The Rise and Fall of the Dáil Courts, 1919-1922

By John Dorney

The Republican or Dáil Courts were one of the signal achievements of the Irish nationalist revolution of 1919-21.

Across much of the country, the British system of justice was replaced entirely and largely peacefully, for a time, with Irish Republican courts, before they were suppressed by force.

In late 1921 after the truce that ended hostilities with the British, and the Treaty that established the Irish Free State, it appeared as if the Dáil Courts might be for the basis for an Irish judicial system, removed entirely from its British predecessors.

The Republican or Dáil Courts were one of the signal achievements of the Irish nationalist revolution, but were abolished acrimoniously in 1922.

But it was not to be. Many of those in authority in the new Free State disliked the Dáil Courts, seeing them as a dangerous revolutionary innovation. According to Minister for Home Affairs, Kevin O’Higgins, in 1923;

You had through the country an improvised system of justice which was forged more as a weapon against the British administration in exceptional times and exceptional circumstances than as a definite system which would meet and answer the needs of normal times. [1]

The Dáil Courts were abolished amid the acrimony of the Civil War over the Treaty in 1922 and actively suppressed by the Free State authorities as an expression of anti-Treaty Republican sentiment.

They were replaced largely with the resurrected legal system as it had existed before 1919. For this reason, the rise and fall of the Dáil Courts tells us much about what the Irish revolution did and did not accomplish; how clean was the break with the past and how innovative the new Irish structures really were.

National Arbitration Courts

The First Dáil was the parliament of the Irish Republic set up by Sinn Fein MPs, who were elected in the general election of December 1918, and unilaterally declared Irish independence from Britain.

The Dáil Courts, which eventually functioned as the Republic’s judiciary, at first sprung up from below rather than being imposed from above, in 1918-1919. Rising food prices, the suspension of land reform during the Great War and land hunger prompted an upsurge in ‘cattle driving’ and land occupations in 1917–18.

The The Dáil Courts began as a spontaneous local response to land agitation in 1918-1919.

With the Royal Irish Constabulary’s authority increasingly undermined by the Republican campaign against and boycott of the police, the years 1919–1920 saw an even greater wave of agrarian agitation in the west of Ireland. In many cases, Sinn Féin and Volunteer activists were involved, and indeed some of the Volunteers’ early actions in some areas were attacks on landlords, rent collectors or ‘land grabbers’.

However, while this economic conflict helped the nationalist revolution up to a point by undermining the existing law and order, it also threatened to destroy not only the remaining great landlords but also prosperous Irish nationalist farmers. Sinn Féin activist Kevin O’Shiel described the unrest as a ‘prairie fire over Connaught’, ‘sparing neither ranch nor medium farm’. The Volunteers as a result issued a directive forbidding their men from engaging in cattle drives or land grabs.[2]

One of the long standing tactics of agrarian activists in Ireland, going back to the days of the Land War in 1880s, was to set up their own courts, which dispensed, they considered, truer justice and fairer rents than those imposed by the state system. And so in the years 1918 to 1920, the tactic was revived. Many Sinn Fein branches in areas of the south and west set up arbitration courts to settle land disputes. These were voluntary bodies and their rulings did not initially claim to have the force of law. For this reason the British authorities at first tolerated them due to their calming of land agitation.

In 1920, however, as the conflict over Irish independence heated up, the Dáil Courts’ potential as a challenge to British rule, increasingly became apparent. In May 1920, the Republic formally adopted the Courts and they were put under the Dáil’s Department of Agriculture; an indication of their initial function as a means of resolving land disputes.

Kevin O’Shiel was put in charge of the Dáil Eireann Land Commission, an arbitration body set up mid-1920 to deal with land disputes which proved quite successful at clamping down on cattle driving and land occupations. In May 1920, instructions were sent to all Sinn Fein branches to establish arbitration courts.

