The death of Volunteer Seán Doyle: ‘A conflict of testimony’’

By Aaron Ó Maonaigh

On 19 September 1920, Seán Doyle of the 4th Battalion, Dublin Brigade’s engineering section was shot and killed when members of the Auxiliary Division Royal Irish Constabulary (A.D.R.I.C.) surrounded a party of Irish Republican Army (I.R.A.) volunteers in the Dublin Mountains.

Doyle’s death received much coverage in the daily periodicals in the week that followed his death, as such, speculation was rife as to the exact nature of what had occurred on the hills of Kilmashogue on 19 September 1920.[1]

Sean Doyle was shot dead by British forces in the Dublin Mountains on September 19, 1920.

One of the earliest reports of the event by the Irish Independent on 21 September 1920 stated that ‘the young man… was killed when 40 arrests were made by ‘armed civilians’’ on the Dublin Mountains on Sunday [19 September 1920]’.

As the days wore on speculation was rife as to whether the men arrested at Kilmashogue were armed, as the arresting military claimed, or whether they had been caught unarmed and unaware by a large party of military in mufti, as others had suggested.[2]

The Strabane Chronicle reported on 25 September that it had ‘on [the] most reliable authority’ been informed that the men arrested at Kilmashogue were not in possession of firearms or ammunition.[3]

Evidence given by the military and the police (A.D.R.I.C.) at the inquest into the death of Seán Doyle contradicted the claims of the Irish press, Sergeant William James Duffy (A.D.R.I.C.), maintained, upon questioning, that a shot was fired firstly by a member of an I.R.A. party which had approached his body of men, and thus shots were fired in return by Duffy’s party.[4]

Neither of these claims stand up to scrutiny. What follows is an examination of what actually occurred that day on the slopes of Kilmashogue.

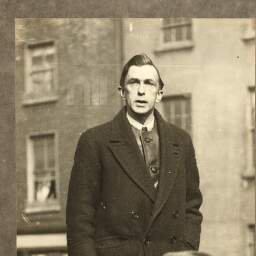

Seán Doyle

Seán Doyle was born at Inchicore, Dublin in 1901, the second of seven children born to Peadar Seán Doyle (Ó Dughaill) a member of local government (alderman) and engine fitter at the Great Southern & Western Railway (G.S. & W.R.) works, and Kathleen Doyle (née Hutton).

At an early age he joined the Inchicore sluagh of Na Fianna Éireann, which included several boys who would later join the local company of the Irish Volunteers – F Company – of the Dublin Brigade’s 4th Battalion. [5]

During the 1916 Easter Rising he acted as a dispatch carrier in the South Dublin Union area along with several fellow members of Na Fianna and was subsequently rounded up and taken to Richmond barracks, Inchicore, in the aftermath of the rebellion.

Sean Doyle served in the Fianna in 1916.

As Robert Holland, a neighbour and comrade of Doyle recalled ‘some [were] only of tender years whose fathers or elder brothers had participated’.[6] During the identification process which took place in Richmond barracks, Seán and the other young boys, including Holland’s brother Wattie, were separated from the older men, and subsequently released without charge.

Doyle’s father, Peadar, was Quartermaster General of the 4th Battalion’s F Company (Dublin I Brigade), and fought under the command of Éamonn Ceannt in the South Dublin Union during Easter week 1916; a part for which he was sentenced to penal servitude for ten years.[7]

Peadar Doyle was interned firstly at Portland and later at Lewes and Pentonville prisons before being released from Parkhurst on 17 June 1917.[8] Whilst his father’s Volunteer activities were largely curtailed after the Rising, Seán’s increased, and like many of the younger boys of the Inchicore district, he later graduated from he Fianna into a full member of the local Volunteer company.[9]

Parade at Kilmashogue?

Many of the newspaper reports concerning the death of Seán Doyle erroneously state that the Volunteers were rounded up whilst parading at Kilmashogue, however, the Bureau of Military History statement of James Tully of the 3rd Battalion’s engineering section sheds some light on the true purpose of the Volunteers’ exercise that day.

