so much as a proposition. It is merely a polemical phrase, of little importance to persons really interested in the condition of Ireland, however invaluable it may be to the makers of party platforms in my own country, or to Parliamentary candidates on this side of the Atlantic. … [It] has unquestionably been the aim of every active Irish organization in the United States for the last twenty years … [and] Parnell is understood in America to have pledged himself that he will do anything to further and nothing to impede.”[20]

During his stay in Dublin, Hurlbert met with several members of the Balfour administration and MPs who opposed any reform to the 88-year-old Act of Union. One unidentified Catholic unionist from southern Ireland told him it would be “madness to hand Ireland over to the Home Rule of the ‘uncrowned king’ (Parnell).” Hurlbert also attended a speech by Colonel Edward James Saunderson, MP for North Armagh, who asked his audience whether they could ever imagine being governed by “such wretches” as the Parnellite nationalists.

“Never,” the crowd replied in what Hurlbert described as “a low deep growl like the final notice served by a bull-dog.” It was a response echoed 97 years later by Ian Paisley and his unionist supporters outside the Belfast City Hall.[21]

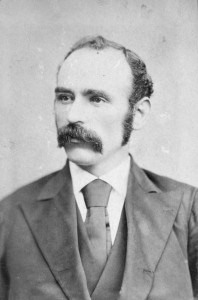

MEETING DAVITT

“Mr. Davitt spent an hour with me today, and we had a most interesting conversation,” Hurlbert reported in the 15 February 1888, entry of Ireland Under Coercion.[22] The American journalist connected with the agrarian activist during a short side trip to London; having been called away from his travels in Ireland for reasons left unexplained in the book. Perhaps his affair?

Hulbert wrote that he had followed Davitt’s career “with lively personal interest” since they met during the Irishman’s first visit to America in 1878. Davitt had just received his “ticket of leave,” or parole, from Dartmoor Prison, where he had served half of a 15-year sentence for treason related to his Fenian activities. He returned to Ireland in 1879 to help found the Irish National Land League.

As editor of the New York World at the time, Hurlbert said he dispatched a correspondent to Ireland to interview Davitt. He quoted Davitt from the nine-year-old interview as saying “the only issue upon which Home Rulers, Nationalists, Obstructionists, and each and every shade of opinion existing in Ireland could be united was the Land Question.” (Davitt wrote at least one column about the Land League for the New York World, on 4 June 1884, a year after Hurlbert’s departure as editor due to a change in the newspaper’s ownership.[23])

Hurlbert admired Michael Davitt although he opposed his politics.

In the 1888 London interview, Hurlbert reported that Davitt, then 42, was supporting English poet and writer Wilfrid Scawen Blunt in an upcoming by-election in Deptford, England. Blunt had become a supporter of Irish nationalism a few years earlier. According to Hurlbert’s account, Blunt told Davitt that Balfour “meant to lock up and kill” the four “pivots” of the Irish movement: William O’Brien, Timothy Harrington, John Dillon and Davitt.

“How did you take it?” Hurlbert asked.

“Oh, I only laughed, and told him it would take more than Mr. Balfour to kill me, at any rate by putting me in prison,” Davitt replied. “As for being locked up, I prefer Cunninghame Graham‘s way of taking it, that he meant ‘to beat the record on oakum.’ ”[24]

Graham was a journalist, socialist and Scottish nationalist MP who spent six weeks in prison for participating in the November 1887 Trafalgar Square Riots against unemployment and coercion in Ireland. He reportedly displayed great stoicism while incarcerated and refused to accept special privileges.

As for oakum, the hard labor of unraveling old ropes was a common punishment in Victorian prisons. It was work Davitt had done during his long days in Dartmoor, despite having lost one arm in an industrial accident at age 11.

