The Battle of Fontenoy in Irish Nationalist Tradition

By Stephen McGarry

May, 2020 marks the 275th anniversary of the Battle of Fontenoy (1745) which took place during the War of the Austrian Succession between France and an English-led coalition in modern-day Belgium.

The actions of the Irish Brigade of France there are generally regarded as being the pinnacle of Irish military prowess.

The Duke of Cumberland’s Anglo-Hanoverian infantry were at the cusp of victory, when the French commander, Maurice de Saxe sent in six infantry regiments of the Irish Brigade of France at the last minute to halt the Allied advance. The Irish charge smashed violently through the English foot and secured victory for France.

The Irish Brigade in French service helped to defeat the British Army of the Duke of Cumberland at Fontenoy, in modern Belgium in 1745

The battle of Fontenoy, fought at the height of the anti-Catholic Penal Laws in Ireland, was looked upon with ferocious pride back home in Ireland. Among other things, the Penal Laws forbade Catholics from bearing arms and serving in the military, and thousands of Irish Catholics, nicknamed the ‘Wild Geese’ were recruited into military service with the Catholic powers, principally France and Spain in the first half of 18th century.

The British defeat was deemed as vengeance for the Catholic or Jacobite defeat in the Williamite War and the broken 1691 Treaty of Limerick – the terms of surrender had guaranteed civil and religious rights for Catholics, a promise subsequently disowned by the Protestant dominated Irish Parliament. The Irish Catholic victory over their oppressors at Fontenoy loomed large in the Irish psyche for many years afterwards.

The memory of the battle was even adopted by Protestant Irish nationalists such as the United Irish leader Theobald Wolfe Tone as an example of Irish bravery in arms.

‘Irish valour’

Wolfe Tone recalled Irish valour at Fontenoy in his memoirs. Miles Byrne, who served in Napoleon’s Irish Legion, mentioned an occasion in 1810 when the French commander called on them to remember Fontenoy, prior to the Battle of Bussaco against the Duke of Wellington’s Anglo-Portugese army during the Peninsular War.

Thomas Francis Meagher, who had fought in the 1848 Irish Rebellion, raised an Irish brigade from Irish-Americans in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Meagher also famously rallied his troops with ‘Remember Fontenoy!’ prior to their charge at the battle of Bull Run in 1861.

Irish valour at Fontenoy was proudly celebrated in stories, poems and songs and incorporated into the Irish nationalist tradition.

Irish valour at Fontenoy was proudly celebrated in stories, poems and songs. During the nineteenth century, Thomas Davis’s ‘The Battle of Fontenoy,’ ‘The Battle Eve of the Brigade’ and J.C. O’ Callaghan’s magnum opus; ‘Irish Brigades in the Service of France,’ in particular, helped to establish the cult of the Wild Geese in Irish nationalist tradition.

The exploits of the Wild Geese captured the romantic imaginations of many Irish writers in the early twentieth century, notably the poet Emily Lawless and Arthur Conan Doyle. MIchael O’Hanrahan, who was executed after the 1916 Rising, penned ‘Swordsman of the Brigade,’ a novel about the adventures of a soldier in the Irish Brigade of France during the early 18th century.

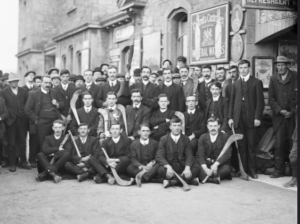

There were streets and GAA clubs named after the battle. James Joyce, for example, lived for a time in Fontenoy Street, in Dublin 7. Clanna Gael Fontenoy GAA Club recently visited the Fontenoy cross, from whence the club takes its name. This is perhaps fitting, as two years after the battle, a hurling match was played on the battlefield by the Irish Brigade in memory of their fallen comrades.

The Fontenoy Committee of 1905

In 1904, the founding member of the Irish Literary Society in London, Richard Barry O’Brien was touring Belgium and stopped off at the village of Fontenoy. The village had changed little since the battle.

It was described at the time as being a scattered village of twenty or thirty modest, single-story, red roofed cottages with a brick church in its centre. Upon his return to Ireland, O’Brien proposed that an official trip should be made to Fontenoy to remember the fallen Irish.