In his statement, Tully recalled that ‘on Saturday evening, 18th September, 1920, part of No. 3 Company went to camp at Kilmashogue and the rest of the Company, along with No. 4 Company, were to report on Sunday morning’, and that the ‘The party that had arrived on the Saturday went farther up the mountains to try out some explosives’.[10]

In early 1918 I.R.A. G.H.Q. began the task of establishing an engineering department, of which, Rory O’Connor was appointed director.[11] The selected men were drawn from the building and allied trades, electrical and railway workers, quarry men (for their explosives experience, and engineering students etc.[12]

The Volunteers were testing explosives at Kilmashogue, outside Dublin.

According to Liam O’Doherty ‘it was decided that each Battalion in the [Dublin] Brigade should form a single unit in their own Battalion of all the Company’s Sapper Sections, and organise it as an Engineering Company under the command of an officer’. [13]

The unit underwent further reorganisation in 1919 when it was formed into a Battalion (5th) consisting of four companies, titled ‘Nos. 1, 2, 3, & 4’ which corresponded to their respective I.R.A. battalions.[14] Seán Doyle was a member of No. 4. Section ‘General Demolitions’, which specialised in the production of homemade explosives in addition to training in the use of incendiaries.[15]

The objective of the training camp at Kilmashogue was the testing of a newly developed explosive which the Engineering Battalion O/C Liam Archer euphemistically dubbed ‘War flour’; the I.R.A. at this point of the conflict were actively engaged in the production of several types of incendiaries, with varying degrees of success.[16]

Forewarned but not forearmed

Critically, and quite negligently, the I.R.A. proceeded with the planned demonstration despite forewarning that the military were in the vicinity of the camp, occupying the nearby St. Columba’s College. Both Liam Archer and Jack Plunkett recalled the forewarning, which Archer stated came from the Rathfarnham (E Co. 4th Battalion) Company.[17]

Critically, and quite negligently, the I.R.A. proceeded with the planned demonstration despite forewarning that the military were in the vicinity of the camp

Plunkett passed on the intelligence to Rory O’Connor; however, it was decided to go ahead with the operation as planned.[18] On the Sunday morning, a number of the Engineering Battalion staff including Liam Doherty, Jack Plunkett and Liam Archer joined Mick McEvoy’s unit which had arrived at Kilmashogue Lane the previous evening.

The site that was chosen for the demonstration was one which the Engineering Battalion and Na Fianna used with some frequency; referred to locally as ‘Courtney’s Quarry’. Jack Plunkett remarked of the site on the day that ‘there was nothing unusual to be noticed except the quietness of a fine Sunday morning’.[19] The aforementioned units were later joined by I.R.A. Chief of Staff, Richard Mulcahy, and from there they proceeded to the summit of Kilmashogue.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to the I.R.A, a party of Auxiliaries and R.I.C. under the command of Major George Vernon Dudley lay in wait at the nearby St. Columba’s College for the arrival of the I.R.A.[20]

Dudley, a decorated veteran of the First World War, was a colourful character whose chequered career in Ireland embodied the maligned stereotype of the Auxiliaries and Black and Tans as a group of drunken, thieving louts.[21]

Dudley was in command of a company of Black Tans who were involved in the infamous Croke Park Massacre on 21 November 1920.[22] He deserted the R.I.C. in January 1922 following an investigation by the British Treasury which had discovered that the accounts of E Company Auxiliary Division, of whom Dudley was commander until November 1920, showed a deficiency of £61; the blame was placed firmly on the head of Dudley, and attempts were made to prosecute him for defalcations in his company’s accounts.[23]

Dudley reappears in a report by the Fermanagh Herald on 29 July 1922 in which it is stated that a bench warrant had been issued against him for the alleged embezzlement of £300 of constabulary funds.[24] He fled first to Glasgow, and then on to Fiji, before being appointed Commissioner of Police for the Australian Northern Territory in March 1924.[25] Dudley was relieved of his duties a mere two years later, over the course of which he acquired a reputation for excessive drinking, and racked up debts of £320 1s 6d.[26]

Raid at Kilmashogue

Dudley’s party had received information regarding I.R.A. activity in the vicinity of St. Columba’s College, and as such, proceeded to the site on the morning of Sunday 19 September 1920.[27]

