The life and death of IRA Volunteer Michael McInerney (1899-1921)

By Sam McGrath

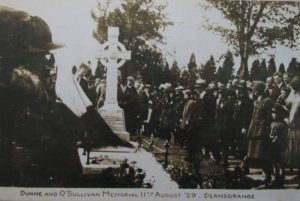

An impressive Celtic cross is the focal point of the Republican Plot in Deansgrange Cemetery, South Dublin.

Unveiled in August 1929, it commemorates three Irish Republican Army (IRA) members who died in London in the years 1921-22.

Reginald Dunn and Joseph O’Sullivan were hanged for the assassination of Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson outside his home in central London in June 1922. Both men – born and raised in London – had volunteered for British Army service during the First World War, with O’Sullivan losing a leg at Ypres, France.

Irish-born Londoner Michael McInerney is the third person named on the memorial cross. Also a former British soldier, the 21-year-old was fatally injured while manufacturing incendiary bombs for the IRA in July 1921.

McInerney was one of only three IRA volunteers killed on active service in England in the 1919-23 period.[1] The cities where the three died, London, Liverpool and Manchester, reflect major centres of Irish migration where the IRA had some of its best organised and most active units. After initially focusing on procuring and transporting arms to Ireland, the campaign of violence began in late 1920.

A couple of thousand of Volunteers were directly or indirectly involved in operations to destroy farms, warehouses, factories, railway signal boxes, timber yards and telegraph wire.

They caused hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of damage and raised awareness amongst the local English situation about the war in Ireland. A number of police officers, security guards and civilians were shot and wounded during these incidents. Attacks were also launched on the homes of ‘Black and Tans’ serving in Ireland and one suspected informer was killed by the IRA in London which will be discussed in detail later.

Background, from Clare to London

Michael McInerney was born on 28 August 1899 in a house in Pound Street, Kilrush, County Clare.[2] In 1901, the family was living at 1 Leadmore West, Kilrush.[3]

The McInerney family moved to Fulham, south-west London in 1902 or 1903.[4] The 1911 census shows that they rented three rooms on the top floor of 50 Townmead Road.[5]

Martin and his five children were joined by a boarder Charles Doyle (24), an unmarried general labourer from Athy, County Kildare. Bridget was a patient in the Fulham Infirmary (now Charing Cross Hospital) on the night of the census.[6] The exact reason for her hospital stay is unclear.

At the age of 17 and a half, Michael McInerney joined the Royal Irish Rifles regiment of the British Army.[7] This dates his enlistment to early 1916, in the middle of the First World War. His father said that his son was employed at a motor works on Bond Street before volunteering for service.[8]

Bridget died on 14 April 1916, aged just 37, in Kensington Infirmary of “tubercle of larynx” (tuberculosis of the voicebox). In August of that year, Martin attended a Military Service Tribunal to appeal for exemption from conscription. He gave “domestic reasons” and stated that “his wife was dead and he had five children, the [youngest] [9] … seven years-old and he had no relatives to care for them”. He was given “three months conditional exemption”.[10]

IRA Volunteer

Michael served 18 months in France during the First World War. [11] There is a medal card for a Private Michael McInerney of the Royal Irish Regiment (no. 7031) who was awarded the British War Medal and Victory Medal.[12] He was demobilised in early 1919.[13] The IRA’s guerilla war against British forces began in January of that year and a London Battalion was formed in October comprised of A Company (South West London), B Company (South East London), C Company (North London) and D Company (East London).[14]

Michael McInerney served in the British Army in the First World War, but when he returned home to London, joined the IRA

The initial focus of IRA units in Britain was the procurement, storing and transportation of arms to Ireland. From November 1920 onwards, they began active operations and launched arson attacks on farms, warehouses, factories, railway signal boxes and timber yards; destroyed telegraph and telephone wires and attacked the homes of ‘Black and Tans’ serving in Ireland.

A native of Fulham since childhood, Michael joined A Company (South West London) under the command of Seamus Moran. According to Moran, the unit began to collect information about local generators and power stations as potential targets. He named McInerney as his “informant in that area”.[15]

On 12 January 1921, a five man IRA team set out to kidnap former British officer John Bowen-Colthurst in Colchester, Essex.[16] A reviled figure throughout nationalist Ireland, he had been responsible for the death of an unarmed civilian and the execution of three prisoners including well known activist Francis Sheehy Skeffington during Easter Week, 1916.

McInerney drove from London with Seamus Moran and a Volunteer named Shortall while Reginald Dunn (Battalion Commandant) and Sean Golden (Battalion Quartermaster) took the train.[17] Moran recalls that it was pitch dark when they arrived. The IRA unit “manoeuvred around the house” but “before (they) got very far” a barking dog alerted a woman inside. This “made it useless … to go any further” and the operation was abandoned.[18]

One of the most significant operations undertaken by the London IRA during the period was closely linked to McInerney’s Fulham neighbourhood. On 3 April 1921, the body of 20 year old Vincent Fovargue was found on Ashford manor golf course in Middlesex. Fovargue had served as Battalion Intelligence Officer, 4 Battalion, Dublin Brigade for some weeks before being arrested by British forces.[19]

Under interrogation, he gave information about his IRA comrades which led to the arrests of Louis McDermott and other men of his former Company.[20] The authorities staged an ambush to allow his ‘escape’ and he subsequently moved to London where he attempted to integrate himself within the Republican movement, using the alias ‘Richard Staunton’.

