Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil: ‘Civil War’ Parties?

By Dr Mel Farrell

Since the foundation of the Irish State in 1922 its politics have been dominated by two political behemoths. The modern Fine Gael party and its historic rival, Fianna Fáil, both trace their origins to the 1917-21 independence movement.

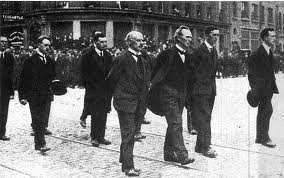

Eamon de Valera, Arthur Griffith, Michael Collins, Cathal Brugha, Austin Stack, W.T. Cosgrave and Robert Barton formed the Second Dáil’s seven member cabinet when Sinn Féin agreed to enter into talks with David Lloyd George’s government in the autumn.[1]

Every administration since the state’s first change of government in 1932 has been led by one party or the other while Cumann na nGaedheal, Fine Gael’s parent party, had governed the state through the first ten years of independence.[2]

Throughout the twentieth-century, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael remained bitter rivals, at national and local level. Each party developed and maintained an organisational presence in every constituency in the state, a factor that has surely shaped the nature of the intense rivalry between them.

Are Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael really ‘civil war parties’?

However, as politics have become increasingly fragmented in the early decades of the twenty-first century, more people have begun to question the place of these historic rivals in modern Ireland. While loyalty to ‘one colour or the other’ still runs deep in many Irish homes, the February 2020 general election was dominated by a sense that, as we enter the third decade of the new century, there is little to separate Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, with both looking to occupy the centre ground.[3]

Voters have never been less enthusiastic about the once dominant parties, reducing their combined share of the vote to its lowest ever level -approximately 43% in what has been interpreted as an attempt to create a more clear-cut left/right divide in Irish politics. Given the likelihood that the two parties will soon serve in government together for the first time, perhaps now is the time to look again at the evolution of these two parties and the ‘cliché’ of ‘Civil War politics’?

“Civil War Politics”

Although the common origins of Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil in what Michael Laffan termed the ‘second’ Sinn Féin of 1917-22 are well established, the term “Civil War politics” implies that nothing other than the Treaty split of 1921/22 separates the two parties.

It also ignores the fact that the post-Easter Rising Sinn Féin from which they evolved, was not a conventional political party with a particular socio-economic outlook. It was, rather, a coalition formed when those who identified with the Rising joined forces with Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin.

During 1917-18 the party had attracted disgruntled Home Rulers, republicans, social reformers and agrarian agitators. It came to represent a broad spectrum of views and we know from the work of Michael Laffan and the late David Fitzpatrick that the old Sinn Féin remained united by focussing on the goal of Irish independence while avoiding divisive social, economic and constitutional issues.[4]

Sinn Féin of 1917-1921 was not a conventional political party with a particular socio-economic outlook but a coalition which strove for Irish independence.

The unhelpful cliché of “Civil War politics” also discounts the fact that there were immense fluctuations in the respective pro- and anti-Treaty support levels in the decade after the Civil War. Indeed, Fianna Fáil’s and Fine Gael’s evolution as distinct entities occurred over a ten-year period, 1923-33. Fianna Fáil was established in 1926, three years after the Civil War ended, while Fine Gael was brought into being when the National Centre Party and the National Guard (the ‘Blueshirts’) merged with the original pro-Treaty party in September 1933.

The Treaty Split

The the old Sinn Féin party had split over the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, ‘signed at ten minutes past two’ on the morning of Tuesday 6 December 1921.[5] Under the Treaty, the twenty-six counties of ‘Southern Ireland’ – established, along with ‘Northern Ireland’, by the ill-fated 1920 Government of Ireland Act – would secede as an ‘Irish Free State’ from the United Kingdom as a self-governing Dominion of the British Commonwealth.