At the inquest held by Dr. Leo Byrne, City Coroner, at George V Hospital on 22 September, Dudley stated that his A.D.R.I.C. company discovered ‘30 odd’ men drilling in an open field within the vicinity of St. Columba’s ground. He instructed ten of his men, under the command of Sergeant Duffy (A.D.R.I.C.), to initiate a flanking manoeuvre whilst he and the remaining twenty men proceeded to challenge the men who were drilling.[28]

Dudley claimed a shot was fired over the drilling party, after which they surrendered and were searched by Dudley and his men. During the searching operation Dudley claimed to have heard rifle fire which came from the direction of Duffy’s screening party, who upon returning to the main A.D.R.I.C. party, informed Dudley that they were fired upon by an armed five man group whom they then returned fire on.[29]

When called to give evidence Duffy alleged that he saw the five man I.R.A. party approaching his men from behind a hedge and issued two challenges to them, which went unheeded, before contradicting his previous statement by then stating that a revolver shot was fired by the I.R.A. party in reply to his warning, and that the group now numbered four.[30]

Duffy’s men then opened fire on the Volunteers ‘in return’, killing Seán Doyle. Three I.R.A. Volunteers were rounded up by Duffy’s men, and a fourth escaped; including the deceased Doyle, these numbers tally with Duffy’s initial assertion. Under further questioning, Duffy’s narrative began to unravel.

Mr Carrigan King’s Counsel, representing the military, asked Duffy if the men that his party challenged were facing them when Doyle was shot, Duffy replied in the affirmative. When he was asked if he was certain of that, he changed his answer to ‘some of them were’.

Carrigan followed up with a further question, asking Duffy ‘was the man who fell facing you?’ to which Duffy then replied ‘yes’.[31] Carrigan then drew Duffy’s attention to the testimony of Captain R.F. Bridges, R.A.M.C, George V Hospital who had inspected Doyle’s body and found a small entrance wound at the rear and an exit wound at the front on the left-side of the deceased’s chest; the bullet that killed Doyle had perforated his left kidney, stomach, and left lung, in addition to fracturing his second and third ribs.[32]

When his attention was drawn to the impossibility of Doyle having been in a position facing Duffy when he was shot, Duffy then claimed that Doyle had been turned ‘halfway round and put his hand in his pocket as if to draw something’. Duffy was then asked to explain the conflict between his evidence and that of the City Coroner, which he attempted to explain as thus, ‘the shot was fired from an angle, and it would naturally have got him in the side or back’.[33]

Conflicting evidence

There are several issues with Duffy’s less than convincing testimony, notwithstanding the conflict between his evidence and that of the City Coroner’s. Firstly he stated that the I.R.A. party, of whom Doyle was a member, numbered five men, Duffy then changed this number to four.

This was further contradicted when Duffy stated that the number of men arrested was three, that one of the I.R.A. party was shot dead (Doyle) and that another man escaped, bringing the number back up to that which Duffy initially gave. Numerical inconsistencies however, are the least problematic of the issues with Duffy’s testimony, which leads us to the question of the position in which Seán Doyle was situated when he was killed by Duffy and his men.

The Crown forces claimed that they had been fired on first.

The inquest into the death of Volunteer Seán Doyle was adjourned until the following Monday, 27 September, with the coroner expressing dissatisfaction with the conflicting testimony of Duffy and also in order to allow, at the request of Seán’s father Peadar, the admittance of evidence from the three men who were arrested in the company of his son at Kilmashogue.[34]

There were some heightened tensions on the evening of the inquest’s postponement, owing to the lateness of the adjournment the authorities neglected to inform the general public that the body would not be released until later that night. By 7.20 p.m. that evening a large crowd had gathered outside George V Hospital to receive the body of the deceased.[35]

‘Ugly scenes’

The mourners were disinclined to believe the word of the military guard and refused to leave the grounds of the hospital, with hundreds more congregating in the local area. An armoured military vehicle arrived on the scene and began to rile the crowd by traversing a horizontal line in front of the gathered crowds training its Lewis guns on the mourners.