Fovargue/Staunton attended several fundraising dances organised by the Fulham branch of the Irish Self-Determination League (ISDL) at the local Kelvedon Hall.

These events were frequented by members of the London Battalion’s A Company including, most likely, Michael McInerney. Frank Lee, a member of this Company, played piano at these dances and recalled that ‘Staunton’ made successive attempts to talk to him over the course of two or three weekends. “… As I had been warned about him, I did not have much to say to him”, Lee recalled.[21]

On the night of 2 April, Lee saw IRA Volunteers Martin Wallace, Brian O’Gorman, Reginald Dunn and Tom Monaghan at the hall’s exit door.[22] Martin Wallace wrote:

“At about 8.30pm … I was outside the hall. My instructions were to take no part if all went well, but if there were trouble, to make sure of Staunton and assist Comdt. Dunn and party to get away. Staunton was sent for – he came out of the Hall and after some conversation with Reg. Dunn and two others, the party got into the car and were driven away.”[23]

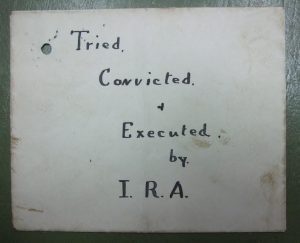

Vincent Fovargue was driven 14 miles to the golf course in Middlesex and shot dead. Four bullet casings were found next to his body the following morning and a note reading “Let spies and traitors beware – IRA.”

Foundation of a London unit of the GHQ’s Chemicals Department

A unit of the IRA’s General Headquarters (GHQ) Chemical Department was established in London in April 1921 to manufacture explosives for use against targets in England and Ireland. The team comprised of four men – Edward Cregan, Michael J. Kelly, Cecil Nolan and Michael McInerney – under the overall command of Dublin-based Seamus O’Donovan (Director of Chemicals).

IRA GHQ established an explosives department in London in April 1921. Michael McInerney was in it.

The men were each paid £4.10s.0d weekly by Sam Maguire and Sean Golden.[24] At least three of them (Kelly, McInerney and Nolan) were motor mechanics by trade.

Michael J. Kelly, a 1916 Rising veteran, moved to London in August 1920 to recuperate after his incarceration and hunger-strike in Mountjoy Prison. After several months, he resumed active service and joined the Chemical Department. Kelly was given control of a car used by the unit for operations and transporting material. He says that he:

“… took the car from Ml. McInerney (who) could drive but … had no mechanical training. As a result, it was not safe for him to go to a garage for repairs so I was asked to take it.”

Cecil Nolan, originally from Dublin, enrolled in the Irish Volunteers in London in 1918. He was appointed Company Intelligence Officer of London’s D Company in late 1919. He joined GHQ’s full-time staff in 1920 and was engaged in the purchase, storage and transport of arms. Nolan transferred to the Chemicals Department at its formation.[25]

Little is known about Edward Cregan as he does not appear to have applied for a Service (1917-21) Medal or a Military Service Pension. Nor is he mentioned in Witness Statements collected by the Bureau of Military History.

William Ahern, a GHQ Officer attached to the London Battalion, recalled that the unit started to manufacture incendiary bombs “as it was found almost impossible” to set fire to “large buildings by the ordinary methods”.[26] The team established workshops in “a garage and two private houses”.[27]

Greenwich factory

The small garage, at the rear of 9 South Street, Greenwich, south-east London, was rented out by landlord Robert Cook for 10 shillings a week to an IRA Volunteer posing as ‘James Edwards’ from Dulwich who said it was for a small motor car repair business.

Each week, Michael J. Kelly transported “aluminum powder, nitrate and scarings” from Senior Crozier & Co. Ltd. (chemical-supply business) to the Greenwich factory.[28] The company was owned by Francis Fitzgerald, a brother of Desmond Fitzgerald TD.[29] Negotiations with Fitzgerald were dealt with by Sam Maguire.[30] Kelly was also entrusted to deliver hundreds of the finished incendiary bombs to IRA safe houses in Bloomsbury and East Poplar.[31]

William Ahern has outlined that the devices were to be used for the “blowing up of Power Houses, Sewers, Underground Cable Junctions, Underground Railways, beneath the River Thames and the Thames Bridges”.[32] He had received “instructions to procure” six, old, one-ton lorries ”which were to be lined with steel and concrete, filled with explosives, detonated (and) fused”. When completed, they “could be driven anywhere required”.[33] Ahern claims that the Truce of July 1921 put a hold on this ambitious and possibly devastating bombing campaign.

Michael J. Kelly drove to the factory twice daily as “camouflage” for the supposed motor repair business.[34] Retired engineer William Leard, who lived above the garage, told the subsequent inquiry that the three young men were “very quiet (and) secretive and always busily engaged” in the workshop until 9pm each night.[35]

Explosion (July 1921)

The Truce – which came into effect on 11 July – did not seem to affect the factory’s production schedule. The IRA in Britain and Ireland continued to source arms, manufacture explosives and train its units in preparation for the resumption of hostilities if the talks broke down. In the last week of July, the factory was inspected by Sean Flood (Director of Operations, Britain). [36]

McInerney was killed in an accidental explosion at the IRA bomb factory in Greenwish on July 28, 1921.

