The Irish Girl and the American Letter: Irish immigrants in 19th Century America

By Martin Ford

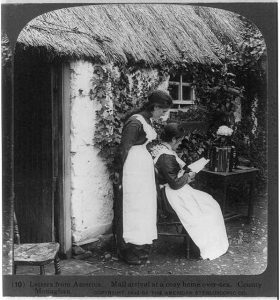

The written missive had remarkable significance for trans-Atlantic migration. Indeed, the peopling of North America owed more than a little to a letter, specifically, what was called “the American letter,” written—sometimes dictated—by millions of immigrants to their families and friends at home.

Throughout the long history of migration to the United States, the American letter played a crucial role in the lives of countless immigrants, as well as friends and family left behind.

Throughout the long history of migration to the United States, the American letter played a crucial role, especially for the Irish.

The letter home delivered news to loved ones, afforded an outlet for emotions, encouraged new migration through descriptions of the good life in America, and offered instruction on how intending immigrants might join those who had gone ahead. The American letter was the voice of experience from a strange but enticing land. The letter may also have contained cash, a bank draft or a prepaid ticket with a plea that a relation or friend follow the writer’s path to the new country.

In short, the American letter was an essential part of the migration experience for people from many countries, but for no other group was it more important than for the Irish. Between 1854 and 1875, more than 60 million letters made their way from the United States to the United Kingdom. Authorities estimate that well over half of these were destined for Ireland.[1] What has rarely been recognized is that most seem to have been written by young Irish women.

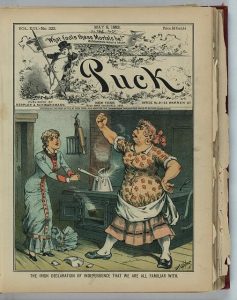

Much of Irish-American history has focused on the travails of the Irish laborer, Paddy, in building the canals, railroads and roads—essentially laying the foundation of urban America. Less has been said about how the Irish girl, Bridget, contributed mightily to Irish emigration through her work as a domestic servant and as author of the American letter, which had magnetic effects upon family and friends in Ireland.

The importance of the letter home to the Irish

Why would the trans-Atlantic letter be more important for the Irish than for other nationalities? One reason was timing. Irish immigration to America peaked in the wake of the Great Famine that devastated the old country starting with the failure of the potato crop in the autumn of 1845.

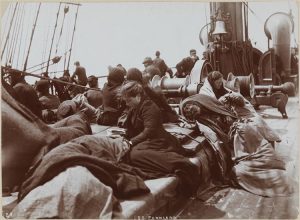

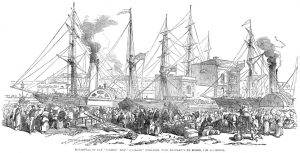

Over the next ten years, more than two million Irish fled Ireland, with at least 60 percent of them going to America. They came during the sailing era, when crossing the Atlantic took six to eight weeks, sometimes even longer. For most, the passage was irreversible, giving rise to a practice called the “American wake,” a farewell touched with tears of mourning because it was likely to be the last. The best view of Ireland, the saying went, was from the back of a departing ship, and most of those who departed would never see the Irish coast again.

This irreversible crossing was not the case for immigrants who would come to America from other countries in later decades. By the 1880s, the steamship had become the dominant mode of transport, reducing the Atlantic voyage to two weeks or less. The steamer also decreased the cost and eased the hardship of passage, ushering in the so-called Great Wave of immigration (1880-1924) when many of the immigrants were “birds of passage,” men who came and went as migratory laborers.

While about half of Italian immigrants to America in the 19th century returned, the vast majority of Irish never went went home.

Demographers estimate that some 50 percent of Italians went back to their home country.[2] By contrast, only 5 to 10 percent of Irish immigrants ever returned home.[3] The Irish were permanent. If absence makes the heart grow fonder, then permanent absence nurtured among the exiles of Erin a profound longing for the old country expressed in countless ballads and poems. It also nurtured a formidable correspondence between America and Ireland.

