Book Review: The Irish Civil War, Law, Execution and Atrocity

By Sean Enright

By Sean Enright

Published by Merrion Press, 2019

Reviewer: John Dorney

Sean Enright is a retired barrister and judge and has brought his legal training and insight to a trilogy of books on state executions during the Irish Revolution of 1916-1923.

This was a period which saw the British state judicially execute, by shooting and hanging, 40 Irish Republicans – the subject for Enright’s first two books – from 1916 to 1921.

However, a far greater number, 83 by Enright’s count, died in front of the firing squads of the Irish Free State in the Civil War of 1922-1923. This is the gruesome but fascinating topic of his latest work. The traditional republican figure for Civil War executions was 77, but as Enright shows, this did not include four men executed for armed robbery and two who were shot summarily by firing squad in Cork and Kerry just before the legislation allowing executions was passed.

The British executed 40 republicans from 1916-1923, but 83 died in front of the firing squads of the Irish Free State in the Civil War of 1922-1923

This is, in many ways, an unsettling work, and this is intended as a complement to the author. Enright unflinchingly shows that the executions were a weapon of war and that legality took, at best, a back seat in the thinking of the pro-treaty authorities, to defeating the ‘irregulars’ and winning the civil war.

As many acknowledged at the time, the executions were probably effective in this regard, especially as another 400 men, among the 13,000 or so prisoners, were sentenced to death. This meant that by the end of the Civil War the anti-Treaty IRA knew that prolonging their campaign further would inevitably result in dozens or even hundreds more executions of their imprisoned fighters. There is little doubt that this helped to break resistance to the Free State by the spring of 1923 and to bring the Civil War to an end.

Nor, by any means, did the Free State have a monopoly on dark acts committed during the war over the Treaty. The anti-Treaty IRA burned hundreds of homes, assassinated unarmed officers and pro-Treaty politicians on a number of occasions, and shot civilians in house raids and as alleged informers. In addition their campaign of material destruction of railways, roads and other infrastructure very nearly bankrupted the young Irish state at its birth.

However, in dissecting the Free State’s executions from a legal point of view, Enright shows that a government that claimed to be fighting to preserve law and order in fact took great liberties with the rule of law in prosecuting the Civil War.

Enright shows that a government that claimed to be fighting to preserve law and order in fact took great liberties with the rule of law in prosecuting the Civil War.

The legal basis for the executions was simply a resolution passed in the Dail in September 1922, which authorised the Army to hold military trials, with the power to sentence suspects to imprisonment or death for attacking state forces or for unauthorised possession of weapons or explosives.

In early 1923, Enright’s book tells us, even military trials were, for the most part, dispensed with. Now death sentences could be handed down by ‘military committees’ consisting of National Army officers in the localities, where the ‘factual basis’ of the case was ‘not in doubt’. This judgement of whether the facts were in doubt was at the discretion of army lawyers. Moreover, possession of weapons could now be inferred if arms were found near where the suspect was arrested.

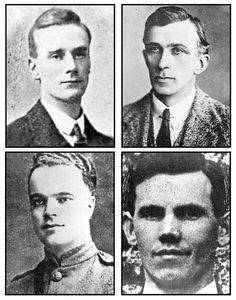

In December 1922, famously there was no legal process at all in the execution of four leading anti-Treatyites – Liam Mellows, Rory O’Connor, Dick Barret and Joe McKelvey, who were shot at Mountjoy prison in retaliation for the anti-Treaty IRA’s assassination of TD Sean Hales.

Prisoners initially had the right to legal representation, but this too, we learn here, went by the board in early 1923. And it is no coincidence that January 1923 saw the peak of executions with 34 anti-Treatyites being shot around the country in that month.

Enright suggests that National Army commanders such as Emmet Dalton, Tom Ennis and W.R.E. Murphy, who were reluctant to carry out executions, were all removed from their commands in late 1922 in order for the execution policy to be extended outside Dublin to all localities and therefore act as a greater deterrent. Indeed 1923 saw the firing squads in action from Kerry to Donegal and in such places as Athlone, Dundalk, Birr, Ennis, Tuam and elsewhere.

Not all of these locations were by any means, hotbeds of Civil War violence. And apart from the Mountjoy executions, few of those executed were senior republicans. Most were young men, of low rank in the ant-Treaty IRA. Some were not acknowledged IRA members at all but were shot for committing armed robbery. Others were National Army deserters.