Elected members of the Free State parliament would have to recognise the British monarch as head of the Commonwealth by swearing the controversial oath while the parliament of ‘Northern Ireland’ was given the ‘Ulster month’ to decide whether to opt in or out of the proposed Free State. This compromise fell short of the thirty-two county Irish Republic desired by most Sinn Féiners, but was grudgingly accepted by the pro-Treatyites as a ‘stepping-stone’ to fuller independence. However it caused both political and military arms of the revolutionary movement to split. [6]

The Dáil government was evenly divided on the issue. Griffith, Collins and Barton backed the Treaty they had signed in London while Brugha, Stack and de Valera opposed them W.T. Cosgrave’s was to prove the decisive vote when, after a marathon five-hour meeting on 8 December 1921 the cabinet voted to recommend the Treaty to the Dáil. Cosgrave had sided with those ministers who had negotiated the settlement.[7]

Within nine months of this, arguably the most important cabinet meeting in Irish history, three of its seven members would be dead, while a fourth, reluctant signatory Robert Barton, would have switched sides. In a Dáil that was just as divided as the cabinet, the fate of the Treaty hung in the balance before passing, by sixty-four votes to fifty-seven, on 7 January 1922.

A formal split of the Sinn Féin organisation was narrowly avoided at the February 1922 Ard Fheis. As party activists traded personal insults on the conference floor, the leadership met in private where they thrashed out an agreement that would see the Ard Fheis adjourned for three months so as ‘to avoid a division of the Sinn Féin Organization’.[8]

Sinn Féin split into antagonistic factions over the Treaty

In reality, the split was underway. Within weeks, the pro- and anti-Treaty factions had formed their own political structures in anticipation of a summer election that would serve as a de facto referendum on the Treaty settlement. De Valera even gave his a name, Cumann na Poblachta which was launched in March 1922.

More ominous, however, was the deteriorating situation in the Irish Republican Army – itself divided over the Treaty. Through February, March and April the pro- and anti-Treaty factions within the army jostled for position as the British forces speedily evacuated their positions in the ‘Southern Ireland’ area.

On 14 April, the anti-Treaty IRA seized and occupied the Four Courts in Dublin city centre. As tension mounted, Collins and de Valera used their separate public appearances to warn that civil war was in the air. In an attempt to bring Sinn Féin back together for the election, the two men finally cobbled together a seven point ‘Pact’ on 20 May.[9]

Under the pact, a joint panel of candidates was selected in accordance with existing pro- and anti-Treaty Dáil strengths. It would be the last time many long-time colleagues canvassed together under the Sinn Féin banner.

With strong transfers between the pro- and anti-Treaty Sinn Féin candidates the results were: 58 Pro-Treaty TDs, 36 Anti-Treaty TDs, Labour 17 TDs and others 17 TDs. Within a week of the election, politics took a back seat as the country finally descended into outright civil war on 28 June 1922. Under pressure from the British, Provisional Government forces attacked the anti-Treatyite position in the Four Courts. Any hopes for a reunified Sinn Féin party were sundered.

Born in bitterness: Cumann na nGaedheal’s emergence

In August the pro-Treatyites were dealt a crippling blow when Griffith and Collins died within ten days of each other. After an emergency meeting that began at 4 a.m., leadership passed to W.T. Cosgrave, the most senior pro-Treatyite remaining.[10] On the anti-Treaty side Cathal Brugha was killed in action in early July while de Valera found himself an increasingly marginal figure with little influence on the republican side.[11]

After the death of Collins, the conflict became a dirty war described by the late Michael Hopkinson as something approaching ‘a vendetta on a national scale’. The pro-Treaty authorities introduced tough public safety legislation which gave military courts the power to execute persons found in possession of arms or aiding and abetting attacks on state forces.

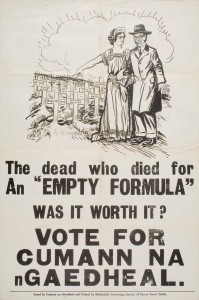

The pro-Treaty party Cumann na nGaedheal was formed at the height of the Civil War to support the Cosgrave government in building the new state on the foundations of the Treaty settlement.

