Robert Byrne – the IRA Volunteer and Trade Unionist whose killing sparked the “Limerick Soviet”.

By Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc

By Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc

Although there had been some skirmishes between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces in Ireland in the two years following the 1916 Rising the IRA’s ambush of two Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) Constables at Soloheadbeg, Tipperary on the 21st January 1919 is generally accepted as the military event which began the Irish War of Independence.[1]

Whilst the names [2] of the first two members of the British forces who were killed in War of Independence, and the circumstances of their shooting at Soloheadbeg are relatively well known throughout Ireland, few Irish people, including the most ardent of Irish Republicans, can identify the first member of the IRA to be shot dead subsequent to the Soloheadbeg attack.

That first Republican killed in those circumstances was a Dublin-born member of the 2nd Battalion of the IRA’s Mid-Limerick Brigade named Robert “Bobby” Byrne and his death triggered “The General Strike against British Militarism” more commonly dubbed “The Limerick Soviet”.

Bobby Byrne

Robert Byrne was one of nine children born to Robert Byrne and Annie Hurley. The family were originally from Dublin but had moved to Town Wall Cottage, near St John’s Hospital in Limerick shortly after Roberts birth in 1889.

Following the widespread political and social upheaval in the wake of the 1913 Lockout and the 1916 Rising Byrne became a very ardent Trade Unionist and this soon brought him to the notice of the Post Office authorities.

About the same time he also joined the IRA and this in turn brought him to the attention of the RIC. In late 1918 Byrne was called before his senior management at the Post Office where a number of charges were laid against him. Byrne mounted a very stout defense of his actions but nonetheless he was dismissed from his job for political activity and sedition.[3]

Robert Byrne was arrested and imprisoned for possession of a revolver and ammunition and faced with military court martial.

On the same date that the Irish War of Independence began with the Soloheadbeg Ambush and the historic inaugural meeting of Dáil Éireann, Byrne was a prisoner of the British Army facing court-martial in the New Barracks, Limerick. Byrne was charged with possession of a revolver, ammunition and a pair of binoculars were said to have been discovered by the RIC at his family home.

He refused to recognize the right of British Army officers to try Irish citizens in Ireland and as a protest against the court-martial, he refused to enter a plea or take part in the proceedings. Unsurprisingly the three British Army officers who made up the court found Byrne guilty and he was sentenced to 12 months in jail with hard labour. Immediately afterwards Byrne was transferred to Limerick Prison to serve his sentence.

Shortly afterwards Byrne and sixteen other republican political prisoners, who were held in the jail, began a campaign demanding political status. When this was refused Byrne helped to lead a prison protest which saw the prisoners barricading themselves in their cells, destroying prison furniture and singing republican songs.

They sang so loudly that a crowd of onlookers and supporters began to gather outside the prison. In reprisal the Prison Authorities called in the RIC to ‘restore order’ by batoning the prisoners into submission. Byrne and his fellow prisoners had their footwear confiscated and were punished with solitary confinement. In February 1919 the prisoners feeling that they had no option left went on hunger strike.[4]

The condition of the prisoners, especially Robert Byrne, was giving the British Government serious cause for concern and Byrne was transferred under armed guard to the Union Workhouse hospital on the evening of Wednesday 12th March 1919. Byrne’s round-the-clock six strong guard consisted of one prison officer; Warder Pat O’Mahony, in addition to four RIC Constables; Constable Martin O’Brien, Constable James Tierney, Constable James Spillane and Constable John Fitzpatrick all of whom were under the command of RIC Sergeant Henry Goulden.

The transfer of Byrne, to the Union Hospital had presented an opportunity to the IRA to rescue their comrade.

A fatal rescue attempt

One factor that the prison authorities had overlooked and that was to be crucial to a rescue attempt was the fact that Byrne was actually held under guard in a public ward in full view of visitors to the hospital. The IRA plan was that the volunteers would enter the ward posing as visitors to the various patients and at a given signal, they would hold up and overpower the police guard.

Byrne would then be taken by a waiting car to Benson’s Nursing Home at The Crescent, Limerick where he would receive medical care before going into hiding at an IRA safe house in the city.

Twenty IRA Volunteers attempted to rescue Byrne from police custody, leading to the fatal shooting of three men – Byrne and two RIC constables.