From arbitration to Dáil Courts

However in June 1920, the insurgent Republican authorities upped the stakes further, transferring the authority over the Courts to their Ministry for Home Affairs under Austin Stack. The Dáil Courts were now to be seen as criminal and civil courts, declared to have the right to administer law in place of the British courts.

This, far more than the arbitration courts, was a direct challenge to the ‘King’s writ’ or the legitimacy of British rule in Ireland. The Dáil Courts were formally established by a decree of Dáil Eireann on June 29 1920 and directed to apply the law as it existed on January 21, 1919 – that is, the day the Dáil declared independence from Britain.[3]

There were to be three levels of Republican Court; in descending order, the Supreme Court, the district Court and parish court.

Kevin O’Higgins later described the courts’ structure; the lowest type of Court was a Parish Courts, ‘having jurisdiction in their respective parishes for the hearing of small civil claims under £10 in value and petty criminal offences’.

The Dáil Courts were formally established as rival civil and criminal courts to the British system in June 1920 at the initiative of Austin Stack.

Then there was the District Court or Constituency Court, which administered appeals from Parish Courts, civil claims from £10 to £100 in value, land title exceeding £100.

Then there was a special sitting of that District Court at which a Circuit Judge attended, presiding over criminal trials and civil claims not within the jurisdiction of the ordinary District Courts.

Finally, the Supreme Court had ‘unlimited jurisdiction over all civil and criminal cases, and also heard appeals from the Circuit Sittings of the District Courts’. [4]

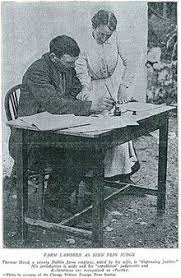

Parish judges were elected by local bodies including the Sinn Fein branch, the militant organisations the IRA and Cumann na mBan, the local trades council and farmers’ groups and local clergy. The profile of Republican judges was quite egalitarian; many were young men, some were trade unionists and some were even women, but also many were also Catholic priests.[5]

However, considerable effort also went into recruiting senior legal figures were to act as district and supreme Court judges and to draw up codes of procedure and rules for the Courts. A. Cleary, a professor law at University College Dublin, was made head of the Supreme Court while a number of prominent lawyers, notably Cahir Davitt and Diarmuid Crowley were appointed as district judges.

Davitt was the son of nationalist leader and land agitator Michael Davitt, while Crowley was long-time supporter of Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Fein and had written for various separatist newspapers including Griffith’s United Irishman. It was Davitt and Crowley, mainly, who wrote the rules and procedures for the Dáil Courts, and in the summer and autumn of 1920, travelled the country holding district and circuit courts.[6]

The Dáil Courts in action

The Dáil Courts were a curious mixture of the revolutionary and the conservative. The boycott and replacement of the British justice system was a bold strategy, but the law used was almost exclusively British Common Law and the right to private property was rigorously upheld. Efforts were also made to include the existing legal profession.

The Republican Chief Justice, Conor Maguire, remembered that ‘solicitors, even those with no sympathy for Sinn Féin, found it necessary if they were to retain their business, to practice in the Courts’.[7]

Dáil Courts were operating all over the country by the summer of 1920, in County Donegal for instance, courts sprung up at, Dungloe, Glenties, Bundoran and Killygordan. This went parallel to a campaign in which the IRA burned the existing court houses at Donegal town, Inishowen, Buncrana and elsewhere. [8]

In Dublin the Republicans set up at least two clandestine Dáil Courts, in Pembroke and Rathmines wards, staffed by four Justices each, on whom had to be woman and one a priest.

Until their suppression, the Dáil Courts had begin to replace the British legal system in Ireland.

