Henry Hugh Tudor – His Life and Times

By Sean William Gannon

May 2020 marks the centenary of one of the most lamentable appointments in modern Irish history, that of Major-General Henry Hugh Tudor as ‘police advisor’ to the viceroy on 15 May 1920.

Four days previously, the British Cabinet had decided that ‘a special officer, with suitable qualifications and experience’ was now required ‘to supervise the entire organisation’ of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the Dublin Metropolitan Police and the war secretary, Winston Churchill, recommended Tudor for the job.[1]

Imperial soldier

But Tudor, a clergyman’s son from Devon, had no policing experience. He was in fact a life-long soldier who had made a successful army career. On leaving the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich in 1890, he was commissioned into the Royal Horse Artillery, serving first in India and then in South Africa during the period of the Second Anglo-Boer War: he was severely wounded at the Battle of Magersfontein in December 1899 but recovered well enough to return to duty. He was subsequently stationed in Britain, India, and Egypt.

Tudor, chief of police during the Irish War of Independence, had served for over 30 years in the British Army.

Tudor served on the Western Front during the Great War, commanding the artillery of the 9th (Scottish) Division and earning a reputation as a military tactician: he pioneered the use of smoke shells for screening and was one of the first proponents of predicted artillery fire. He held command of the division from March 1918 until it was disbanded in March 1919, and was ultimately promoted to the rank of major-general.

Tudor saw more service in India and Egypt before his May 1920 appointment to Ireland.

It is generally accepted that his chief qualification for the position of ‘police advisor’ in Ireland was his close friendship with the war secretary, Winston Churchill, forged during shared army service in India in the mid-1890s. Indeed, writing to Churchill in September 1923 when he was serving in another Churchill-secured role, he acknowledged that he would ‘probably have been on half pay long ago for a considerable time instead of having three or more interesting years’ had it not been for his friend’s interventions.[2]

‘Chief of Police’

Tudor, who following the retirement of RIC Inspector-General T. J. Smith in November 1920, styled himself ‘chief of police’, saw his task in Ireland as nothing less than the restoration of law and order through a revitalized police operation.

In his view, ‘the whole country was intimidated [by Sinn Féin] and would thank God for strong measures’ and he proposed, amongst others, the blanket introduction of identity cards, communal punishments such as fines, the replacement of civil courts with courts martial, and the deportation of republican prisoners.

He also recommended flogging for hair cutting and other ‘outrages against women’ and the purging of the Irish Post Office of ‘traitors’.[3]

As the then flailing RIC was clearly inadequate to the task Tudor set it, he embarked on a programme of militarization aimed at boosting its counterinsurgency capability and force morale – replacing the force’s obsolete weaponry with more modern issue, restructuring its feeble intelligence service, improving coordination with the military, and appointing old soldiers to senior roles.

The Auxiliary Division of the RIC, responsible for many of the most notorious atrocities of the period, was largely Tudor’s brainchild.

Most notably, he installed Brigadier-General Ormond de l’Épée Winter (an old army friend) as head of intelligence and deputy chief of police. The centrepiece of Tudor’s plan to reinvigorate the police counterinsurgency was the formation of the Auxiliary Division of the RIC (ADRIC), a 1,500-strong gendarmerie-style striking force composed of demobilized British officers. Introduced in summer 1920, 17 companies between 80 and 100 men-strong were deployed to areas of significant insurgent activity where, well armed and highly mobile, they tried to root out and neutralize the local IRA.

Tudor’s militarization of the RIC indeed proved calamitous. Within six months of Tudor’s appointment, the force was internationally notorious, particularly the ADRIC which, while operating quasi-autonomously, remained under nominal RIC command.