A second reason the American letter had such significance for the Irish was that the average Irish immigrant could read and write. Although they generally came from poor farming families, many had the rudiments of literacy, especially in comparison to immigrants from the continent. In Ireland, both the traditional “hedge schools” and the National Schools, which opened in 1831, emphasized literacy. During the nineteenth century, the percentage of Irish with basic skills in reading and writing rose from around 30 percent in the 1830s to 75 percent by mid-century, culminating in a rate of 97 percent in 1900, higher than for the general American population.[4] These averages tended to be highest among the young, and most immigrants were young.

The third reason for the prominence of the letter home was the unusually high percentage of women among Irish emigrants, especially young, single women. While men may have formed the emigration vanguard during the height of the Famine exodus, women, most younger than twenty-five and many in their teens, represented a larger portion of migrants than for any other national group. [5]

In some decades, Irish female immigrants outnumbered males. On the eve of the American Civil War, for example, women made-up half of all foreign-born Irish, a share that was to increase as the century wore on in what historians have called “the feminization” of the Irish diaspora. [6] This modest imbalance in favor of women, combined with the occupational circumstances of both sexes, helped ensure that women would be responsible for a large share of Irish letters from America.

Irish women in 19th century America

One of the ironies of nineteenth-century Irish immigration was that, on coming to America, the almost wholly rural Irish—scorned as “dirt diggers” and “bog trotters”—became city dwellers. Together with German newcomers, the Irish dominated immigrant arrivals through much of the nineteenth century. By 1870, the two groups represented a full 70 percent of the foreign-born population. [7]

Unlike the Germans, who favored farming and dispersed into the nation’s heartland, the Irish clustered on the eastern seaboard, where they made up at least a quarter of the population in New York and Boston. Although the men abandoned farming, they did not relinquish the spade.

Irish women were the main source of letters home.

They quickly took up back-breaking physical labor. In 1837, the North American Review observed that American laborers resented the Irish because they “do more work for less money.” [8] Like today’s Mexicans, the Irish took jobs native-born workers did not want. By the 1850s, they had constructed the great majority of the America’s public works, doing the bulk of the labor on the young nation’s canals, roads and rail lines.

Despite the obvious value of the Irishman’s brawn, Irish women found jobs even more readily than did Irish men. “The demand for females appears to be everywhere greater and more uniform than that for males,” wrote the Anglo-Irish philanthropist, Vere Foster, in 1855. [9] By far the most important source of employment for Irish women was domestic service, most commonly as the “maid-of-all-work” in the households of America’s burgeoning gentry. As early as 1860, more than three-quarters of working Irish women were employed as domestics, a share that would vary little through the end of the century. [10]

Employers would have preferred to hire American girls. “Help Wanted” notices routinely stipulated preference for Protestant or American candidates. Complaints about “the raw Irish girl” and jokes about Hibernian ineptitude were staples of women’s publications. But for American girls, particularly those in the cities, domestic service bore a social stigma. They considered the work profoundly demeaning, preferring jobs as shop girls, mill hands, seamstresses and the like. Most any other form of work would do, even though it paid less and offered fewer opportunities to save.

The ‘awful lonesomeness’ of domestic service

As for girls from other countries, few came unattached to husband or family, and cultural proscriptions discouraged them from living in strangers’ households. During the American Civil War, a travel writer observed, “vast numbers of Irish girls had found employment as servants in families.” [11]

The numbers were indeed vast, particularly in the largest cities. In New York, Irish-born accounted for 23,386, or 80 percent of the city’s 29,470 domestics in 1855.[12] While no other city compared, by the end of the nineteenth century, 703,346 women of Irish stock—immigrants and their children—worked as domestics nationally, which was just under 50 percent of the total. [13]

The contrasting opportunities available to Irish men and women led to markedly different working lives. The physical hardships of the Irish pick-and-shovel man have become part of American lore. The hours were long, the work backbreaking, the dangers from accident and disease many.