The idea gained the support of the Lord Mayor of Dublin and a ‘Fontenoy Committee’ was established with a view to conducting an official ‘pilgrimage’ to Fontenoy the following year. The preparations for which were regularly reported in the Freeman’s Journal and in other nationalist papers.

In the early 1900s, Irish nationalists erected Celtic Cross at Fontenoy and led numerous expeditions there to commemorate the battle.

In June 1905, a large Irish entourage – according to the Irish Independent numbering three-hundred people – travelled to Belgium. Among the eminent visitors were John McBride, who would be later executed following the 1916 Rising, he had recently fought with the Boers in South Africa and had organised an Irish Transvaal brigade there to fight the British.

The elderly Fenian leader John O’ Leary and Patrick Pearse were also present along with Richard Barry O’Brien, and the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Joseph Hutchinson. The Irish were warmly received by the Bourgmestre of Tournai, along with other representatives, and following a religious service in Irish by Father McInerney in Tournai, the entourage travelled the 10km to the historic battlefield of Fontenoy.

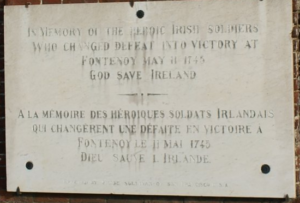

It was felt that a proper monument to the Irish should be erected, as the only memorial displayed at the time was a white marble plaque on the wall of Fontenoy’s graveyard. It was erected by Frank Sullivan in 1902, an Irishman living in San Francisco, which reads in English and in French. ‘In memory of the Irish soldiers who changed defeat into victory at Fontenoy, May 11, 1745. God save Ireland.’

Two years later, the Irish Literary Society had raised sufficient funds by public subscriptions in Ireland, Britain and America to finance a memorial. The Dublin-based architect Anthony Scott from Co. Sligo was commissioned for the project.

Scott designed a five-metre Celtic cross, the base of which was hewn out of rough Irish grey granite on a plinth of Limerick marble and the cross was sculpted out of blue Kilkenny granite. The initial site for the monument was to be in the nearby city of Tournai, but due to initial anti-clerical opposition by the inhabitants there to the erection of a cross, the proposed location was changed to Fontenoy.

The cross travelled from Dublin by sea to the Belgian port of Antwerp, from there it was placed on a train to Tournai and hauled onto a horse drawn cart to its inauguration site at Fontenoy’s village green. In August of 1907, Anthony Scott arrived in Fontenoy to oversee the project together with his Dublin firm of building contractors. The Thompson brothers dug foundations, erected wooden scaffolding and began assembling the cross, and in no time, the three-piece cross was hoisted and cemented into position.

The cross’s inscription, written in French and Irish, was dedicated to the Irish Brigade who avenged the violation of the 1691 Treaty of Limerick. Carved into the base of the cross’s base is a relief of the Treaty of Limerick stone, with an inscription written in Irish.

‘On this stone was signed the treaty by which England should have granted religious freedom to the Irish people. It broke that treaty and the Irish, driven from their homelands, enrolled in the French armies and won fame on the battlefields of Europe.’

These were strong words, indeed, but Irish memories are long.

On August 25th, 1907, the monument was proudly unveiled by the newly-elected Lord Mayor of Dublin, Joseph Nannetti, President of the New York Committee J.Grimmins, Richard Barry O’Brien of the Irish Literary Society and the Bourgmestre of Tournai, amid much fanfare.

A religious service followed before the entourage attended a ’Banquet Commémoratif des Irlandais’ at the upmarket Hotel des Neuf Provinces in nearby Tournai. The sumptuous meal was washed down with crates of fine French wines and by locally brewed, strong trappist beers.

Many thumping, rebel rousing ballads and bellicose speeches, one supposes, completed the evening. There were many sore heads, no doubt, when the entourage boarded the train the next morning on their long journey back to Calais, and onwards back home to Ireland. The inaugural event had proved to be a resounding success.

Fontenoy firmly established

The memorial firmly established Fontenoy as a stop-over point for Irish tourists tracing Irish footprints on the Continent. In 1910, a game of hurling between Tipperary and Cork was played at Fontenoy, organised by the Pan-Celtic Congress which was being held in the Belgian city of Namur at the time.