In May 1920, chief of the imperial general staff, Sir Henry Wilson, denounced Tudor’s plan for the force as ‘truly a desperate and hopeless expedient … bound to fail’ and his prediction that it would inevitably have ‘no discipline, no esprit de corps, no cohesion, no training’ proved prescient.[4] The Auxiliary Division went on to commit the most infamous crimes of the entire revolutionary period (for example, the torture and murder of the Loughnane brothers, the shooting of Ellen Quinn and Fr Griffin, the burning of Cork, and the Limerick ‘Curfew Murders’) with what appeared to be Tudor’s tacit support.[5]

For while paying lip-service to the requirement for police discipline and criticizing property destruction and reckless, wild fire, he adopted a conspicuously lenient approach to reprisals, which shaded into what assistant undersecretary at Dublin Castle, Mark Sturgis, termed ‘passive approval’ at certain times.[6]

Most notoriously, Tudor reinstated 21 Auxiliaries dismissed by ADRIC commander Frank Crozier in consequence of a looting and burning in Trim, resulting in Crozier’s resignation. Tudor was, however, also constitutionally blind to bad police conduct.

As Sturgis observed in January 1921, ‘he does not consciously deceive but his belief in all that’s good of his Black and Tans and his inability to believe a word against them is superhuman’.[7]

By spring 1921, Tudor had lost the confidence of both the general officer commanding in Ireland, Nevil Macready (to whom Tudor effectively reported although, technically, he outranked him) and Sir Henry Wilson who, in March 1921, wrote in his diary: ‘I am certain that Tudor, Winter and a whole crowd of those wild devils ought to be packed off’.[8]

Tudor’s failure to appreciate the conflict’s political context lost him the confidence of the government in London as well. Thus, Wilson spoke for most on the British side when he appraised Tudor as ‘a gallant fellow on service, but a man of no balance, knowledge or judgement and therefore a deplorable selection for his present post’.[9]

Tudor’s post was abolished in consequence of the RIC’s disbandment in 1922 and he once again required work. Once again his friend Churchill obliged. Churchill was now secretary of state at the Colonial Office, the Middle East Department (MED) of which bore full responsibility for the recently acquired Palestine Mandate.

Palestine

The rationalization of the territory’s security forces was a policy priority at the time, Churchill’s scheme to effect this focussed on the reduction and ultimate removal of its expensive British Army garrison, and the contingent boosting of its civil policing services.

The centrepiece of this scheme was the raising and deployment of a striking force/riot squad to assist the locally recruited Palestine Gendarmerie and Palestine Police forces maintain public order.

This new British Section of the Palestine Gendarmerie (British Gendarmerie), overwhelmingly recruited from RIC sources in spring 1922, was supported by Indian troop units and the Royal Air Force (RAF) which the Colonial Office believed had demonstrated the efficacy and cost-efficiency of air policing during the anti-British rebellion in Mesopotamia in 1920.

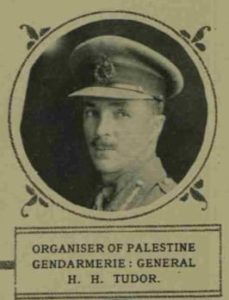

After the RIC was disbanded, Tudor served for two years as commander of the British Gendarmerie in Palestine.

Churchill first considered Tudor for the position of Palestine’s general officer commanding. But with primary responsibility for public order being devolved onto the territory’s civil forces, his appointment as director of the department of public security, giving him control of the Palestine Police and both gendarmeries, appeared a more appropriate choice.

In the event, Churchill decided to combine the two posts and install his friend at the helm: Tudor was appointed General Officer Commanding (with the rank of Vice Air Marshal) and Inspector-General of Police and Prisons (GOC-IPP) in February and ‘assumed command of all forces, civil and military, employed on imperial defence and internal security in Palestine in [this] dual capacity’ on 15 June 1922.[10]

As with his placement as ‘police advisor’ in Ireland, this appointment has been criticized by historians as patronage at its worst – both posts paid a handsome £3,300 gross salary per year and Tudor’s service in both Ireland and Palestine counted towards qualification for a major-general’s pension.