It was in operation for just over three months when a premature explosion ripped the workshop apart. On 28 July 1921, Seamus O’Donovan (Director of Chemicals) traveled to London to meet the supplier Francis Fitzgerald and visit the Greenwich workshop. He was driven to these locations by Michael J. Kelly.[37]

McInerney, Nolan and Cregan were working on site as normal when a fire broke out about 12.45pm. This was caused by “the ignition of some incendiary mixture which was being prepared in a pan over a gas jet”, according to Nolan’s later testimony.[38]

William Leard had returned home for his lunch when, ten minutes later, he:

“… heard the first explosion. Smoke and fumes came up on the staircase, nearly choking and blinding me. I got my wife outside and then went back and I got my cash-box. At this time there was a second explosion and I was choking with the fumes. Before I could get out there came the big explosion and a tremendous volume of fumes came up the stairs, I just managed to struggle outside, but I was almost done.” [39]

Police Constable Thomas Bishop, on duty on Greenwich Road (about 50 yards away), first noticed “a large volume of smoke” before rushing to the scene.[40] Local resident, Mrs. Lillian Manderson, whose house (no. 11) overlooked the garage’s backyard, observed McInerney run out from the garage engulfed in flames and stumble against a wall.[41]

He “appeared to be in agony”.[42] She shouted to him “Isn’t there anyone who can help? You get to the hospital quick!”. She saw his two companions (Nolan and Cregan) run down the yard and called to them: “Can’t you get the ambulance to take that poor fellow to the hospital? He’s burning alive!’. Witnesses saw the men leave the scene in a Ford open touring car[43]

Cecil Nolan states that he took McInerney (“who was in a hopeless state”) to the Miller General Hospital, Greenwich, about half a mile away.[44] There his wounds were dressed but the young man refused to tell staff how he received the injuries.[45] Nolan left after half an hour due to the arrival of the police.[46]

When Martin McInerney reached the hospital and questioned his son about the cause of his burns, Michael told him that “I shall be alright tomorrow. I will let you know how it happened when I get up”.[47]

Dr. WG Hay of Guy’s Hospital, Southwark received a telephone call from the secretary of the Miller General who asked if he could take a patient “suffering badly from shock” as they had vacant beds.[48] McInerney was transferred to Guy’s Hospital at 3.30pm where he was visited briefly by Cecil Nolan.[49]

McInenrey had received burns to his back, arms, neck, face and ears, while his eyebrows and most of his hair were scorched off. [50] He died at about 3.30am on the morning of 29 July 1921 of “shock” and “syncope” (temporary loss of consciousness caused by a fall in blood pressure) due to his “extensive burns”.[51] Aged 21, his death certificate listed his occupation as a motor mechanic. It was reported in some newspapers that he was engaged to be married.[52]

McInerney was buried in St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green, north-west London, on 4 August 1921. There is no marker as the grave (number 11072) was reclaimed in later years.[53]

Cecil Nolan and Edward Cregan gave evidence at a London IRA enquiry into the explosion in front of Rory O’Connor (Officer Commanding Britain), Reginald Dunn (Battalion Commandant), Joseph O’Sullivan (Battalion Intelligence Officer), Sean Golden (Battalion Quartermaster) and T. McDermott (Unknown rank).[54]

An internal report from the IRA’s Director of Chemicals (dated 1 August 1921) outlined that their “incendiary shop in Greenwich” was wrecked in an accidental fire which had resulted in the “destruction of premises, some lathes and other machines, several hundredweight of finished incendiary stuff, and many hundreds of finished incendiary grenades.”[55]

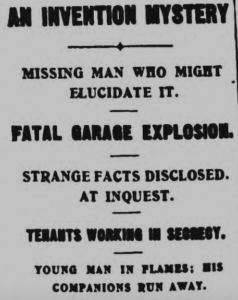

Inquest (Aug – Sep 1921)

The Southwark Inquest Court held three separate days of evidence, presided over by Deputy-Coroner Francis Danford-Thomas. Martin McInerney told the court on 1 August that he believed his son was working as a motor mechanic in Vauxhall, south central London.

His son did not smoke or drink and had been once or twice to dances but “never out all night”.[56] The inquest was adjourned for a fortnight.

Resuming on 15 August, Detective-Sergeant Richard Ball[57] and Divisional Detective-Inspector William Brown told the court that the police had discovered a cache of arms and incendiary munitions in the garage.[58] The bombs were described as “cylindrical in shape, very similar to a cocoa tin, made up of cardboard, tin, and strips of wire on the side”.[59]

The inquest jury concluded of Michael McInerney’s case: “death by misadventure, the result of burns received while engaged in the manufacture of incendiary bombs”.

The authorities also found Michael McInerney’s driving licence (issued 30 November 1920) and an internal IRA Chemicals Department document (dated 27 July 1921) which read:

“Re design clock apparatus. The general principle leaves very little room for criticism. The model appears to be to be as compact as it is possible to make it. I would suggest, however, that the powder box be secured in some way … where black powder is confined there is always the danger of explosion … if it is merely held with tacks there would be a tendency for it blow out possibly without lighting the cotton waste.”