Blunt lost the by-election two weeks after Davitt’s interview with Hurlbert. In his own book about the Land War period in Ireland, published in 1912, Blunt recalled his first meeting with Davitt in 1886 at the Imperial Hotel in Dublin. He described the Mayo native as “a most superior man, with more of the true patriot about him than any of those I have yet met.”[25]

Hurlbert also praised Davitt:

“If all the Irish ‘leaders’ were made of the same stuff with Mr. Davitt, the day of a great Democratic revolution [in Ireland] … might be a good deal nearer than anything in the signs of the times now show it to be. … I have always regarded him as the soul of the Irish agitation, of the war against ‘landlordism’ … and of the movement towards Irish independence. Whether agitation, the war, and the movement have gone entirely in accordance with his views and wishes is quite another matter. … [But] he has never made revenge and retaliation upon England either the inspiration or the aim of his revolutionary policy.”[26]

OTHER ISSUES

Hulbert recognized that Davitt was not going to divulge to him the latest strategies of the Irish agrarian and nationalist movements. “I could neither ask, nor, if I asked, could expect to get from him,” he wrote.[27] Based on the five pages Hurlbert devoted to his one-hour interview with Davitt, it appears the American journalist focused his questions on other issues.

Hurlbert reported that Davitt’s thoughts were occupied with managing a wool export business, which the author believed could penetrate the American markets despite a tariff at the time. “He has gone into it with all his usual earnestness and ability,” Hurlbert wrote of Davitt. “This is not a matter of politics with him, but of patriotism and of business. He tells me he has already secured very large orders from the United States.”[28]

The day before meeting with Hurlbert in London, Davitt wrote in his diary: “Attended Woolen Co. meeting. While doing fairly well in America, orders not as large as expected though. Visit was another loss for season.”[29]

The Irish Woolen Manufacturing & Export Company was established in spring 1887 with backing from about 20 Dublin business men. Davitt told the Freeman’s Journal that the enterprise would buy wool from small mills, pay owners on delivery of orders, “and in that way increase their confidence and help them to extend their works, improve the workmanship of their goods, and gradually multiply their hands.”

Hurlbert also suggested that Davitt was “quite awake” to the possibility of developing granite quarries in counties Donegal and in his native Mayo. “This bent of his mind towards the material improvement of the condition of the Irish people, and the development of the resources of Ireland, is not only a mark of his superiority to the rank and file of Irish politicians–it goes far to explain the stronger hold which he undoubtedly has on the people of Ireland.”[30]

The American reporter recognized Davitt’s interest in cultivating native industries. Davitt wrote a series of articles between November 1885 and January 1886 for the Dublin Evening Telegraph that “advanced practical proposals on industrial rejuvenation at a time when Dublin industries were moribund,” historian Laurence Marley has noted. Marley continued:

“Davitt had spoken of the need for Irish industrial development after his release from Dartmoor [prison]. … He undertook a number of industrial ventures, incurring considerable financial costs. His practical interventions met with little success, but the ideas which he expounded were nevertheless significant.[31]

DAVITT RESPONDS

Davitt did not mention his interview with Hurlbert in his diary, which includes such mundane notations as “Sick” and “At home gardening all day” and “Wrote 25 letters since 8 last night.”[32] He did pay attention to other press coverage, including of his 29 January 1888, speech in Rathkeale, the one noted by Hurlbert upon his arrival in Ireland. In his next day entry, Davitt wrote:

“Splendid report in yesterday’s London Times of my Rathkeale speech. Freeman[’s Journal] had left out references to boycotting etc. Times leader strangely complimentary–which means, if it has any meaning–put this man in Tullamore.”

Within weeks of Ireland Under Coercion’s publication, Davitt blasted Hurlbert’s book as “a plagiarised, but venomous attack upon the Nationalists of Ireland.” In the 9 September 1888, speech at Knockaroo, Queens County (now Laois), Davitt suggested that four years earlier Hurlbert had tried to secure the U.S. ambassadorship in London through some of Parnell’s friends in America. When that didn’t happen, Hurlbert turned on Parnell and Irish nationalists.[33]

Davitt blasted Hurlbert’s book as “a plagiarised, but venomous attack upon the Nationalists of Ireland.”