Yet, there was agreement among officials in the Middle Eastern Department (MED) that Tudor was the ideal choice for the job. According to its assistant secretary, Hubert Young, he was ‘a really capable and experienced soldier who knows all about police work’, and its military advisor, Richard Meinertzhagen agreed, advising Churchill that Tudor’s ‘knowledge of Arabic, his experience of police work, his military record – make him peculiarly fitted for the post’, not to mention that fact that he was ‘familiar with the new [British] Gendarmerie, they are practically his own child and they know and understand him’.[11]

Tudor had learned Arabic while serving in Egypt and passed a first-class interpreter’s examination in the language, an important consideration for Palestine where, with few exceptions, the British security forces were entirely ignorant of the vernaculars. Tudor also, as Meinertzhagen pointed out, knew the British Gendarmerie well.

He had devised, recruited, and organized, and (prior to embarkation for Palestine) administered the force and he was personally and professionally acquainted with many of its officers and men. During a series of valedictory inspections of detachments of disbanding RIC in March and early April 1922, Tudor made a point of saying that he looked forward to meeting some of them again in Palestine.[12]

He was not well regarded by the British civil administration in Palestine.

However, MED officials quickly repented of their support for Tudor’s candidature. For although eminently suitable on paper, Tudor proved ill-suited to the job – he being an intensely difficult man with whom both subordinates and superiors found it extremely challenging to work. This was particularly evident in respect of his dealings with the British Gendarmerie, which he so regarded as the mainstay of public security in Palestine that he devoted much of his energy micromanaging the force’s affairs.

He maintained generally difficult relations with its commandant, Brigadier-General Angus McNeill, as a consequence, exacerbated by the fact that McNeill had not been Tudor’s choice for the job. Tudor had strongly recommended the appointment of Ormond Winter but the latter was deemed wholly unsuitable by the MED, on probable account of his unorthodox professional style which had divided opinion in Dublin Castle, during Winter’s time as head of intelligence in Ireland.

Just two months after Tudor’s arrival in Palestine on 22 June, McNeill was complaining of his short temper and general irascibility, and an impetuous nature which saw him ‘continually starting wild cat schemes without due consideration’.[13] One year later, he was denouncing him as ‘quite the worst commander I have ever served under’ – so dictatorial, capricious, and ‘hopeless at administration’ that ‘if he remains in command either I shall be under arrest for mutiny or he will be murdered by one of his own Black and Tans’.[14]

Tudor’s own superiors in the Colonial Office and Air Ministry found him equally difficult. His outright refusal properly to manage his dual GOC-IPP role was their particular bane. Churchill had instructed Tudor on his appointment to keep ‘his military and civil functions … entirely separate … and discharged through separate channels’, but Tudor wilfully blurred the distinction entirely.[15]

This was particularly pronounced in the case of the British Gendarmerie which, although semi-military in character, formed part of Palestine’s civil forces. Yet Tudor administered it through his military staff and addressed all correspondence on matters pertaining to the Air Ministry rather than the Colonial Office.

One month after his arrival in Palestine, he was asked by RAF chief Hugh Trenchard to desist from this practice. Yet he persisted to the fury of both departments, Air Ministry officials coming to believe that he had had a policy of obeying its orders only when it suited his purposes. MED official Gerard Clauson attributed Tudor’s obnoxious behaviour to his sheer inability as a seasoned soldier ‘to think along civil lines’.

The fact that Ireland was a war-zone and the RIC a military force during the entire period of his command there meant that he had no idea how an ordinary police force was administered, and consequently ran the British Gendarmerie ‘on the same lines as the Auxiliary Division in Ireland, that is on military lines’.[16]

Nine months later, he complained that Tudor was still treating orders given by the civil authorities ‘with disrespect whenever it [suited] him to do so’, particularly the Palestine government of high commissioner Sir Herbert Samuel, towards which was ‘constantly adopting an attitude of independence’.[17]

‘I am not ever going to return’: the abrupt end of Tudor’s marriage

Tudor’s standing with Samuel himself was further undermined by the manner in which he conducted his personal affairs. Tudor had married Eva Edwards in 1903, and their children (a son and three daughters) were born between 1905 and 1913. But he had endured long periods of separation from them on account of Tudor’s military career. Although Lady Tudor had been either unwilling or unable to join him in Ireland, she fully intended to accompany him to Palestine, but delayed her departure due to the death of her father.