Police also retrieved a letter addressed to McInerney from a Mr. M. Daly of 32 Vincent Square, Westminster referring (possibly in code) to a cricket match. Police subsequently searched Daly’s bedsit and found a revolver and some cartridges.[60]

Martin McInerney objected that the inquiry was to be adjourned for a second time and made his feelings clear about potential police indiscipline:

“… One of them visited the house on the day of the funeral and I believe he was the worse for drink and yesterday I was followed … to Mass. They won’t get anything by following me about.”[61]

The case concluded on 17 September 1921 with the jury returning a verdict of “death by misadventure, the result of burns received while engaged in the manufacture of incendiary bombs”. It was reported that Martin McInerney received “threatening letters” after his name and address appeared in the press.[62]

Chemicals Department members returns to Dublin

Michael J. Kelly fled to Dublin immediately after the explosion and was transferred to the IRA’s chemicals factory at 6 Peter Street under the command of Seamus O’Donovan and Joseph Dunne.[63] He remained with the unit until he was arrested by the Free State army in February 1923 in the last months of the civil war.[64]

Following the incident, Cecil Nolan said that he helped to establish new bomb-making factories in Wapping and later Beccles Street, Poplar. He returned to Dublin in January 1922 and was transferred to the Peter Street factory. He took the pro-Treaty side in the civil war and joined the Free State army in August 1922.[65]

Edward Cregan relocated to Dublin around the same time as Nolan, reported to GHQ but did not become attached to the Chemicals Department.[66] Nothing more is known about his activities or later life.[67]

Arrest of Martin McInerney (June 1922)

Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson was shot dead outside his London home on 22 June 1922 by London IRA members, Reginald Dunn and Joseph O’Sullivan. Police responded by raiding the houses of Irish Republican sympathisers across the city. On 26 June 1922, Eileen-Bridget McInerney opened the door to Detective-Sergeant McLeod[68] of Scotland Yard and other members of the (so-called) ‘Flying Squad’. The officers proceeded to search the rooms and found a number of suspicious items.[69]

Michael’s father Martin McInerney was arrested in June 1922 as part of a general round up of Irish suspects in London following the assassination of Field Marshal Henry Wilson.

Martin McInerney was taken into custody and charged at Canon Row police station, Westminster, with the unlawful possession of a collection of arms and other material.[70] Appearing before Magistrate Forbes Lankester in the West London Police Court, his defence lawyer, JH MacDonnell [71], described the small automatic pistol as a “souvenir pistol” which would “blow up if anyone tried to use it” and the rifles as an old type used in shooting galleries.[72]

MacDonnell admitted that the items belonged to his client’s son but underplayed any possible IRA connections:

“(Michael McInenrey) was in the Army, and had a good career there. He came home and was a bit of a mechanic, and fooled around with these dangerous implements. Last year he died as a result of injuries received by being seriously burned.” [73]

Martin McInerney apparently “knew nothing about the suggestion” that his son had been “making bombs for a Republican organisation”.[74] He told the court that the items found in his home were of sentimental value and he “would not give them for up for anybody.” [75]

The court believed the story and Magistrate Lankester was satisfied that there was “no evidence that McInerney intended to use these firearms for an improper purpose”. The property was confiscated and the Irish Self-Determination League (ISDL) paid McInerney’s £5 fine.[76]

Deportation of Martin McInerney (March 1923)

In the early hours of 11 March 1923, Martin McInerney was among 110 men and women with alleged Republican sympathies arrested by police across England, Scotland and Wales. With the cooperation of the Irish Free State government, they were transported from Liverpool to Mountjoy Prison, Dublin on the Navy cruiser HMS Castor.[77]

Martin and his family were deported to the Irish Free State but were eventually allowed to return to their home in London.

Both governments were afraid that the anti-Treaty IRA were planning to launch a new armed campaign in Britain. Many of the deportees were current or former IRA members but a great number were individuals like Martin McInerney with tenuous links to armed activity. Some of those arrested were British-born and were setting foot in Ireland for the first time.

Labour MP Herbert Dunnico raised the issue of Martin McInerney’s arrest in the House of Commons on 19 March 1923. He asked the Home Secretary, William Bridgeman, whether he was aware that by deporting McInerney, he had “rendered two motherless children Eileen (17) and Liam (14) without any protecting guardian or means of livelihood”.[78]

Dunnico also asked if the Home Secretary proposed “to make immediate provision for the care and maintenance of these children”. Bridgeman replied that he had learnt that “Martin McInerney … was in receipt of £2 a week from the Irish National Aid … Central Distress Fund.” This was the Home Secretary’s attempt to link Martin and his family to the IRA because they were receiving aid from an Irish Republican support group.