The ugly scenes were brought to close when two priests intervened placing themselves between the military vehicle and the mourners. Peadar Doyle arrived sometime shortly after and confirmed the postponement of the inquest with those gathered outside the hospital, by 8.30 pm the crowds began to vacate the area.[36]

The evidence provided by one of the three witnesses, like that of the City Coroner, largely disagreed with the testimony of Sergeant Duffy.

Of the three men requested by Alderman Doyle, only one, Thomas P. Meade, was produced by the military authorities; the reason given by Captain Barrett of District Headquarters was that of the three men sought, two were still awaiting trial and as such were disbarred from attending the inquiry.[37]

Meade’s testimony

When Thomas Meade entered the witness box he stated, rather cautiously, that on the day in question he was in the company of a boy that he believed to be Seán Doyle, however he did not know Doyle personally.

When the men arrested at Kilmashogue on 19 September 1920 were brought to the Bridewell station they refused to offer up their names to the authorities, a tactic employed by the I.R.A. throughout the War of independence; Meade’s reluctance to admit to knowing Doyle was most likely a tactic devised to prevent a situation arising whereby he may have implicated himself or others in such a manner that he could possibly face further prosecution.[38]

More pointedly, Meade stated that the I.R.A. party was descending Kilmashogue hill when they encountered the screen party of Auxiliaries. He went on to state that almost immediately after the Auxiliaries raised their heads in view he heard shouts of ‘Hands up! Hands up!’ which was proceeded by gunfire; without warning or interval.[39]

Some of the I.R.A. party had dropped to the ground and lain down on the hillside upon discovering the Auxiliaries; others did so after the volley of shots was fired. Meade further stated that a second round of gunfire was issued by Duffy’s party as the I.R.A. lay prostrate on the hill, bullets whistled over his head, and the I.R.A. called out ‘we surrender’; after which he noticed a boy he believed to be Seán Doyle lying on his side with his head on his arm.[40] While he was prostrate on the ground, Meade heard of the arresting party bark an order: ‘If they move, fire and don’t miss, shoot them dead’.

The position of the I.R.A. party, on the ground at an elevated position, as described by Meade’s testimony is consistent with Doyle’s fatal wound as described by the City Coroner. Doyle was killed by a bullet with entered at an angle and travelled upwards from the lower back before exiting from the left-side of the chest, therefore it is highly likely that he was shot by oblique fire issued by the Auxiliaries situated at the foot of the hill in a ditch.[41]

Duffy’s claim that a member of the I.R.A. party was turned ‘halfway round and put his hand in his pocket as if to draw something’ was also refuted by Meade who stated that no such movement was attempted by any of the party of which he was a member.

Meade was not in possession of any firearms, ammunition, or incendiary devices when he was arrested, he did however admit that Seán Doyle may have been in possession of a bomb prior to the appearance of the auxiliaries but he could not recall whether Doyle had it in his possession when he was shot.[42]

Whilst the Auxiliaries were arresting the remainder of Meade’s party he stated that he heard one of them say ‘shot through the heart’ upon discovering Doyle’s body, Major Dudley’s party arrived at the scene shortly thereafter. The I.R.A. prisoners were then marched to St. Columba’s College under Dudley’s orders, who told his men that ‘if they move, fire, and don’t miss. Shoot them dead’ before adding ‘if any of my men are fired on I will shoot this bunch’.[43]

Further arrests

The events at base camp did not go unnoticed by those at the summit of Kilmashogue, as Jack Plunkett recalled:

‘When we arrived at the top we made preparations for the demonstration and a few more men, possibly about six, arrived. As no more came we started our demonstration and exploded several small charges. One of them was gelignite, two were tonite and at least one was ammonite. We knocked off about eight or nine charges. Between two of these explosives we heard quite a fusillade of shots and later on several more which we found difficult to account for’.[44]

Upon hearing the shots a scout was sent to investigate the scene, after the first scout failed to reappear in sufficient time a second was dispatched to the foot of the hill.