According to Maire Comerford, a Cumann na mBan Republican activist, the Pembroke Ward Court was held in Aine Heron’s house in the salubrious suburb of Ballsbridge and there were some attempts at enforcing a vision of social justice. A money lender, for instance, who had charged interest of 800% was ordered not to be repaid. On that occasion though the Republican Minister for Home Affairs, Austin Stack (who operated out of an underground office on Henry Street) stepped in to reverse the decision.[9]

Industrial disputes were also dealt with by the Dáil Courts. Though some Republicans sympathised with organised labour, the priority of the movement was national unity, which sometimes created tensions between class and national aims. In September 1920, for instance, at a creamery strike in Cork city, workers refused arbitration and the IRA was called in to escort milk through the picket line. The problem was that many of the strikers were also IRA members. An open split was avoided when an agreement was patched up by the ITGWU and IRA, and arbitration of the Dáil Courts reluctantly accepted.[10]

By mid-1920, the regular British administered courts were finding they had no cases to deal with. Charles P. Crane, a magistrate in Kerry, found on entering his court in February 1920 no-one there except a young man smoking a cigarette, in an ‘insolent’ way. He ordered him to leave, only to find nobody to carry out his orders. ‘I could do no more than adjourn.’ A month later, after receiving a death threat for jailing Volunteers for military drilling, he quit and returned to England.[11]

In County Cavan, Sean Sheridan remembered, ‘The Volunteers had the co-operation of the vast majority of the people, something the RIC could never get… Some locals in Cavan who took Sinn Féin to the British courts over their occupation of a hall got a visit from members of the Bailieboro Volunteers which ‘compelled them to withdraw proceedings’.[12]

In the summer of 1920,whether because of the popularity of the Dáil Courts, or intimidation of jurors, assizes, or the local courts system, failed all over Ireland. In County Cork, only 12 of 296 jurors attended sessions and Cork Corporation, dominated by Sinn Féin, banned the British District Courts from using the city courthouse.[13]

Notwithstanding the relative success of the Dáil Courts, there remained the difficult problem of enforcing its verdicts, which, if arbitration was not accepted, had to be done by force. The Republic had no prisons, so more creative methods of punishment had to found.

In Cork, Volunteers caught a gang who had stolen £15,000 in Millstreet, deported the thieves from the country and returned the money.[14]

In County Galway, a land case was settled when tenants occupying farmland and demanding its redistribution were ordered to leave it because the land was too poor to be divided. When the claimants refused to accept the verdict, a Volunteer unit rowed them out to an island on Lough Corrib and left them there until they agreed to accept the ruling.[15]

In Cavan, petty criminals were arrested and made to work for farmers in another battalion area, while others were made to pay compensation to their victims.[16]

Those convicted of serious crimes in the Dáil Courts were sentenced to exile from Ireland, as there was nowhere secure to hold them.

Repression

The British had initially tolerated the Dáil Courts. In 1919 and early 1920, the British military even wrote approvingly of their success at keeping order in rural areas where RIC and regular courts no longer functioned.[17] That was as long as they were only voluntary arbitration courts.

However, as the Dáil Courts began to claim the right to impose their own law, by July 1920, both the RIC and British Army were soon pressing for the suppression of Dáil Courts, claiming they were undermining the ‘King’s writ’.

A government crackdown began in the autumn of 1920. Many activists were arrested. For instance, in Donegal Liam Duffy, of Donegal town, was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment for acting as registrar for the Sinn Fein Court in Donegal on Oct 20, 1920, in which 48 summons were found by the RIC when they raided the court. [18]

‘The Sinn Féin Courts have disappeared into the cellars’: David Lloyd George.