Martin was imprisoned in Cell 21, C Wing in Mountjoy Prison with another London deportee, Eamon Barry.[79] Thomas F. O’Sullivan, in the cell next door, described McInerney as a “nervous highly strung man” who “certainly suffered a great deal mentally when in prison”.[80]

Following their father’s arrest and deportation, Eileen and Liam moved to 36 Townmead Road where they stayed with a neighbour named Mrs. Miller or Mrs. Mills.[81]

The deportation orders were ruled illegal by the British courts and Martin McInerney was released on 17 May 1923. He sailed back to England on the SS Mayfield with 90 others. His fellow deportee, Thomas F. O’Sullivan, recalled meeting McInerney in July or August 1923 when he had “appeared to have recovered a good deal of his original strength”. However, McInerney was noticeably worried as his business had “been absolutely smashed up” because “his children were unable to carry it on while he was in Mountjoy”.[82]

Martin McInerney had been employed as a house decorator and sanitary engineer for 21 years by Messrs. Edwin Evans & Sons, auctioneers and estate agents, based at Lavender Hill, Clapham Junction.[83] He also acted as a part-time rent collector for the company. To supplement his income, Martin McInerney also delivered Irish eggs to customers in the Fulham area.[84] Having lost his job, he was forced to sell his horse and cart.[85]

Death of Martin McInerney (November 1923)

Martin McInerney became seriously ill around September 1923 and was admitted to the Fulham Infirmary where he died of “lobar pneumonia” on 13 November, aged 47.[86] His death was registered by his daughter Eileen and his occupation was listed as a “House Decorator (Master)”. He left £450 to Dr. Edward Leslie Burgin, the solicitor of his eldest living son John.[87] The Irish Independent reported that he was buried on 20 November 1923 in St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green presumably beside his son.[88]

On 17 January 1924, the Irish Deportees (Compensation Tribunal) heard claims from the legal representations of Martin McInerney and his family was awarded £650 in damages later that month. [89] What happened to Martin’s four siblings? See separate appendix at the bottom of the article.

Memory

Michael McInerney’s former comrades in the London IRA did their best to keep his memory alive until at least the late 1960s.

Michael McInerney’s former comrades in the London IRA did their best to keep his memory alive until at least the late 1960s.

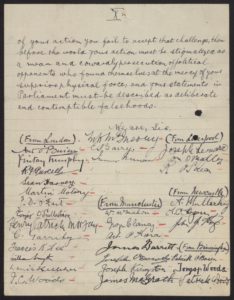

On 10 August 1922, a Mass was held in Holy Trinity Church, London for the memory of Reginald Dunn, Joseph O’Sullivan and Michael McInerney.[90]

Irish Republicans in London came together in 1929 to raise money for a memorial cross in Dublin for the three men. The committee consisted of Martin Wallace (President), Maire Ni Ceinneide (Mary Kennedy) (Secretary) and Sean Harrington.[91] An Phoblacht noted that Glasnevin Cemetery had refused a “a space for the erection of this monument”.[92]

On 11 August 1929, contingents from the IRA, its youth wing Na Fianna Éireann, Cumann na mBan, its youth wing Clan na nGaedheal and Sinn Féin assembled at Temple Hill, Blackrock and marched to Deansgrange Cemetery led by the Bray Pipers’ Band. The crowd of 500 was addressed by Frank Ryan and the main oration was given by Dublin Republican Sean McConnell who had just been released from prison. He declared that:

“… even in the capital of the British empire … there was, and is, a unit of the IRA … (which) has a proud record throughout every phase of the Irish fight for freedom 1916-23 … to that unit belonged Reginald Dunn and Joseph O’Sullivan and also Michael McEnerney (sic), whose name is also inscribed on this monument, who was accidentally killed while manufacturing munitions for Ireland’s soldiers” [93]

Mary Donnelly mentioned McInerney in her booklet The Last Post which was published in 1932 by the National Graves Association (NGA).[94] His first name was mistakenly recorded as James in the 1935 nominal rolls for the London Battalion[95] and as Simon by Ernie Noonan in a 1966 article in An tÓglach:

“…I must pay my humble tribute to the men of London who died for Ireland in later years. Simon McInerney, Reggie Dunne and Joe O’Sullivan and to those other unsung and forgotten men and women who gallantly upheld the proud tradition of the London Irish”.[96]

In the few mentions of McInerney in Irish newspapers, he was variously described as having been “killed when an ammunition dump exploded”[97]; “accidently killed during a training session”[98]; “died as a result of an explosion in a munition factory”[99] and “killed in saving the life of another (while) teaching a class in the making of bombs”.[100]

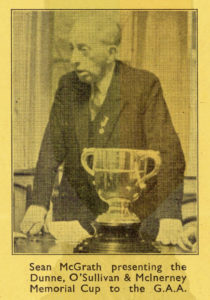

A new memorial committee was formed in London in August 1947 to commemorate the three men.[101] The joint treasurers were London IRA veterans Denis Brennan and Sean McGrath. Two silver cups, both named the ‘Dunne, O’Sullivan and McInerney Cup’, were presented to the Gaelic League of London and the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) London County Board.

From 1947 onwards, the Association of Old IRA and Cumann na mBan (London) organised a bi-annual ‘Foundation Mass’ to honour the memory of the three men.

The first Mass of the year was held in August at the Corpus Christi Catholic Church, Maiden Lane, Covent Garden, Westminster where the rector was Rev. Joseph O’Hear MD. A Glaswegian of Donegal stock, he had been a doctor before joining the priesthood.[102]

The second Mass was held in September at the Church of St. Michael and St. Mary, Commercial Road, East London. At each Mass, the congregation sang the hymn ‘Hail, Glorious St. Patrick’ which had been sung by around 100 people outside Wandsworth Prison in the early hours of 10 August 1922 as Dunn and O’Sullivan were being led to their executions.