On 17 November the first executions took place. In response, the anti-Treaty IRA declared that TDs or Senators who had voted for the ‘Murder Bill’ were liable to be shot. On the afternoon of 7 December pro-Treaty TDs Seán Hales and Pádraic Ó Máille were set upon by gunmen in the city centre.[12] Hales was shot dead while Ó Máille suffered extensive wounds.

Within 24 hours, the Free State retaliated by executing four prisoners as a reprisal. This was an act without any pretence of legality. All four prisoners, Joe McKelvey, Liam Mellowes, Rory O’Connor and Dick Barret were captured months prior to the enactment of the tough public safety legislation. They were executed on the morning of 8 December.[13]

On the same day as the attack on Hales and Ó Máille, their pro-Treaty colleagues had been attending a specially convened pro-Treaty conference at 5 Parnell Square. The main business of this meeting was the formation of a new party to support Cosgrave’s government. While some pro-Treatyites wished to continue under the Sinn Féin name, Ernest Blythe argued that the foundation of the state had completed Sinn Féin’s work.[14]

Instead, the pro-Treatyites named the new party ‘Cumann na nGaedheal’ in homage to another nationalist organisation formed by Griffith in March 1900. The original Cumann na nGaedheal had, of course, merged with the National Council to form Sinn Féin in 1905 so there was a strong degree of symbolism attached to it.

The new party’s mission was to support the Cosgrave government in building the new state on the foundations of the Treaty settlement. Cumann na nGaedheal had, therefore, a strong sense of the new state’s institutions and saw itself, through the 1920s, as the party that had founded the new state.

The Civil War ended, without a negotiated settlement, with the ‘dump arms’ order on 24 May 1923. The war left wounds that were slow to heal. The end of hostilities did allow de Valera step out from the shadows of the anti-Treaty IRA as the politician best equipped to translate opposition to the Free State into a coherent political message. Although Sinn Féin had been dormant for over twelve months, with just 19 local cumainn by the summer of 1923, the foundation of Cumann na nGaedheal provided the anti-Treatyites an opportunity to retain the evocative party label.[15]

De Valera reconstituted Sinn Féin as an anti-Treaty party pledged to abstain from the Free State Dáil. According to Michael Laffan this, ‘third Sinn Féin’, ignored the outgoing officer board and standing committee and therefore ‘broke the continuity between the post-rising and the post- civil war parties’.[16] In the August 1923 general election Cumann na nGaedheal won 65 seats to Sinn Féin’s 44. However, with Sinn Féin abstaining from the Dáil Cosgrave was secure in power.

Fianna Fáil’s foundation

In time, Sinn Féin’s abstention from the Dáil frustrated de Valera and like-minded colleagues Seán Lemass and Seán MacEntee. By remaining outside the Dáil Sinn Féin was failing to offer voters an alternative to Cumann na nGaedheal.[17]

Sinn Féin’s disagreement with Cumann na nGaedheal seemed rooted in the 1921-22 Treaty debate and the abstract ideal of ‘the Republic’. Most voters were more concerned with the bread-and-butter issues of the Free State, especially unemployment and housing, while abstention limited the capacity of the republicans to capitalise on Cumann na nGaedheal’s political difficulties.

In March 1925 the Irish Independent ridiculed Sinn Féin’s stance arguing that its only reply to the concerns of the unemployed and tenement dwellers was to ‘wait until the Republic is recognised’.[18]

Sinn Fein was reconstituted in 1923 as an anti-Treaty party. Eamon de Valera and most of his followers left it in 1926 to found Fianna Fail.