Twenty IRA Volunteers took part in the rescue operation and these were divided into two sections – the was first under the command of Jack Gallagher of Bishop Street, Limerick and the second was under the command of a railway engineer by the name of Michael ‘Batty’ Stack. These two section leaders were the only armed IRA participants in the attack. Only the section leaders were to be armed.[5]

The rescue attempt began when Stack visited Byrne in the ward and let him know what was planned. When Byrne was appraised of what was afoot Stack left the ward by a side door and instructed the men under his command to enter the ward posing as visitors to the various inmates. When all the volunteers were in place Stack blew his whistle and on this signal, the unarmed IRA Volunteers posing as visitors in the ward immediately sprang into action and raced towards Byrne’s bed to overpower and disarm his RIC guard.[6]

All was going to plan until Constable James Spillane the RIC Constable realised what was happening and threw himself on top of the Byrne who was lying in bed. Rather than let Byrne escape Constable Spillane drew his .45 Webley & Scott revolver, pointed it at Byrne and fired it into his chest from just a few inches away.

When Stack saw Constable Spillane’s attack on Byrne, he drew his revolver and shot the policeman in the back wounding him.

Members of the rescue party lifted Byrne from the bed and assisted him out of the ward. At this stage all the RIC Constables and the prison Warder had been overpowered, disarmed, bound and gagged except for Constable Martin O’Brien, who managed to free himself and was about to open fire on the rescue party when Stack again opened fire, shooting O’Brien dead. The shooting caused a major panic as patients, staff and visitors alike, rushed in all directions seeking shelter.

When Byrne and his rescuers reached the front of the hospital there was no sign of the ‘get away’ car they had organised to spirit Byrne to safety. The original car driver had been called away to another IRA operation and the replacement driver had not been fully briefed on the details of the plan and had driven the car to the rear entrance of the hospital rather than the main entrance where Byrne and his rescuers were waiting.

When the IRA Volunteers realized that the car to take Byrne from the scene was not where they had expected they had to abandon plans for his removal to a Nursing Home in Limerick. Instead they fled on foot it was only at this stage those assisting Byrne to escape noticed that he had been badly wounded and was bleeding heavily.[7]

They stopped the first pony and trap that they met at Hasset’s Cross. The occupants of the trap were John Ryan of Knockalisheen and his wife Margaret. Byrne was placed in the trap and taken to Ryan’s house at Knockalisheen just outside the city in the parish of Meelick, County Clare. The distance from the Workhouse to Ryan’s farm house in Clare was a mile and three quarters away. When the party reached Ryan’s, Byrne was immediately put to bed and medical and clerical aid was sent for.

Upon examination it was found that Byrne had a large bullet wound on the left side of his body and the bullet had perforated his lung and the abdomen. Unfortunately Robert Byrne was beyond human help and he succumbed to his wounds at 8.30 o’clock that evening despite the best efforts of Doctor John Holmes.

‘A Special Military Area’

After the rescue most of the rescuers had scattered back to the city and only just in time as the police and military launched a huge search as news of the rescue became known.

When eventually the remains of the twenty-eight year old, former postal clerk, were discovered all those in attendance were immediately arrested and a number of houses in the immediate area were raided. Mrs Annie Byrne, the mother of Robert, was also among the people arrested and taken in for questioning.

In total five men, Sean Hurley, Thomas Crowe, Michael Doherty, Arthur Johnson and Martin Bray were imprisoned on a charge of being accessories in the murder of Constable O’Brien.

None of the five men had either hand act or part in the attempted rescue or the shooting of the policeman. Their real crime was to have been in Ryan’s house when it was raided or to have been related to Robert Byrne[8]. A measure of the temper of Limerick City on that Monday Evening was that when the prisoners were being taken into William Street Barracks a large crowd had gathered who cheered the prisoners and jeered the police. The newspaper accounts state that the police baton charged the crowd and a number of people were injured.

On the Monday after Byrne’s death a proclamation had been issued in Dublin Castle as follows,

‘In consequence of the attack by armed men on police constables and the brutal murder of one of them at Limerick yesterday, the government has decided to proclaim the district as a special military area’.

Whilst the decision to proclaim the city had been taken on Monday April 7th it was felt that it would be better to hold off the implementation until the funeral of Robert Byrne was over.

Inquest

On Tuesday morning the Coroner for East Clare[9], Michael Brady, opened an inquest into the death of Robert Byrne. The inquest was held at Ryan’s house in Knockalisheen. Hemorrhage, peritonitis and shock were listed as the causes of death.