The two Masses were held in August and September annually throughout the 1950s. In 1962, Frank Lee was forced to appeal for “greater support” as attendance was in decline. Admitting that this was a “sad thought for the veterans of those stirring days of the fight for Ireland’s independence”, he made his plea to the “Irish in London and all friends of Ireland”. [103] In 1967, a parade with a colour party and band marched to the Mass for the first time in forty years. [104]

In 1968, Lee complained to the Irish Independent that IRA veterans in the Corpus Christi Church had been prevented from singing the hymn ‘Hail Glorious St. Patrick’. He claimed that this was the first time in forty years that the tradition had been broken. The new rector Rev. Brian Nash told the press that he personally felt that the “hymn had no place in the Mass” as it introduced “a political connotation”.[105]

The last mention of the Mass specifically for Dunn, O’Sullivan and McInerney was in 1969.[106] In the early 1970s, there are references to a 1916 Mass in Corpus Christi in April which may have become the focal point for the dwindling number of IRA veterans in London.

Did the Mass end in the late 1960s? It’s likely. Firstly, Rev. Joseph O’Hear MD died in 1970. He had been rector of Corpus Christi from at least 1948 until the late 1960s. [107] His successor Rev. Brian Nash seems to have been less comfortable with the Mass. Secondly, the main organiser, Frank Lee, died in 1974. He was one of the last living IRA men in the city who had served with Dunne, O’Sullivan and McInerney and his passing would have ended the long continuity.

Thirdly, with the increasing violence in Northern Ireland at this time, it may have become more difficult or unsafe for Republicans in London to organise a Mass in memory of IRA men. Finally, a Foundation Mass seems to last 25 years [108] which means the committee paid for the Mass to be held bi-annually from 1947 until 1972.

However, an article in the Irish Post in 1998 mentions that Dunn, O’Sullivan and McInerney “are commemorated with an annual Mass at Corpus Christi Church” which took place on 9 August that year, so it would appear that the tradition continued or was revived.[109]

McInerney has been mentioned only a handful of times in published work in the last two decades. Journalist John Crossland referred to McInerney in a 1997 article in the Independent newspaper about IRA violence in London entitled ‘75 years of bombs and blunders’. [110] Historian Peter Hart recalled the premature explosion, but not McInerney by name, in his 2000 journal article on the IRA in Britain (1919-23).[111] Brian Noonan in his excellent 2014 study on the same subject gave two passing references to McInerney.[112]

As well as being the first comprehensive biography of IRA Volunteer Michael McInenrey, I hope this article also adds some new insight into our understanding of the IRA’s armed campaign in London between 1919-21.

The raids, arrest, imprisonment and early death of Michael’s father Martin personify the experience of the city’s Republican movement during the Civil War when it faced greater odds with a diminished membership and support base. The final chapter outlined the complex experience of how aging Irishmen and women in post-war London – a city still reeling from the Blitz and the IRA’s 1939-40 bombing campaign – endeavoured to preserve the memory of former comrades, including one who had been killed in the process of manufacturing incendiary devices.

If you have any further information or insight into any of the subjects covered, please email the author – matchgrams(at)gmail(dot)com

–

Note 1: I’ve used the spelling McInerney throughout for consistency. The family at different times spelt it Mcinerny or Macinerny. It has also been recorded in other sources as MacInnerney, Mcnearney, McInerry, McEnerny and McIverny. I also used the birth certificate spelling of Reginald Dunn although it is often spelt Reginald Dunne.

Note 2: Huge thanks to the following individuals – Jason Walsh-McLean and Andy McDonnell (for images); Gerard Costello and Mary Dudek (for information on the McInerney family); Stephen Coyle and Brian Smith (for archive material); Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc, Brian Hanley and Gerard Noonan (for help and suggestions) and Carolyn Fisher (for superb editing advice).

Note 3: Three of Michael McInerney’s siblings emigrated to the United States of America to start new lives. The fourth disappears from the records. For more information, read this separate appendix:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Z_rAKeqAappPrQ5fx519pu-EZm8rE_zUYCCNsmtFwhw/edit?usp=sharing

About the author:

Sam McGrath is a project archivist with the Military Service (1916-23) Pensions Collection (MSPC) and co-founder of the Dublin social history blog Come Here To Me!.

Endnotes:

[1] The others were Neill Kerr Jr. (24), a 1916 Rising veteran, who was accidentally shot in the head by his brother while handling arms in Liverpool on 3 September 1920 and Sean Morgan (21) who was shot dead by police during a raid on an Irish social club in Erskine Street, Manchester on 2 April 1921. In the period, Terence MacSwiney died on hunger-strike in Brixton prison on 25 October 1920 and Reginald Dunn and Joseph O’Sullivan were hanged in Wandsworth Prison on 10 August 1922.