Vast numbers of Irish girls found employment as servants in families, often enduring terrible loneliness.

As the male Irish laborer was risking his life, the Irish housemaid was working a grueling schedule, one that required, according to an expert of the time, “the temperament of a saint and the constitution of a cowboy.” [14] If she were the only servant in the household, as was commonly the case, she would be first to rise every morning to light the fires and last to bed at night, fires banked and household set in order. She typically worked six days a week and was on call through the night. She had two half-days off—Sunday afternoon and Thursday evening.

Her labor may not have been dangerous, and her surroundings were certainly more genteel, but the work was physically demanding. Virginia Penny, nineteenth-century America’s foremost authority on women in the economy, put it concisely, “Most maids of all work are Irish because most Irish can perform hard work.” [15] Even in a household where the mistress deigned to cook, an Irish girl was often retained for the heaviest labor. Sleeping in an alcove, a small room in the attic or off the kitchen, the maid had little privacy. Still, “living in” provided advantages to the unattached Irish girl far from home.

Her wages may have been meager, usually less than $4.00 a week, but her employer provided food, lodging, and a uniform, so her expenses were few. Domestic service offered opportunities to economize that were rarely available in other jobs. Indeed, many Irish girls said that this was what drew them to the work.

If the ability to put aside her earnings was for the Irish female the job’s chief attraction, then its major drawback was what one maid referred to as “the awful lonesomeness.” Writing in 1887, social reformer Helen Campbell evoked this feeling from a young Irish girl who had abandoned domestic work after only a year:

Ladies wonder how their girls can complain of loneliness in a house full of people, but oh! it is the worst kind of loneliness — their share is but the work of the house, they do not share in the pleasures and delights of a home. One must remember that there is a difference between a house, a place of shelter, and a home, the place where all your affections are centered. [16]

In The Servant Girl Question (1881), an extended reflection on the relationship between mistress and maid, the popular essayist, novelist and poet, Harriet Spofford, depicted the Irish domestic as a Cinderella without a fairy godmother. [17] She expressed admiration for the young women who toiled from dawn till dead of night amid cheerful, carefree family life from which they were usually excluded. This exclusion was part of an emerging social protocol.

In the years following the American Civil War, Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe became a Martha Stewart-like figure to American homemakers. She collaborated with her sister on an influential series of domestic guides, which urged the American mistress to keep a proper distance from the Irish servant.

Employment agency staff who placed Irish domestics in American households made a point of warning the girls not to expect to become a part of the family. One popular feminist writer of the day expressed her disbelief that any “intelligent American woman should be willing to consort with low and ignorant foreigners” in the first place. [18] Is it any surprise then that the Irish girl would strive to recreate in America the home life she had in Ireland?

And so, while Irish men worked in labor gangs apart from town life, their female kin toiled amid genteel, if sometimes chilly, domesticity. Both Bridget and Paddy must have experienced a sense of social isolation that would prompt the urge to write home. How men found the time, energy or conditions under which to write is difficult to imagine. It is easier to envision the Irish girl alone in her room at the end of the day putting pen to paper before turning to bed. By most accounts, she was a more prolific correspondent than her male kin.

The Irish women’s letter home

What can we say about the letters they wrote? The first thing to note is their sheer volume. As early as the 1830s, the Irish of New York alone were sending through Liverpool 300,000 letters per year.[19] This was eleven times the number they received in return. When the Famine struck, the numbers rose dramatically.

An American missionary touring the Irish countryside in 1847 observed the “utter astonishment of the postmasters” in handling the huge flow of incoming mail. [20] By 1854, the United States Postmaster General estimated that more than 2 million letters had been sent to the United Kingdom that year, the bulk of them to Ireland. Twenty years later, the figure had climbed to more than 6 million per year! [21]

The Irish of New York alone would send home over 300,000 letters a year.