Dr Humphreys in his evidence stated that the bullet that caused Byrne’s death had entered the body just below the left nipple. Dr Humphreys, was also of the opinion that the bullet was fired in a downward direction and because of the scorch marks on the nightshirt it was fired from exceptionally close range.

The inquest found that Robert Byrne had been shot dead at point blank range.

When the line of evidence was beginning to point strongly in the direction of one of the police guard as having fired the fatal shot, the RIC District Inspector objected to Dr Humphreys giving evidence as it was ‘going beyond the lines of expert knowledge’ and at that point the RIC successfully applied for the inquiry to be adjourned.[10]

How Byrne came to receive the wound has often been a source of some controversy. The view of the rescuers was that Constable Spillane had deliberately shot the prisoner when he threw himself on top of him in the hospital ward. This was also the version of events that Byrne himself related to Doctor John Holmes shortly before he died.

At the inquest into Byrne death Mr Thomas Gaffney, the Crown Solicitor, stated that the bullet that killed Byrne did not come from a police revolver. It would appear that this statement was a deliberate muddying of the waters by the authorities especially in light of the fact that Dr Humphreys assisted by Dr. Brennan, who carried out the post mortem on Byrne, stated in cross-examination at the inquest, that he did not find the bullet.

Further evidence at the inquest established that the night shirt worn by Robert Byrne had scorch or black marks near the bullet hole which indicated that the bullet was fired from almost point blank range. However some credence was lent to the possibility of Byrne having been accidentally wounded by Batty Stack when Stack admitted in an interview, in later years, to the Limerick TD and history enthusiast Jim Kemmy that it was possible that he wounded Byrne.[11]

However what is very clear is that Byrne, who knew that he was dying when he made his statement to John Holmes, had nothing to gain by blaming Spillane if Spillane was not the culprit.

This statement is corroborated by the evidence tendered at the inquest, by Dr Humphreys and the statement of Gaffney does not stand up. The most damning evidence surely was the black powder marks on the night shirt. These could only be caused by a bullet fired at virtually point blank range. While it may well be that Batty Stack fired wildly the shooting of Byrne was in accordance with RIC policy that prisoners were to be shot rather than allow them escape.

Funerals

In death Robert Byrne suffered one last indignity from the authorities as his IRA uniform had been removed and despite protests by mourners it was not returned. On the evening of Tuesday April 8th the remains of Robert Byrne, Trade Union activist and Irish Volunteer, were removed from Ryan’s to St John’s Cathedral.

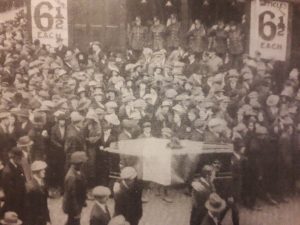

Huge crowds lined the five-mile route from Knockalisheen as the hearse with the coffin draped in the tri-colour passed on its way. Throughout Wednesday April 9th Byrne’s remains lay in state in front of the high altar in St John’s Cathedral. Thousands of people from Limerick City and beyond came to pay their respects.

By contrast the removal and burial of Constable Martin O’Brien was a much more muted affair. His remains were removed from Limerick on Monday evening to the parish church at Birr in County Offaly. He was buried on Tuesday following Requiem Mass. The Limerick Chronicle only makes mention of one brother and one plainclothes RIC Constable travelling with the remains from Limerick to Birr.

The funeral of Robert Byrne was held from St John’s Cathedral on Thursday April 10th to Mount St Lawrence’s Cemetery. By any measure the cortege was reckoned to be the largest that passed through Limerick for many years. The interment took place amidst huge crowds of sympathisers and police. The route of the funeral had effectively taken the cortege through the centre of the city and all business premises, along the route, were closed as a mark of respect. As Byrne’s coffin was passing up William Street a group of four British Army soldiers in uniform were captured on film standing to attention and saluting.

The ‘Limerick Soviet’

Even as the funerals of Byrne and O’Brien were taking place the British Military had begun to enact their plan for the city. On Wednesday April 10th Brigadier General C J Griffin the O/C of the Limerick area formally declared Limerick City to be ‘a special military area’. This meant that all civilians had to apply for and carry a special military permit to travel.