[2] Michael McInerney birth certificate (28 August 1899), https://www.irishgenealogy.ie/

[3] 1901 Census Return, 1 Leadmore West, Kilrush, Co. Clare

http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1901/Clare/Kilrush_Urban/Leadmore_West_part_of_Urban/1082282/

[4] Martin McInenrey was employed for 21 years in London until his death in late 1923 so it possible to calculate that he moved to London sometime between the birth of his son Simon in July 1902 and the end of 1903

[5] 1911 Census Return, 50 Townmead Road, Fulham, London, https://www.findmypast.ie

[6] 1911 Census Return, Fulham Parish Infirmary, Fulham, London, https://www.findmypast.ie

[7] The West London Observer, 30 June 1922

[8] The Manchester Guardian, 02 August 1921

[9] The Fulham Chronicle, 04 August 1916. The newspaper article states ‘oldest’ by mistake when it should be ‘youngest’.

[10] ibid

[11] The Kentish Mercury, 5 August 1921

[12] Medal card of Michael McInerney (Royal Irish Rifles) WO 372/13/9032, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D3823780

[13] The Dundee Courier, 02 August 1921

[14] Letter from Sean Golden in Military Service Pension (MSP) application of Seamus Moran (20 September 1937). Ref. MSP34REF10227, p. 25

[15] Testimony of Seamus Moran in front of Advisory Committee (26 November 1937). Ref. MSP34REF10227, p. 37

[16] Letter from Sean Golden in MSP file of Seamus Moran (20 September 1937). Ref. MSP34REF10227, p. 25

[17] Testimony of Seamus Moran in front of Advisory Committee (26 November 1937). Ref. MSP34REF10227, p. 40

[18] ibid

[19] Joseph Kinsella (Bureau of Military History Witness Statement no. 476), pp. 15-17

[20] Statement of Louis McDermott in support of his MSP application (24 March 1927). Ref. 24SP11770, p. 44

[21] Letter from Frank Lee in support of Martin Wallace’s application for a Service (1917-21) Medal (14 February 1963). Ref. MD33913.

[22] ibid

[23] Statement by Martin Wallace in support of his application for a Service (1917-21) Medal. Ref. MD33913

[24] Cecil Nolan (24SP4989), p. 36; Michael J. Kelly (MSP34REF10226), p. 139

[25] Letter from Cecil Nolan in support of his MSP application (11 December 1926). Ref. 24SP4989, p. 36

[26] Statement of William J. Ahern in support of his MSP application (5 November 1935). Ref. MSP34REF16468, p. 25

[27] ibid

[28] Typed transcript of testimony given by Michael J. Kelly (15 January 1945). Ref. MSP34REF10226, p. 139

[29] Francis Fitzgerald supplied munitions and chemicals to the National Army during the Irish Civil War. He was killed in a Nazi air raid on his chemical works in Union Street, Stratford in June 1941.

[30] Testimony of Michael J. Kelly in front of the Advisory Committee (15 March 1937). Ref. MSP34REF10226, p. 74

[31] Typed transcript of evidence given by Michael J. Kelly (15 January 1945). Ref. MSP34REF10226, p. 139

[32] Statement of William J. Ahern in support of his MSP application (5 November 1935). Ref. MSP34REF16468, p. 25

[33] ibid

[34] Typed transcript of evidence given by Michael J. Kelly (15 January 1945). Ref. MSP34REF10226, p. 139

[35] The Scotsman, 16 August 1921

[36] Letter from Cecil Nolan in support of his MSP application (11 December 1926). Ref. 24SP4989, p. 37

[37] Testimony of Michael J. Kelly in front of the Advisory Committee (15 March 1937). Ref. MSP34REF10226, p. 74; Typed transcript of evidence given by James O’Donovan (8 February 1945) in support of MSP application of Michael J. Kelly. Ref. MSP34REF10226, p. 75; p. 157

[38] Letter from Cecil Nolan in support of his MSP application (11 December 1926). Ref. 24SP4989, p. 36

[39] The West London Observer, 19 August 1921

[40] ibid

[41] Evidence given by Lillian Manderson on 15 August 1921, Southwark Inquest Court; Report from William Brown (Divisional Detective-Inspector) of Blackheath Road police station dated 17 August 1921 included in Southwark Inquest Court file.CLA/042/IQ/02/03/004/098 (Photocopy of inquest supplied by Brian Smith)

[42] Statement of Mrs. Manderson, 15 August 1921 included in Southwark Inquest Court file.CLA/042/IQ/02/03/004/098 (Photocopy of inquest supplied by Brian Smith)

[43] The Irish Independent, 04 August 1921

[44] Letter from Cecil Nolan in support of his MSP application (11 December 1926). Ref. 24SP4989, p. 36

[45] The Irish Examiner, 16 August 1921

[46] Letter from Cecil Nolan in support of his Disability Pension application (7 March 1925). Ref. 4P1197, pp. 46-47. Lead file 24SP498.