Among those imprisoned in the crackdown on the Courts was Diarmuid Crowley, one of the Republican Courts’ senior judges, who was arrested after holding an open Dáil Court sitting in Ballina, County Mayo, in defiance of a decree prohibiting it. He was sentenced to two years hard labour. Terence MacSwiney the Lord Mayor of Cork, was arrested for holding a Court there in August 1920 and later died on hunger strike. Also arrested was Patrick Hogan, the future Irish Free State Minister for Agriculture, who was arrested for holding a land court near Loughrea, County Galway and imprisoned in the internment camp at Ballykinlar, County Down.[19]

In County Kerry a man waiting to attend a Dáil Court was shot and killed by Crown forces.[20]

By such action, the Dáil Courts were driven underground and reduced to hearing cases in farms, barns, creameries and the like. The Courts and the Land Commission recorded a two-thirds fall in activity by early 1921. Prime Minister Lloyd George told parliament that the ‘Sinn Féin Courts have disappeared into the cellars’.[21]

After the Truce

Judges such as Cahir Davitt did their best to keep the Republican Courts alive during the War of Independence, but it was only once hostilities had ceased that they began to re-emerge into plain sight.

Following the Truce of July 11, 1921, the Minister Austin Stack made a concerted attempt to get the Dáil Courts back up and running. It was in this period when they emerged from the shadows to which they had been driven during hostilities, that the Dáil Courts, began to really take the place of the old justice system.

Diarmuid Crowley, who was released from imprisonment after the Truce, became the Supreme Justice of the Dáil Courts.

After the Truce of July 1921, the Dail Courts were energetically re-established.

The truce period in fact saw two rival systems of police and courts operating, one belonging to the British administration and the other to the unrecognised Irish Republic.

There was an uncertain period of competition between the two systems during this six month interlude. In County Monaghan for instance, when the Irish Republican police arrested youths for drunkenness at the Carrickmacross fair, the RIC in turn arrested the Republicans for false imprisonment and sent them to Dundalk Gaol. Another three Volunteers were arrested for false imprisonment and holding an ‘illegal court’ at Castleblayney. And another Dáil Court was broken up by the RIC at Lisnaskea.[22]

At Stranorlar, in Donegal, the RIC raided a Dáil Court but no arrests were made as the participants claimed it was acting only as an arbitration court.[23]

Following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921 and the creation of the Irish Free State, the RIC was disbanded but it was as yet not at all clear yet what would happen to the Free State’s legal system.

Shortly after Treaty was approved in the Dáil, a decree was issued that the existing courts system should ‘continue to carry out their functions unless otherwise ordered’. But at the same time the Dáil Courts had already taken over many of their functions. [24]

There was thus for many months a strange situation in which two rival courts systems were operating under the new Irish Provisional Government. In the words of Kevin O’Higgins, who disliked the Dáil Courts;

Deputies will remember the period of dual jurisdiction—or dual lack of jurisdiction, to be more accurate—and all the abuses that grew out of that period. People going into one Court and finding the weight of evidence against them moved into the rival Court for an injunction to stay the other party to the litigation from proceeding further with his case in the Court which seemed likely to decide against them.[25]

O’Higgins also alleged that the Dáil Courts took it upon themselves to issue licenses for the sale of intoxicating liquor which they had no legal right to do.

The Government’s preference was that the old, pre-1919, courts system be revived, but the Dáil Courts were still operating, in fact they were largely the only courts operating in rural areas, and had ‘taken on a tremendous amount of new business’ during the truce period. [26]

The Donegal Democrat for instance, reported that a Republican Court was still operating in County Donegal on February 3, 1922 with three judges, Ambrose Kennedy, Bernard McGinty and Peter Slevin, and was still reported to be operating in May 1922.[27]

This curious duplication of legal systems mirrored the upheaval in the political system at the time. Following the approval of the Treaty there were, notionally at least, two separate governments in the nascent Free State, the Provisional Government, headed by Michael Collins and the Second Dail, still held to be the parliament of the Irish Republic, headed by Arthur Griffith.

Additionally following the split over the Treaty, there were, in effect two rival IRAs, pro and anti-Treaty, and whichever faction was dominant locally was charged with maintaining order in that area.

Civil War and the abolition of the abolition of the Dáil Courts

This ambiguous period of ‘dual power’ was abruptly brought to an end with the outbreak of Civil War between pro an anti-Treaty factions in Dublin on June 28, 1922, with the National Army attack on the anti-Treaty IRA base at the Four Courts.