In March 1926 de Valera and his followers finally split from Sinn Féin over the question of abstentionism and announced that they would set up a new republican party. From its foundation, in Dublin’s La Scala Theatre on 16 May 1926, Fianna Fáil focussed on those bread-and-butter issues by developing a radical social and economic programme. The Boundary Commission debacle, in which Cosgrave was forced to accept the existing border, had, moreover, allowed Fianna Fáil to retrospectively frame its opposition to the Treaty around the issue of partition.[19]

In August 1927 de Valera led the party into the Dáil, taking the oath as an ‘empty formula’. Voters responded favourably as Fianna Fáil gained 9% and won 57 seats, to Cumann na nGaedheal’s 62, in the snap election that followed in September. In the post-wall street crash years, Fianna Fáil attracted further support as the party of self-sufficiency. In the February 1932 election Fianna Fáil won a resounding victory. The party secured 72 seats to Cumann na nGaedheal’s 57.

The peaceful transfer of power from Civil War victor to Civil War vanquished in March 1932– just nine years after the end of that conflict – was an act of great political maturity (at a time when Europe was increasingly dominated by dictators).[20]

However, political passions were aroused under the new government. Within weeks of coming to office, the Fianna Fáil government ‘drifted’ into a hardline Anglo-Irish policy which eventually led to the Economic War with Britain. De Valera’s policy of economic nationalism through retention of the ‘land annuities’, and efforts to unilaterally amend the Treaty settlement through the “Removal of Oath Bill”, resulted in British retaliation.

Duties were placed on Irish bacon, butter, cream, eggs, live animals, poultry and other meats. For Irish agriculture, ‘this affected £26m out of £36m of Irish exports to Britain’.[21] Cumann na nGaedheal supporters were further unnerved when the new government released IRA prisoners and removed a constitutional ban that had been placed on it by Cosgrave

From Cumann na nGaedheal to Fine Gael

Labour were the main casualties of the Fianna Fáil electoral advance, declining from 22 seats in June 1927 to just 7 seats in 1932. Fianna Fáil was growing its support by moving leftward whereas Cumann na nGaedheal had stagnated through consolidating the right.[22]

In truth, Cumann na nGaedheal had never succeeded in bringing the whole of the pro-Treaty vote under its wing. During the 1920s the Farmers’ Party challenged it in several rural constituencies while the brief existence of the National League, and the persistent success of independents, also attracted potential Cumann na nGaedheal voters. [23]

Although attempts to create a more formal alliance between Cosgrave’s party and the Farmers’ had failed in the 1920s, the prospects for an accommodation between Cumann na nGaedheal and those to its right had improved now that it was in opposition to a Fianna Fáil government that was engaged in an ‘Economic War’ with Britain.

Fine Gael was formed in 1933 as a response to Fianna Fail’s electoral victories and was a merged of Cumman na nGaedheal, the National Centre Party and the Blueshirts.

While commercial farmers saw their wealth dwindle, many small farmers were unaffected by the agricultural slump. As a direct result of the worsening situation, a new party was established to represent those farmers most adversely affected. In September 1932 the National Centre Party was launched under the leadership of Frank MacDermot and James Dillon.[24]

It was clear that this new party had the potential to cut across Cumann na nGaedheal’s existing support among farmers. As Cumann na nGaedheal struggled to adapt to life on the opposition benches, Cosgrave’s party gave him a mandate to negotiate a merger with the Centre Party.[25]

However, the move was scuppered when de Valera announced a snap general election. This election was to be one of the most bitter in the history of the state and many opposition meetings were disrupted by the IRA’s ‘no free speech for traitors’ campaign. As a consequence, a little-known organisation that had been established the previous autumn, the Army Comrades Association (ACA), emerged as the self-appointed protectors of both Cumann na nGaedheal and the Centre Party. Its ranks also swelled with disgruntled farmers. [26]

Another defeat to de Valera left Cumann na nGaedheal with just 48 seats as the Centre Party picked up 11 seats and 9% of the vote. Now in a stronger position, the Centre Party pushed for a genuine merger rather than their absorption by Cosgrave’s party.