Ireland Under Coercion was “stale abuse of Mr. Parnell and Home Rule, in praise of Mr. Balfour and the Irish landlords,” Davitt said. “English society’s hatred of us will even go so far as to adopt an American adventurer when he qualifies for its salons.”

In his October 1889 testimony before the Special Commission on “Parnellism and Crime,” Davitt made a passing reference to Hurlbert as having attended a July 1882 speech he gave in New York City. He described the American journalist as “at the time editor of a New York newspaper, now Coercionist chronicler for Mr. Balfour in Ireland.”[34]

In his 1904 book, The fall of feudalism in Ireland, Davitt again briefly mentioned Hurlbert, by then dead for nine years. Davitt seemed to back off his 1888 assertion about the ambassadorship:

“Ireland Under Coercion… was intended to show that Mr. Parnell and the National League, not Mr. Balfour and Dublin Castle, were the true coercionists in Ireland. What the purpose or motive of the book was has remained a mystery.”[35]

See Mark Holan’s 2018 blog series Ireland Under Coercion, Revisited. He can be reached at [email protected].

© 2018 by Mark Holan

References

[1] William Henry Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion: The Diary of an American, (IRELAND UNDER COERCION) The Riverside Press, Cambridge, 1888, page 10. (The book was originally published in two volume, then combined into this single edition, available through the Internet Archive.)

[2] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 8.

[3] Lewis Perry Curtis, Jr., The Depiction of Eviction in Ireland 1845-1910, UCD Press, Dublin, 2011, page 130 (chapter title).

[4] Bernadette Whelan, American government in Ireland, 1790-1913: A history of the U.S. consular service, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2010, page 236.

[5] The Literary World; a Monthly Review of Current Literature, 19 January, 1889, page 22.

[6] Times of London, 18 August, 1888, page 12.

[7] United Ireland, 25 August,, 1888, (Page number missing from my notes of 22 February, 2018, microfilm review at National Library of Ireland.)

[8] Page 7 of the pamphlet, reviewed on loan from University of Notre Dame Hesburgh Libraries.

[9] W.B. Yeats, “The Irish Dramatic Movement”, Nobel Lecture, 15 December, 1923.

[10] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 405.

[11] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 80 and 103.

[12] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 38.

[13] Freeman’s Journal, 30 January, 1888, page 6

[14] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 39.

[15] Freeman’s Journal, 30 January, 1888, page 6

[16] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 45.

[17] Lewis Perry Curtis Jr., Coercion and Conciliation in Ireland, 1880-1892, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1963, page 263, citing 13 August 1888, letter from Balfour to E. Barrington.

[18] Ibid., page 408, citing 6 February, 1888, letter from Balfour to J. Roberts.

[19] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 42-43.

[20] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 10.

[21] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 60.

[22] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 159.

[23] George Juergens, Joseph Pulitzer and the New York World, Princeton University Press, New Jersey 2015, pages 258-259.

[24] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, 160-61.

[25]Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, The Land War in Ireland: Being a Personal Narrative of Events, S. Swift & Co., London, 1912, page 50.

[26] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 162.

[27] Ibid.

[28] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 159

[29] The Papers of Michael Davitt Collection, IE TCD MS 9547-52, Diaries and notebooks 1877‐1906. Reviewed by author, 21 February, 2018 at Trinity College Dublin.

[30] IRELAND UNDER COERCION, page 163.

[31] Laurence Marley, “Davitt and Irish economic development: ideas and interventions” chapter of Michael Davitt: Freelance Radical and Frondeur, Four Courts Press, 2007, pages 130 and 156-158.

[32] The Papers of Michael Davitt Collection, Trinity College Dublin.

[33]Leinster Express, 15 September 1888, page 7

[34]The Times Parnell Commission Speech Delivered by Michael Davitt in Defense of the Land League, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., London, 1890, page 152.

[35] Michael Davitt, The fall of feudalism in Ireland; or, The story of the land league revolution, Harper & Bros., London, 1904, page 559.