As for the messages the letters bore, many expressed a nostalgia for the life left behind. Letters also reflected deep concern for those who remained at home, a concern expressed tangibly through remittances. By mid-century, the Irish journalist and politician, John F. Maguire, would claim that, “the great ambition of the Irish girl is to send ‘something’ to her people as soon as possible after she has landed in America…” [22]

That something, of course, was money. Indeed, the Irish at home often said that what was in the letter was more important than what it said. The terms “money letter,” “American letter” and “Yankee letter” were virtually synonymous. The Irish-born New England essayist, Henry Giles, observed in an antique turn of phrase that “the mails come burdened with rudely-directed letters…, and all the many contain remittances.” [23]

‘It is we who are really paying the rents over there!’

If “all the many” remittances did not come from women, then most did. While men included money with their letters, women were singled out for contributing what one historian called “the lioness’ share” of money sent home, a portion estimated at 80 percent in 1861.[24] No wonder then that one Protestant head of a Massachusetts household lamented what he considered the inflated wage he paid his Irish help and complained, “It is really we who are paying the rents over there!” [25]

He was not far wrong. Through what could be squeezed from earnings, the immigrant helped family pay rent, buy food, supplement a sister’s dowry, support a brother’s education and otherwise assist cash-strapped loved ones.

But rather than simply sustain kin in the old country, many young women sought to reunite with family in America. Writing about nineteenth-century Irish domestics, Hasia Diner cites “sibling solidarity” as a powerful motivation in reuniting families, noting, “It was as though Irish migrants sought to re-create what they felt were the best and most meaningful elements of their childhood families.” [26]

Remittances or money sent from America helped to stave off eviction and destitution in Ireland.

For some immigrant groups, family migration was the norm. The Germans, for example, came to America in varied combinations—as intact families, church congregations, even entire villages in colonization schemes. The Irish were too poor for such collective movement. They came as families primarily when “assisted,” especially during the worst of the Famine, when landlords paid passage for tenants, evicting them en masse as the Marquis of Lansdowne had done his tenants, so that the land they occupied might more easily be converted to pasture.

After the Famine, the Irish tended to come in ones and twos, pioneering what is today called “chain migration,” the tendency of immigrants to follow family, friends and neighbors to a new home. Yet, the Irish did not so much follow kin as they “brought them out.” In fact, to “bring out” or to “bring over” was the term used to describe the process of emigration, even in Ireland, indicating a curiously American point of view, understandable when we recognize that much of the impetus for the post-Famine exodus, especially the wherewithal, came from the Americas.

Even before the Famine, anecdotal murmurings about this unexpected wherewithal had begun to circulate among clerks and shipping agents in the banks and mercantile houses of New York, Boston and Philadelphia. In 1838, the Irish-American publisher Mathew Carey declared, “Cases have fallen under my observation of Irish female domestics, earning a dollar and a quarter per week, yet saving enough to pay the passages of brothers and sisters, one after another, in succession.” [27] Ever the proud Hibernian, Carey was thrilled by these reports, but he may also have felt a twinge of embarrassment.

Only five years earlier, he had been chiding wealthy Americans for their indifference towards the working poor, most of them Irish. He had argued that the immigrants could hardly survive on the wages they earned. How could these same impoverished Irish now be sending home, in his own words, “an incredible amount of money”? [28] In his advocate’s zeal, had Carey exaggerated the plight of the working poor?

It was only natural that the intellectual Carey would dig deeper than the apocryphal accounts crossing his desk. He began (in the fashion of a Victorian scholar) by writing letters to officials of the banks most heavily used by immigrants, sending queries to twenty-five institutions. Five responded, revealing that for the years 1835 and 1836, their depositors had sent to Ireland a total of nearly $315,000. [29]

Based on further discussions with the banks and belated returns of his survey, Carey estimated that for the two-year period remittances to Ireland had exceeded $800,000. Of course, this sum was drawn from the banks in a multitude of small drafts. So small and frequent were the withdrawals—less than twenty-five dollars was typical—that a Philadelphia banker called them “troublesome” and implied that they were hardly worth the effort.[30]

Over the next several years, evidence mounted for a massive accumulation of funds sent to Ireland in small drafts. It was not long before persons in other quarters began to note these remittances with more than mere surprise.