All of which was retrospectively legalised by a new Public Safety Act enacted after the Civil War in mid 1923 and an Act of Indemnity for all acts committed by Free State forces during the conflict. As Enright notes, the Provisional Government in July of 1922 closed down the Dail Courts when anti-Treaty prisoners appealed to them for release under Habeas Corpus (the right not to be detained without trial) and arrested the Courts’ Supreme Justice Dermot Crowley.

This reviewer was taken aback to learn, however, that the Government also considered closing down the High Court of the Free State in November 1922, when Erskine Childers’ lawyers appealed to it. They argued that the military tribunals that had sentenced Childers to death had no authority over civilians. In the event, however, the Court ruled that suprema lex salus populi – ‘the supreme law is the safety of the public’, which amounted to saying that anything the government did to win the Civil War was legitimate.

In addition to the formal executions, Enright chronicles many of the ‘roadside executions’ or extra judicial killings, that the National Army carried out, including what amounted to a campaign of targeted assassination in Dublin and a series of reprisal massacres of anti-Treaty prisoners in Kerry in March 1923.

Enright perceptively remarks that the National Army evolved from a revolutionary guerrilla organisation – the IRA – and carried its mode of thinking: that threats must be eliminated and attacks to its own soldiers avenged, into the Civil War.

From this perspective, some of the civilian administration, notably Army Advocate General and future High Court Judge Cahir Davitt, do emerge from this book with some credit, as he and other judges did attempt to impose some legal limits on the Army’s actions and to end executions once the Civil War was over.

Judge Cahir Davitt, emerges from this book with some credit, as he and other judges did attempt to impose some legal limits on the Army’s actions and to end executions once the Civil War was over.

The descriptions of the firing squads themselves are affecting. Unlike the British Army, which carried out executions sequentially, the Free State’s forces would shoot prisoners in batches, meaning huge firing squads, many of whom did not aim properly. It was necessary in many cases for officers to deliver several more shots by revolver to the condemned prisoners’ bodies after the firing squad’s volley, to make sure that they were dead.

As Enright remarks a number of times throughout the text, detailed discussion of both the official and unofficial executions is hampered by the fact that all government records of them were destroyed by the outgoing Cumman na nGaedheal government in 1932 just before the Eamon de Valera’s anti-Treaty Fianna Fail party, victorious in the election of that year, assumed office for the first time.

This is a very good book, full of new information and legal insights. However, inevitably, as with all works, I do have a few minor criticisms. Some are mere oversights, for instance Free State premier W.T. Cosgrave is mistakenly introduced as Liam Cosgrave. This was in fact his son, who served as Taoiseach in the 1970s.

The description of the end of the IRA campaign is also a little unclear. It did not end, as implied here, with the death in action of Liam Lynch, on April 10, 1923, but with a ceasefire on April 30, followed by a dumps arms order on May 24.

Secondly the second half of the book seems somewhat rushed. There is a good discussion of the O’Higgins-Mulcahy rivalry in the Free State cabinet, and of Mulcahy’s removal of Liam Tobin and Charles Dalton as head of Army intelligence in late 1922. However these could profitably have been dealt with at slightly greater length. Dalton and Tobin’s intelligence department were most likely behind many of the extra-judicial killings, certainly in Dublin. They went on to attempt a mutiny in 1924.

O’Higgins’ feud with Mulcahy was, at least ostensibly, in part over the former’s indignation at illegalities carried out by the army. And Mulcahy’s proffered resignation as commander in chief of the Army in March 1923, was result of O’Higgins trying to gain oversight by the civilian ministers in the government over the Army.

This is a very good book, full of new research and keen legal sights, but its second half feels a little rushed.

A little more time could also have been devoted to the legacy of the Civil War executions. The narrative stops dead with the last executions at the end of 1923 and does not discuss, for instance, the ensuing wrangle over the handing over of the bodies of the executed to their relatives.

The executions also had a legal legacy, as the Free State continued to enact Public Safety Acts until 1931 and the de Valera government also used military tribunals to try to try civilians; first the Blueshirts and then the IRA, several of whose members were executed by the Fianna Fail government during the Second World War or ‘Emergency’.

This book would have benefited from a postscript on both the legal, political and emotional fallout from the firing squads of 1922-23. But perhaps there simply was not space.

However, this should not detract in any way from this book, which breaks new ground in chronicling and analysing the executions that, for better or for worse, helped to forge the new Irish Free State.