After this point, the pro-Treaty Provisional Government began to enforce its claim to sole legitimate authority across the Free State.

The Dáil Courts, seen as a vestige of the Irish Republic that had been dissolved by the Treaty, were a direct casualty of the internecine struggle and were abolished by the Free State’s Provisional Government on July 25, 1922, in favour of reinstating the old pre-1919 legal system.

The Dáil Courts became a casualty of the Civil War; the Provisional Government abolished them after anti-Treaty prisoners appealed to them for release.

Kevin O’Higgins the Free State’s minister for Home Affairs, would later portray this as a mere rationalisation of the chaotic situation of early 1922 in which two rival courts systems existed.

That anomaly could only be ended in the way in which it was ended, by a frank recognition of the fact that all the official Courts and all the official machinery of justice in the country had passed definitely into the hands of a representative Executive responsible to the Irish people, through their elected representatives in the Dáil, and the hastily improvised Courts that had been set up through the country to tide over an exceptional period were abolished, and the official State Courts were adopted. [28]

In truth however, the abolition of the Dáil Courts was a far more fraught affair than the mere administrative rationalisation that O’Higgins depicted. First the Dáil Courts were suspended on July 11, 1922 about two weeks after the outbreak of the Civil War.

Diarmuid Crowley, who, since his release from imprisonment in late 1920 had been appointed as a Supreme Court judge for the Dáil Courts, heard an appeal from Count Joseph Plunkett, for the release of his son George, one of the anti-Treaty IRA members taken prisoner in the fighting at the Four Courts in Dublin. Plunkett petitioned Crowley for a writ of Habeas Corpus – that is, the right not to be arrested without charge.

Since none of the prisoners had been charged with a crime and since no special legislation yet existed to hold prisoners without trial, Crowley issued a decree ordering the Minister for Defence, Richard Mucahy, and the Governor of Mountjoy Prison, Colm O Murchada, to show cause of arrest or to release Plunkett by July 26.

It was the day before this deadline was up, on July 25 that the Provisional Government formally abolished the Dáil Courts.

Crowley refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of this decision and, declaring the abolition of the Dáil Courts to be illegal, ordered the arrest of Minister for Defence and Army commander Richard Mulcahy and of Mountjoy Governor O Muchadha. He also issued a decree ordering the Third Dáil, elected in June 1922, to convene, the parliament having been prorogued by Michal Collins after the outbreak of Civil War. [29]

Diarmuid Crowley the Dáil Courts’ Supreme Justice, was arrested and imprisoned for issuing a decree calling for the arrest of Defence Minister Richard Mulcahy.

Crowley may have had the theoretical authority of the Dáil Courts behind him, but the Government had the very real power of their armed forces and it was Crowley, not Mulcahy, who soon found himself under arrest for his dramatic gestures.

Crowley was picked up on O’Connell Street in Dublin at gunpoint as he was walking with his friend ‘Mr Holland, a pronounced Free Stater’. The Intelligence officers, he complained, ‘made threatening remarks and asked offensive questions’. Despite the intervention on his behalf of his friend, Cahir Davitt, the Judge Advocate General of the National Army, who ‘couldn’t fathom why Crowley was arrested’, he was held a prisoner in Wellington Barracks from his arrest on August 31st until early September.[30]

Crowley wrote to his friend and former colleague, Cahir Davitt, the new Attorney General of the Irish Free State:

From what I have since seen and heard I believe he is one of the body called ‘Intelligence Officers’ – a body specially created by Mr.[Richard] Mulcahy since he-became Minister for Defence, and apparently trained after the methods practised by the British Auxiliaries In this country, but with a great deal more coarseness and savagery than the Auxiliaries were capable of …