By April 1933 the ACA had adopted the ‘Blue shirt’ uniform and in July it was rebranded as the National Guard under the leadership of dismissed Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy[27]. The nature of ‘Blueshirtism’, 1933-36 remains a subject of controversy and there is unlikely to ever be a consensus as to what it constituted. While its growth in 1933 was linked to the Economic War, O’Duffy and other leading members were admirers of continental fascism. Most Blueshirts appear to have been motivated by a mixture of Civil War legacies and the controversies of the early 1930s.[28]

Figures in both parties thought it would be useful to bring the Blueshirts into the merger process to add dynamism while the Centre Party were keen to dilute the appearance of a Cumann na nGaedheal takeover.

Although Blueshirt leader Eoin O’Duffy was reluctant to involve the organisation in party politics he eventually acquiesced when de Valera banned the National Guard on 22 August. To smooth the merger process O’Duffy was offered its presidency. Cosgrave would remain the Dáil leader of the new party.[29]

The United Ireland Party/Fine Gael was formally launched on 8 September 1933. In its manifesto, Fine Gael ‘explicitly committed itself to democracy’. However, the Blueshirts retained their autonomy from the overall party structure and this would prove an outlet for O’Duffy’s more extreme tendencies. O’Duffy’s erratic style – he was at odds with his own party’s support for a return to free trade – led to internal tensions. He subsequently resigned from the party on 18 September 1934 after attempts were made to censure his speeches.

In October 1936 Blueshirt director Ned Cronin was expelled from Fine Gael after resisting the party’s efforts to bring the organisation under the control of the party’s standing committee. Within a month, the affairs of the Blueshirts were wound down though the Blueshirts have remained ‘the skeleton in Fine Gael’s cupboard’, blemishing the party’s record.[30].

Fianna Fáil, meanwhile, focussed on implementing its policy of protectionism which was more in keeping with the trend of economics in the 1930s.[31] and presented itself as a constitutional vehicle for republicanism in contrast to an IRA from which it had become estranged by the mid- 1930s. In June 1936 de Valera’s government reinstated Cosgrave’s ban on the IRA. Fianna Fáil was now the party of government in much the same way that Cumann na nGaedheal had been in the 1920s.

Mid-Century evolution

In broad terms, Fine Gael has been slightly to the right of Fianna Fáil for most of its history. However, lengthy periods of uninterrupted Fianna Fáil government during the twentieth-century blunted the radical edge of de Valera’s party.

In broad terms, Fine Gael has been slightly to the right of Fianna Fáil for most of its history. However, lengthy periods of uninterrupted Fianna Fáil government during the twentieth-century blunted the radical edge of de Valera’s party.

Towards the end of its first (of two) sixteen-year stints as a single party government Fianna Fáil had lost its early radicalism. This is exemplified by the fall out from the teacher’s strike and the emergence of Clann na Poblachta in the late 1940s.[32]

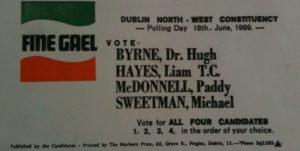

As Mary Daly has observed, moreover, the fact at all four general elections held between 1948 and 1957 resulted in a change of government ‘challenges the belief that party allegiance was fossilised on the basis of civil war divisions’. Although Fine Gael recorded its highest shares of the vote since the 1930s in the elections of 1965 and 1969 it remained in opposition.[33] Labour remained opposed to coalition during the 1960s, hoping instead to differentiate itself from the two main parties by rebranding as socialist.

With no realistic prospect that Fine Gael could win an overall majority a second sixteen-year period of consecutive Fianna Fáil government followed between 1957-1973.

Traditionally Fianna Fail was to the left of Fine Gael but in the 1960s, Fianna Fail became more of a pro-business party while some sections of Fine Gel began to identify themselves as ‘social democrats’.

As is normal in any party system, different leaders have put their own stamp on each of the two main parties. When Lemass succeeded de Valera as Fianna Fáil leader and Taoiseach in 1959 he brought the party in a new direction, further to the political right. Fianna Fáil abandoned the policy of economic self-sufficiency and became a party of free enterprise and encouraging foreign investment in a way that it had not been up to that point.