The two scouts returned a short time later and reported back to the summit party that the two Volunteer companies had been in the process of marching up to the summit when a considerable number of Auxiliaries appeared from behind the wall of St. Columba’s college and proceeded to arrest the Volunteers.[45]

Upon hearing of the roundup, the summit party split up, Mulcahy and O’Connor left the scene whilst a party comprised of Jack Plunkett, Liam Archer, Liam Doherty and James Tully went to investigate the scene at the base of Kilmashogue. When they returned to the site of the camp, they found the place in disorder and none of the men who were due to arrive were present.[46] Plunkett discovered the body of Seán Doyle and after examining the body, pronounced the boy dead.

Owing to his unfamiliarity with the deceased individual, Plunkett requested that Liam Archer should make an attempt to identify the corpse; which caused some disconcertion to the latter. Plunkett vividly described the scene stating, ‘I asked Liam Archer to have a look at him and was quite disgusted that he wouldn’t. The man’s shirt was completely soaked in blood. He was a son of Peadar Doyle, as I found out later’.[47]

Following the investigation of the base camp Plunkett and the remaining Volunteers dispersed cross country to Rathfarnham, while Doherty and Archer returned to Dalkey where they were staying.[48]

Addressing the jury at the resumed inquest on 27 September, Mr. O’Byrne (representing the family of the deceased), asked that they find that Seán Doyle was shot by members of the armed forces of the Crown without justification or without giving him any opportunity of surrendering; asking further that they hold that Doyle’s death was murder.[49] During his passionate plea O’Byrne drew the jury’s attention to the conflict of testimony between that of the military, and the evidence given by Thomas Meade and the City Coroner; whilst also citing negligence on the part of Major Dudley.

Mr Carrigan K.C. in his closing address for the Crown argued that the Crown forces were within their rights to shoot down any members of the ‘non-regular’ army who they found marching under arms.[50] Despite the best efforts of Mr O’Byrne the jury found that ‘the deceased, John [sic] Doyle died on the 19th inst. From shock and haemorrhage following gunshot [sic] wound fired by the armed forces of the Crown’.

Seán Doyle’s funeral

The funeral of Seán Doyle on 23 September 1920 was marked by an impressive display of Irish nationalist solidarity. A number of local authorities passed resolutions of sympathy with the family of the deceased and several local businesses closed their premises on the day of the funeral as a mark of respect.[51]

The coffin was draped in the tricolour and carried aloft by comrades of the deceased from James’ Street RC church to the hearse which then proceeded to the Oblates Church in Doyle’s native parish of Inchicore.[52]

Throngs of mourners lined the route of the cortege’s procession, which according to the Irish Independent, took twenty-five minutes to pass any given point.

A cycle corps of Volunteers headed the procession, which also included members of Cumann na mBan, Na Fianna Éireann, and representatives of the ITGWU, in addition to the chief mourners-the deceased’s family. Arthur Griffith, William and Philip Cosgrave, and Joseph McGrath were among a number of representatives of Dáil Éireann also in attendance.

Throngs of mourners lined the route of the cortege’s procession, which according to the Irish Independent, took twenty-five minutes to pass any given point. The cortege travelled from Inchicore eastwards towards Kilmainham before turning westward on the Inchicore Road and proceeding through Ballyfermot towards Lucan where Doyle’s body was finally laid to rest in Esker cemetery.[53]

‘It was a lesson never to discount local knowledge’

The decision by the I.R.A. to proceed as planned with an explosives demonstration, despite prior warning by local intelligence that British Crown forces were in the vicinity of the camp, was foolhardy and recklessly negligent.