Tudor’s wife Eva travelled to Palestine but he refused to see her and then demanded a divorce, scandalizing many of the British community there.

Shortly afterwards, however, Tudor demanded that she divorce him, which evidently came as a great shock, for she refused, insisting that she would join him in Palestine instead. Despite Tudor’s instructions that she remain in England, she travelled to Palestine in February 1923 to end to what she described as their ‘absurd estrangement’.

Tudor, who had her travelling facilities stopped at Kantara, initially refused to see her but finally relented, only to reissue his demand for a divorce which, once again, she rejected. Tudor refused to cohabit with her on a visit home to England in April writing: ‘I want you to understand clearly, that I am not going to ever return in any circumstances. Neither will I consent to receive you here [in London] or in Palestine’. This led Lady Tudor to successfully apply for a decree of restitution of conjugal rights (a legal ruling compelling a married couple to live together again) which Tudor ignored.

Although the couple now effectively separated, they never divorced, and legal wrangles over maintenance payments continued for years.[18] Tudor’s personal difficulties were widely reported in the British press and became grist to Jerusalem’s gossip mill after what McNeill referred to as Lady Tudor’s ‘rather mysterious visit’ to the country in 1923.[19]

Samuel, described by his son as having ‘ideas of morality in general [that] were puritanical in the extreme’, was thoroughly scandalized by Tudor’s behaviour and gradually withdrew his support for him.[20]

So unwanted a presence did Tudor become that it was decided to terminate his employment under the cover of abolishing his post. Tudor ‘retired’ as GOC-IPP in March 1924, McNeill speaking for most people in Palestine when wrote in his diary after seeing him off: ‘I never wish again to serve under such a man. He has been no use to us officially or socially since he dropped out of the clouds … twenty-one months ago’.[21]

In keeping with form, Trenchard thanked Tudor on announcement of his retirement for making the Air Ministry’s task ‘in running a new responsibility’ in Palestine ‘as easy as possible’ and Tudor left Palestine unaware of his poor reputation.[22]

To his mind he had, despite insufficient resources, made a considerable success. His ‘own child’, the British Gendarmerie, had ensured inter-communal quiet between Arabs and Jewish settlers, while the serious problem of brigandage was finally being taken in hand.

Moreover, Tudor had very much enjoyed his time there. Palestine was, Tudor told Churchill, a ‘rest cure after Ireland’, giving him time to indulge his twin passions of photography and flying: he took flying lessons in a Bristol F2B and accumulated over 100 hours of flight time during his 21 months there.[23]

In the course of his service in Palestine, he was also knighted, in 1923 (KCB on the New Year’s Honours List).

Retirement in Canada

On leaving Palestine, Tudor returned to Britain. He retired from the army in March 1925 and emigrated to Newfoundland in November where he lived out the rest of his life. It has been suggested that this move was prompted by fears for his safety: according to his biographer, he had continued to receive death threats after leaving Ireland in 1922 and it has been suggested that he believed himself to be still under IRA interdict three years later.[24]

Certainly, Tudor them took IRA threats seriously, especially subsequent to the June 1922 murder of Sir Henry Wilson outside his London home. (“Sir Henry’s was the name at the top of the so-called Death List. General Tudor’s came next”).[25]

Tudor retired to Newfoundland where he lived the rest of his life. It was rumoured that the IRA tried to assassinate him in the 1950s

But evidence has yet to emerge that he remained under threat, apart from the rather fanciful story of an abortive attempt on his life many years later in Newfoundland recounted by Tim Pat Coogan, citing mysterious ‘sources of [his] own’. According to Coogan, two would-be IRA assassins were dispatched to Newfoundland to kill him but decided to make confessions prior to the murder; the priest dissuaded them from carrying it out and they made their way back to Ireland.[26]

Whatever the truth of this tale, Tudor’s reasons for relocating to Canada were probably more prosaic in nature. First, he desired to move on from his family and, indeed, the scandal in which his abandonment of it had resulted. Secondly, he saw no employment prospects in Britain.