In 1847, Robert Murray, a Scotsman who headed the Provincial Bank of Ireland, expressed astonishment at the extent of the amounts his institution had processed the year before, the worst year of the Famine. “The remittances from Irish emigrants in America have been annually increasing for the last ten years,” Murray observed, “until they have attained their present number and amount,” which he estimated at $725,000. That amount, he concluded, was “large, powerfully large,” the equivalent of $21 million in today’s dollars. [31] “Powerfully large” seems to have been the understatement of an unsentimental Scotsman. Other commentators were more effusive, describing the aggregate transfers as “phenomenal,” “breathtaking” and “amazing”.

How did the significance of these transfers escape official notice for so long? Perhaps it was that the withdrawals were so small and that they were made by the most unprepossessing of customers, “chiefly by ‘girls in place’,” according to journalist John Francis Maguire writing in 1868. [32]

Bank clerks were sure to have remarked upon the increased traffic in December and March, for it was around Christmas and Easter that the Catholic Irish were most intent on sending money home. It was then that their letters came in droves. Staff must have struggled to understand the thick brogues of the greenhorns. They must also have struggled under the tedium of drawing up so many small drafts. Yet, would even the most insightful clerk have understood that these petty transactions were adding up to prodigious sums?

Only at a higher level, in the counting room when tallies were made at the end of the day or weekly sales calculated, would some sharp-eyed accountant have noticed and remarked on the impressive amounts being transferred to Ireland. That these amounts came from poor Irish, especially poor Irish women, may account for the delayed reaction. After all, saving money was not considered an Irish virtue. Yet, as the sums sent to Ireland make clear, saving was a virtue for many immigrants, even among the poorest.

In 1849, Earl Gray, Great Britain’s Secretary of War and the Colonies, requested an accounting of the remittances for the previous year. Thereafter, the British Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners systematically gathered this information and published annual estimates of the sums coming from North America. The yearly totals continued to climb, from $2.3 million in 1848 to $8.7 million in 1854, a peak year for Famine emigration. [33] Throughout the remainder of the 1850s, even as the worst effects of the Famine eased, the American letter remained the major source of support for the Irish poor.

All in all, the saying in Ireland that women could be “great hoarders of small coins” also applied in America. [34] Rather than secreting coins in the thatch, as was their habit in the old country, women banked their meager earnings until they could send them to relatives and friends along with entreaties that others hasten to join them.

Chain migration

If money in the American letter was an eloquent argument for emigration, the enclosure of a prepaid ticket was even more persuasive. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, more than 40 percent of all remittances came in the form of prepaid tickets, and “American money” would pay for three-quarters of all Irish emigration. Historians have observed that the millions that poured into Ireland came primarily from single women. [35]

Once married, these women tended to send less home. And yet, the Irish were noted for delaying marriage or forgoing it altogether. By the time they were ready to marry, many had fulfilled obligations to kin at home and taken on new responsibilities to husbands and children in America. They had been joined by family, who would shoulder the now shared burden of remittances home. Of those who remained single—and their numbers were large—many continued to “bring out” kin.

It was precisely this expansive sense of family feeling that kept in motion the stream of immigrants that swept America’s shores and the tide of remittances that flowed back to Ireland. Although remittances would drop during the American Civil War years (1861-65) when immigration briefly faltered, they would pick up again after the United States and Great Britain enacted an international money order convention in 1871, ensuring that money transfers would remain a driving force for immigration through the rest of the century.

Remittances also financed ‘chain migration’ from Ireland to America.