At this time, Fianna Fáil also attracted the support of Irish business as exemplified in the formation of Taca to raise funds from the entrepreneurial classes.[34] In July 1961 the Lemass government formally applied to join the European Economic Community (EEC). Ireland finally joined the EEC, along with Britain and Denmark, on 1 January 1973. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael both endorsed the ‘yes’ campaign in the 1972 referendum and each party has embraced pro-Europeanism, with Fine Gael joining the broadly Christian Democrat European People’s Party.[35]

In 1965 Fine Gael’s new generation of leaders responded to Lemass’s successes, by moving to the left of Fianna Fáil with the adoption of the Just Society manifesto. This was a radical departure in Irish politics and committed a future Fine Gael government to a policy of full-scale economic planning and better public services.[36]

In the 1966 Presidential election the Fine Gael moderniser Tom O’Higgins came within one percentage point, and 10,000 votes, of defeating incumbent Eamon de Valera.[37] At the 1968 Fine Gael Ard Fheis there was strong support from the Fine Gael grassroots for a move to change the party’s name to ‘Fine Gael -Social Democrat Party’ but this was scuppered by the chair Gerard Sweetman who urged the conference to refer the matter to a postal ballot of branches where it was defeated.[38]

Conclusion

After the Civil War, Sinn Féin’s successor parties evolved their own distinct identities and cultures. They succeeded in normalising politics within a democratic framework during a turbulent period in Irish and European history and they have both reflected the nature of Irish society. After leading the first Inter-Party Government in 1948 Fine Gael was able to reinvent itself as a party that could lead an alternative coalition government while Fianna Fáil made that same adjustment in 1989.

People tend to examine Irish politics with reference to British politics because we consume so much UK media. However, given Ireland’s system of proportional representation and coalition government, Europe provides a much better comparison.[39]

Neither Fianna Fáil nor Fine Gael can be characterised as either Labour or Conservative parties

Neither Fianna Fáil nor Fine Gael can be characterised as either Labour or Conservative parties. Rather nationalism, republicanism, Christian democracy, social democracy and, in more recent decades, pro-Europeanism are all in the mix when you look into the DNA of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.

The British system of first past the post has led to a system in which two, clear blocs dominate within a quite polarised setting. Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil are a product of a proportional representation electoral system in which compromise and coalitions are fundamental. In recent decades Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil have offered themselves to the electorate as parties that can lead coalitions of either the centre-left or centre-right.[40]

The results of the 2020 election have transformed the landscape and raise questions about the future of the two parties that have dominated the politics of the Irish state. Perhaps developments in Germany over the past 15 years, where the Christian Democrats (CDU) and Social Democrats (SPD) have regularly served in coalition, may point to the shape of things to come if Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are to retain their separate identities in a changing political landscape.

No doubt we will hear plenty more analysis of ‘Civil War politics’ but we should not discount that these two parties are separated by almost 100 years of history.

Dr Mel Farrell is the author of Party Politics in a New Democracy: the Irish Free State, 1922-37 (Palgrave, 2017). He has taught history in DCU, Maynooth University and UCD.

References

[1] Michael Laffan, The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916-1923 (Cambridge, 1999), pp 116-121, pp 346-350.

[2] Mel Farrell, Party Politics in a New Democracy: the Irish Free State, 1922-37 (Basingstoke, 2017), pp 73-76.

[3] See, for example, https://www.thejournal.ie/fine-gael-fianna-fail-manifestos-4978208-Jan2020/ [accessed 13 May 2020].

[4] David Fitzpatrick, Politics and Irish Life, 1913-1921 (Cork, 1998 edn.), pp 134-137.

[5] John M. Regan, The Irish Counter-Revolution, 1921-1936: Treatyite politics and settlement in independent Ireland (Dublin, 2001 edn.), p. 22.

[6] For further reading, Mícheál Ó Fathartaigh and Liam Weeks (eds), The Treaty: Debating and Establishing the Irish State (Dublin, 2018).

[7] Michael Laffan, Judging W.T. Cosgrave: the foundation of the Irish state (Dublin, 2014), p. 104

[8] Laffan, Resurrection of Ireland, pp 372-373.