[47] The Manchester Guardian, 02 August 1921

[48] ibid

[49] Nolan implied that “police activities” (and not a lack of beds) was the reason for changing hospital in a letter in support of his MSP application (11 December 1926). Ref. 24SP4989, p. 36

[50] The Kentish Mercury, 05 August 1921

[51] Michael McInerney, death certificate (29 July 1921), https://www.gro.gov.uk

[52] The West London Observer, 23 September 1921

[53] Information from email from historian Brian Smith to author, 15 January 2019

[54] Letter from Cecil Nolan in support of his MSP application (11 December 1926). Ref. 24SP4989, p. 36

[55] Director of Chemicals report (1 August 1921), P7/A/23 (Mulcahy Papers, UCD Archives) (Transcript kindly supplied by Brian Hanley)

[56] The Manchester Guardian, 02 August 1921

[57] Also spelt Richard Bell in some newspaper accounts

[58] The haul included 1,500 exploded homemade bombs, one Webley revolver, one old German revolver, part of a Lewis gun and material relating to the manufacture of explosives (copper wire, lids etc.)

[59] The Daily Herald, 19 September 1921

[60] Report from William Brown (Divisional Detective-Inspector) of Blackheath Road police station dated 8 August 1921 included in Southwark Inquest Court file. CLA/042/IQ/02/03/004/098 (Photocopy of inquest supplied by Brian Smith)

[61] The Irish Examiner, 16 August 1921

[62] The Pall Mall Gazette, 29 June 1922

[63] Typed history of IRA’s Chemicals Department in MSP file of Michael J. Kelly, MSP34REF10226, p. 37

[64] See MSP application of Michael J. Kelly, MSP34REF10226

[65] See MSP application of Cecil Nolan, 24SP4989

[66] Typed history of IRA’s Chemicals Department in MSP file of Michael J. Kelly, MSP34REF10226, p. 37

[67] A National Army Lieutenant Commandant named Edward Cregan from Newcastle West, County Limerick was killed on 20 August 1922 at Kanturk, County Cork but his MSP file (2D37) contains no information that he had any IRA service anywhere outside Limerick. See also short biography of this Edward Cregan in James M. Roche (BMH WS 1225), p. 22.

[68] Also spelt MacLeod in some newspaper articles

[69] The Daily Herald, 30 June 1922

[70] The police found two automatic pistols, two Martini-Henry rifles with Morris tubes, an incendiary bomb, five live pistol cartridges and 56 blank pistol cartridges.

[71] JH MacDonnell represented many IRA members who were arrested in Britain during the period

[72] The West London Observer, 30 June 1922

[73] ibid

[74] ibid

[75] The Pall Mall Gazette, 29 June 1922

[76] David Foxton, Revolutionary lawyers: Sinn Féin and crown courts in Ireland and Britain, 1916–1923, (Dublin, 2008), p. 343

[77] Gerard Noonan, The IRA in Britain, 1919-1923: In the Heart of Enemy Lines (Liverpool, 2014), p. 315

[78] ‘Deportations to Ireland’ (House of Commons, 19 March 1923) https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/written-answers/1923/mar/19/deportations-to-ireland, accessed 17 May 2019

[79] MS 8432/37, Art O’Brien Collection, National Library of Ireland (NLI)

[80] MS 8438/11, Irish Deportees (Compensation Tribunal) 17 January 1924, Art O’Brien Collection (NLI), p. 106

[81] Ibid, p. 101

[82] Ibid, p. 107

[83] Ibid, p. 95

[84] Ibid, p. 95

[85] Ibid, p. 104

[86] Martin McInerney death certificate (13 November 1923), https://www.gro.gov.uk

[87] National Probate Calendar (1924), p. 250

[88] The Irish Independent, 17 November 1923

[89] MS 8438/11, Irish Deportees (Compensation Tribunal) 17 January 1924, Art O’Brien Collection (NLI); The Irish Independent 23 January 1924

[90] Report on Sean O’Mahony, UK National Archives, HO 144/4645, p. 15. Digitised by ‘Find My Past’.

[91] An Phoblacht, 17 August 1929

[92] An Phoblacht, 03 August 1929

[93] An Phoblacht, 17 August 1929

[94] Mary Donnelly, The Last Post (Dublin, 1932), p. 71. Michael McInerney was omitted from the 1972 updated/revised edition.

[95] London Battalion IRA Nominal Rolls, Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) RO/605, p. 20

[96] An tÓglach, Vol. 1, No. 2 Autumn 1966, p.4

[97] The Nenagh Guardian, 22 August 1953

[98] The Irish Independent, 08 August 1957

[99] The Irish Press, 05 August 1959

[100] The Irish Press, 01 September 1958

[101] The Irish Press, 02 August 1947

[102] The Irish Independent, 23 November 1957

[103] The Irish Independent, 06 August 1962

[104] The Irish Independent, 09 August 1967

[105] The Irish Independent, 13 September 1968

[106] The Irish Independent, 26 July 1969

[107] The Irish Independent, 30 December 1948

[108] Description of Foundation Mass, http://www.dioceseofbrentwood.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Finance-FAQ.pdf, accessed 17 May 2019

[109] The Irish Post, 08 August 1998

[110] The Independent, 3 January 1997 https://www.independent.co.uk/news/75-years-of-bombs-and-blunders-1281346.html, accessed 17 May 2019

[111] Peter Hart, ‘Operations Abroad’: The IRA in Britain, 1919-23, The English Historical Review, Vol. 115, No. 460 (February, 2000), pp. 71-102

[112] Gerard Noonan, The IRA in Britain, 1919-1923: In the Heart of Enemy Lines (Liverpool, 2014), pp. 206; 307