When Ireland suffered a new period of agricultural crisis in1880, the habit of emigration had become part of the national ethos. Departures were fewer than in the years immediately after the Great Famine because the suffering was less, but Ireland was a much smaller country—its population having dropped from a pre-Famine high of 8.5 million to 4.4 million by century’s end. Nearly 3 million had departed, most for North America. Ireland’s rate of emigration was higher than for any other country in Europe. [36]

Historian Dennis Clark characterized the remittances that financed so much of this immigration as, “the greatest transatlantic philanthropy of the nineteenth century.” [37] In strict monetary terms, the sums were truly remarkable. From the Great Famine through the end of the nineteenth century, known transfers exceeded $260 million, the equivalent of almost $8 billion today. [38] This figure was greater than Irish government relief for the period. It also dwarfed the sums sent home by Germans, the largest immigrant group of the time. In some years, the figure even exceeded the annual budget of the United States Navy, as one immigration critic complained. [39]

Remittances did much to relieve poverty in Ireland, mostly by paying rents, debts and taxes, but their greatest impact was upon migration itself. The Irish said, “Emigration begets emigration.” Their system of “one bringing another” had become self-perpetuating, as the pioneering migrant was joined by a sister, brother or other close relative, who then took a job and chipped in, the family working as a team to pool savings and send for cousins, in-laws and friends.

In this way, many poor Irish girls became anchors in chains of migrants that would ground Irish-American neighborhoods, parishes and political wards, institutions that helped ensure a safe landing for new arrivals.

No other country’s emigrants included so large a share of women, but the pivotal role the Irish girl played in building the Irish-American community has been overshadowed by the labors of her kinsman, Paddy who dug the canals, laid the tracks, and carried the vote. Bridget, the maid-of-all-work and brunt of Yankee humor, has yet to be fully recognized for her outsized contribution to Irish immigration.

Ever mindful of the kin from whom she departed, with a discipline and frugality which was near Calvinist in nature, the lowly Irish domestic sought both to support family in the old country and to make for them a new home in America. If emigration from Ireland was an Exodus, as native-born Americans often called it, then Bridget was its Moses. Moses directed his people with a staff, Bridget led hers with a pen.

Dedicated to the memory of Annie Malone Walsh of County Carlow and Fort Lee. I thank Donald Wright, Peggy Partello and Donald Chu for reading drafts of this essay and providing constructive criticism.

References

[1] Arnold Schrier, Ireland and the American Emigration, 1850-1900 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1958), 162.

[2] Massimo Livi-Bacci, A Concise History of World Population (Oxford, 1997), 136. Mark Wyman estimates that from one-quarter to one-third of all European migrants to the United States returned home permanently for the period 1880-1930 (Round Trip to America Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993), 6.

[3] Irial Glynn, “Emigration Across the Atlantic: Irish, Italians and Swedes Compared, 1800–1950,” European History Online, Institute of European History, June 6, 2011. http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/economic-migration/irial-glynn-emigration-across-the-atlantic-irish-italians-and-swedes-compared-1800-1950; Kerby Miller, Emigrants and Exiles (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 426.

[4] Liam Kennedy et al. Mapping the Great Irish Famine (Dublin, 1999), 94-98; Schrier, Ireland and American Immigration, 162.

[5] In the second half of the nineteenth century, nearly 70 percent of female emigrants from Ireland were 24 years-old or younger (Timothy W. Guinnane. The Vanishing Irish: Households, Migration and the Rural Economy in Ireland, 1850-1914 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 172.

[6] Hasia Diner, “Women Nineteenth-Century,” The Encyclopedia of Irish in America, ed. Michael Glazier (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999), 963; Anne O’Connell, “Take Care of the Immigrant Girls: The Migration Process of Late-Nineteenth-Century Irish Women,” Eire-Ireland, (Fall/Winter 2000): 102.