I have since been locked up in a filthy cell and have never undressed at night – Thursday to Monday – the two so-called blankets supplied being unclean. … The food given to the prisoners in these cells consists of the leavings of the common soldiers in the guardroom adjoining, who never use a knife or fork themselves.[31]

Diarmuid Crowley also told Davitt at around the same time telling of the beating of prisoners at Wellington:

Some of the occupants of this cell and the adjoining one have been frequently interrogated concerning themselves and other people and savagely assaulted. This is done by the ‘Intelligence Officers’ referred to. I have witnessed instances of it. Once when I was being interrogated myself another officer intervened and said: “This is a special case”.. This military savagery must be put down at any cost and law restored.[32]

Cahir Davitt visited Richard Mulcahy and secured Crowley’s release after ten days detention.

Minister George Gavan Duffy resigned from the Government over arrest of Diarmuid Crowley and the suppression of the Dáil Courts and of habeas corpus.

Gavan Duffy protested in parliament about the abolition of the Dáil Courts and their deprecation by the Provisional Government. He told the parliament that those involved in the Dáil Courts had nothing to be ashamed of. He protested at the derogatory remarks of the Minister had made about the men who ran the courts, ‘at great difficulty, for the Government of the day, and at great risk to themselves and their business’. ‘It was extraordinary the ability and skill with which these men, unversed in legal matters, throughout the country managed these tribunals, and was a great tribute to the common-sense of the people’.[33]

Gavan Duffy contended that a grave injustice had been done to the thousands who had unheard cases or appeals to the Dáil Courts at the time they were abolished. [34] The widespread use of the Dáil Courts, he contended, showed that they were not arbitrary or corrupt as some members of the government had claimed.

And to a degree he was vindicated by the course of events. Kevin O’Higgins, as the foremost historian of the Dáil Courts remarks, ‘fulminated about the stupidity and corruption of the Dáil Courts even while he was engaged in ensuring that their judgements would be perpetuated’. [35]

While the new Irish legal system, based heavily on its British predecessor, was set up in 1923, and 1924, it was found necessary to set up a commission, the Dáil Courts Winding Up Commission, under James Creed Meredith, once a Dáil Court judge and later a Supreme Justice in the Free State, to hear and settle the over 5,000 outstanding cases that had been before the Dáil Courts in 1923-24. [36]

Had the Dáil Courts been characterized by chaos and corruption as O’Higgins and his colleagues alleged, it seems odd that so many of their cases continued to be heard, largely by the same personnel, after their formal abolition.

Epilogue: Diarmuid Crowley

Diarmuid Crowley, following his release from detention, took not further part in the Civil War, but remained, to the end of his days, an unrepentant Republican and opponent of the Free State.

He turned down an offered post in the Dáil Courts Winding up Commission but demanded a pension for life as a Supreme Justice of the Dáil Courts.

The Free State authorities declined, but perhaps wishing to bury some of the acrimony of the Civil War and of the abolition of the Dáil Courts, did agree to pay him a pension of £750 a year – a very substantial sum at the time. Crowley continued demanding his full salary until 1934 when the High Court ruled that his claim was invalidated by his accepting of a pension.[37]

He never reconciled with the Free State, remaining a supporter of Sinn Fein and criticising Eamon de Valera and his Fianna Fail party for taking he Oath of Allegiance and entering the Dáil in 1927. The same year, Kevin O’Higgins, who had presided over the abolition of the Dáil Courts, was assassinated.

Crowley continued issuing inflammatory statements, in 1934, stating that Michael Collins had British Field Marshal Henry Wilson assassinated in June 1922, an action that precipitated the Civil War. He died, never having married, leaving over £7,000 and a substantial house on Dublin’s North Circular Road, in 1947.[38]

His story perhaps exemplifies the sad and contradictory end of the Dáil Courts.

In the end, the Dáil Courts, once a symbol of the grassroots enthusiasm and innovation of he Irish revolution, became a symbol instead of Civil War division and acrimony.