As he told Churchill when news of his removal from Palestine came through, there were few military vacancies suitable for a soldier of his rank and it was ‘not too easy to find a job even in civil life’ either.[27] The fact that he lived openly in Newfoundland – his address and number were listed in the telephone directory – further suggests that the move was not motivated by fears for his safety and he regularly returned to Britain in the interwar years.

Tudor worked as a fish buyer in Newfoundland, first for Ryan & Company in Bonavista, and subsequently for George M. Barr, a successful English fish exporter based in St John’s and a man with whom he developed a close friendship.

Tudor also moved easily in the city’s ‘loyal’ social circles. He was a regular guest at the British governor’s house and was introduced to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth when they visited St John’s in June 1939. (According to one local history, the King asked him if he was the Tudor of Black and Tan (in)fame, much to the general’s embarrassment).He was also an active member of the local sports scene, enjoying boxing, horse racing, polo, and golf.

Tudor suffered significant ill-health in later years (including the loss of his sight) and was cared for by his long-time companion, an Irish Catholic named Monica McCarthy.

He died in the veterans’ pavilion of St John’s General Hospital on 25 September 1965, aged 94 and was buried with full military honours provided by the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, a component of his old 9th Scottish Division.

References

[1] According to Sir Henry Wilson, Churchill first choice for the post was actually Dubliner, General Sir Edward Bulfin, but he turned it down. D. M. Leeson, The Black and Tans: British police and auxiliaries in the Irish War of Independence (Oxford, 2011), 32; Imperial War Museum (IWM), Sir Henry Wilson collection, Diaries: 28 Mar. 1921.

[2] Churchill College, Cambridge, Churchill papers (CHAR) 2/126/43, Tudor to Churchill, 21 Sept. 1923.

[3] British National Archives (TNA), Cabinet papers, CAB 24/109/26.

[4] Charles Townshend, The Republic: the fight for Irish independence (London, 2013), p. 139.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Michael Hopkinson (ed.), The last days of Dublin Castle: the Mark Sturgis diaries (Dublin, 1999), p. 95.

[7] Ibid., p. 110.

[8] IWM, Henry Wilson diaries: 16 Mar. 1921.

[9] Ibid, 28 Mar. 1921.

[10] ‘Report on Palestine Administration, 1922’ (London, HMSO, 1923), 38.

[11] TNA, Colonial Office files (CO) 733/18/397, Young to Shuckburgh, 13 Feb. 1922; TNA, CO/733/18/406, Meinertzhagen, ‘Draft note to Secretary of State’, 22 Feb. 1922.

[12] Irish Times, 5 Apr. 1922.

[13] Middle East Centre Archive, Oxford (MECA), Angus McNeill collection, Diaries: 15 Aug. 1922.

[14] MECA, McNeill Diaries: 10 Aug., 26 Nov. 1923.

[15] TNA, CO/733/19/335, Churchill, Memorandum on Tudor’s appointment, undated, Feb. 1922.

[16] TNA, CO/733/29/403-4, Clauson, Colonial Office minute, 26 Dec. 1922.

[17] TNA, CO/733/48/188, Clauson, Colonial Office minute, 13 Sept. 1923.

[18] Quotations from correspondence in TNA, J77/1990/2359, ‘Divorce Court file 2359: Tudor v Tudor’.

[19] MECA, McNeill diaries: 15 February 1923.

[20] Edwin Samuel, A lifetime in Jerusalem (London: 1970), p. 8.

[21] MECA, McNeill diaries: 30 Mar. 1924.

[22] RAF Museum London, Trenchard collection, MFC76/1/285, Trenchard to Tudor, 21 Nov. 1923.

[23] RAF Museum, Trenchard collection, Tudor to Churchill, 1 Oct. 1922.

[24] IWM, Misc. 175/2685, Joy Cave, A gallant gunner general: the life and times of Sir H. Hugh Tudor, K.C.B., C.M.G., pp 326.

[25] Ibid., p. 327.

[26] Tim Pat Coogan, Wherever green is worn: the story of the Irish Diaspora (London, 2000), p. 416.

[27] Churchill College, CHAR/2/126/43, Tudor to Churchill, 21 Sept. 1923.