The players reportedly arrived with leaflets written in French, Irish and English describing the game, while the local school children impressed them by singing the unofficial Irish national anthem ‘God Save Ireland’ in French.

The cross, located close to the Western Front, luckily survived the bombardment of the First World War. The 16th (Irish) Division of the British Army, by a strange coincidence, was serving on the historic battlefield of Fontenoy at the time of the armistice on Nov 11th, 1918 and halted there when the hostilities ceased. The memorial also luckily emerged out of the Second World War unscathed.

The Irish State takes charge of the monument

In 1947, William Fay, Ireland’s chargé d’affaires in Brussels, was requested by the Department of External Affairs to inspect the Fontenoy cross. Fay reported back that the villagers appeared to be proud of their monument and he met an old woman there who recalled the unveiling of the cross.

Fay was told that the local children are still taught Irish songs and commemorate the battle at the cross every year on May 11th. He recommended that the Irish Government take charge of the monument, arguing, rightly, that Fontenoy was one of the few glorious moments in our ‘long’ eighteenth century.

The monument is now under the care of the Office of Public Works, renovation works to the value of 20,000 euro have been completed on it in 2014, and the cross proudly takes part in the annual Global ‘greening’ initiative for St. Patrick’s Day.

The monument is now under the care of the Irish Office of Public Works

The quiet village of Fontenoy, located in the province of Hainaut in French-speaking Belgium, has a population today of just over 700 people, and probably hasn’t changed that much since 1905. However, unlike Waterloo, located less than 100km due east, the battlefield at Fontenoy has changed a great deal.

The local sugar refinery occupies part of the battle site, while the A16 motorway linking Tournai to Mons cuts right through the field of battle, but the cross survives.

Today, the locals continue to remember the Irish dead by raising the Irish tricolour on the monument on May 11th. The local historic military association of Le Tricorne, and of Fontenoy 1745, seek to perpetuate the memory and raise awareness of the battle through conferences, exhibitions, guided tours, publications and exhibitions.

Commemorations

On the battle’s 250th anniversary in 1995, Defence Forces personnel, along with representatives from France, Belgium and England, took part in a wreath laying ceremony at the memorial. A game of hurling was organised by the historian and president of the Gaelic Sports Club of Luxembourg, Eoghan Ó’hAanracháin, who has written extensively about the Wild Geese.

The Belgian and Irish Post Offices also issued a joint stamp depicting two officers of Clare’s and Dillon’s standing beside the Celtic cross.

A commemorative event at Fontenoy marked the 260th anniversary, with a reading of Davis’s poem ‘Fontenoy’ and with bag-pipers playing; ‘The White Cockade,’ followed by a welcome in the local Café des Irlandais and a civic reception in the Hôtel de Ville in nearby Tournai. President Jacques Chirac sent a delegation to the French Embassy in Dublin, comprising a contingent of the Élysée Palace guards, dressed in 18th century uniform, for a special ceremony there.

An event to mark the 275th anniversary was planned for May 10th. The city of Tournai and Antoing had been coordinating commemorations for many months, with representatives drawn from Ireland, Belgium, France and Britain planned to attend.

These will sadly now not take place as the Belgian Government has prohibited all official events until the end of August due to the Covid-19, and neither will commemorations take place in Dublin for similar reasons.

This is, indeed, a great shame as the memorial has never looked better since the Thompson brothers erected it so many years ago. The memorial sits on Fontenoy’s well maintained village green, now called the Esplanade d’Irlande.

The iron railings surrounding the memorial have been repaired, the cross stabilised, and the granite and marble cleaned, with the incised lettering gilded for the first time since 1907. It is a big change from when I visited the cross a number of years ago, for it then looked sad and forlorn.

I have been reminded that this will not have been the first time commemorations at Fontenoy have been cancelled, for the bicentenary of the battle in 1945 was interrupted by the Second World War as the armistice was signed with the forces of the Wehrmacht just days earlier. There were then, bigger fish to fry. Readers, instead, may choose to commemorate the fallen on May 11th by recalling the last lines of Davis’s poem;

‘On Fontenoy, on Fontenoy, like eagles in the sun,

With bloody plumes, the Irish stand-the field is fought and won!’