Listen to John Dorney and Cathal Brennan discuss the Dail Courts below.

References

[1] Kevin O’Higgins, Dáil debate 24 July 1923 https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1923-07-24/12/

[2] Fitzpatrick, David, Politics and Irish Life, 1913-1921: Provincial Experiences of War and Revolution, p.132

[3] Liam O Dubhir, in The Donegal Awakening. P. 134-35

[4] Kevin O’Higgins, Dáildebate 24 July 1923 https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1923-07-24/12/

[5] Borgonovo, John, ‘Republican Courts, Ordinary Crime and the Irish Revolution 1919-21’ in Justice in Wartime and Revolutions, (eds.) Margo De Koster, Herve Leuwers, Dirk Luyten, Xavier Rousseax, p.54

[6] Mary Katsonouris, Revolutionary Justice, History Ireland, 1994, Vol 2 and Padraic Dempsey, entry for Diarmuid Crowley, Dictionary of Irish Biography, p.1049-1051, Cambridge, 2009.

[7] Ryan, Comrades, p.139

[8] O Dubhir, Donegal Awakening, p.145-148.

[9] UCD Maire Comerford Papers LA/18

[10] Borgonovo, ‘Republican Courts, Ordinary Crime and Irish Revolution’ in Justice in Wartime and Revolutions., p56

[11] Dwyer, Tans, Terror and Troubles, pp.176-177

[12] Francis Connell, BMH WS 1663

[13] Borgonovo, ‘Republican Courts, Ordinary Crime and Irish Revolution’ in Justice in Wartime and Revolutions, p.59

[14] Borgonovo, ‘Republican Courts, Ordinary Crime and Irish Revolution’ in Justice in Wartime and Revolutions, p.53

[15] Campbell, Land and Revolution, p.281

[16] Sean Sheridan, WS 1613; Francis Connell WS 1663 BMH

[17] Sheehan, William, Hearts and Mines: The British 5th Division in Ireland 1920-1922, p.107.

[18] Strabane Chronicle Jan 29, 1921

[19] Dempsey, Crowley Dictionary of Irish Biography, William Murphy, Patick Hogan entry Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2009, p747-749

[20] Mary Kastonouris, The Winding Up of the Dáil Courts, 1922-25, An Obvious Duty,p.13

[21] Borgonovo,‘Republican Courts, Ordinary Crime and Irish Revolution’ in Justice in Wartime and Revolutions, p.62

[22] Anglo Celt November 17 1921

[23] The Belfast Newsletter Dec 7 1921

[24] Katsonouris, The Winding Up of the Dáil Courts, 1922-25, An Obvious Duty, p.14

[25] Kevin O’Higgins, Dáil debate on Dáil Courts Winding Up Bill , July 1923 https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1923-07-24/12/

[26] Mary Katsonouris, Revolutionary Justice, History Ireland, 1994, Vol 2

[27] Donegal Democrat, February 3, 1922

[28] Kevin O’Higgins, Dáil debate on Dáil Courts Winding Up Bill , July 1923 https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1923-07-24/12/ See also https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/tv-radio-web/from-the-archives-july-25th-1923-1.2296172

[29] Dempsey, Crowley, Dictionary of Irish Biography

[30] Correspondence between Davitt and Crowley contained in Cahir Davitt WS BMH

[31] Correspondence between Davitt and Crowley contained in Cahir Davitt WS BMH

[32] Correspondence between Davitt and Crowley contained in Cahir Davitt WS BMH

[33] Kevin O’Higgins, Dáil debate on Dáil Courts Winding Up Bill , July 1923 https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1923-07-24/12/

[34] Irish Times July 25 1923

[35] Katsonouris, The Winding Up of the Dáil Courts, p. 187

[36] Mary Katsonouris, Revolutionary Justice, History Ireland, 1994, Vol 2

[37] Dempsey, Crowley, Dictionary of Irish Biography

[38] Ibid.