[7] Francis Amasa Walker, “American Irish and American Germans,” The Century Magazine (June 1873): 173; Richmond Mayo Smith. Immigration and Emigration (New York: Scribner’s, 1898), 67.

[8] James Boyd, “The Irish in America,” Address, Delivered before the Charitable Irish Society, Boston, March 17th, 1837, The North American Review (January 1841): 208.

[9] Vere Foster. Work and Wages, or The Penny Emigrant’s Guide to the United States and Canada (London: W. & F.G. Cash, 1855), 20.

[10] Francis Amasa Walker. “Our Domestic Service” (December 1875): 235; U.S. Senate. Report of the Immigration Commission, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1911), 71.

[11] Thomas Low Nichols. Forty Years of American Life (London,1864), 71.

[12] Robert Ernst, Immigrant Life in New York City, 1825-1863 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1994), 219.

[13] U.S. Senate. Report of Immigration Commission, vol. 28, 71-80. This percentage does not hold for the former slaveholding states, where African-Americans still dominated domestic service.

[14] Lucy Maynard Salmon. Domestic Service (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1897), 228.

[15] Virginia Penny. The Employments of Women: A Cyclopaedia of Woman’s Work (Boston: Walker, Wise & Co., 1863), 425.

[16] Helen Campbell. Prisoners of Poverty: Women Wage-Workers, Their Trades and Their Lives. (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1887), 226; Salmon, Domestic Service, 151.

[17] Harriet Prescott Spofford. The Servant Girl Question (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1881), 47-8.

[18] Gail Hamilton. Women’s Wrongs: A Counter-Irritant (Boston: Tiknor & Fields, 1868), 127.

[19] David Fitzpatrick, “Emigration:1801-1921,” The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America, ed. Michael Glazier (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999), 259.

[20] Asenath Nicholson. Annals of the Famine in Ireland, in 1847, 1848, and 1849, (New York: E. French, 1851), 69.

[21] Schrier, Ireland and American Immigration, 22.

[22] John Francis Maguire, The Irish in America (London: Longman, 1868), 315.

[23] Henry Giles. Lectures and Essays on Irish and Other Subjects (New York: D. & J. Sadler & Co., 1869), 140.

[24] Schrier, Ireland and American Immigration, 111.

[25] James Russell Lowell quoted in Salmon. Domestic Service, 63.

[26] Hasia R. Diner, Erin’s Daughters in America: Irish Immigrant Women in the Nineteenth Century (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), 16.

[27] Mathew Carey, Letters on Irish Immigrants (Philadelphia, 1838), 2.

[28] Carey, Letters, 6.

[29] Carey, Letters, 7-8.

[30] Carey, Letters, 7.

[31] William Neilson Hancock, “On the Remittances from North America by Irish Emigrants,” Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, Part XLIV, (April-November, 1873): 280. http://www.dippam.ac.uk/ied/records/53473

[32] Maguire. Irish in America, 318.[33] Schrier. Ireland and American Immigration, 167.

[34] George Potter. To the Golden Door: The Story of the Irish in Ireland and America (Boston: Little Brown, 1960), 123.

[35] Timothy J. Meagher, “The Irish,” in A Nation of Peoples: A Sourcebook on America’s Multicultural Heritage, ed. Elliot R. Barkan (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999), 281; Janet Nolan. Ourselves Alone: Women’s Emigration from Ireland, 1885-1920 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1989), 47.

[36] Glynn, Atlantic Emigration, http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/economic-migration/irial-glynn-emigration-across-the-atlantic-irish-italians-and-swedes-compared-1800-1950

[37] Quoted in Tim Pat Coogan. Wherever Green is Worn: The Story of the Irish Diaspora (New York: Palgrave, 2000), 285.

[38] Present dollar estimation made using 1860 as base date at: https://www.officialdata.org/1800-dollars-in-2018

[39] Samuel Clagett Busey. Immigration: Its Evils and Consequences (NY: DeWitt and Davenport, 1856), 65.

© 2018 Martin Ford