In protest at the British military declaration of a special military area, the Limerick Trades Council declared a general strike that was dubbed the ‘Limerick Soviet’.

In response the Trades Union Council, of which Byrne had been a leading member, called a ‘General Strike against British Militarism’ which lasted for a fortnight. That strike was dubbed “The Limerick Soviet” by several foreign press correspondents who coincidentally were in Limerick at the time to report on the adventures of an unfortunate British pilot and adventurer named Woods, who ultimately never managed to reach Limerick let alone America![12]

The General Strike lasted from the 14th to the 27th April 1919 when it was called off by the Strike Committee after the local Catholic Bishop Denis Hallinan and the Mayor of Limerick Alphonsus O’Mara brokered a resolution to the dispute whereby workers would apply to their employers for a permit to enter the special military area rather than applying directly to the British Army for their permits – thus ending the dispute.

Whilst the so-called “Limerick Soviet” is still relatively well known in academic historical circles and has an enduring popularity amongst political activists on the left-wing of Irish politics; Robert Byrne’s the man whose death sparked the strike is largely forgotten.

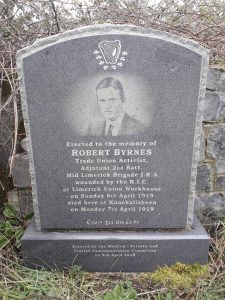

On Easter Sunday 2015 the Meelick-Parteen and Cratloe War of Independence Commemoration Committee erected a monument at the site in Knockalisheen, Meelick, County Clare where Robert Byrne died, and to mark the centenary of Byrne’s death the Committee has organised a commemoration at the Robert Byrne Monument at 2pm on Saturday 6th April 2019 – all are welcome to attend.

References

[1] It is arguable that the IRA raid on Eyries RIC Barracks, Cork on St. Patrick’s Day 1918 or the killing of IRA Volunteers Richard Laide and John Browne during a failed attack on Gortatlea Barracks, Kerry a month later on 13th of April 1918 could also be considered strong contenders for the beginning of the war – but the fact that the IRA shot dead two RIC Constables at Soloheadbeg on the same date as the inaugural meeting of Dáil Éireann makes the 21st of January 1921 the most convenient date for both political and scholarly purposes to date the beginning of the conflict.

[2] James McDonnell and Patrick O’Connell

[3] Tom Toomey, The War of Independence in Limerick 1912 -1921 (Limerick 2011).

[4] Tom Toomey, The War of Independence in Limerick 1912 -1921 (Limerick 2011).

[5] Among those rostered to take part in the operation were Denis Maher (Maher was later burned and seriously disfigured at the burning of Kilmurry RIC Barracks, near Castletroy, in April 1920), Tadhg Kelly (Tadhg or Thady Kelly, later joined An Garda Siochana and was posted to County Louth. He was grandfather to the Irish soccer international Gary Kelly and great grandfather to Ian Harte), Patrick Dawson, Michael Danford, Timothy Buckley, ‘Lefty’ Egan, Corky Ryan, Michael Clancy, Terry Enright, Billy Wallace, Mick Walters, William Hayes, Joseph O’Brien, Daniel Gallagher, Michael Hogan, Edward Doran, John Clancy and Joe Saunders Limerick’s Fighting Story & 2nd Batt Roll Mid Limerick Brigade Per Patrick Power.

[6] Tom Toomey, The War of Independence in Limerick 1912 -1921 (Limerick 2011).

[7] Tom Toomey, The War of Independence in Limerick 1912 -1921 (Limerick 2011).

[8] Sean (John) Hurley who was one of the founders of the Volunteers in Limerick was a cousin to Robert Byrnes. Byrne’s mother was Hurley, whose family originally came from Carrigmartin, near Ballyneety. Arthur Johnson was one of a family with a strong tradition of involvement in the Volunteers and the IRA.

[9] Although the rescue and shooting of Robert Byrnes occurred in Limerick City, the fact that he died in County Clare meant that the inquest was held in that county.

[10] Tom Toomey, The War of Independence in Limerick 1912 -1921 (Limerick 2011).

[11] Forgotten Revolution by Liam Cahill (O’Brien Press 1990).

[12] Tom Toomey, The War of Independence in Limerick 1912 -1921 (Limerick 2011). Woods was attempting to become the first man to fly the Atlantic from east to west, but Wood’s plane actually went down in the Irish Sea even before it got to Ireland