By September 1920, raids and ambushes of known I.R.A. haunts by British Crown forces had begun to bear fruit.[54] By refusing to heed the received intelligence the I.R.A. effectively walked right into an A.D.R.I.C. ambush, as Liam Archer later stated, the event at Kilmashogue ‘…was a lesson never to discount local knowledge’.[55]

Plunkett was emphatic on the point that Rory O’Connor was made aware of the possible presence of a military force at Kilmashogue yet he declined to alter the plans for the demonstration; information was passed on to Plunkett on Saturday 18 September 1920, and again on the morning of the demonstration, 19 September 1920.[56]

Liam Archer placed the blame on the recalcitrant Mick McEvoy, who he stated chose to ‘deride’ the warning from the Rathfarnham Volunteers that the military had occupied St. Columba’s College.[57]

Inquest verdict

The final sitting of the inquest into the death of Seán Doyle made no mention of any revolvers, or other firearms found in the possession of the arrested men at the scene, as Duffy and the official account from Dublin Castle initially claimed.[58] Despite his request, Mr. O’Byrne was denied the opportunity to cross-examine Major Dudley and Sergeant Duffy.[59]

It appears that Seán Doyle was shot dead by a member of Sergeant Duffy’s A.D.R.I.C. screen party whilst unarmed and in the process of surrendering

Conversely, O’Byrne’s defence was somewhat hampered by the refusal of the military to release the two other men arrested at the death of Seán Doyle to testify in their defence; although their refusal to give their names to the police had little positive effect upon their plight.

It appears, when all of the available evidence is considered, that Seán Doyle was shot dead by a member of Sergeant Duffy’s A.D.R.I.C. screen party whilst unarmed and in the process of surrendering, as suggested by his comrades and the nature of the fatal wound which he received, as attested to by the City Coroner.[60] The jury found that Mr. Seán Doyle’s death was due to haemorrhage following a gunshot fired by the armed forces of the Crown.

His death during the ambush at Kilmashogue was the first fatality executed by the recently arrived Auxiliaries in County Dublin, although despite the impressive scenes at Doyle’s funeral, his death has largely been sidelined from the historiography of the period, occurring as it did in the midst of a period of escalating violence and high-profile events such as the Rineen Ambush, the deaths of Kevin Barry and Terence MacSwiney and other such contemporary occurrences.[61]

His eulogy was penned by fellow comrade Seán Ó Conchubhair, who wrote ‘he fell, in the fight for Native Land, on an Irish mountain side, in the sacred cause of Liberty the youthful hero died’.[62]

References

[1] Freemans Journal, 22, 23 and 28 Sept. 1920; Irish Independent, 21, 23, 24, 27 and 28 Sept. 1920; Irish Times, 28 Sept. and 2 Oct. 1920; Cork Examiner, 23 Oct. 1920; Nottingham Evening Post, 22 Sept. 1920; Leitrim Observer, 25 Sept. 1920.

[2] II, 23 Sept. 1920; IT, 28 Sept. 1920; Strabane Chronicle, 25 Sept. 1920.

[3] SC, 25 Sept. 1920.

[4] II, 23 Sept. 1920; Lieutenant William James Duffy b. Lancashire 17 Feb. 1894, enlisted 31 Aug. 1920, awarded Military Cross, former member of the Black Watch, issued with service no. 462, re-engaged 12 Aug. 1921, placed on reserve 16 Jan. 1922. W. J. Duffy, Auxiliary Division – Register no. 1 – Numbers 1-1516 (National Archives United Kingdom [TNA UK], Royal Irish Constabulary [R.I.C.] Service Records 1816-1922, HO 184/50); W. J. Duffy, Auxiliary Division – Journal no. 1 (TNA UK, R.I.C. Records 1816-1922, HO 184/52)

[5] Robert Holland, witness statement (Irish Military Archives [IMA], Bureau of Military History [BMH WS] 280 (2)); Billy Rowe, interview (University College Dublin Archives [UCDA], Ernie O’Malley [EOM] notebooks, P17b/110 (137))

[6] Robert Holland, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 280, p. 48)

[7] Weekly Irish Times, The Sinn Féin Rebellion handbook: Easter 1916 (Dublin, 1917), p. 64; In his personal reminisce of the revolutionary period, Peadar Doyle recalled that following his identification as ‘a person of importance’, Major John MacBride attempted to intervene on Doyle’s behalf, stating that Doyle’s selection as a member of Volunteer G.H.Q. had been a mistake. However, MacBride’s attempt at reprieving Doyle was to no avail, see Peadar S. Doyle, ‘Reminiscences of five years service of an Irish Volunteer’ (IMA, BMH Contemporary Documents [CD] 97 (18)); MacBride and Doyle did have some grounds for concern as Doyle was later accused during his court martial of having taken part in revolt at Jacob’s factory, when he had in fact been stationed at the S.D.U.