[9] See Michael Hopkinson, Green against Green: The Irish Civil War (Dublin, 2004 edn.), pp 62-65, pp 70-73.

[10] Laffan, Judging Cosgrave, p. 116.

[11] Hopkinson, Green against Green, p. 70.

[12] See John Dorney, ‘Today in Irish History- Assassination of Sean Hales, December 7 1922’: https://www.theirishstory.com/2010/12/07/today-in-irish-history-december-7-1922-the-assassination-of-sean-hales/#.Xr__NGhKg2w [accessed 14 May 2020].

[13] Hopkinson, Green against Green, pp 190-191.

[14] Mulcahy diary, 21 Dec. 1922 (UCDA, Mulcahy papers, P7/B/325). See also Laffan, Resurrection of Ireland, pp 431-422.

[15] Eamon de Valera to the organising committee, 6 June 1923 (NAI, Cumann na Poblachta & Sinn Féin papers, 1094/1/13).

[16] Laffan, Resurrection of Ireland, p. 436. This was also the judgment of the 1948 ‘Sinn Féin funds case’ that went before the courts.

[17] Richard Dunphy, The Making of Fianna Fáil power in Ireland, 1923-1948 (New York, 1995), pp 66-70.

[18] Irish Independent, 2 March 1925.

[19] John Bowman, De Valera and the Ulster Question, 1917-1973 (Oxford, 1989), p. 94.

[20] Farrell, Party Politics, p. 249.

[21] Dermot Keogh, Twentieth-Century Ireland: Revolution and State building (Dublin, 2005 edn), p. 69, p. 78.

[22] Farrell, Party Politics, p. 182.

[23] Ciara Meehan, The Cosgrave Party: a history of Cumann na nGaedheal, 1923-33 (Dublin, 2010), p. 87.

[24] Maurice Manning, The Blueshirts (Dublin, 2006 edn.) p. 43.

[25] Special meeting of the Cumann na nGaedheal standing committee and parliamentary party, 3 January 1933 (UCDA, Cumann na nGaedheal papers, P39/min/3).

[26] Regan, Counter Revolution, p. 327; Manning, Blueshirts, p. 105

[27] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy: a self-made hero (Oxford, 2005), p. 205.

[28] Mel Farrell, ‘From Cumann na nGaedheal to Fine Gael: the foundation of the United Ireland Party in September 1933’, Éire-Ireland, vol. 18, no. 3 (Autumn 2014), pp 143-171.

[29] Meehan, Cosgrave Party, p. 220.

[30] McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy, p. 269.

[31] Donnacha Ó Beacháin, Destiny of the Soldiers: Fianna Fáil, Irish Republicanism and the IRA, 1926-73 (Dublin, 2010), p. 122.

[32] Keogh, Twentieth-Century Ireland, pp 171-173, pp 179-182.

[33] Mary E Daly, Sixties Ireland: Reshaping the economy, state and society, 1957-1973 (Cambridge, 2016), pp 257-258. See, also, Michael Gallagher, The Irish Labour party in transition, 1957-82 (Manchester, 1982), pp 55-63.

[34] Keogh, Twentieth-Century Ireland, pp 278-279

[35] Daly, Sixties Ireland, p. 25; Keogh, Twentieth-Century Ireland, p. 327.

[36] See Ciara Meehan, A Just Society for Ireland?, 1964-1987 (Basingstoke, 2013).

[37] Daly, Sixties Ireland, p. 267.

[38] Michael Gallagher and Michael Marsh, Days of Blue Loyalty: the politics of membership of the Fine Gael party (Dublin, 2002), p. 28. See also Stephen Collins, The Cosgrave Legacy (Dublin, 1996), p. 94.

[39] Tony Judt, Postwar: a history of Europe since 1945 (London, 2010 edn.) p. 7, pp 157-158.

[40] See Irish Times analysis of the 1997 general election, 9 June 1997.