[8] Peadar Doyle, Military Service Pensions Application [MSPA] (IMA, Military Service Pensions Collection [MSPC], W/34/REF/2335); List of Irish prisoners in English convict prisons (Portland), 6 May 1916 (TNA UK, HO 144/1453/311980/21); Register of Irish prisoners, 24 Apr. 1917 (TNA UK, HO 144/1453/311980/97)

[9] Peadar Doyle, MSPA (IMA, MSPC, W/34/REF/2335); Doyle was elected as a member of Dublin City Corporation in 1918, a post which by his own admission, took up most of his time during this period; Both Pádraig Ó Conchubhair, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 813) and Robert Holland, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 280), detail the involvement of local youths during the War of Independence, many of which made the progression from Na Fianna Éireann to the I.R.A.; see also ‘The Fourth Battalion’ in National Association of the Old I.R.A., Iris Drong Átha Cliath: The Dublin Brigade Review (Dublin, 1939), pp 35-52.

[10] James Tully, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 628, pp 1-2)

[11] Jimmy Ryan papers (UCDA, EOM notebooks, P17b/92)

[12] ‘The Fifth Battalion (Engineers)’ in Iris Drong Átha Cliath, pp 54-57 (54); Liam O’Doherty, interview (UCDA, EOM notebooks, P17b/91)

[13] Liam O’Doherty, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 689, p. 3); The ‘Sapper Section’ which O’Doherty is referring to was a precursor to the I.R.A.’s Engineering department, and as such its members were trained in a variety of roles such as map reading, demolitions, and signalling, building and repairing roads and bridges, laying and clearing mines.

[14] Ibid, p. 4.

[15] Ibid, p. 5; Seán’s employment as an apprentice fitter at Dublin Corporation’s Stanley Street workshop would have provided him with many of the skills and tools sought of recruits to the Engineers.

[16] For a detailed account of I.R.A. munitions manufacturing see, Patrick McHugh, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 664); Ibid, interview (UCDA, EOM notebooks, P17b/110); Michael Lynch, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 511); Ernie O’Malley, Rising out: Seán Connolly of Longford (Dublin, 2007) chapters 5 & 7. ‘War flour’ was a gelignite substitute manufactured by the I.R.A.’s Chemical Unit.

[17] Liam Archer, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 819, p. 16); Jack Plunkett, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 865 (31))

[18] Liam Archer stated that Mick McEvoy (No. 3 Section O/C) ‘derided’ the warning and proceeded to the site as planned with his unit on 18 Sept. 1920, Liam Archer, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 819 (16)); Jack Plunkett recalled informing Rory O’Connor of the warning yet ‘the orders were left unchanged’, Jack Plunkett, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 865 (31))

[19] Jack Plunkett, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 865 (31-32))

[20] Major George Vernon Dudley b. 21 Oct. 1884 at Oxfordshire, awarded Distinguished Service Order, appointed 6 July 1920 on recommendation of Major Heming, resigned 19 July 1920 and subsequently reappointed as a Temporary Cadet (19 Nov. 1920) by instruction from the Inspector General. To Maherafelt, Derry 1 Jan. 1921, promoted 3rd class District Inspector whence he deserted 5 Jan.1921, subsequently dismissed 5 Jan. 1922. Major George Vernon Dudley, R.I.C. General Register – Nos. 71001-73000 (TNA UK, R.I.C. Service Records 1816-1922, HO 184/37); Major George Vernon Dudley, RIC General Register – Numbers 75001-77000 (TNA UK, R.I.C. Service Records 1816-1922, HO 184/39); Major George Vernon Dudley, Auxiliary Division – Register no. 1 (TNA UK, R.I.C. Service Records 1816-1922, HO 184/52);

[21] Many I.R.A. veterans in the years after the conflict recounted real and also unsubstantiated anecdotes concerning the general character of the Auxiliary and Black and Tan forces. ‘According to legend, the Black and Tans were ex-convicts and psychopaths, hardened by prison and crazed by war’. D.M. Leeson, The Black & Tans: British police and Auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence (Oxford, 2011), p. ix.

[22] D.M. Leeson, ‘Death in the afternoon; the Croke Park massacre, 21 November 1921’ Canadian Journal of History/Annales Canadiennes d’Histoire, 38 (April/Avril 2003), pp. 43-67, (50).

[23] Major George Vernon Dudley, R.I.C. Officers’ Register – Vol. 3 (TNA UK, R.I.C. Service Records 1816-1922, HO 184/47)

[24] Fermanagh Herald, 29 July 1922.

[25] Ernest McCall, The Auxiliaries: Tudor’s Toughs, A study of the Auxiliary Division Royal Irish Constabulary 1920-1922 (Boston, 2010), p. 269.

[26] W.R. Wilson, A Force Apart?: A History of the Northern Territory Police Force 1870 – 1926 (Unpublished PhD thesis, Northern Territory University, 2000), p. 111.

[27] NEP, 22 Sept. 1920.

[28] ‘Report of the court of inquiry into the death of Seán Doyle’, II, 23 Sept. 1920.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid; The chest wound was also witnessed by W. Kidd-Davis who discovered Doyle’s lifeless body. W. Kidd-Davis, ‘An eye-witness account of what happened at Kilmashogue, Rathfarnham, Co. Dublin, and the shooting of Alderman Doyle’s son’ (IMA, BMH WS 650)

[33] II, 23 Sept. 1920.

[34] NEP, 22 Sept. 1920.

[35] FJ, 22 Sept. 1920.

[36] Ibid.

[37] II, 28 Sept. 1920.

[38] Ulster Herald, 25 Sept. 1920; II, 27 Sept. 1920; Bill Gannon, interview (UCDA, EOM notebooks, P17b/110)

[39] II, 27 Sept. 1920.

[40] FJ, 28 Sept. 1920.

[41] ‘Report of the court of inquiry into the death of Seán Doyle’.

[42] II, 28 Sept. 1920.

[43] IT, 28 Sept. 1920.

[44] Jack Plunkett, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 865 (32))

[45] Liam Archer, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 819 (16)); Jack Plunkett, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 865 (32))

[46] James Tully, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 628 (2))

[47] Jack Plunkett, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 865, p. 33)

[48] Liam Archer, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 819, p. 16)

[49] IT, 28 Sept. 1920.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Seosamh Ó Broin, Inchicore, Kilmainham and District (Dublin, 2006), p. 192.

[52] FJ, 23 Sept. 1920.

[53] National Graves Association, The Last Post (Dublin, 1932), p. 73; II, 24 Sept. 1920.

[54] ‘Dublin District Historical Record’, Record of the Rebellion in Ireland, 1920-1921 and the part played by the Army in dealing with it, 4:3 (May. 1920-Dec. 1920) reproduced in William Sheehan (ed.), Fighting for Dublin: the British battle for Dublin, 1919-1921 (Cork, 2007), p. 24.

[55] Liam Archer, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 819 (12))

[56] Jack Plunkett, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 865 (31, 35)); ‘Rory O’Connor had got another warning besides mine, but the demonstration was deliberately proceeded with in the absence of definite and detailed information as to the proposed attack’, Plunkett, op. cit.

[57] Liam Archer, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 819 (16))

[58] CE, 21 Sept. 1920; Seán Doyle, newspaper cuttings, civilians tried by courts martial (TNA UK, WO 35/107/4)

[59] II, 28 Sept. 1920.

[60] Michael Cremin who received news of the ambush from a fleeing Volunteer from Kilmashogue whilst with his company ‘a few miles away in the Pine Forest’ also confirmed that the Auxiliaries encircled the I.R.A. party and that none of the latter was armed. Michael Cremin, witness statement (IMA, BMH WS 563 (12)

[61] The Kerryman, 25 Sept. 1920; Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence (Dublin, 2004), p. 84.

[62] Seán Ó Conchubhair, ‘On the Death of Seán Ó Dubhghaill’ in Idem, The Kincora book of verse (Dublin, 1926), pp 157-158.